Introduction

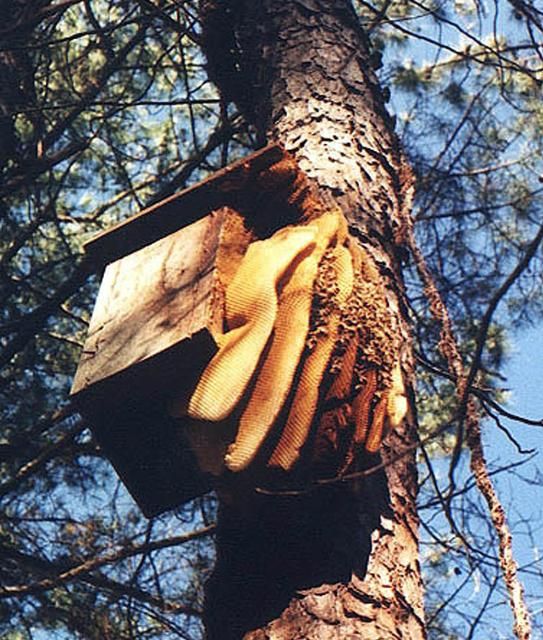

In 2005, Africanized honey bee (AHB) hybrids became established in Florida. Africanized honey bees are the same species as European honey bees (EHB) and therefore are impossible to identify by simple appearance. There are behavioral differences that make Africanized honey bees more of a problem for cavity-nesting wildlife than European honey bees. European honey bees look for cavities of about 10 gallons in volume that are clean and dry, so they will occasionally use large nest boxes as hives. Africanized honey bees will inhabit these as well as smaller nest boxes (Table 1). Wood duck, screech owl, barred owl, and barn owl nest boxes have a large enough cavity to entice European honey bees for harborage (Table 1). Africanized honey bee colonies produce 4 to 8 swarms per year compared to the 1 or occasionally 2 produced by European colonies. European honey bees have been selected to avoid swarming. Africanized honey bees will swarm as soon as they fill the space they occupy. This means that there will be many more swarms to begin feral bee colonies in areas where AHBs are established. Africanized honey bee swarms are generally smaller than European swarms because they are dividing from smaller colonies and will select any protected cavity, even burrows, irrigation valve boxes, and water meter boxes in the ground. The swarming season for African honey bees in South Florida is year-round, with a majority of swarms occurring between March and October. The other hazard associated with AHBs is that they are much more defensive of their colonies than the gentler domestic European honey bee are of theirs. AHB's nesting in residential areas or parks pose a potential risk of stings and defensive attack to people, pets, and wildlife.

The AHB has a habit of establishing colonies in unusual locations compared to European honey bees. AHBs have been found under decks, inside sheds, inside covered boats, within crawl spaces, in storm drains, in rock piles, inside soffits, in discarded tires and appliances, in woodpecker holes, and in the burrows of animals like gopher tortoises and armadillos. By using smaller and lower locations these bees may displace wildlife that uses these locations as dens in urban, agricultural, and natural environments.

Recommendations

Although these recommendations target AHB, the benefits extend to other pests as well. Put up bird and mammal nest boxes just prior to that particular animal's nesting or birthing season (Table 2). This will reduce the likelihood that honey bees and paper wasps will find and occupy it during the "off season". Take down houses or close off entrances during non-nesting seasons to discourage starlings, house sparrows, bees, and wasps.

