The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The West Indian fruit fly, Anastrepha obliqua (Macquart), occurs throughout the Caribbean, south to southern Brazil. It is the most abundant species of Anastrepha in the West Indies and Panama. Anastrepha obliqua is a major pest of mangoes in most tropical countries, making the production of some varieties unprofitable. Some varieties, however, are little damaged. Like the Caribbean fruit fly, Anastrepha suspensa (Loew), it also attacks other tropical fruits of little economic importance. Anastrepha obliqua has also been called the Antillean fruit fly.

Synonyms

Anastrepha obliqua was described originally by Seín in 1933 as a variety of Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann). The type series was from Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico. It was first reported from Florida in the early 1930s as an unnamed species.

The species was widely known by its synonym, Anastrepha mombinpraeoptans Seín, or as a variety of the continental Neotropical species, Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (Berg 1979, Weems 1970), and is one of several closely related species of Anastrepha (Weems 1980).

Anastrepha fraterculus var. mombinpraeoptans Seín, 1933

Anastrepha mombinpraeoptans Seín

Anastrepha acidusa authors (not Walker)

Anastrepha trinidadensis Greene, 1934

Anastrepha ethalea Greene (not Walker)

Anastrepha fraterculus var. ligata Costa Lima 1934

Acrotoxa obliqua (Macquart)

Tephritis obliqua Macquart

Trypeta obliqua (Macquart)

Distribution

Anastrepha obliqua is found throughout the greater and lesser Antilles, Jamaica, Trinidad, Mexico to Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador, and the vicinity of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The Brazilian population may represent an introduction of the species at the port of Rio de Janeiro.

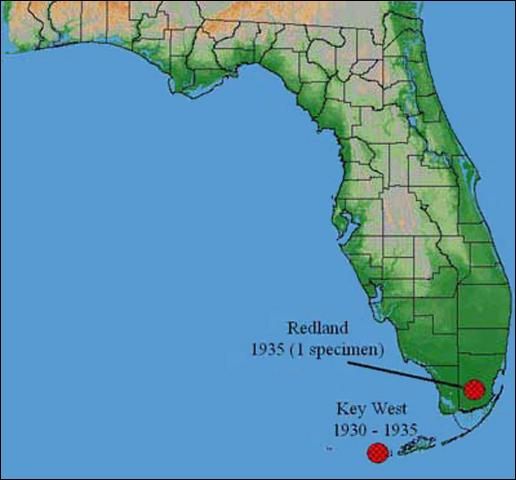

In the United States it is found in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas and was once found in Florida.

Anastrepha obliqua was first discovered in Florida in 1930. As a result of that discovery, a large fruit fly survey and eradication campaign was conducted from 1930 until 1936. Eradication actions began in 1934 and included widespread fruit removal and destruction, and biweekly insecticidal sprays. During this time, numerous Anastrepha obliqua specimens were collected, all from Key West.

Anastrepha obliqua is intercepted frequently in mangoes and several other fruits from various countries. There are Florida records for several adult females in 1957 [since disputed—specimens were probably actually collected in 1935 (Steck 2001)] from Key West and one larva in mango from Ft. Lauderdale, June 25, 1963, which was identified by Dr. R. H. Foote as "Anastrepha species, possibly mombinpraeoptans (obliqua)." In fact, this larva may have been a harbinger of the large colonization by Caribbean fruit fly, Anastrepha suspensa in south Florida, where adults were first detected in 1965 (Steck 2001).

Credit: G. J. Steck and B. D. Sutton, Division of Plant Industry

There is no confirmed evidence of the presence of Anastrepha obliqua in Florida since 1935. Apparently, the control actions of 1931–1936 indeed eradicated this pest from Florida, as no adult Anastrepha obliqua has ever again been detected in the field, despite the presence of many thousands of fruit fly detection traps that have been run throughout the Keys and peninsular Florida continuously and year-round since 1956 (Steck 2001).

