The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The beautiful Io moth, Automeris io (Fabricius), is one of our most recognizable moths. It is distinctive because of its prominent hind wing eyespots. The Io moth, like many of the other saturniid moths, is less common now in parts of its range. With the exception of Cape Cod and some of the Massachusetts islands, it is now rare in New England where it was once common, and its populations have declined in the Gulf States (with the exception of Louisiana) since the 1970s (Manley 1993). The attractive Io moth caterpillar is also well-known because of its painful sting.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Automeris is a large genus with about 145 species (Heppner 1996). All Automeris species are characterized by large eyespots in the middle of the hind wings. Most species are found in Central and South America. There are seven species in the United States. Five of these, Automeris zephyria Grote (New Mexico and western Texas), Automeris cecrops (Boisduval), Automeris iris (Walker), Automeris patagoniensis Lemaire, and Automeris randa Druce (southeastern Arizona) are found only in the western U.S. (Powell & Opler 2009). Automeris louisiana is found only in coastal salt marshes of southwestern Mississippi, Louisiana, and eastern Texas where it feeds predominately (if not exclusively) on smooth cordgrass, Spartina alterniflora Loisel (Tuskes et al. 1996).

Synonymy

Fabricius (1775, p.560) described the Io moth and named it Bombyx io. Abbott and Smith (1797, p.97) published the first account of the Io moth's life cycle under the name Phalaena io. Some early references used the genus name Hyperchiria (e.g., Eliot & Soule 1902, Lintner 1872, Stratton-Porter 1921, Strecker 1872).

Strecker (1872, p.139) described Hyperchiria lilith as a new species based on a series of females from Georgia with more reddish colored forewings (Figure 2). Populations of this color variant are common in the deep Southeast including Florida, and the name "lilith" is still in common usage as a subspecies of Automeris io to designate females with this phenotype and males that have orange-brown forewings. However, Tuskes et al. (1996) stated that the lilith phenotype occurs over a broad geographic range (as far north as New York) and "does not have a distribution pattern consistent with the subspecies concept." For this reason and the fact that female forewing coloration of lilith specimens is so inconsistent, they synonymized lilith with nominate io.

Credit: Strecker (1872, Plate XV, Fig. 17)

For a more complete list of synonyms for Automeris io, see Ferguson (1972) or Heppner (2003).

Less familiar common names for the Io moth include corn emperor moth (Abbott & Smith 1797) and peacock moth.

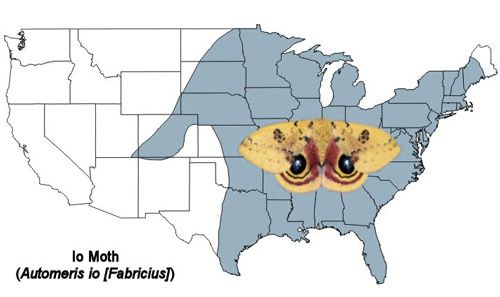

Distribution

The Io moth is found from southern Canada throughout the eastern U.S. and to eastern Mexico (Tuskes et al. 1996).

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida. (Based on map from Tuskes et al. 1996)

Description

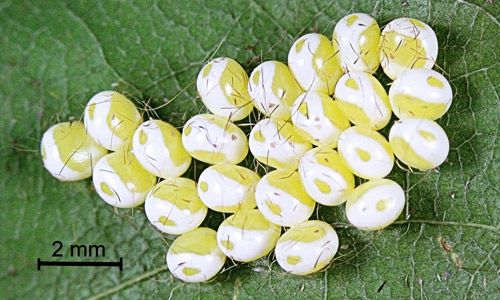

Eggs

Eggs measure approximately 1.7 × 1.3 × 1.1 mm (Peterson 1965). They are white with yellow transverse areas on the sides and a yellow spot on the top of each egg that surrounds the micropyle (opening through which sperm enters). After three to five days, the micropyle turns black in fertilized eggs (Tuskes et al. 1996) but remains yellow in unfertilized eggs (Villiard 1975). As the eggs mature, the lateral yellow areas become orange or brown.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