Thoroughly treat the inside of the box and any nesting litter with the repellent pyrethroid insecticide permethrin. Only use a product that is registered for use on poultry or caged birds. If using a spray, let the material completely dry before putting up the box or allowing animals access. Research conducted 2012-2014 indicate that permethrin dust is less effective than emulsified concentrates (persistent for less than 30 days), or microencapsulated sprays (persistent for at least 60 days). Permethrin is effective in controlling blood-feeding mites, fleas, parasitic flies (Hippoboscidae, Calliphoridae), and blood-feeding bugs (Cimicidae and Rejuviidae) in addition to discouraging Africanized honey bee scouts and paper wasps. Controlling these arthropod pests may also improve survival of nestlings in treated boxes. Studies between 2012 and 2014 significantly reduced tropical fowl mites in starling nest boxes. The results of treating starling nest boxes with microencapsulated permethrin prior to nesting season were no honey bees occupying treated boxes, a significant reduction on mite load in the nests, and a significant increase in nestling survival to fledging compared to untreated nest boxes. Permethrin has very low toxicity to birds (oral LD50 >9900 mg/kg in mallard ducks and > 13,500 mg/kg in pheasants) and low toxicity in mammals (oral LD50 in rats of 430 - 4000 mg/kg and dermal LD50 in rats > 4000 mg/kg and in rabbits >2000 mg/kg) making this insecticide a good choice. Toxicity is determined by the lethal dose to kill 50% of a defined population. The larger the number, the lower the toxicity of the substance to the test organism. As a reference, the oral LD50 for table salt (NaCl) is 3,000 mg/kg for rats and 4,000 mg/kg for mice. The half life of permethrin EC in soil is about 30 days. Permethrin tick repellents for clothing are effective for six weeks, so permethrin products may give similar duration of protection inside a nest box. The microencapsulated permethrin is protected from degradation and absorption into the wood by the polymer spheres. It should protect a nest box from blood-feeding mites and insects for about 60 days, which should be enough time for nestling to fledge.

Experiments in Florida and Brazil have shown the value of the IPM method called Push-Pull. The Push is the treatment of the nest boxes with a repellent Pyrethroid to discourage honey bee scouts. More information about swarm trapping honey bees can be found at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in778. In Brazil, we gave the captured swarms to local beekeepers. In Florida, captured swarms were moved to a research apiary to be re-queened.

If Bees have Invaded your Wildlife Nest Box

If bees invade your birdhouse, bat house, or mammal den box, contact a pest management professional with bee experience or a beekeeper to remove the colony (a list of professionals to perform this service can be found at http://entnemdept.ifas.ufl.edu/afbee/bee_removal.shtml). These social insects will defend their colonies and a bee suit is usually required to remove them safely. Do not use "wasp spray" on honey bees. It will kill those bees it contacts directly, but it also causes those bees to release their alarm / defense pheromone. This excites the rest of the colony into a defensive frenzy and you will be stung unless you are wearing a bee suit. After the box is down and the bees are dead or have been relocated, scrap out all the comb and wax. Wash the inside of the nest box thoroughly with hot water and a mild detergent. After cleaning, allow the box to air dry completely, then store indoors until next nesting season.

Credit: Credit: W. H. Kern, Jr; UF/IFAS

Credit: http://www.beesource.com/eob/feral/feralhive8.htm

Summary

AHBs became established in South Florida and the Tampa area in 2005. They have spread over the peninsula of Florida and have the possibility to occupy all of Florida and the coastal plain of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. AHBs are more likely to invade bird boxes, bat houses, and den boxes than European honey bees. The use of appropriate insecticides (especially microencapsulated permethrin) may discourage AHBs, paper wasps, and parasites that feed on the blood of baby birds and mammals from moving into these valuable wildlife structures.

Other Sources of Information

Brown, L. N. 1997. Mammals of Florida. Windward Publishing, Miami, FL. 224 pp.

Maehr, D.S., H. W. Kale and K. Karalus. Florida's Birds, 2nd Edition; A Field Guide and Reference. Pineapple Press, Sarasota, FL. 359 pp.

Sanford, M. T. and H. G. Hall. 2005. African Honey Bee: What You Need to Know. ENY114/MG113. Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville FL 32611. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/MG113

Schaefer, J. 1990. Helping Cavity-nesters in Florida, SS-WIS-901, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida Gainesville FL 32611-0304. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/UW058

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following colleagues for reviewing this manuscript; Tim Broschat, FLREC, Frederick M. Fishel, UF Pesticide Information Office, Jerry Hayes, FDACS, DPI, Steve Johnson, UF/IFAS, W.E.C., Philip Koehler, UF/IFAS, Entomology and Nematology, Frank Mazzotti, FLREC, W.E.C., and Van Waddill, FLREC Center Director.