Description

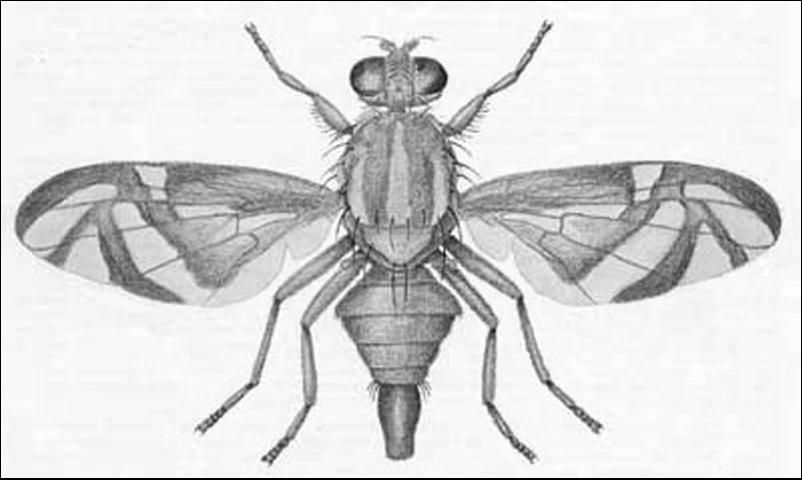

Adult

The adult is a medium-sized yellow-brown fly. The mesonotum is 2.6–3.3 mm (0.10–0.13 in) long, yellow-orange, lateral stripe from just below transverse suture to scutellum, and scutellum pale-yellow; pleura yellow-brown, a stripe below notopleuron to wing base and metapleuron paler; metanotum orange-yellow. The sides usually somewhat darkened. Macrochaetae dark brown; pile predominantly dark brownish except for a pale-yellow pile of median thoracic stripe. The wing is 5.85–7.5 mm (0.23–0.30 in) long, the bands yellow-brown, costal and S bands touching on vein R4+5; V band completely joined to S band, often broadly so.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

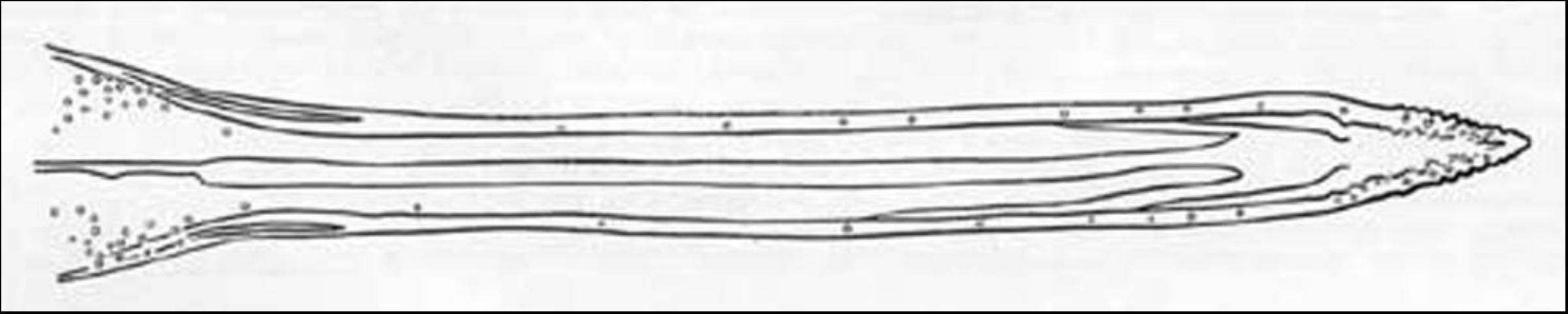

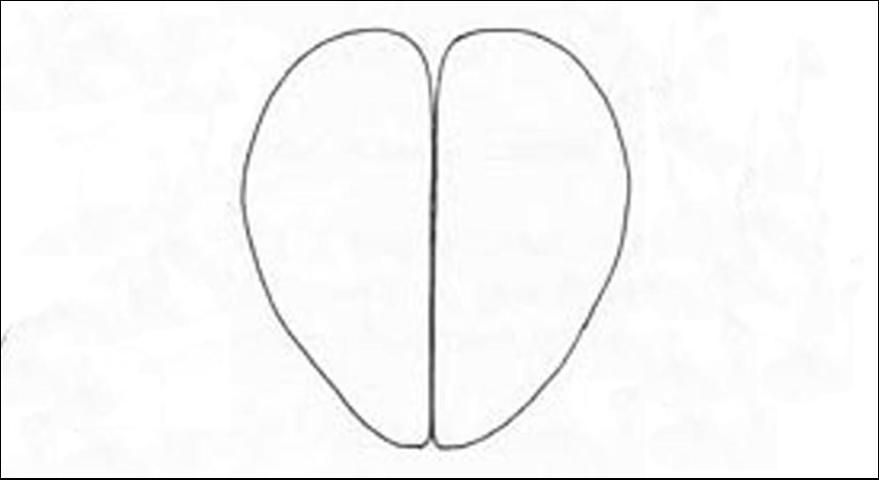

Ovipositor sheath of female 1.6–1.9 mm (0.063–0.075 in); ovipositor 1.3–1.6 mm (0.051–0.063 in) long, moderately stout, the base distinctly widened, the tip rather short, tapering, with rather acute serrations on the apical two-thirds or more. Anastrepha obliqua bears a close resemblance to Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann), but it may be distinguished by the differences in the ovipositor of the female and a combination of several characters.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