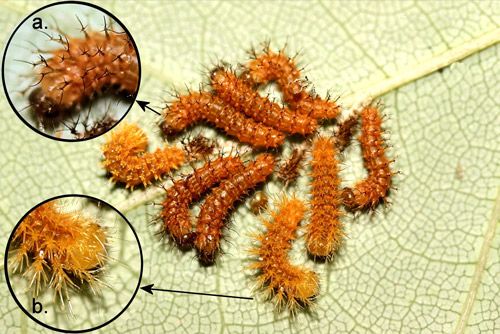

Larvae

Tuskes et al. (1996) stated that all saturniids have five larval instars. However, the number of instars may vary depending on rearing conditions. When reared on sub-optimal hosts, larvae may undergo extra molts. Sourakov (2013) found that Io moth caterpillars reared on coral bean (Erythrina herbacea Linnaeus) required seven instars to complete their larval development.

First instar Io moth larvae are reddish-brown with six longitudinal light lines and six longitudinal rows of spine-bearing scoli (Packard 1914; Pease 1961). Instars 2-4 become increasingly more yellowish-brown and the longitudinal lines become more distinct and lighter in color.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Full-grown (usually fifth instar) larvae are approximately 60 mm (about 2 1/3 in.) in length (Godfrey et al. 1987). They are green with a lateral abdominal white stripe edged on the top and bottom with red stripes. Both thoracic legs and abdominal prolegs are reddish, and there are ventro-lateral reddish patches on the abdominal segments. The body is virtually surrounded with scoli bearing black-tipped venomous spines.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida. For detailed descriptions of the larval instars see Lintner (1872), Packard (1914) and Pease (1961).

Cocoons

Cocoons are thin and papery.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

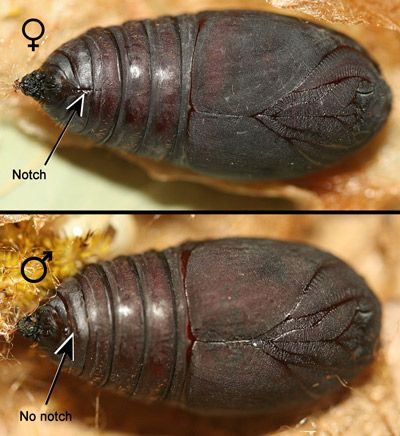

Pupae

Pupae are dark brown. Female pupae have longitudinal notches (the developing female gonopores) on the ventral aspect of the fourth and fifth abdominal segments behind the segment that is partially covered by the developing wings (Figure 16, top).

In male pupae, the posterior margin of the fourth abdominal segment behind the segment that is partially covered by the developing wings is entire (arrow), and the notches are lacking. The fifth abdominal segment behind the segment that is partially covered by the developing wings bears two short tubercles (the developing male gonopores) (Figure 16, bottom).

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida. For detailed descriptions of the pupae, see Mosher (1914 & 1916)

Adults

Io moths have wingspans of 50-80 mm (approx. 2-3 in.) (Beadle & Leckie 2012; Covell 2005). Females are larger than males. Male and female Io moths can be differentiated by the antennae (Figure 17). The antennae of males are quadripectinate. Female antennae are described as bipectinate (Powell & Opler 2009) or bidentate (Ferguson 1972). Without magnification, female antennae appear almost thread-like.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

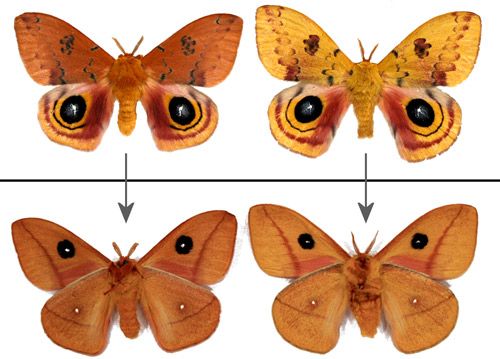

Female forewings vary from red to brown (Figures 18 and 25).

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Male forewings vary from yellow to tawny or orange-brown. The yellow phenotype is predominant in males from more northern areas. Darker male forewings are more common in southern populations and the darker coloration is often characteristic of males from diapausing pupae (Manley 1990[1991] & 1993; Sourakov 2014).

