Introduction

Body condition score (BCS) is a visual assessment of the fat cover (energy reserves) at key locations on a cow’s body. It is often positively correlated with reproductive success during the breeding season (Kunkle and Sand 1990). However, in some scenarios, pregnancy success was not affected by BCS at calving in Bos taurus beef females managed and selected for decades to perform in extensive rangeland conditions (Mulliniks et al. 2012) and by cow BCS change from calving until the start of the breeding season in Bos indicus beef cows grazing warm-season grasses and submitted to estrus synchronization protocols (Carvalho et al. 2022). Combined, these results indicate that the specific consequences of BCS at calving and BCS change from calving until the start of the breeding season on pregnancy success of beef cows need to be evaluated across multiple cattle breeds, particularly in scenarios of natural breeding when no exogenous hormones and estrus synchronization are implemented.

This publication was developed to help beef cattle producers understand the impacts of cow BCS before and after calving on cow and calf productive performance in Florida. For more details on how to measure BCS, see Ask IFAS publication AN347, “How to Measure Body Condition Score in Florida Beef Cattle” (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AN347). For more details on how to implement a supplementation strategy before calving to increase cow BCS, see Ask IFAS publication AN387, “Precalving Nutrition of Beef Females in Florida”(https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AN387).

The Experience at the UF/IFAS Range Cattle Research and Education Center

From 2016 to 2023, multiple studies at the UF/IFAS Range Cattle Research and Education Center (Ona, FL) gathered performance data on 1,180 fall-calving Brangus crossbred cow-calf pairs. Briefly, in August of each year (2 weeks after weaning), mature, pregnant cows were assigned to bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum) pastures (6 to 14 cows and 12 to 24 acres per pasture; 12 to 20 pastures per study) at approximately 90 days before calving. Cows were divided in two groups. One group received supplementation of protein and energy from August until calving (October/November), whereas the second group of cows did not receive supplemental feed. Starting in December and during the breeding season (January to March), all cow-calf pairs were offered stargrass (Cynodon nlemfuensis) hay and 4 lb of sugarcane molasses + urea per cow daily (20% crude protein and 75% total digestible nutrients). Calves were then weaned at 7 to 9 months of age (July of the subsequent year). For the statistical analysis, all cows were sorted into two groups: cows calving with a below-optimal BCS (BCS < 5; scale of 1 to 9), and cows calving with an optimal or above-optimal BCS (BCS ≥ 5). Then, within each group, cows were sorted into those that lost, maintained, or gained BCS from calving until the start of the breeding season (Table 1). This publication was developed using the major results of this retrospective analysis (Moriel et al. 2024).

Maternal Reproductive Success

In Florida, fall-calving beef herds are often provided an adequate quantity of mature perennial grass to graze during fall, but forage nutritive value gradually declines as the season progresses (Vendramini et al. 2023). These forage conditions explain the fact that most cows in our analysis calved with BCS ≥ 5 and lost BCS from calving until the start of the breeding season and during the breeding season (Table 1). Cows that calved with a BCS ≥ 5 also had greater BCS during the breeding season and at the time of weaning compared to cows that calved with a BCS < 5, whereas cows that gained BCS from calving until the start of the breeding season had the greatest BCS during the breeding season and at weaning, and cows that lost BCS after calving had the lowest BCS during the breeding season and at weaning (Table 1).