The pile of the mesoscutum is sublaterally dark brownish black, of the median stripe yellowish white, the contrast very pronounced in Anastrepha obliqua, whereas in Anastrepha fraterculus the mesoscutellar pile is rather uniformly yellow-brown, that of the sublateral stripes scarcely darker than the ground color. The black area on the side of the metanotum of Anastrepha obliqua usually reduced and the inner margin of the black area are not sharply defined, the postscutellum not darkened laterally, the wing bands usually all connected, whereas in Anastrepha fraterculus the black on the metanotum is usually extensive, and the inner margin sharply defined, the postscutellum darkened laterally, and the wing bands often disconnected.

Anastrepha suspensa (Loew) also resembles Anastrepha obliqua but differs from it in the same way as does Anastrepha fraterculus. Furthermore, Anastrepha obliqua lacks the pronounced median scutoscutellar black spot typically found in Anastrepha suspensa.

Larva

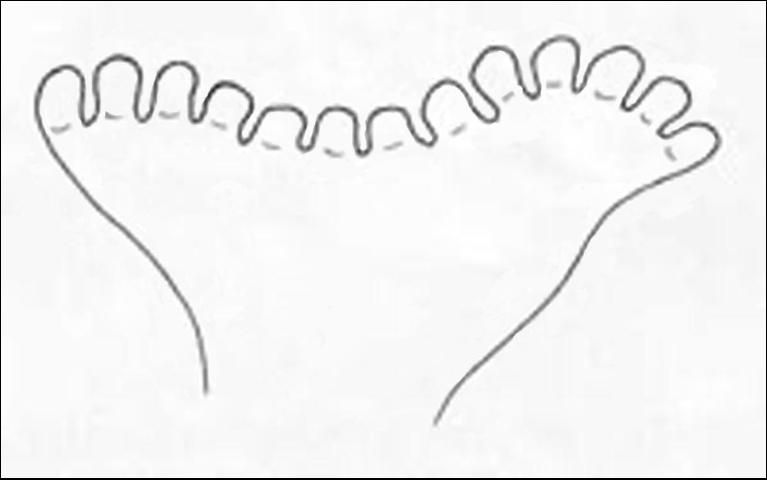

Larva white; typical fruit fly shape (cylindrical-maggot shape, elongate, anterior end narrowed and somewhat curved ventrally, with anterior mouth hooks, ventral fusiform areas, and flattened caudal end); last instar larvae range in length from 8 to 10 mm (0.31 to 0.39 in); venter with fusiform areas on segments 2 through 10; anterior buccal carinae usually 9 to 10 in number; anterior spiracles asymmetrical in lateral view with center depressed, and with tubules averaging 12 to 14 in number.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

