The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Tiger beetles occur on most continents. In the United States they are predominantly found in sandy open habitats, including river sandbars, ocean beaches, mudflats, dunes, rocky outcroppings, and even along woodland paths. As their name implies these are active, agile insects, quick to take flight, possessing good vision, and in many cases, having colorful patterns that are quite attractive. These are the "butterflies" of the beetle world. Many collectors readily acquire most species in a relatively short period of time. An entire journal (Cicindela) is devoted to the dissemination of collecting notes, systematics, and behavior of tiger beetles.

There are approximately 100 species of tiger beetles in the U.S., included in four genera: Amblycheila, Omus, Megacephala, and Cicindela. Two genera of tiger beetles occur in Florida (Megacephala and Cicindela). Within these genera, three named forms occur in Megacephala and the remaining 20+ occur in Cicindela.

Until recently, tiger beetles were placed in their own family, Cicindelidae. However, now they are considered to be gound beetles, family Carabidae.

Distribution

Shown below are several species of tiger beetles. All but one of these occur in Florida (C. splendida occurs in northern Georgia and the Appalachian Mountains and is not yet recorded from Florida). All photographs were taken in the habitat where they occurred.

Megacephala carolina floridana

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Megacephala carolina floridana—the taxonomy of this form and those of the carolina species complex is unresolved. This form occurs in the Florida Keys, and sporadically along the west coast of Florida as far north as Dixie County, always in salt marsh, mud flat habitats. It lacks the violet coloration of typical carolina and is probably the same as M. chevrolati which is known from the Yucatan peninsula.

Cicindela dorsalis media

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Cicindela dorsalis media occurs along the east coast of Florida on undisturbed beaches and along tidal flats. Adults are attracted to light. Larvae occur at the high tide line, a feature which has resulted in the demise of this species from many Florida beaches where pedestrian and vehicular traffic occur. Gulf coast populations are C. dorsalis saulcyi.

Cicindela highlandensis

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Cicindela highlandensis occurs only in Highlands and Polk counties, south central Florida. Its habitat is white, bleached sand. Many localities for this species have been destroyed by development, and some populations have been decimated by over-collecting. The Nature Conservancy has purchased habitat containing this species in Florida.

Cicindela hirtilabris

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Cicindela hirtilabris occurs during the summer months in sand scrub habitat throughout peninsular Florida. In northern Florida and the panhandle this species is replaced by C. gratiosa. Other species that occur with C. hirtilabris are C. abdominalis and C. scabrosa.

Cicindela nigrior

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Cicindela nigrior is known only from scrub habitats in Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. This species has thus far only been found in the fall at this location. Other populations of this species are known from northeast Georgia in the vicinity of Kite.

Cicindela repanda

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Cicindela repanda occurs on sand bars on the larger rivers of north central and western Florida.

Cicindela scabrosa

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Cicindela scabrosa is restricted to peninsular Florida. Its habitat is also scrub, but scrub which does not have turkey oak (Quercus laevis). Its habitat is indicated by white, bleached sand and small oaks. These habitats are small, often separated by many miles, and are frequently adjacent to pine flatwoods and wet lowlands.

Cicindela scutellaris unicolor

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Cicindela scutellaris unicolor occurs in sand ridges throughout the state of Florida. Adults are present in spring and fall. This species occurs in the same habitat with C. abdominalis, C. hirtilabris, C. gratiosa, and C. scabrosa.

Cicindela splendida

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Cicindela splendida occurs on clay banks, powerline rights-of-way, dirt roads, and mountain paths in the north Georgia mountains. This species occurs in early spring (March) and late fall, (September–October). The area around Clayton, Georgia is a good locality to find this species.

Description

Adults of Florida Megacephala are nocturnal. During daylight hours they may be found hiding under surface objects, dried algal mats on mud flats, boards, rocks, even in cracks in the ground. Adults are extremely rapid runners. Collection of these species is most easily done with headlamp and hand collecting, or with pitfall traps in suitable habitat.

Florida Cicindela are more diverse in behavior and habitat selection. One species (C. punctulata) occurs statewide in disturbed areas, along sidewalks, in open pastures, and on drier soils. This species has the unique characteristic of giving off an odor quite similar to Juicy Fruit Gum. If you don't believe this, collect an individual and sniff for yourself!

Other Cicindela species occur in Florida on river sandbars, sand scrub dunes, coastal beaches, salt marsh mudflats, coral outcroppings in the outer Florida Keys, lakeshores, wooded paths and on clay banks.

Tiger beetles are predators, feeding on insects they are able to capture with their mandibles. It is common to collect adult beetles with ant heads still attached to a variety of appendages! Rather than specializing on certain species for prey, adults are opportunistic feeders.

Active larvae sit at the top of their burrows waiting for prey to venture close enough to be grasped. Any insect not larger than the larva is potential prey, but ants seem to make up the majority of prey items for larvae of most species that have been studied.

