Introduction

The animal production industry is one of the most hazardous industries in the United States. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported 189 fatalities and an estimated 4,670 nonfatal injuries in the animal production industry in 2019 (BLS 2021a).

The BLS investigates annual totals for injuries and fatalities but does not provide details that could be helpful to prevention efforts. Locally, nonfatal occupational injury data from the BLS are not available for Florida. Florida’s animal production industry contributes over $1.5 billion annually and involves cattle farming and ranching, as well as goat, horse, poultry, and swine farming. Additionally, the aquaculture industry brings about $100 million annually.

Occupational injuries and illnesses create a financial burden for the employees, employers, farmers, and their families. Most agricultural injuries result in hospitalization, doctor visits, and lost time at work. According to a study conducted from 2011 to 2013 by the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health (CSCASH), the average cost of serious agricultural injuries across seven states in the midwestern US was about $8,000 (Johnson et al. 2021).

The purpose of this publication is to examine nonfatal injuries and illnesses in the state of Florida’s animal production subsector. It is targeted to stakeholders, workers, and Extension educators/faculty in the industry.

Animal Production Subsector

The animal production industry is a subsector of the Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing sector (Figure 1). The animal production subsector oversees the raising or fattening of animals, aquatic plants, and ornamental fish with the intention to sell them or their byproducts (US Census 2021). The National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) reports that these products, including livestock, meat, dairy, leather, and more, constitute over 50% of agricultural goods in the US and generate billions of dollars annually (USDA NIFA 2021). The activities carried out by workers in animal production, such as the keeping, breeding, and feeding of animals, can be highly hazardous, making agriculture one of the most dangerous industries to work in.

Credit: Serap Gorucu, UF/IFAS

According to the BLS Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) conducted in 2019, the injury and illness rate per 10,000 full-time private industry workers in the US related to animal production was 211.5 (BLS 2021b). Table 1 shows a breakdown of nonfatal injury rates among the specific industry groups within this subsector for 2019.

Table 1. Nonfatal injuries among animal production workers in the US, 2019.

Gathering such data about on-the-job injuries and illnesses is important because the data can be used by farm owners, managers, and employees to identify, mitigate, or eliminate hazards (Becker and Pirozzoli 1993). This report describes the incidences of injury/illness claims for the animal production subsector in the state of Florida and takes an initial step toward preventing similar occupational injuries in the future.

Methods

The Florida Department of Financial Services’ Division of Workers’ Compensation compiled data on Workers’ Compensation from 2010 to 2019. Agricultural industries in Florida are required to have Workers' Compensation for six or more regular employees and/or 12 seasonal employees who work more than 30 days (FDFS 2022). Therefore, it is likely that the number of work-related injuries/illnesses among animal production workers is greater than the number of cases reported in this data set. Industries were classified by the 2017 North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). The NAICS code for the animal production and aquaculture subsector is 112.

Data on Workers’ Compensation include the date of each accident, if the injury resulted in death, nature of the accident, injured body part, cause of injury, city, state, county, zip code, and 4- or 6-digit NAICS codes. Over the study period, 3,947 claims were related to the animal production and aquaculture industries in Florida. Additionally, three injuries that resulted in death and 13 injury claims with locations in other states were listed, but they were excluded from the final data set. Data analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel and maps were developed using Tableau Desktop.

Results

From 2010 to 2019, 3,947 Workers’ Compensation claims were reported among workers in animal production (NAICS 112) in Florida, with approximately 394 claims filed per year (Table 2). Since 2010, there was a 26.4% decrease in the number of cases despite an increase in employment of 14.2%. Additionally, the injury claim rate decreased by almost 35%, from 889 claims to 573, per 10,000 employees. The claim rate was at its lowest point in 2016. Over the decade, there were no significant discrepancies between the numbers of injuries for each month. The number of claims per month ranged from 288 in November to 371 in March. Overall, claim rates per 100 employees were between the lowest (4.58) in 2016 and the highest (9.84) in 2012 (Table 2).

Table 2. Trends in employment and Workers’ Compensation injury claims.

Table 3 presents the injury/illness claim distributions for the animal production and aquaculture industry groups. The cattle ranching and farming industry represents the majority (82.8%) of the total injury claims in animal production.

Table 3. Injury/illness claims per industry group.

Claims by County

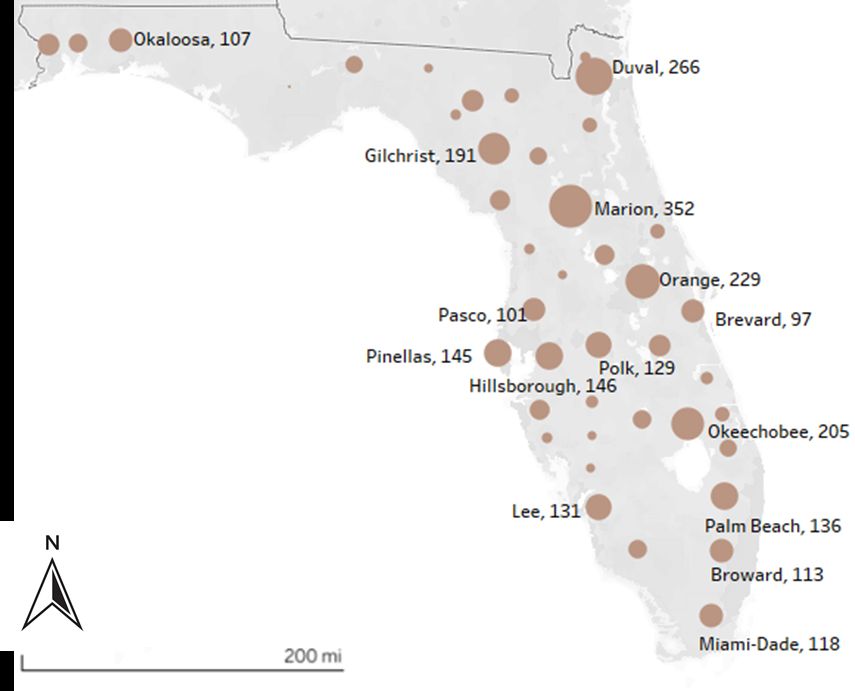

Figure 2 depicts the total number of injury claims by county from 2010 to 2019. Marion County has the highest number with 352 claims, followed by Duval County (n=266), Orange County (n=229), and Okeechobee County (n=205).