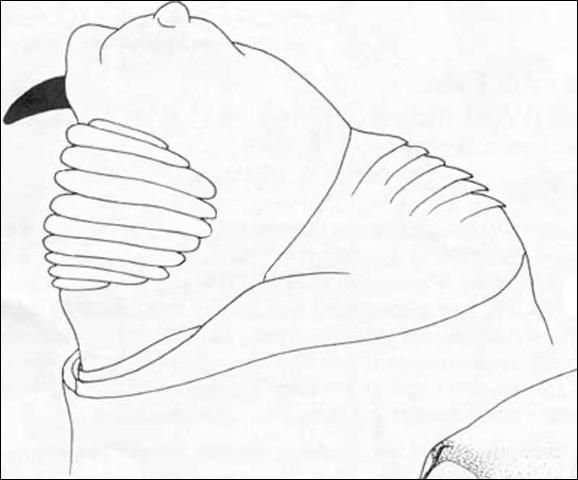

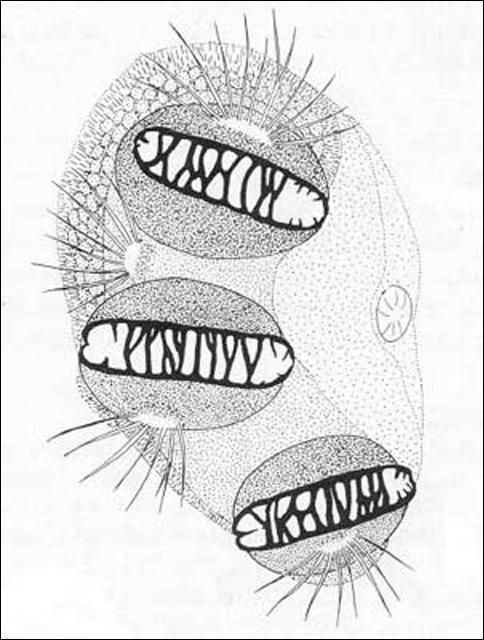

Cephalo-pharyngeal skeleton with large pointed convex mouth hook each side, with rounded dorsal lobe, and each hook about 2.5X hypostome length; hypostomium with thin subhypostomium; post-hypostomial plates curved to dorsal bridge fused with prominent sclerotized rays of central dorsal wing plate; parastomium broadly elongate; dorsal wing plate with several prominent rays and strong sclerotization on ventral border; dorsal bridge relatively evenly sclerotized, merging to a strongly sclerotized dorsal edge of pharyngeal plate; a prominent hood on pharyngeal plate.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

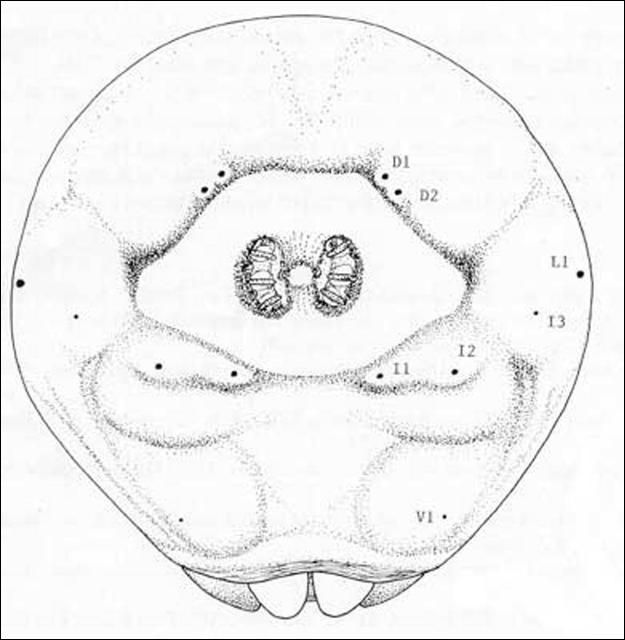

Caudal end with paired dorsal papillules (D1 and D2) close together and angled about 45 degrees from each spiracular plate; intermediate papillules 3 in number, with I1-2 in a nearly horizontal line on a slight elevation; I3 faint and distant dorso-laterally and nearer to L1 which is on dorso-lateral edge of caudal end; V1 faint and about twice as distant from I1-2 as from anal lobes; posterior spiracles as 3 elongated peritremes (length = 5X width) on each spiracular-plate, with ventral 2 peritremes angled to center from ventral direction and remaining peritreme angled from dorso-lateral angle; interspiracular processes (hairs) well developed, at 4 sites on each plate, and tips sometimes bifurcate; anal lobes entire.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Anastrepha larvae in this species complex are all relatively similar but careful observations of the buccal carinae, anterior spiracles, and papillule position of the caudal end will distinguish the species (see Heppner 1984, 1990; Steck et al. 1990). Anastrepha obliqua has anterior spiracles like Anastrepha ludens (Loew) but with fewer tubules and Anastrepha ludens usually has the anal lobes bifid. Anastrepha suspensa (Loew) is more similar but has the anterior spiracles more symmetrical than Anastrepha obliqua. On the caudal end Anastrepha ludens and Anastrepha suspensa have I1-2 angled and not horizontal like Anastrepha obliqua, while in Anastrepha interrupta Stone there also is a faint I4 present. D1-2 are closer together in Anastrepha obliqua than in the other related species. Anastrepha fraterculus has the anterior spiracles with a higher tubule number (15 through 17) than Anastrepha obliqua.