Life Cycle

Eggs

Eggs are deposited singly in shallow depressions. Upon eclosion the 1st instar larva digs a vertical burrow in which it will remain until pupation and adult emergence. Before each molt the larva plugs its burrow.

Larvae

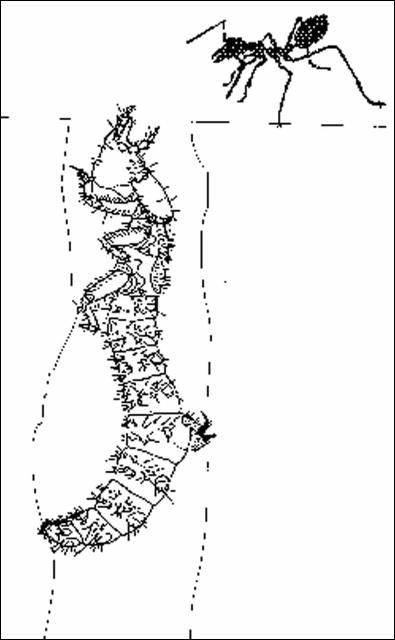

Larvae are S-shaped, with dorsal abdominal hooks (on segment 5) which are used to hold position in their vertical burrows. Some species have adapted to surviving long periods of flooding (river species). Burrows range in depth from 8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm) (Megacephala) to several feet (100 cm) (Cicindela spp.), the extreme example being that of C. lepida whose larvae have been found to burrow six feet (180 cm) deep. Larvae of Florida species (C. abdominalis, C. scutellaris, and C. hirtilabris) burrow to 30 inches. Species that occupy salt flats have larvae whose burrow depths are probably limited by the water table. The few species examined by me have been found to burrow less than one foot. Location of larval burrows has led to the demise of many populations of Cicindela dorsalis. Larval burrows have been marked in a photograph (Figure 2) taken at Anastasia State Park, Florida. Flags mark the location of C. dorsalis media larvae. Unfortunately, the usual site of burrows is also the preferred path for pedestrian and vehicular traffic on beaches in Florida. This conflict has resulted in the complete extinction of populations of this species along many beach areas on both coasts of Florida and is a topic of concern for remnant populations of other coastal tiger beetles. Among Florida species the only two whose larval habitats remain unknown are C. striga and C. olivacea.

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Credit: Paul M. Choate, UF/IFAS

Adults

Adults of most species occur only during the summer months at Florida localities (Megacephala spp., C. abdominalis, C. scabrosa, C. highlandensis, C. hirtilabris, C. gratiosa and others), while at least two species occur only during the cooler months in Florida (C. scutellarisunicolor and C. nigrior). Larvae occur during late summer and overwinter as last instars. Pupation probably occurs in springtime for summer species. Larvae occur in the same habitat as adults for many species or are found in close proximity to adult habitats for those species that occur in wet areas.

Parasites and Predators

Tiger beetles are parasitized as larvae by the Diptera family Bombyliidae and the Hymenoptera family Tiphiidae, genus Methoca and genus Pterombrus. They also are regularly preyed upon by robber flies of the Diptera family Asilidae.

Collecting Tips

Adults are active both during daylight hours and at night. During daytime hours adults are found on sandier portions of alkali flats. Nighttime activity includes mating. Individuals are readily attracted to lights, including automobile headlights, "blacklights", and mercury vapor lights. Large numbers may be collected using these attractants.

Selected References

Choate PM. 1975. "Notes on Cicindelidae in South Carolina." Cicindela 7: 71–76.

Choate PM. 1984. "A new species of Cicindela Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) from Florida, and elevation of C. abdominalis scabrosa Schaupp to species." Entomological News 95: 73–82.

Choate PM. 2003. A Field Guide and Identification Manual for Florida and Eastern U.S. Tiger Beetles. University of Florida Press. 224 pp.

Choate PM. 2003. Illustrated key to Florida species of tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Entomology and Nematology, University of Florida. http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/choate/tigerbeetle_key.pdf (3 May 2010).

Choate PM. 2008. Tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Collyrinae and Cicindelinae). In Encyclopdia of Entomology. 2nd Edition. pp 3804–3818. J.L. Capinera, ed. Springer. 4346 pp.

Graves RC, Pearson DL. 1973. "The tiger beetles of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae)." Transactions of the American Entomological Society 99: 157–203.

Hamilton CC. 1925. Studies on the morphology, taxonomy and ecology of the larvae of Holarctic tiger beetles (family Cicindelidae). Proceedings of the United States National Museum 65, Article 17: 1–87.

Roman SJ. 1988. "Collecting Cicindela scabrosa Schaupp, with notes on its habitat." Cicindela 20: 31–34.

Vick KW, Roman SJ. 1985. "Elevation of Cicindela nigrior to species rank." Insecta Mundi 1: 27–8.