The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The green stink bug, Chinavia hilaris (Say), is a commonly encountered pest of seeds, grain, nuts, and fruit in both the nymph and adult stages across North America. This species is highly polyphagous (has many host plants) which it damages through feeding. While capable of long-distance movements to find food, the bugs are most often clumped around host plants in the optimum stage of development.

Credit: Russell F. Mizell, III, UF/IFAS

Synonyms

Chinavia hilare

Nezara hilaris

Acrosternum hilaris

Pentatoma hilaris

Distribution

The green stink bug occurs in most of eastern North America, from Quebec and New England west through southern Canada and northern US to the Pacific Coast, and southwest from Florida through California. This is the most commonly encountered stink bug species in North America. However, in Florida other stink bug species often reach higher populations than C. hilaris.

Description

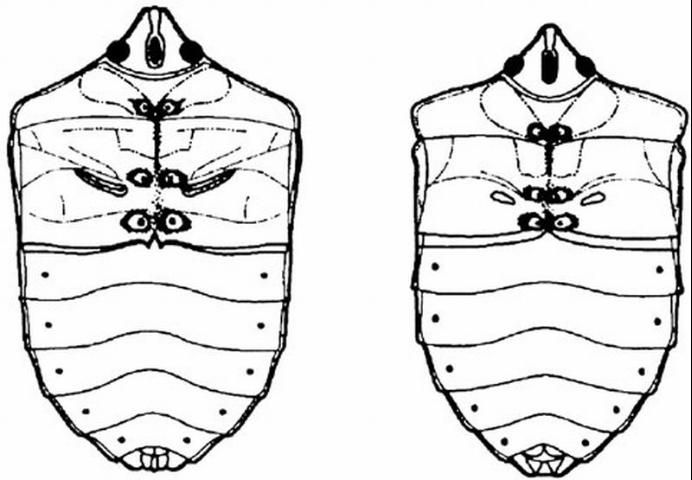

The green stink bug, C. hilaris, may be confused with the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula (Linnaeus), but can be distinguished easily by its longate ventral ostiolar canal (external outflow pathway of metathoracic scent gland), which extends well beyond the middle of its supporting plate, while that of N. viridula is shorter and does not reach the middle of its supporting plate.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Chinavia hilaris can be separated from A. pennsylvanicum by the longer head, and straight anterolateral margins in the pronotum.

Adults

Like other stink bugs, adult green stink bugs are shield-shaped with fully developed wings. They are solid light green and measure 14 to 19 mm in length. The head and pronotum frequently are bordered by a narrow, orange-yellow line. Both adults and nymphs have piercing and sucking mouthparts for removing plant fluids.

Credit: David Cappaert, Michigan State University, Bugwood.org

Credit: Susan Ellis, Bugwood.org

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

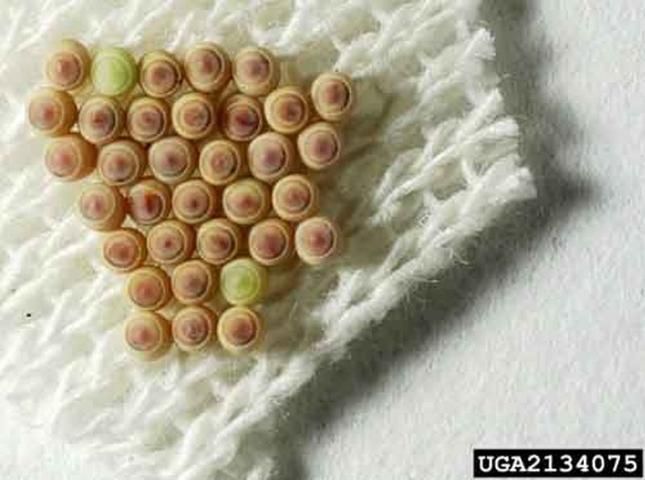

Eggs

When first laid, the eggs of the green stink bug are yellow to green, later turning pink to gray. The eggs are placed in clusters that appear as double rows of small barrels on and around suitable food and are usually attached to the underside of leaves. They measure 1.4 by 1.2 mm.

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

Nymphs

The nymphs are predominantly black when small, but as they approach adulthood, they become green, and yellow or red. However, the immature stages have a distinctive pattern of whitish spots on the abdominal segments. Their bodies are oval-shaped, and they also have short and nonfunctional wing pads which, once they reach the final instar, makes them look somewhat like adults. Several instars are often found together in high numbers because of stink bug oviposition behavior.

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

Life Cycle and Biology

Green stink bugs become active during the first warm days of spring, and this is when mating occurs. A few bugs may be present from May through June but are more common in mid to late June and taper off in fruit trees in July and August with only one generation per year. A second generation may occur in July and August.

