Introduction

Controlled environment agriculture (CEA), which includes hydroponics, offers year-round plant growth with less water and land use (Cabrera-Garcia et al. 2024). Hydroponics is a technique of growing plants in a nutrient-rich water solution without soil and is becoming more popular because of its reduced water use compared to traditional farming (Boylan 2020). One common method is the nutrient film technique (NFT), often used to grow leafy vegetables with short growth durations (Mullins et al. 2023). However, maintaining nutrients at the right combinations and levels is crucial to achieving good produce yield, quality, and resource use efficiency (Sanchez et al. 2023). As a result, hydroponic growers rely on simple tools like electrical conductivity (EC) sensors for nutrient management (Brechner and Both 2013), which often targets maintaining a set EC level. For example, lettuce cultivation in NFT involves maintaining EC at 1.2 dS m-1 during germination and 1.5–1.8 dS m-1 during production. Growers maintain EC at a desired level by injecting commercially available premixed fertilizers dissolved in deionized water (Brechner and Both 2013; Henry et al. 2018). A common premixed fertilizer includes Chem Gro Formula (8-15-36), along with calcium nitrate (Ca(NO3)2) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO4). While NFT is considered an efficient plant production method, there is limited information on whether EC-based nutrient dosing is suitable for increasing plant nutrient use and reducing losses. This publication aims to highlight the inefficiencies of using a single-rate, EC-based, NFT nutrient dosing practice for lettuce production throughout the growing season. The information contained in this document is relevant to a diverse audience, including students, researchers, Extension agents who have some level of understanding about controlled environment agriculture (CEA) and water and fertilizer management techniques, and hydroponic growers.

Commonly Used Nutrient Solution in Hydroponics

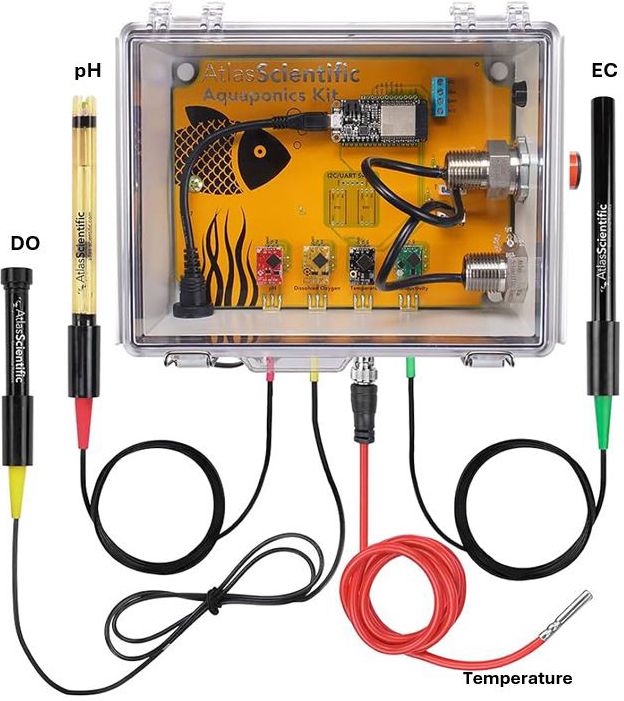

Hydroponic growers commonly utilize commercially available premixed fertilizers, such as Chem Gro Formula (8-15-36), along with calcium nitrate (Ca(NO3)2) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO4). A reservoir is regularly replenished with a nutrient solution and deionized water. Nutrient replenishment is guided by EC measurement (Figure 1).

Credit: Atlas Scientific. Used with permission.

Importance of Electrical Conductivity (EC) for Nutrient Management

Growers often rely on quick techniques like measuring electrical conductivity (EC) to monitor nutrient levels in hydroponic solutions. However, EC-based dosing can be inefficient. A high EC reflects a high nutrient concentration, while a low EC indicates the opposite. Hydroponic nutrient management typically involves maintaining a target EC to ensure the optimal nutrient balance for plant growth. Sensors continuously track EC throughout the plant's growth cycle, and when levels fall below the set point, fertilizer is added to restore the desired concentration. Although sensor-based monitoring and automated dosing enhance precision, they have limitations. The sensors used in this study required frequent calibration to address drift issues. They also needed regular cleaning because they were susceptible to biofouling. Furthermore, while the study assumed even mixing within nutrient reservoirs, uneven mixing could have caused fluctuations in sensor readings. Care was also taken to place the nutrient and acid dosing lines at an appropriate distance from the sensors, allowing sufficient time between readings for proper mixing.

Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) Study for Lettuce Production

Lettuce was grown in an indoor controlled environment growth chamber at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS), Gainesville, FL (29.6N, 82.3W), with day and night temperatures of 24oC and 19oC, respectively. The study lasted 35 days under two salinity levels, with electrical conductivity (EC) of 1.2 dS m-1 and 1.6 dS m-1, representing low and high fertilizer uses (dosing rates). The goal was to assess the effect of salinity (fertilizer dosing rate) on lettuce growth, yield, and nutrient use efficiency. Four separate nutrient film technique (NFT) systems were set up for each salinity level, each with a reservoir and 24 plants. Salinity levels were monitored using EC sensors. When the EC fell below the set points (1.2 dS m-1 or 1.6 dS m-1), a nutrient solution with fixed proportions, as detailed in Table 1, was added to restore the desired EC level.

Table 1. Composition of commercial fertilizer used in hydroponic systems. Chem Gro Formula (8-15-36) with Ca(NO3)2 and MgSO4 is regularly replenished with a nutrient solution and deionized water. Nutrient replenishment is guided by measurements such as electrical conductivity (EC).

Effect of Salinity on Nutrient Use

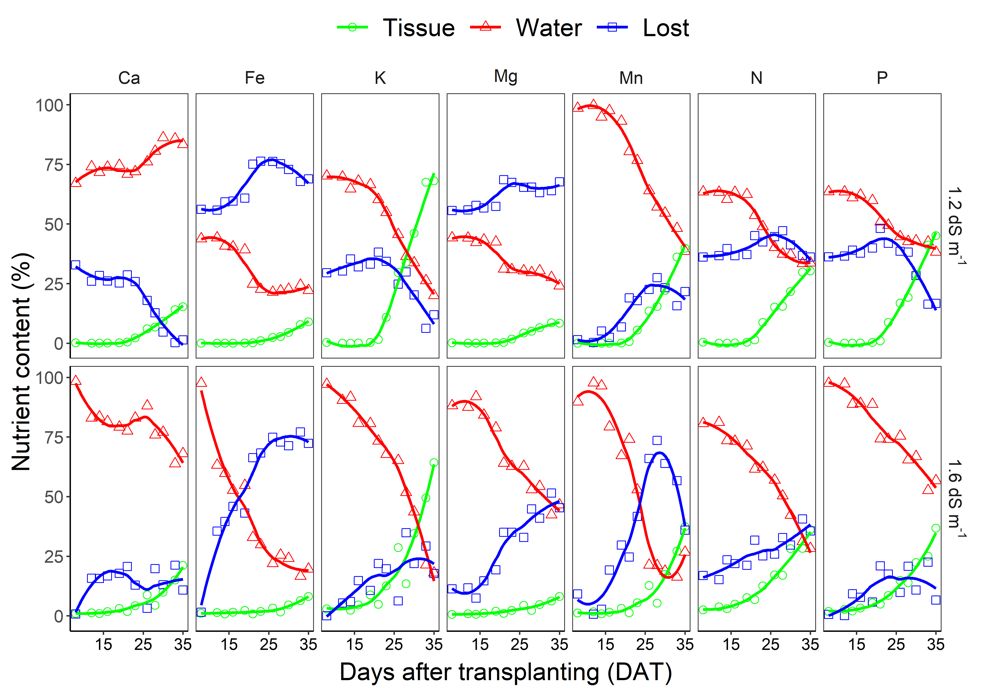

Results from the 35-day experimental period confirmed that most nutrients either remained in the water solution or were lost to the environment through various mechanisms. Only small fractions of most elements were assimilated into the lettuce biomass (Figure 2). The salinity effect was not observed on lettuce biomass and nutrient uptake. Although not conclusive, there were slight improvements in the assimilation of potassium (K), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and manganese (Mn) after day 20. Conversely, concentrations of elements in the nutrient solution declined while the percentage of nutrients lost increased for most elements as the lettuce plants matured.