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

For photographs showing more of the color variation of adult Io moths, see Ferguson (1972) and Sourakov (2014). Manley (1990 [1991]) has conducted extensive studies on the genetics of some of the color and pattern variations in Io moths. Also, both bilateral (Hessel 1964) and mosaic (Manley 1971) gynandromorphs and an aberrant male in which the hind wings are mostly covered with black (Covell 2012) have been reported.

Life Cycle

Adults usually emerge in late morning or early afternoon and remain still until evening. Collins and Weast (1961) reported that females begin to release a pheromone to call males from approximately 9:30 pm to midnight on the day of emergence. However, Manley (1993) stated that copulation rarely occurs on the night of emergence. Adults do not feed and are short-lived.

Eggs are laid in clusters on leaves or stems (usually on the undersides of leaves) over the next several nights (Peterson 1965; Tuskes et al. 1996). Eggs usually hatch within 8-11 days. Soon after hatching from the eggs, larvae eat the eggshells (chorions) (Figure 20) before beginning to feed on the host plant.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Early instar larvae are gregarious and march in lines following silk trails as they move to new feeding areas (Soule 1891) (Figures 21 and 22).

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

When ready to molt, early instar larvae queue into rosettes with the heads facing outwards (Russi et al. 1973) (see Figure 7 above). After the hardening of their new exoskeletons, recently molted larvae return and eat their exuviae except for the head capsules.

When fully grown, larvae crawl down from the host plants and spin cocoons in leaf litter or in protected places like crevices in logs or rocks (Tuskes et al. 1996).

Manley (1993) conducted detailed studies of diapause and reported that northern populations are univoltine (one generation per year), those from coastal South Carolina, the Gulf States, and north Florida are probably bivoltine, those from Orlando, Florida south to a line intersecting Bradenton-Sebring-Fort Pierce probably have four generations, and more southerly Florida populations probably have four or five non-diapausing generations. Sourakov (2014) studied Io moths from the Gainesville, Florida area and suggested that there may be plasticity in voltinism based on genetics and environmental conditions.

Host Plants

Io larvae are polyphagous. The following list of genera of the most common host plants for Io moths was compiled from Beadle & Leckie (2012), Collins & Weast (1961), Covell (2005), Ferguson (1972), Tuskes et al. (1996), and Wagner (2005).

Although Io moth larvae are polyphagous, they may have regional host preferences (Tuskes et al. 1996). For example, Collins and Weast (1961) mention that mesquite (Prosopis spp.) is a preferred host along the Texas Gulf Coast and Minno (personal communication) and Tuskes et al. (1996) list the following plants as common hosts in South Florida and the Florida Keys:

Apparently, not all plants utilized by Io moths are equally suitable for larval development (Sourakov 2013).

For more complete lists of recorded hosts, see Heppner (2003), Robinson et al. (undated), and Tietz (1972). Scientific names, common names, family names and distribution maps for the host plants can be found in the Plants Database - USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (2014).

Natural Enemies

Predators

The Io moth probably has a variety of predators during its life cycle including birds, mammals, spiders, and insects. Tuskes et al. (1996) reported that hornets commonly attack Io moth larvae.

Parasitoids

At least seven species of tachinid flies (Diptera: Tachinidae) (Arnaud 1978, O'Hara 2013, Peigler 1994 [1996]), two species of ichneumonids (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) and two species of braconids (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) (Krombein et al. 1979, Peigler 1994 [1996]) have been reported from Automeris io.

Tachinid parasitoids of Automeris io

Compsilura concinnata (Meigen)

Chetogena (formerly Euphorocera) claripennis (Macquart)

Carcelia formosa (Aldrich & Webber)

Sisyropa eudryae (Townsend)

Nilea (formerly Lespesia) dimmocki (Webber)

Lespesia frenchii (Willliston)

Lespesia sabroskyi Beneway

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Ichneumonid parasitoids of Automeris io

Hyposoter fugitivus (Say)

Enicospilus americanus (Christ)

Braconid parasitoids of Automeris io

Cotesia electrae (Viereck)

Cotesia hemileucae (Riley)

Defenses

Caterpillars of all instars sting (Eliot & Soule 1902) and probably gain some protection from vertebrates. The contrasting white and red lateral stripes of fifth instar larvae are likely aposematic. The spines may also repel some insect predators. Murphy et al. (2010) found that reduviid bugs and Polistes wasps were less likely to attack heavily spined limacodid larvae than weakly spined ones.