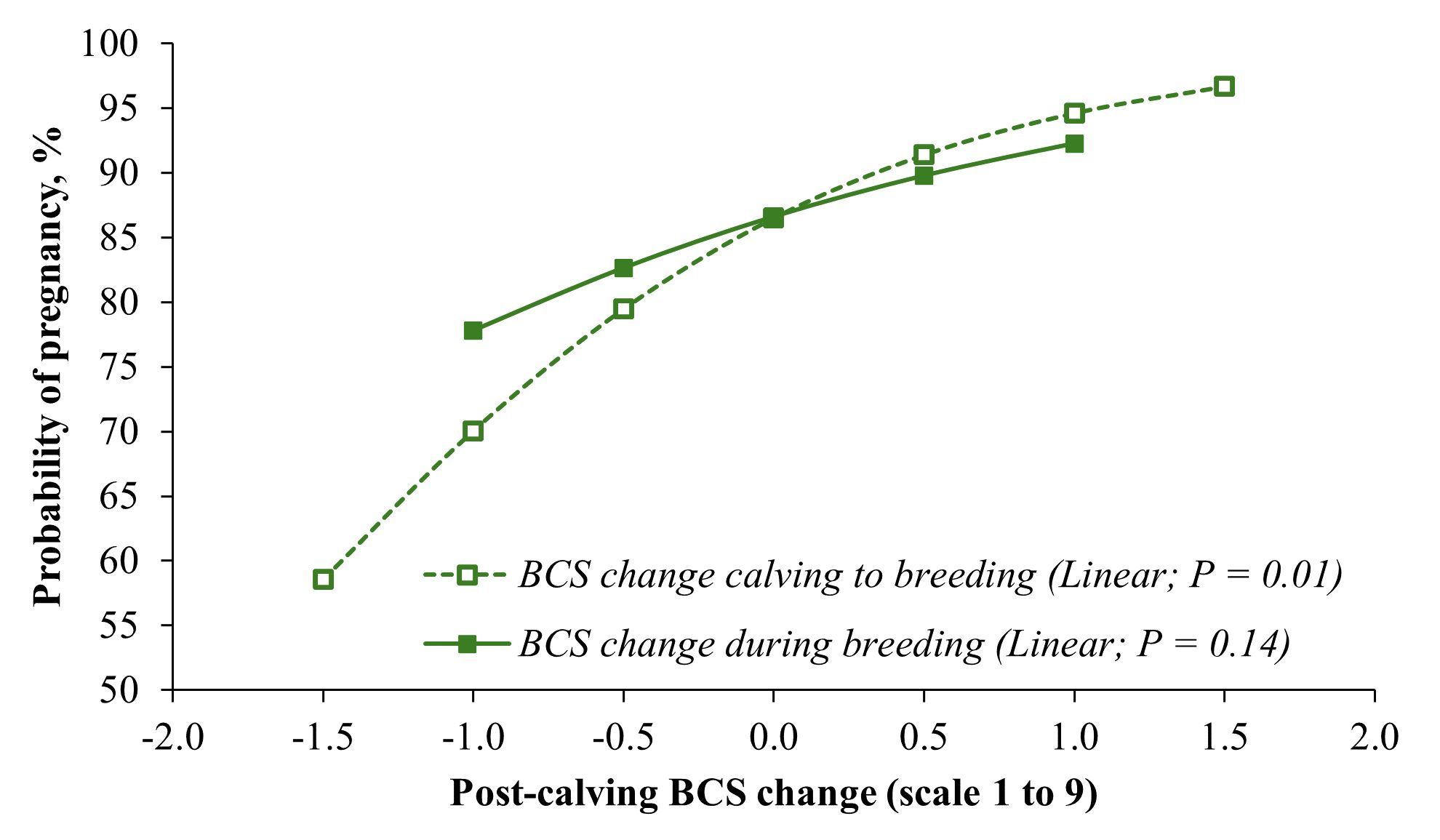

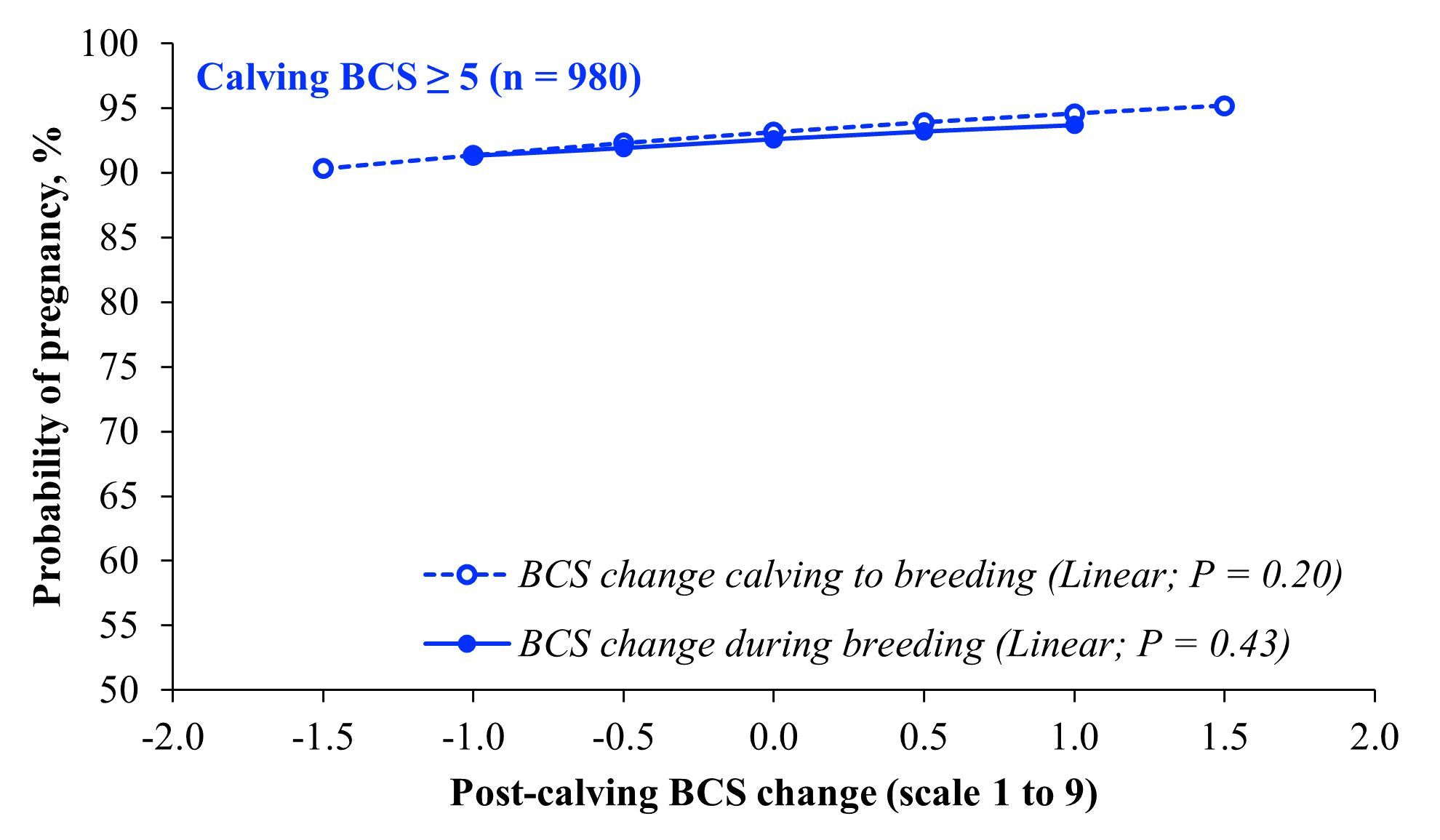

Our assessment also detected that pregnancy percentage, calving percentage, and percentage of cows calving within the first 30 days of the calving season depended on the combined effects of cow BCS at calving and a cow's subsequent BCS change from calving until the start of the breeding season (Table 2). For cows calving with a BCS < 5, pregnancy percentage, calving percentage, and calving distribution in the first 30 days of the calving season were similar between those that maintained or gained BCS from calving until the start of the breeding season; however, both groups had better pregnancy percentages compared to cows that lost BCS. Pregnancy percentage among cows calving with a BCS ≥ 5 was not impacted by their BCS change from calving until the start of the breeding season (Table 2). We detected a linear increase in probability of pregnancy as BCS change from calving until the start of the breeding season increased in cows calving with a BCS < 5 (Figure 1). In contrast, the probability of pregnancy was not impacted by cow BCS change from calving until the start of the breeding season when cows calved with a BCS ≥ 5 (Figure 2). Our results emphasized the importance of nutritional management before calving and from calving to breeding when no exogenous hormones were administered, and cows were exposed to bulls for natural breeding.

Credit: Adapted from Moriel et al. (2024)

Credit: Adapted from Moriel et al. (2024)

Calf Performance

Cow BCS change from calving to the start of the breeding season did not impact calf growth performance. However, calf body weight (BW) at birth increased by 4 lb and calf BW at weaning increased by 17 lb for calves born to cows that calved with a BCS ≥ 5 compared to BW at birth and BW at weaning for calves born to cows that calved with BCS < 5 (Table 1). Despite the heavier body weight at birth, no signs of calving difficulty were observed. Hence, the increased calf BW at birth and weaning reported herein and by others (Moriel et al. 2021) are probably the result of greater precalving BCS change of cows calving with a BCS ≥ 5 compared to cows calving with a BCS < 5, which is an indicator of improved cow nutritional status during late gestation. The inconsistent effects of maternal BCS at calving on subsequent calf weaning BW were also reported in studies that implemented or did not implement prepartum supplementation of protein and energy (Moriel et al. 2021) and may be explained by the effects of breed (Bos indicus vs. Bos taurus) (Cooke et al. 2020).