The life cycle typically takes 30 to 45 days. The normal development from egg to adult requires about 35 days but varies with temperature. As with other Hemipterans, the green stink bug has an incomplete metamorphosis, which means that the immatures resemble the adults. Undeveloped stages go through five instars, and each time a nymph molts it looks a little more like an adult; this process takes the insect about a month.

Oviposition may occur anytime when adults are present from May through July and August. Eggs hatch in about a week. There is a significant positive relationship between female body size and fecundity. The green stink bug is univoltine (one generation a year) in northern areas and bivoltine (two generations) in its southern range reflecting its reaction to the differences in environmental conditions.

If the weather stays warm, an adult stinkbug lives about two months. During cold weather, young stink bugs will hibernate in leaf litter or under tree bark until the onset of warmer temperatures.

Laboratory experiments have demonstrated that females choose to mate with large males, while males prefer to mate with larger females. Males have direct reproductive gain by choosing larger females, but the advantages to females are not clear.

Hosts

A sequence of host plants with overlapping periods of seed and fruit production is necessary for C. hilaris to develop large populations during its annual life cycle.

Chinavia hilaris is an important pest because it has a broad range of suitable hosts. Some of its favorite hosts are black cherry and elderberry, flowering dogwood, evergreen blackberry, basswood, and pine trees. The species also attacks a large number of important economic crops, including apple, apricot, asparagus, beans, cherries, corn, cotton, eggplant, peach, pear, peas, soybean, tobacco, and tomato.

Damage

The green stink bug attacks the developing fruits of several cultivated trees, and the type of damage varies with the age of the developing fruit—the earlier feeding occurs in the development of the fruit, the more severe the damage. Injuries are usually caused by adults as the nymphs are not mobile enough to move to early-producing fruit trees like peaches or nectarines. However, in grapes, adults often lay eggs early in the season and the small nymphs will begin to suck the juices out of the maturing fruit.

While feeding, the green stink bugs inject digestive enzymes into food that liquefies the contents which they then feed upon. This action reduces the quality of the fruit or seed. The feeding wound also provides an opportunity for pathogens to gain entry.

Catfacing, which is the most severe injury to fruit such as peach, is characterized by sunken areas surrounded by distorted tissues. The surfaces are rough, corky and lack pubescence, because the tissue at the site of the feeding puncture stops growing whereas those surrounding the site do not. Another type of damage by the green stink bug is called dimpling or scarring, which is a slight depression caused by the shrinkage of the tissues injured by the feeding of the bugs. Nymphs sometimes cause considerable damage in the form of dimples. It has been shown that the most severe damage occurs in the vicinity of woodlands.

Credit: Russell F. Mizell, III, UF/IFAS

Management

Biological Control

Green stink bugs have numerous natural enemies. Birds, toads, spiders, other insect-eating animals and even other insects prey on them. The various life stages of the green stink bug may be parasitized by species of Hymenoptera and Diptera.

Credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA-ARS, Bugwood.org

Chemical Control

Insecticide application for control of stink bugs in many crops is often warranted. Consult your local UF/IFAS Extension agent for recommendations.

Selected References

McPherson JE. 1982. The Pentatomoidea (Hemiptera) of Northeastern North America with Emphasis on the Fauna of Illinois. Southern Illinois University Press. IL. pp. 86–89.

McPherson JE, McPherson RM. 2000. Stink Bugs of Economic Importance in America North of Mexico. CRC Press. Boca Raton, Florida. pp. 129–139.

Mizell RF. (2005). Stink Bugs and Leaffooted Bugs are Important Fruit, Nut, Seed and Vegetable Pests. ENY-718. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN534 (5 September 2019)

North Carolina State University Cooperative Extension. Stink Bugs. North Carolina Integrated Pest Management Information. http://ipm.ncsu.edu/AG271/soybeans/stink_bugs.html (5 September 2019)

Pickel C, Bentley WJ, Hasey JK, Day KR, Rice RE. (2006). Peach Stink Bugs. UC IPM Online. http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/r602300111.html (5 September 2019)

Schwertner CF, Grazia J. 2006. Descrição de seis espécies de Chinavia (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae, Pentatominae) da América do Sul. Iheringia (Zool.) 96: 237–248.

Schwertner CF, Grazia J. 2007. O gênero Chinavia Orian (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae, Pentatominae) no Brasil, com chave pictórica para os adultos. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 51: 416–435.

Slater JA, Baranowski RM. 1978. How to Know the True Bugs. Wm. C. Brown Company Publishers. pp 50.