Adults are strictly nocturnal (Fullard & Napoleone 2001). They remain motionless during the daytime and mimic the dead brown, red, and yellow leaves that are common in forests. Dead leaves of a number of plant species exhibit a range of colors that match the color variants of male and female Io moths in their typical resting positions (Figure 24). Many of the leaves have mottled patterns that enhance the mimicry of the moths.

The relatively low density of Io moth populations (Tuskes et al. 1996) combined with the highly variable patterns in the moths' wings may prevent vertebrate predators from forming search images.

![Figure 24 Figure 24. Io moth, Automeris io (Fabricius) - image of adult female digitally pasted into photo with dead Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia [Linnaeus]) leaflets (top); image of adult male digitally pasted into photo with dead flowering dogwood (Cornus florida Linnaeus) leaves (bottom).](/image/IN1065/Db68ujdyd2/Dywt64hdvu/Dywt64hdvu-2048.webp)

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

When threatened, adults flip the forewings forward exposing the large eyespots on the hind wings (Figure 24). The eyespots have white highlights resembling the glint (reflections) of vertebrate eyes. Large eyespots in butterflies have been shown to startle predatory birds (Blest 1957).

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Medical Importance

Incidence and Symptoms

Stings to humans by Io moth caterpillars are not particularly common. Of 112 cases of caterpillar stings in Louisiana, 11% were attributed to Io moth caterpillars (Everson et al. 1990). However, stings are certain to be underreported.

In laboratory experiments, human volunteers varied in their sensitivity to Io caterpillar stings, and a rabbit, hamster, and mouse failed to react to the stings (Hughes & Rosen 1980).

Stings commonly result in a nearly immediate painful nettling and pruritic (itching) reaction followed by formation of a localized wheal (welt) and erythematous (reddened) flare around the wheal. The pain usually resolves within a couple of hours and the wheal and flair within 6-8 hours (Diaz 2005, Hossler 2009 & 2010, Hossler et al. 2008, Hughes & Rosen 1980, Rosen 1990). Systemic symptoms are rare.

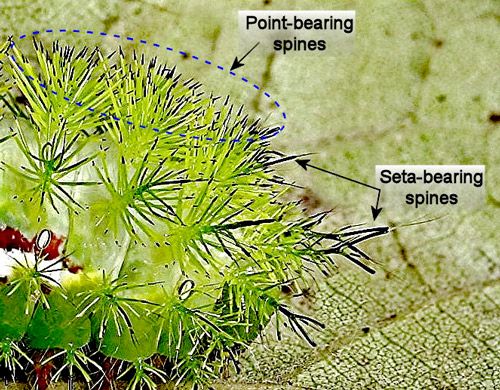

Venomous Spines

Virtually the entire bodies of larvae are protected by venomous spines. The spines have been described in detail by Battisti et al. (2011) and Gilmer (1925). Some spines are tipped with points and others with setae (Gilmer 1925) (Figure 26). The functional difference, if any, between point-tipped and seta-tipped spines is unknown.

When spines penetrate the skin, the tips break off and release the venom. Spine tips may remain in the skin causing further irritation (Hossler et al. 2008). Battisti et al. (2011) hypothesized that as embedded spine tips begin to break down in the skin, the chitin may invoke an inflammatory response. Chitin particles of about 10-40 µm in size are known to invoke pro-inflammatory immune responses, but smaller chitin particles may actually be anti-inflammatory (Alvarez 2014, Da Silva et al. 2009). The points on Io moth caterpillar spines that are likely to remain in the skin are roughly 12 µm in length - right at the threshold of the inflammatory size. However, their irritating effect may be merely mechanical or due to small amounts of venom remaining in the points.

Credit: Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Treatment

Recommended treatments include application and removal of cellophane tape to the affected area to strip embedded tips of the urticating spines from the skin. Ice packs should be applied to the affected area to minimize the inflammatory response (Diaz 2005; Hossler et al. 2008).