Cow BCS after Weaning vs. Cow BCS at Calving

To facilitate nutritional planning and to make sure cows are calving at an above-optimal BCS (BCS ≥ 5), producers can evaluate the BCS of cows on the day of weaning (when all cow-calf pairs are brought up to the cow pens) or at approximately two weeks after weaning. The sooner after weaning, the better; the longer you wait to evaluate the BCS of these cows, the less time you will have to act and implement a feasible supplementation strategy. Figure 3 shows the correlation between cow BCS two weeks after weaning (90 days before calving) and subsequent BCS at calving for cows that either received (SUP) or did not receive (NOSUP) precalving supplementation of protein and energy (on average, 2.5 lb per cow daily of either sugarcane molasses + urea, dried distillers grains, bakery waste, or range cubes). All cows grazed bahiagrass pastures during this period, and further details about the options of supplementation strategies were discussed in Ask IFAS publication AN387, "Precalving Nutrition of Beef Females in Florida" (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/an387). Overall, there is a strong correlation between cow BCS after weaning and subsequent BCS at calving. However, the resulting BCS at calving depended on whether cows received precalving supplementation or not. We observed that: NOSUP cows that had a BCS < 5 after weaning either gained a very small amount of BCS or maintained the same BCS, and, consequently, these cows calved at a BCS < 5; and NOSUP cows that had a BCS ≥ 5 after weaning lost BCS during the precalving period, but still managed to calve at a BCS ≥ 5. Thus, producers should expect a BCS loss from weaning until calving in most cows when no precalving supplementation is provided, which may or may not reduce subsequent reproductive success (as discussed above). In contrast, we also observed that: SUP cows that had a BCS < 5 after weaning gained nearly 1 unit in BCS during the precalving period and calved at a BCS of 5.1 to 5.3; and SUP cows that had a BCS ≥ 5 after weaning either lost a minor amount of BCS or maintained their BCS during precalving period, but all SUP cows calved at a BCS ≥ 5. As discussed in Ask IFAS publication AN387, precalving supplementation of protein and energy is a viable strategy to increase BCS or to ensure that cows calve at a BCS ≥ 5 (optimizing their reproductive success) and to simultaneously increase calf body weight at weaning by approximately 25 lb (compared to no precalving supplementation).

Credit: Adapted from Moriel et al. (2024)

Conclusion

In terms of cow reproductive performance, data presented herein reinforced that: cow BCS at calving remained a key factor driving pregnancy success in fall-calving beef cows in Florida; cow BCS loss from calving until the start of breeding season further reduced pregnancy percentage, calving percentage, and calving distribution during the first 30 days of calving in cows calving with BCS < 5; and despite the lower BCS at calving, thinner cows that maintained or gained BCS from calving until the start of the breeding season achieved similar pregnancy percentage, calving percentage, and early calving distribution compared to cohorts that calved with a BCS ≥ 5 and lost BCS after calving. In terms of calf performance, increasing cow BCS at calving improved calf birth weights and weaning weights, whereas cow BCS change from calving until the start of the breeding season had no impact on calf performance. Together, the results described herein further emphasize the combined importance of precalving nutrition and calving BCS on cow and calf performance.

References

Carvalho, R. S., R. F. Cooke, B. I. Cappellozza, R. F. G. Peres, K. G. Pohler, and J. L. M. Vasconcelos. 2022. “Influence of Body Condition Score and Its Change after Parturition on Pregnancy Rates to Fixed-Timed Artificial Insemination in Bos indicus Beef Cows.” Anim. Reprod. Sci. 243: 107028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2022.107028

Cooke, R. F., C. L. Daigle, P. Moriel, S. B. Smith, L. O. Tedeschi, and J. M. B. Vendramini. 2020. “Cattle Adapted to Tropical and Subtropical Environments: Social, Nutritional, and Carcass Quality Considerations.” J. Anim. Sci. 98:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skaa014

Kunkle, W. E., and R. S. Sand. 1990. “Effect of Body Condition on Rebreeding.” Proc. 39th Annual Beef Cattle Short Course, UF/IFAS Department of Animal Sciences, pp. 154–165. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/IR/00/00/45/26/00001/AN00100.pdf

Moriel, P., E. Palmer, K. Harvey, and R. F. Cooke. 2021. “Improving Beef Cattle Performance through Developmental Programming.” Frontiers Anim. Sci. 2:728635. https://doi.org/10.3389/fanim.2021.728635

Moriel, P., M. Vedovatto, V. Izquierdo, E. A. Palmer, and J. M. B. Vendramini. 2024. “Maternal precalving supplementation of protein and energy and body condition score modulate the performance of Bos indicus-influenced cow-calf pairs.” Anim. Reprod. Sci. 262:107433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2024.107433

Mulliniks, J. T., S. H. Cox, M. E. Kemp, et al. 2012. “Relationship between Body Condition Score at Calving and Reproductive Performance in Young Postpartum Cows Grazing Native Range.” J. Anim. Sci. 90:2811–2817. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2011-4189

Vendramini, J. M. B., M. L. Silveira, and P. Moriel. 2023. “Resilience of Warm-Season (C4) Perennial Grasses under Challenging Environmental and Management Conditions.” Anim. Frontiers. 13:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfad038

Table 1. Body condition score (BCS; scale of 1 to 9) of Brangus cows that calved with below-optimal BCS (BCS < 5) or optimal or above-optimal BCS (BCS ≥ 5) and cows that lost, maintained, or gained BCS from calving until the start of the breeding season.

Table 2. Reproductive performance of Brangus cows according to their BCS at calving (BCS < 5 or BCS ≥ 5; scale of 1 to 9) and subsequent BCS change from calving until the start of the breeding season (lost, maintained, or gained BCS).1