Life History

The preoviposition period in Puerto Rico varies from about a week in summer up to two to three weeks in winter. Eggs are laid singly, generally in mature green fruits except for some varieties of mangoes that may be attacked when they are very small. The larval stage lasts 10 to 13 days in summer, slightly longer in winter, and the pupal stage occupies about the same length of time. Possibly six or seven generations develop annually.

Hosts

Many host plants have been noted for the West Indian fruit fly, but due to confusion between Anastrepha obliqua and Anastrepha fraterculus, and others in this species complex, it is unclear what the true host range is for each species. Weems (1980) noted numerous tropical fruit hosts for the "fraterculus complex." A long list of recorded hosts for the West Indian fruit fly was also noted by Noorbom and Kim (1988), with mango (Mangifera indica L.), guava (Psidium guajava L.), and hog plums (Spondias sp.) being most often mentioned. Citrus is sometimes attacked in Dominica, but never in Cuba, Guyana, or Trinidad or Tobago.

Anastrepha obliqua has been recorded from many hosts belonging to the families Anacardianceae, Annonaceae, Bignoniaceae, Fabaceae, Myrtaceae, and Rosaceae. The favored food plants are the mombins, jobos, or hog plums of the genus Spondias, followed by mango, rose-apple, and guava.

- Anacardium occidentale, cashew

- Annona hayesii, pawpaw

- Averrrhoa carambola, carambola

- Citrus aurantium, sour orange; C. grandis, pumelo; C. paradisi, grapefruit

- Coffea arabica, arabica coffee

- Diospyros digyna, black sapote

- Dovyalis hebecarpa, kitambilla or Ceylon gooseberry

- Eriobotrya japonica, loquat

- Eugenia jambos, jambos, rose-apple or pomarosa; E. malaccensis, Malay-apple or pomerack; E. nesiotica

- Mangifera indica, mango

- Pouteria mammosa, sapote

- Prunus amygdalus, bitter almond; P. dulcis, almond

- Psidium guajava, guava

- Spondias dulcis, vi-apple or Otaheite-apple; S. mombin, yellow mombin; S. nigrescens; S. purpurea, purple or red mombin

The species also has been reared experimentally from:

- Annona glabra, pond-apple

- Chrysobalanus icaco, coco-plum

- Manilkara zapota, sapodilla

- Passiflora quadrangularis, a passion-flower, the giant granadilla

- Prunus persica var. nectarina, nectarine

- Vitis vinifera, California grape

Selected References

Berg GH. 1979. Pictorial key to fruit fly larvae of the family Tephritidae. San Salvador: Organ. Internac. Reg. Sanidad. Agropec. 36 pp.

Heppner JB. 1984. Larvae of fruit flies I. Anastrepha ludens (Mexican fruit fly) and Anastrepha suspensa (Caribbean fruit fly) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Entomology Circular 260: 1-4.

Heppner JB. 1990. Larvae of fruit flies 6. Anastrepha interrupta (Schoepfia fruit fly) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Entomology Circular 327: 1-2.

Norrbom AL, Kim KC. 1988. A list of the reported host plants of the species of Anastrepha (Diptera: Tephritidae). U.S. Department of Agriculture, APHIS (PPQ) 81-52: 1-114.

Pruitt JH. 1953. Identification of Fruit Fly Larvae Frequently Intercepted at Ports of Entry of the United States. University of Florida (Gainesville). MS thesis. 69 pp.

Seín F Jr. 1933. Anastrepha fruit flies in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico Department of Agriculture Journal 17: 183-196.

State Plant Board of Florida Eleventh Biennial Report for the period July 1, 1934-June 30, 1936. Jan. 1937. pp. 15-21. Anastrepha acidusa.

Steck, GJ. 2001. Concerning the occurrence of Anastrepha obliqua (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Florida. Florida Entomologist 84: 320-321.

Steck GJ, Carroll LE, Celedonio-Hurtado H, Guillen-Aguilar J. 1990. Methods for identification of Anastrepha larvae (Diptera: Tephritidae), and key to 13 species. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 92: 333-346.

Stone A. 1942. The Fruit Flies of the Genus Anastrepha. U.S. Department of Agriculture Miscellaneous Publication No. 439, Washington, DC. 112 pp.

Weems HV Jr. 1980. Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Entomology Circular 217: 1-4.

White IM, Elson-Harris MM. 1994. Fruit Flies of Economic Significance: Their Identification and Bionomics. CAB International. Oxon, UK. 601 pp.