Venom

Io moth caterpillar venom has not been characterized (Diaz 2005), but it is unlikely to contain histamine or involve histamine-mediated reactions. Intradermal injections of the anti-histamine diphenhydramine-HCl (Benadryl®) at the site of stings in human volunteers failed to block reactions (Hughes & Rosen 1980).

Caterpillar venoms, in general, have not been well-studied. Because of the large, relatively accessible poison glands of Io moth caterpillars, Goldman et al. (1960) recommended studies with Io moth caterpillar venom as a model to determine the chemicals responsible for the pruritic symptoms of caterpillar stings. Eisner et al. (2005, p. 295) stated, "There is no reason why caterpillar venoms should not turn out to contain novel toxins of interest."

Rearing

Io moth larvae are relatively easy to rear. Although they will tolerate more crowding than most other saturniid larvae, overcrowding and high humidity may increase risk of disease (Tuskes et al. 1996). Villiard (1975) listed wild cherry as the preferred host. Tuskes et al. (1996) recommended presenting early instar larvae with a variety of food choices to determine their preference. All Io specimens pictured here were either collected as larvae on redbud (Cercis canadensis Linnaeus) or reared on redbud from eggs of wild-collected females.

Prepupal larvae should be removed and provided with leaf litter or tissue paper as a medium for spinning their cocoons (Tuskes et al. 1996). After the pupae have hardened (approximately 7-10 days), the cocoons can be removed and placed into emergence cages. Although the cocoons may tear when handled, successful emergence of adults will not be affected. Diapause pupae may require a chilling period prior to emergence.

Wild-caught females have often already mated. Reared adults mate readily in small cages, or females may be tethered outside to attract wild males. Worth (1980) has designed a tether for large moths that also should work with Io moths.

Mythology

The specific epithet "io" is from the mythological Greek woman Io, who was first priestess of Hera, wife of Zeus the god of thunder and lightning and king of both gods and men.

Even the synonym "lilith" coined by Strecker (1872) has a mythological origin. According to Jewish mythology, Adam had two wives — the first wife (unnamed) from the Old Testament scripture Genesis 1:26-27. About 800-900 B.C., this mythical first wife became known as Lilith. She and Adam supposedly had a tumultuous relationship, and Lilith left Adam and according to some legends became a night monster or evil woman who killed babies. God then created a second wife from Adam's rib (Genesis 2:22) whom Adam named Eve (Genesis 3:20). The historical origin of the character Lilith is a matter of speculation. See Pelaia (2014) for a discussion of the Lilith myth.

The well-known early twentieth century naturalist Gene Stratton-Porter (1921) called the Io moth "Hera of the Corn" (literally goddess or queen of the corn) - in reference to the Greek goddess Hera mentioned previously and the fact that corn is an occasional host plant for Io moth larvae in central Indiana where she (Stratton-Porter) lived. In fact, children (including the author) were occasionally stung by Io moth caterpillars while playing hide-and-seek in the corn fields of the Midwest.

Control

Although Io moth caterpillars have been reported from cotton (Packard 1914) and corn (Abbot & Smith 1797, Stratton-Porter 1921), they are not sufficiently abundant to require control on these crops. Control would only be required if they present a stinging hazard in landscape plants.

If control measures are required, Bacillus thuringiensis applications or chemical insecticides recommended for control of other caterpillars should be effective. For current control recommendations, contact your County Extension office.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge Marc Minno for reviewing this article and offering helpful suggestions.

Selected References

Abbott J, Smith JE. 1797. Natural History of the Rarer Lepidopterous Insects of Georgia. Vol. 1. Bensley, London. 100 pp.

Alvarez FJ. 2014. The effect of chitin size, shape, source and purification method on immune recognition. Molecules 19(4): 4433-4451.

Arnaud PH. 1978. A Host-Parasite Catalog of North American Tachinidae (Diptera). United States Department of Agriculture Miscellaneous Publication 1319. Washington, D.C.

Battisti A, Holm G, Fagrell B, Larsson S. 2011. Urticating hairs in arthropods: their nature and medical significance. Annual Review of Entomology 56: 203-220.

Beadle D, Leckie S. 2012. Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America. Houghton Mifflin. New York, N. Y. 611 pp.

