The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Only two of the 18 Nearctic species of Vespula are known from Florida (Miller 1961). These are the two yellowjackets: eastern yellowjacket, Vespula maculifrons (Buysson) and the southern yellowjacket, Vespula squamosa (Drury). One species of Dolichovespula is also present: the baldfaced hornet, Dolichovespula maculata (Linnaeus). The baldfaced hornet is actually a yellowjacket. It receives its common name of baldfaced from its largely black color but mostly white face, and that of hornet because of its large size and aerial nest. In general, the term "hornet" is used for species which nest above ground and the term "yellowjacket" for those which make subterranean nests. All species are social, living in colonies of hundreds to thousands of individuals.

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Distribution

Vespula maculifrons is found in eastern North America, while Vespula squamosa is found in the eastern United States and parts of Mexico and Central America. The baldfaced hornet, Dolichovespula maculata, is found throughout most of the Nearctic region.

Identification

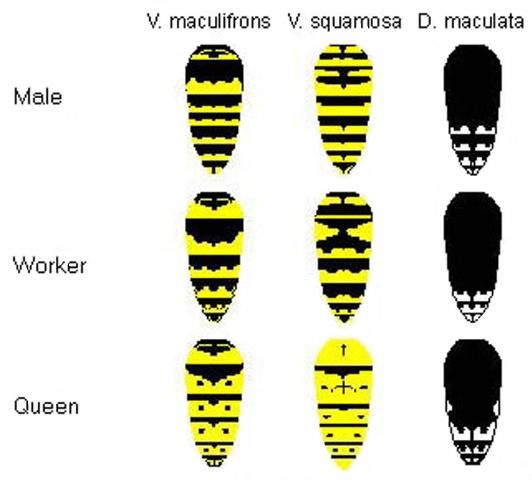

The three species of Florida yellowjackets are readily separated by differences in body color and pattern. Identification is possible without a hand lens or microscope, and, for this reason, a simple pictorial key is all that is necessary. Color patterns are relatively stable, and their use is further strengthened by morphological characters (Miller 1961). Queens and workers may be separated by abdominal patterns; males have seven abdominal segments while females have only six.

Biology

Colonies are founded in the spring by a single queen that mated the previous fall and overwintered as an adult, usually under the bark of a log. Nests may be aerial or terrestrial, depending in part upon the species of the wasp. Some species may construct both types of nests. Regardless of location, each nest is a series of horizontal combs completely surrounded by a paper envelope. Initially, the solitary queen must not only construct the paper brood cells, but also forage for food, lay eggs, feed her progeny, and defend the nest from intruders. When the first offspring emerge as adults, they assume all tasks except egg laying. The queen devotes the remainder of her life to this task and does not leave the nest again. For most of the season the colony consists of sterile worker females, which are noticeably smaller than the queen. Each worker tends to persist at a given task, such as nest building or feeding larvae, for a given day, but may change tasks if the need arises. Working habits apparently are not associated with age as they are in the honeybee. Workers progressively feed larvae a diet of masticated flesh of adult and immature insects, other arthropods, and fresh carrion. Caterpillars appear to be a favorite food. In autumn, larger cells are constructed for the crop of new queens. Larvae in these cells receive more food than do those in normal cells. At the same time, the queen begins to lay unfertilized or male eggs in either large or small cells. After emergence, the new queens mate and seek shelter for the winter. These will be the founders of next spring's colonies. The old founder queen dies, and the workers begin to behave erratically until social order breaks down. With winter's arrival, the remaining colony dies.

Baldfaced Hornet, Dolichovespula maculata (Linnaeus)

The baldfaced hornet constructs aerial nests often a foot or more in diameter. The wasp is easily recognized by its overall black and white color, and by at least half of the anterior segments of the abdomen (terga I-III) being black. Relatively little is known about this species despite its abundance and wide distribution.

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Credit: Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University; https://www.insectimages.org/

Credit: Jerry A. Payne, USDA-ARS; https://www.insectimages.org/

Eastern Yellowjacket, Vespula maculifrons (Buysson)

Most reports of the eastern yellowjacket indicate subterranean nests, but aerial nests do occur. Haviland described 10 nests, each of which had a nearly spherical ground opening about 1.5 cm (~1/2 in) in diameter. The nest looks much like that of Dolichovespula maculata except the outside envelope has the consistency of charred paper. As the nest becomes larger, workers remove soil from the burrow. The soil is always deposited about 1 cm (3/8 in) distance from the nest. According to Haviland, nests ranged from 9.5 to 30 cm (3 ¾ in–1 ft) in diameter. The largest nest contained eight levels of comb with over 2800 wasps present. Green et al. (1970) reviewed some unusual above-ground nest locations of Vespula maculifrons including decayed stumps, tree cavities, and between sidings of a home. They also found an exposed nest on the side of a building. Vespula maculifrons is most readily separated from Vespula squamosa by the color patterns.