Credit: Kelsey Vought and Haimanote Bayabil, UF/IFAS

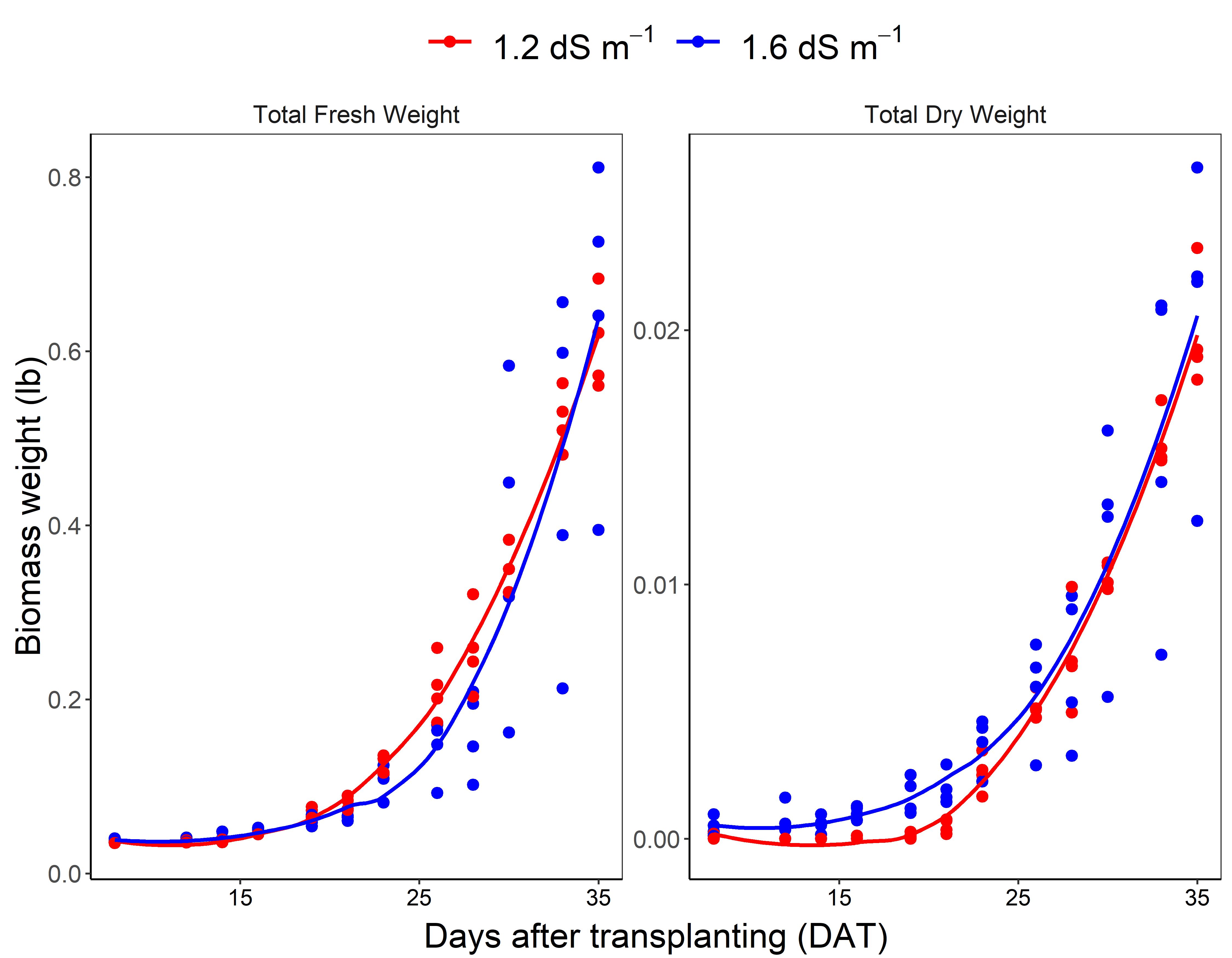

Elevated nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and calcium (Ca) concentrations in the nutrient solution of both EC levels at the end of the 35-day experiment indicate that more nutrients were added than the plants required. Cations, such as Ca, Mg, and K, when abundant in nutrient solutions, could have antagonistic effects, influencing each other’s uptake (Corrado et al. 2021). Losses of elements were calculated as the mass of element added minus the mass of element in the nutrient solution and lettuce tissue. In the 1.6 dS m-1 scenario, more elements were added than the lettuce plants could take up. This suggests hydroponic growers could reduce fertilizer solution to an EC value of 1.2 dS m-1 without affecting lettuce growth. The results of the lettuce biomass comparison are provided later in this article (Figure 3).

Credit: Kelsey Vought and Haimanote Bayabil, UF/IFAS

Table 2 summarizes the distribution of elements added to the plant tissue, nutrient solution, or loss based on average values from the two salinity levels. Potassium (K) had the highest percent assimilated in plant tissue at 20.3%, while only 2.5% of the iron (Fe) added ended up in plant tissue. In plant tissues, nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) percentages were 12.1% and 12.6%, respectively. Conversely, iron (Fe) had the highest loss percentage at 61.4%, followed by magnesium (Mg) at 45.6%. Overall, more than 50% of all elements, except iron (Fe), remained in the water solution, with calcium (Ca) having the highest percentage (78.1%). These findings underscore the inefficiency of the current hydroponic nutrient dosing system, which relies on replenishing nutrient solutions with fixed proportions based on electrical conductivity readings. Instead, the lower EC value (1.2 dS m-1) with adaptive changes of nutrient rate with plant need could be an effective technique for improved nutrient use efficiency.

