The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Stomoxys calcitrans (L.), the stable fly (Figure 1), is a filth fly of worldwide medical and veterinary importance. Stable flies are obligate blood feeders and primarily attack cattle and horses for a blood meal. In the absence of these animal hosts, they will bite people and dogs. Consequently, stable flies also have an economic impact on Florida's tourism industry. Filth flies, including stable flies, are synanthropic, meaning that they exploit habitats and food sources created by human activities such as farming. Stable fly is the most universally accepted common name but there are many others used to refer to this pest, including dog fly, a colloquial term used to describe the fly’s use of canine hosts along the northwest beaches of Florida (King and Lenert 1936), biting house fly because of their similarity in appearance to house flies, and power-mower fly after a paper by Ware (1966).

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Synonymy

According to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS 2002), the following junior synonyms have been used for Stomoxys calcitrans:

Conops calcitrans Linnaeus, 1758

Musca occidentalis Walker, 1853

Stomoxis dira Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830

Stomoxis inimica Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830

Stomoxys cybira Walker, 1849

Stomoxys parasita Fabricius, 1781

Distribution

There are 18 known species in the genus Stomoxys. Of these 18 species Stomoxys calcitrans is the only species that is present worldwide and the only species that is synanthropic.

The stable fly is a globally recognized pest of livestock. In its normal agronomic environment, livestock facilities, the stable fly does not usually bother human beings. However, certain regions of the United States have conditions that result in stable flies attacking people. These regions include coastal New Jersey, the Lake Superior and Lake Michigan shorelines, Tennessee Valley Authority lakes, and along the Florida panhandle coast west to Louisiana. Within Florida, the area with the greatest problems with stable flies is west Florida. However, stable flies are numerous throughout the state.

Description

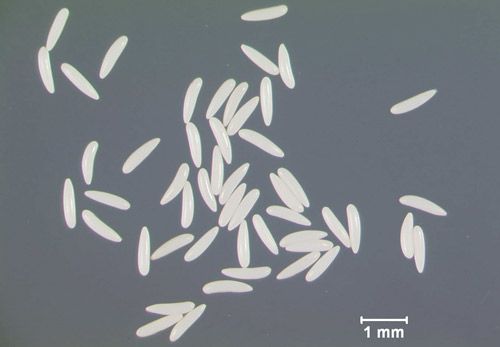

Eggs

Eggs are small, approximately 1 mm in length, white, and sausage-shaped (Figure 2). They are smooth and curved on one side and straight with a longitudinal groove on the other side.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Larvae

Immature stable flies are typical maggot-shaped (vermiform) fly larvae (Figure 3). A larva grows from the translucent first instar of about 1.25 mm to an 11–12 mm third instar larva that is pale yellow to creamy white with a mouth hook and two posterior spiracles.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Pupae

The third instar larval skin hardens to form a puparium that is reddish-brown and capsule-like. The larva then forms a pupa inside the puparium (Figure 4). The puparium is 4.5–6.0 mm in length and wider at the head end.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Adults

Stable fly adults are similar to the house fly in size and coloration. The length of an adult stable fly is typically 5–7 mm. The two species can be differentiated by examination of the abdomens and the mouthparts. Adult stable flies have seven circular spots in a checkerboard pattern on their abdomens and house flies have an unpatterned abdomen (Figure 5). Stable flies have elongated, bayonet-like mouthparts for piercing skin and feeding on blood (Figure 1), whereas house flies have sponging mouthparts for feeding on liquids.

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle

Stable flies develop in moist, decaying organic matter. The adult female lives for four to six weeks in the laboratory but around seven to ten days in the field, and during this time she lays multiple clutches of eggs. Each clutch may contain 60–130 eggs, which are laid in small groups within a suitable substrate. Each female fly may lay up to 800 eggs in her lifetime, with each clutch requiring a separate blood meal. Eggs hatch in 12 to 24 hours into first instar larvae, which feed and mature through three instars in 12 to 13 days at the optimum development site temperature of 27°C. Third instar larvae transform to pupae within the puparia. The adults develop inside and then emerge from the puparia. The average stable fly life cycle in the field ranges from 12–20 days depending on the environmental conditions but is usually around 28 days. Adults can fly within one hour post-emergence and will be ready to mate three to five days later. Once mated, the female will start to lay eggs five to eight days post-emergence.