Credit: Serap Gorucu, UF/IFAS

Body Part Injured and Nature of Injury

The upper (e.g., arm, wrist; 28.4%) and lower (e.g., hip, leg; 26.6%) extremities were the most commonly injured body parts, comprising 2,170 of all injuries claimed. The trunk accounted for 1,030 (26.1%) of the injuries. The 442 claims reported involving multiple body parts and the 303 claims for the head and neck accounted for a combined 18.8% of claims. Body parts were not specified in the data set for two cases.

Regarding the nature of injuries, “strains or tears” occurred most frequently (n=1,400) (Table 4). This category made up almost three times as many claims as contusions (n=444), the second most common nature, followed by “sprain or tear” (n=423) and fractures (n=389). The remaining 40 injury types based on nature varied and comprise only one-third of the total injury claims.

Table 4. Top ten types (or natures) of injury/illness claims made in Florida, 2010–2019.

Major Cause of Injuries/Illnesses

The “strain or injury by” category makes up the majority of injury causes (39.6%). Within this category, lifting resulted in the highest number of claims (n=766). Next, the “fall, slip, or trip injury” category accounted for 774 (19.6%) of the total causes of injuries, followed closely by the “struck or injured by” (19.4%) category. Table 5 provides more information about the causes of injury/illness claims.

Table 5. Number of claims filed in Florida (2010–2019) by cause of injury.

Summary

In this study, we investigated nonfatal injury/illness claims for animal production workers in Florida from 2010 to 2019. The data provided a total of 3,947 injury/illness claims. Workers in the cattle ranching and farming industry generated the vast majority of claims (n=3,268). Over the ten-year study period, the number of injury/illness claims decreased by 26.4 percent.

Based on these findings, the body parts that are most at risk of injury are the upper (e.g., arm, wrist; 28.4%) and lower (e.g., hip, leg; 26.6%) extremities, which make up 55% of cases. Strains and sprains were the most frequently reported injury types in the animal production industry. Lifting, pushing, or pulling are routine tasks for animal production workers, and these types of tasks may cause strains or sprains (Miller and Brown-Reither 2015). Injuries occurred all year round. Injury and illness claims were not limited to a particular region in Florida, but most claims were made in Marion County.

Although Workers’ Compensation data can help us to identify specific details about injuries recorded through claims, the demographics and the narrative description of injury/illness cases were not provided in the data. This poses a challenge to building specific intervention programs. Additionally, based on Florida’s current reporting regulations, it is likely that the number of work-related health detriments that occurred exceeds the number captured by this source. Accurate and detailed surveillance to capture incidences of injuries among all animal production workers is critical for implementation of effective prevention programs.

Additional Information and Resources

OSHA, “Module 6—Hazards: Animal Handling and Farm Structures”: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/2018-12/fy11_sh-22318-11_Mod_6_AnimalsInstructorNotes.pdf

Show Me Farm Safety, “Working with Livestock”: https://farmsafety.mo.gov/livestock/

UMASH, “Farm Safety Check: Livestock Facilities & Handling Safety”: http://umash.umn.edu/farm-safety-check-livestock-facilities-handling-safety/

PennState Extension, “Animal Handling Tips”: https://extension.psu.edu/animal-handling-tips

University of Missouri Extension, “Animal Handling Safety Considerations”: https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/g1931

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Dr. Glenn Israel for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this publication along with the entire SCCAHS Evaluation Team and the UF College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Active Learning Program for their partnership and support in conducting this study.

References

Becker, W. J., and H. Pirozzoli. 1993. “Agricultural Occupational Injuries and Illnesses in Florida.” AE-240. University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved from https://nasdonline.org/

BLS. 2021a. “Industries at a Glance, Animal Production.” Accessed July 16, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag112.htm

BLS. 2021b. “Nonfatal Cases Involving Days away from Work: Selected Characteristics (2011 Forward) (Years: 2011–2019).” Washington, D.C.: Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses, U.S. Department of Labor. Accessed July 18, 2021. https://data.bls.gov/PDQWeb/cs

BLS. 2021c. “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.” U.S. Department of Labor. Accessed July 28, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/cew/data.htm

FDFS. 2022. “Florida Department of Financial Services Division of Workers’ Compensation: Coverage Requirements.” Accessed January 31, 2022. https://www.myfloridacfo.com/division/wc/employer/coverage.htm

Johnson, A., L. Baccaglini, G. R. Haynatzki, C. Achutan, D. Loomis, and R. H. Rautiainen. 2021. “Agricultural Injuries among Farmers and Ranchers in the Central United States during 2011–2015.” Journal of Agromedicine 26(1): 62–72.

Miller, R., and A. Brown-Reither. 2015. “Preventing Back Injury While Working in Agriculture.” Utah State University Extension. Accessed April 7, 2022. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curtag/1/

US Census. 2021. “North American Industry Classification System: Crop Production 2017 Definition.” Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/naics/?input=112&year=2017&details=112

USDA NIFA. 2021. “Animal Production.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.nifa.usda.gov/topics/animals