Blest AD. 1957. The function of eyespot patterns in the Lepidoptera. Behaviour 11(2/3): 209-255.

Collins MM, Weast RD. 1961. Wild Silkmoths of the United States: Saturniinae. Experimental Studies and Observations of Natural Living Habits and Relationships. 1961. Collins Radio Company. Cedar Rapids, Iowa. 138 pp.

Covell CV. 2005. A Field Guide to Moths of Eastern North America. Special Publication Number 12. Virginia Museum of Natural History. Martinsville, Virginia. 496 pp.

Covell CV. 2012. A striking aberrant Automeris io. Association for Tropical Lepidoptera Notes. p. 4. Gainesville, Florida.

Da Silva CA, Chalouni C, Williams A, Hartl D, Lee CG, Elias JA. 2009. Chitin is a size-dependent regulator of macrophage TNF and IL-10 production. Journal of Immunology 182(6): 3573-3582.

Diaz JH. 2005. The evolving global epidemiology, syndromic classification, management, and prevention of caterpillar envenoming. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 72(3): 347-357.

Eisner T, Eisner M, Siegler M. 2005. Chapter 63. Class Insecta, Order Lepidoptera, Family Saturniidae, Automeris io, the Io moth. pp. 292-296. In: Secret Weapons: Defenses of Insects, Spiders, Scorpions, and Other Many-legged Creatures. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 372 pp.

Eliot IM, Soule CG. 1902. Caterpillars and their Moths. Century. New York. 302 pp.

Everson GW, Chapin JB, Normann SA. 1990. Caterpillar envenomations: a prospective study of 112 cases. Veterinary and Human Toxicology 32: 114-119.

Fabricius IC. 1775. Systema Entomologiae. Officina Libraria Kortii. Flensburgi et Lipsiae. 832 pp.

Ferguson DC. 1972. The Moths of North America. Fascicle 20.2B. Bombycoidea. Saturniidae (Part). Classey. Hampton, England. pp. 157-162.

Fullard JH, Napoleone N. 2001. Diel flight periodicity and the evolution of auditory defenses in the Macrolepidoptera. Animal Behaviour 62(2): 349-368.

Gilmer PM. 1925. A comparative study of the poison apparatus of certain lepidopterous larvae. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 18: 203-239.

Godfrey GL, Jeffords M, Appleby JE. 1987. Saturniidae (Bombycoidea). In Stehr FW. (ed.). Immature Insects. Kendall/Hunt. Dubuque, Iowa. pp. 513-521.

Goldman L, Sawyer F, Levine A, Goldman J, Goldman S, Spinanger J. 1960. Investigative studies of skin irritations from caterpillars. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 34(1): 67-79.

Heppner JB, (ed.). 1996. Automeris. pp. 36-39. In: Atlas of Neotropical Lepidoptera. Checklist: Part 4b. Drepanoidea - Bombycoidea - Sphingoidea. Association for Tropical Lepidopera & Scientific Publishers Gainesville, FL. 87 pp.

Heppner JB. 2003. Lepidoptera of Florida. Part 1. Introduction and Catalog. Volume 17 of Arthropods of Florida and Neighboring Land Areas. Division of Plant Industry. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Gainesville, Florida. 670 pp.

Hessel SA. 1964. A bilateral gynandromorph of Automeris io (Saturniidae) taken at mercury vapor light in Connecticut. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 18: 27-31.

Hossler EW. 2009. Caterpillars and moths. Dermatologic Therapy 22: 353-366.

Hossler EW. 2010. Caterpillars and moths. Part II. Dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 62: 13-28.

Hossler EW, Elston DM, Wagner DL. 2008. What's eating you? Io moth (Automeris io). Cutis 82: 21-24.

Hughes G, Rosen T. 1980. Automeris io (caterpillar) dermatitis. Cutis 26: 71-73.

Krombein KV, Hurd Jr. PD, Smith DR, Burks BD. 1979. Catalog of Hymenoptera in America North of Mexico. Volume 1. Symphyta and Apocrita (Parasitica). Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. 1198 pp.