Biology

Stable flies are unlike many other blood feeding fly species, in that both sexes feed on blood. In most other cases, the female feeds on blood to obtain protein for egg production and the male survives on sugar alone. Stable flies are diurnal, feeding on their hosts during the early morning and late afternoon in warm weather and in the middle of the day in cooler weather. When feeding, stable flies can fully engorge in five minutes if left undisturbed. After feeding and during hot periods of the day, they rest on the underside of vegetation, fences, and other structures near their hosts.

In Florida, the timing of peak stable fly abundance varies from year to year. Occasionally stable flies are active throughout the year or there are summer peaks, but most frequently peak populations occur in the spring. While in tropical and subtropical areas, such as Florida, there is a single peak in activity, in areas with dry summers and humid winters there may be two peaks in activity. In more northern states and countries, due to the harsh winter conditions, there is typically only one peak in the late summer. Stable fly abundance is closely linked to rainfall. Rainfall in weeks prior promote larval survival and create more larval development sites. Within the stable environment, stable fly distribution is not random, the flies avoid strong air currents and prefer humid areas.

Hosts

In the United States stable flies feed mainly on large ungulates such as cattle and horses. However, they are known to feed on goats, sheep, swine, donkeys, cats, dogs, and humans. On large animals, such as cattle and horses, the flies congregate on the legs, moving to other areas such as the belly and lower sides when populations are large (>25 flies per leg). On smaller animals, such as dogs, they feed around the ears due to the superficial blood vessels, and on the head and legs. Humans usually get bitten on the legs, behind the knees, and on the elbows.

Stable flies have great capacity for flight and can fly at speeds of 5 mph without wind. Studies have demonstrated their ability to disperse locally, particularly on farms or between farms, from their development sites to feeding sites and vice versa. A study of flies collected on equine facilities in Florida found that only 24.3% of the flies captured on horse farms had fed on horses; 64.6% had fed on cattle, 9.5% had fed on humans, and 1.6% had fed on dogs. The flies that had fed on cattle had travelled between 0.8 and 1.5 km after feeding on cattle to the equine facility. In Florida, stable flies have been recorded moving up to 225 km away from their farm sites to coastal sites.

Economic Importance

Stable flies attack people, pets, and agricultural animals throughout Florida to feed on their blood. Stable fly bites are extremely painful, and the flies are very persistent; they often ignore swatting, stamping, and other tactics used by animals trying to avoid bites.

The tourist industry is severely affected by large numbers of stable flies, especially on Florida's panhandle beaches. The flies are carried to the beach by northerly winds where they then bite visitors. Unlike many other blood feeding insect bites, on humans the bite site does not appear to get irritated and bites rarely result in allergic reactions.

Stable flies feeding on the ears of dogs and big cats in zoos can be a severe problem. The flies feed relentlessly, especially when the animals are confined, and the ears become bloody open sores and are slow to heal, leaving disfiguring scars.

The animal industries of the United States, including Florida, are affected by the stable fly. Livestock are weakened from continual irritation due to blood feeding flies. As a result of stable fly annoyance, animals exhibit avoidance behaviors such as stamping feet and switching tails. Animals in severely affected areas have been known to enter water bodies and stand with only their necks and heads exposed to escape the biting flies. Consequently, the animals become stressed and spend less time feeding. Swine, cattle, and horses all show reduced weight gains due to intensive fly feeding. Recent research has estimated that the annual cost of the stable fly to the United States livestock industry is $2.2 billion.

Management of stable flies to decrease numbers on animals reduces defensive behaviors and stress, which increases time spent grazing. Therefore, stable fly management is important for protecting animal health and welfare in the short-term but the resulting increases on weight gain and milk production will have direct impacts on the productivity of livestock.

Stable flies feed on the blood of animals and are therefore potential vectors of blood-borne zoonotic diseases. Their ability to transmit the pathogens that cause diseases such as anthrax, equine infectious anemia (EIA), and anaplasmosis to animals has been documented. Stable fly bite wounds also can become secondarily infected by opportunistic pathogens.

Management

Stable flies observed on their animal host are usually feeding, as they leave the host immediately after feeding is completed. Consequently, infestations in the early stages may not be noticed until the situation is well above the threshold where economic damage is inevitable. Monitoring is important for determining when management is necessary to prevent an outbreak situation. In the field, monitoring of stable fly numbers is done by counting flies on cattle (Figure 6). Counts should be done on both front legs of at least 15 animals. The threshold is 10 flies per animal. If stable fly numbers are greater than the threshold, then reductions in animal performance that are considered economically damaging are likely to occur. Stable fly numbers greater than the threshold suggests the presence of a productive local developmental site. Counts on horses are not as reliable as horses are more sensitive to the bites than cattle and tend to disturb the flies more frequently. On horse farms, sticky traps can be used for effective monitoring.