Table 2. Summary of the fate of nutrients added in the NFT system growing lettuce.

Effect of Salinity on Lettuce Biomass

The effect of salinity level on the fresh and dry lettuce biomass was minimal (Figure 3). Higher amounts of fertilizer applied under the high electrical conductivity (1.6 dS m-1) did not enhance lettuce growth and biomass. This contrasts the general assumption that higher fertilizer uses lead to increased growth.

Summary and Implications of Study Findings

This Ask IFAS fact sheet provides a comprehensive dataset essential for enhanced hydroponic nutrient management. It offers ways for commercial hydroponic growers to improve nutrient use efficiency in NFT systems without compromising yield or quality. Hydroponic nutrient management strategies should prioritize providing essential nutrients to plants in the correct proportions, taking into consideration the growth stage.

Key findings and recommendations from the study include the following:

- There are critical inefficiencies in nutrient utilization in hydroponic NFT systems, with many added elements lost to the environment or remaining unused in the water. These lost nutrients can lead to environmental issues, such as water pollution.

- Continuously replenishing premixed nutrient solutions to maintain a constant EC level (1.2 dS m-1 or 1.6 dS m-1) is ineffective, resulting in significant nutrient waste and increased costs.

- Findings of this study suggest that NFT systems could be set up with an initial EC value of 1.2 dS m-1, and further in-season nutrient applications should be aligned with the growth stages of lettuce to maximize nutrient uptake efficiency.

- Using premixed commercial fertilizers with fixed nutrient proportions does not allow for targeted nutrient application based on plants' specific needs at different growth stages. Therefore, we suggest a single-element fertilizer to be purchased and mixed with a desired amount of each nutrient. Specific examples of nutrient solution formulation methods can be found in Hochmuth and Hochmuth (2021).

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture - Sustainable Agricultural Systems (NIFA-SAS) Coordinated Agricultural Project (CAP) project #2023-69012-39038, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

The authors also thank Dr. Ying Zhang for allowing the use of the NFT setup and Jean Pompeo and Daniel Crawford for their assistance in data collection.

References

Brechner, M., and A. J. Both. 2013. Hydroponic Lettuce Handbook. Cornell Controlled Environment Agriculture. https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.cornell.edu/dist/8/8824/files/2019/06/Cornell-CEA-Lettuce-Handbook-.pdf

Boylan, C. 2020. “The Future of Farming: Hydroponics.” PSCI. Princeton University. https://psci.princeton.edu/tips/2020/11/9/the-future-of-farming-hydroponics

Cabrera-Garcia, J., R. Milhollin, and M. Ernst. 2024. “Controlled Environment Agriculture: Hydroponic Farming.” University of Missouri Extension. https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/g6986

Corrado, G., V. De Micco, L. Lucini, B. Miras-Moreno, B. Senizza, G. Zengin, C. El-Nakhei, S. De Pascale, and Y. Rouphael. 2021. “Isosmotic Macrocation Variation Modulates Mineral Efficiency, Morpho-Physiological Traits, and Functional Properties in Hydroponically Grown Lettuce Varieties (Lactuca sativa L.).” Frontiers in Plant Science 12:678799. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.678799

Henry, J., C. Curry, W. G. Owen, and B. Whipker. 2018. “Nutritional Monitoring Series: Lettuce (Lactuca sativa).” e-GRO. https://hortamericas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/e-gro-Nutritional-Factsheet-Lettuce.pdf

Hochmuth, J. G., and R. C. Hochmuth. 2021. “Nutrient Solution Formulation for Hydroponic (Perlite, Rockwool, NFT) Tomatoes in Florida: HS796/CV216, rev. 9/2018.” EDIS 2018 (5). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cv216-1990

Mullins, C., A. Vallotton, J. Latimer, T. Sperry, and H. Scoggins. 2023. “Hydroponic Production of Edible Crops: Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) Systems.” VCE Publications. https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/pubs_ext_vt_edu/en/SPES/spes-463/spes-463.html

Sanchez, E., F. Di Gioia, R. Berghage, N. Flax, and T. Ford. 2023. “Hydroponics Systems and Principles of Plant Nutrition: Essential Nutrients, Function, Deficiency, and Excess.” PennState Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/hydroponics-systems-and-principles-of-plant-nutrition-essential-nutrients-function-deficiency-and-excess