Credit: Bruce Marlin

Credit: Georgia Forestry Commission; https://www.insectimages.org/

Southern Yellowjacket, Vespula squamosa (Drury)

As with Vespula maculifrons, both terrestrial and aerial nests are known for the southern yellowjacket. Gaul (1947) described one ground nest which was 20 cm (7 7/8 in) wide by 20 cm (7 7/8 in) deep. The nest was 22.5 cm (8 7/8 in) below the soil surface. Tissot and Robinson (1954) described five aerial nests for Vespula squamosa. Two nests were constructed in material associated with palm and another in a rolled rug in a garage. A huge nest, about 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in height, was constructed around the end of a tree stump. A total of 74 layers of comb were found. Evidence suggested that this nest might have been a coalition of two or three independently founded colonies of Vespula squamosa on the same tree.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Gerald J. Lenhard; https://www.insectimages.org/

Economic Importance and Management

These wasps perform a valuable service in destroying many insects that attack cultivated and ornamental plants. However, nests near homes may prove a source of irritation. If the nests are large or difficult to approach, for example within the walls of a house, the safest procedure would be to hire a pest control operator to eliminate the colony. Any attempt to remove or destroy nests by the layman should be done at night when nest activity is at a minimum. It is important to note that even though nests are relatively inactive at night, any disturbance will result in instant activity by the colony. It is necessary to work cautiously but quickly. Protective clothing is advisable. These wasps are adept at stinging and are especially aroused if danger threatens the nest. Unlike the honeybee, which dies upon inflicting a single sting, vespid wasps may sting as often as they find a target. In fact, when a yellowjacket or hornet is injured, it often releases an "alarm pheromone" which quickly results in an aggressive, defensive behavior from other members of the colony.

Yellowjackets and hornets are also attracted to sugar sources, such as berries and flower nectars. However, this becomes a problem when the sugar source is a food or drink being consumed by a human. Sweet items like soft drinks, ripened fruits and watermelons attract bees and wasps. Keep these items covered outdoors. Pick fruit as it ripens and dispose of rotten fruits (Koehler and Oi 2003). In school yards, parks, and other community areas ensure that lids on trash containers are either secure or able to prevent access by wasps as this potential food source (discarded drink containers, fruit remains, etc.) can attract wasps on a continual basis, leading to stinging incidents.

Credit: Jerry A. Payne, USDA-ARS; https://www.insectimages.org/

Credit: Terry Price, Georgia Forestry Commission; https://www.insectimages.org/

Selected References

Evans HE. 1963. Wasp farm. The Natural History Press, Garden City, NY. 178 pp.

Evans HE, Eberhard MJW. 1970. The wasps. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 265 pp.

Gaul AT. 1947. Additions to vespine biology III: Notes on the habits of Vespula squamosa Drury (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society 43: 87–96.

Green SG, Heckman RH, Benton AW, Coon BF. 1970. An unusual nest location for Vespula maculifrons (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 64: 1197–1198.

Haviland EE. 1962. Observations on the structure and contents of yellowjackets' nests (Hymenoptera). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 64: 181–183.

Koehler PG, Oi FM. (2003). Stinging or Venomous Insects and Related Pests. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. (no longer available online)

Landolt PJ, Reed HC, Heath RR. 1999. An alarm pheromone from heads of worker Vespula squamosa (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Florida Entomologist 82: 356–369.

Miller CDF. 1961. Taxonomy and distribution of Nearctic Vespula. Canadian Entomologist Supplement 22: 1–52.

Reed HC, Landolt PJ. 2000. Application of alarm pheromone to targets by southern yellowjackets (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Florida Entomologist 83: 193-196.

Tissot AN, Robinson FA. 1954. Some unusual insect nests. Florida Entomologist 37: 73–92.

Vetter R, Visscher PK. (2004). Yellowjacket Wasps and their Control. Insect Information. (8 February 2016) https://wasps.ucr.edu/