Credit: Phillip Kaufman, UF/IFAS

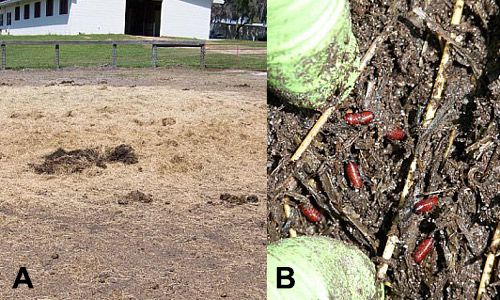

If monitoring reveals that the local stable fly population is greater than the threshold of 10 flies per animal then management of potential development sites should be implemented (Figure 7). The preferred habitat of stable flies is hay ring feeding sites; the residues of feeding hay in fields provides a highly productive larval development site. However, development may occur in any type of moist, decaying organic matter such as: silage, crop residue, hay, grain, manure, and soiled animal bedding. To reduce fly development, spread crop residues and animal manures thinly so they dry quickly, clean up spilled food, and rotate hay feeding areas in fields. For animals housed in stalls, carefully choose bedding material and remove waste daily. Wood shavings are better than straw or hay because they do not decompose or become compacted as quickly once soiled. Decomposing bedding provides prime stable fly developmental habitat. Reducing decomposing organic matter around animal facilities also will reduce the presence of other localized fly problems for the health and safety of your animals, your neighbors' animals, and the local community.

Credit: Phillip Kaufman, UF/IFAS

There may be instances where removal of larval development sites is not enough to control stable fly numbers below the threshold (ten flies per animal). In these situations, an integrated pest management approach should be adopted by selecting suitable tools from the biological, mechanical, and chemical control options available. Biological control, in the form of commercially available parasitoid wasps, can be used to target stable fly pupae and thus increase parasitism levels by supporting naturally present parasitoids (Figure 8). Entomopathogenic fungi and nematodes also have been demonstrated to have the potential for use against stable flies. Flies treated with fungi die in 5-7 days and the fungus has sub-lethal effects that limit the fly's fitness. Alternative control measures include the use of traps (e.g., Alsynite traps; Figure 9, or Knight stick traps), insecticide treated targets, and insecticide treatment of stable fly resting sites or cattle. Insect repellents may also be used to provide some relief to humans and other animals. For example, natural repellents containing citronella are often used on horses. Judicious use of insecticides is warranted as resistance has been documented in Florida populations of stable flies (Pitzer et al. 2010).

Credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Phillip Kaufman, UF/IFAS

Selected References

Broce AB. 1988. An improved Alsynite trap for stable flies Stomoxys calcitrans (Diptera: Muscidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 25: 406-409.

Campbell JB, Skoda SR, Berkebile DR, Boxler DJ, Thomas GD, Adams DC, Davis R. 2001. Effects of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) on weight gains of grazing yearling cattle. Journal of Economic Entomology 94: 780-783.

Catangui MA, Campbell JB, Thomas GD, Boxler DJ. 1995. Average daily gains of Brahman-crossbred and English x exotic feeder heifers during long-term exposure to stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 88: 1349-1352.

Catangui MA, Campbell JB, Thomas GD, Boxler DJ. 1997. Calculating economic injury levels for stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) on feeder heifers. Journal of Economic Entomology 90: 6-10.

Cilek JE. 2002. Attractiveness of beach ball decoys to adult Stomoxys calcitrans (Diptera: Muscidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 39: 127-129.

Foil L, Hogsette JA. 1994. Biology and control of tabanids, stable flies and horn flies. Revue Scientifique et Technique de l'Office International des Epizooties 13: 1125-1158.

Hogsette JA, Ruff JP. 1985. Stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae) migration in northwest Florida. Environmental Entomology 14: 170-175.

Hogsette JA, Ruff JP, Jones CJ. 1989. Dispersal of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae). Miscellaneous Publications of the Entomological Society of America 74: 23-32.

Hogsette JA. 1990. Comparative attraction of four different fiberglass traps to various age and sex classes of stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae) adults. Journal of Economic Entomology 83: 883-886.

Hogsette JA, Ose GA. 2017. Improved capture of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) by placement of knight stick sticky traps protected by electric fence inside animal exhibit yards at the Smithsonian's National Zoological Park. Zoo Biology 36: 382-386.