Lintner JA. 1872. Transformations of Hyperchiria io (Fabricius). From the twenty-third annual report of the New York State Cabinet of Natural History. Appendix E. Entomological Contributions of J.A. Lintner. Weed, Parsons. Albany, N.Y. pp. 146-148.

Manley TR. 1971. Two mosaic gynandromorphs of Automeris io (Saturniidae). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 25: 234-238.

Manley TR. 1990(1991). Heritable color variants in Automeris io (Saturniidae). Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 29(1-2): 37-53.

Manley TR. 1993. Diapause, voltinism, and foodplants of Automeris io (Saturniidae) in the southeastern United States. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 47(4): 303-321.

Mosher E. 1914. The classification of the pupae of the Ceratocampidae and Hemileucidae. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 7(4): 277-300.

Mosher E. 1916. A classification of the Lepidoptera based on characters of the pupae. Bulletin of the Illinois State Laboratory of Natural History 12:17-159.

Murphy SM, Leahy SM, Williams LS, Lill JT. 2010. Stinging spines protect slug caterpillars (Limacodidae) from multiple generalist predators. Behavioral Ecology 21: 153-160.

O'Hara JE. 2013. Taxonomic and host catalogue of the Tachinidae of America north of Mexico. (Last update: 10 December 2013)

Packard AS. 1914. Monograph of the Bombycine Moths of North America, Including Their Transformations and Origin of the Larval Markings and Armature. Part 3. Families Ceratocampidae, (exclusive of Ceratocampinae), Saturniidae, Hemileucidae, and Brahmeidae. Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences Volume 12. 515 pp. + 113 plates.

Pease RW. 1961. A study of first instar larvae of the Saturniidae, with special reference to Nearctic genera. Journal of the Lepidopterist's Society 14: 89-111.

Peigler RS. 1994 (1996). Catalog of parasitoids of Saturniidae of the world. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 33: 1-121.

Pelaia A. 2014. Where does the legend of Lilith come from? http://judaism.about.com/od/jewishculture/a/Where-Does-The-Legend-Of-Lilith-Come-From.htm

Peterson A. 1965. Some eggs of moths among the Sphingidae, Saturniidae, and Citheroniidae (Lepidoptera). Florida Entomologist 48: 213-219.

Plants Database. 2014. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. http://plants.usda.gov/java/

Powell JA, Opler PA. 2009. Moths of Western North America. University of California Press. Berkeley, California. 369 pp.

Robinson GS, Ackery PR, Kitching IJ, Beccaloni GW, Hernández LM. HOSTS - a Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants. (17 September 2014)

Rosen T. 1990. Caterpillar dermatitis. Dermatological Clinics 8(2): 245-252.

Russi K, Friedl F, Russi H. 1973. Queuing and rosette molting in Automeris io (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). Entomological News 84(2): 33-36.

Sourakov A. 2013. Larvae of io moth, Automeris io, on the coral bean, Erythrina herbacea, in Florida — the limits of polyphagy. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 67(4): 291-298.

Sourakov A. 2014. On the polymorphism and polyphenism of Automeris io (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) in North Florida. Tropical Lepidoptera Research 24(1): 52-58.

Soule CG. 1891. The march of Hyperchiria io. Psyche 6: 15.

Stratton-Porter G. 1921. Moths of the Limberlost. Doubleday, Page. Garden City, New Jersey. 369 pp.

Strecker H. 1872. Lepidoptera, Rhopaloceres and Heteroceres, Indigenous and Exotic; with Descriptions and Colored Illustrations. Owen's Steam Book & Job Printing Office. Reading, Pennsylvania. 143 pp.

Tietz HM. 1972. An Index to the Described Life Histories, Early Stages and Hosts of the Macrolepidoptera of the Continental United States and Canada. Part 1. The Allyn Museum of Entomology. Sarasota, Florida. (Distributed by Entomological Reprint Specialists. Los Angeles, California). 536 pp.

Tuskes PM, Tuttle JP, Collins MM. 1996. The Wild Silk Moths of North America. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, New York. 250 pp.

Villiard P. 1975. Moths and How to Rear Them. Dover. New York, New York. 242 pp.

Wagner DL. 2005. Caterpillars of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. 512 pp.

Worth CB. 1980. An elegant harness for tethering large moths. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 34(1): 61-63.