Hogsette JA, Foil LD. 2018. Blue and black cloth targets: Effects of size, shape and color on stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae). Journal of Economical Entomology 111: 974-979.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System (IT IS). 2002. Stomoxys calcitrans TSN 150287. Integrated Taxonomic Information System on-line database, http://www.itis.gov. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=150287 (31 October 2022).

Jones CJ, Hogsette JA, Patterson RS, Milne DE, Propp GD, Milio JF, Rickard LG, Ruff JP. 1991. Origin of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) on west Florida beaches: Electrophoretic analysis of dispersal. Journal of Medical Entomology 28: 787-795.

King WV, Lenert LG. 1936. Outbreaks of Stomoxys calcitrans (“dog flies”) along Florida’s Northwest coast. Florida Entomologist 19(3): 33-42.

LaBrecque GC, Meifert DW, Weidhaas DE. 1972. Dynamics of house fly and stable fly populations. Florida Entomologist 55: 101-106.

Lysyk TJ. 1993. Seasonal abundance of stable flies and house flies (Diptera: Muscidae) in dairies in Alberta, Canada. Journal of Medical Entomology 30:888-895.

Machtinger ET, Geden CJ, Kaufman PE, House AM. 2015. Use of pupal parasitoids as biological control agents of filth flies on equine facilities. Journal of Integrated Pest Management. 6:16 DOI:10.1093/jipm/pmv015.

Machtinger ET, Leppla NC, Hogsette JA. 2016. House and stable fly seasonal abundance, larval development substrates, and natural parasitism on small equine farms in Florida. Neotropical Entomology 45: 433-440.

Marcon PCRG, Thomas GD, Siegfried BD, Campbell JB. 1997. Susceptibility of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) from southeastern Nebraska beef cattle feedlots to selected insecticides and comparison of 3 bioassay techniques. Journal of Economic Entomology 90: 293-298.

Moon RD. 2002. Muscoid flies (Muscidae), pp. 45-65. In GR Mullen and LA Durden (eds.), Medical and Veterinary Entomology, vol. 2. Elsevier, San Diego, CA.

Pickens LG, Schmidtmann ET, Miller RW. 1994. How to control house and stable flies without using pesticides, pp. 1-14. USDA, Washington, DC.

Pitzer JB, Kaufman PE, Tenbroeck SH. 2010. Assessing permethrin resistance in the stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae) in Florida by using laboratory selections and field evaluations. Journal of Economic Entomology. 103: 2258-2263.

Pitzer JB, Kaufman PE, TenBroeck SH, Maruniak JE. 2011. Host blood meal identification by multiplex polymerase chain reaction for dispersal evidence of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) between livestock facilities. Journal of Medical Entomology 48: 53-60.

Rochon K, Lysyk TJ, Selinger LB. 2004. Persistence of Escherichia coli in immature house fly and stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae) in relation to larval growth and survival. Journal of Medical Entomology 41: 1082-1089.

Semelbauer M, Mangová B, Barta M, Kozánek M. 2018. The factors influencing seasonal dynamics and spatial distribution of stable fly Stomoxys calcitrans (Diptera, Muscidae) within stables. Insects 9: 142 DOI: 10.3390/insects9040142.

Taylor DB, Moon RD, Mark DR. 2012. Economic impact of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) on dairy and beef cattle production. Journal of Medical Entomology 49: 198-209.

Weeks ENI, Machtinger ET, Gezan SA, Kaufman PE, Geden CJ. 2017. Effects of four commercial fungal formulations on mortality and sporulation in house flies (Musca domestica) and stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans). Medical and Veterinary Entomology 31: 15-22.

Weeks ENI, Machtinger ET, Leemon D, Geden CJ. 2018. Biological control of livestock pests: entomopathogens. In C Garros, J Bouyer, W Takken, RC Smallegange (eds.), Prevention and Control of Pests and Vector-borne Diseases in the Livestock Industry. Ecology and Control of Vector-Borne Diseases Volume 5. Wageningen Academic Publishers, The Netherlands.

Woolley CE, Lachance S, DeVries TJ, Bergeron R. 2018. Behavioral and physiological responses to pest flies in pastured dairy cows treated with a natural repellent. Applied Animal Behavioral Science 207: 1-7.

Wright RE. 1985. Arthropod pests of beef cattle on pastures and range land, pp. 191-206. In RE Williams, RD Hall, AB Broce and PJ Scholl (eds.), Livestock Entomology. Wiley, New York.