The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The tomato pinworm is a small, microlepidopteran moth that is often confused with closely related species, which have similar habits. Apparently, much of the damage to tomatoes attributed to the eggplant leafminer (Gnorimoschema glochinella Zeller) in Mexico and California during the early 1920s was actually inflicted by the tomato pinworm (Morrill 1925). It persisted in the literature as the eggplant leafminer until redescribed as a new species (Busck 1928) collected from tomatoes. It was later synonymized with Eucatoptus lycopersicella Walshingham. Capps (1946) provided a key, with descriptions, that defines the species and permits identification of larvae with which it might be confused.

Distribution

Tomato pinworms are found in the warm agricultural areas of Mexico, California, Texas, Hawaii, Cuba, Haiti, and the Bahamas. Also, they have been reported from greenhouses in Delaware, Mississippi, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Fields near greenhouses may become infested, but the species does not overwinter out of doors in colder regions (Thomas 1933). In Florida, it is common in tomato-producing areas south of Tampa along the west coast and from Ft. Pierce south along the east coast.

Life History

The developmental time for each stage from egg to adult is shown in the table below (Elmore and Howland 1943). Eggs are laid singly or grouped in twos and threes on the host-plant foliage. The eggs are opaque, pale yellow when laid, but turn orange before hatching. The first instar larvae spin a tent of silk over themselves and tunnel into the leaf. Further feeding results in a blotch-like mine usually on the same leaf. The third and fourth larval stages feed from within tied leaves, folded portions of a leaf, or enter stems or fruits. Mature larvae abandon the host and form a loose pupal cell of sand grains near the soil surface. The adult emerges from this pupal cell two to four weeks later. Although the life cycle is lengthy, generations overlap and infestations quickly mount to damaging proportions. Seven or eight generations or more per year can be expected.

Credit: David J. Schuster, University of Florida

Credit: James Castner, University of Florida

Credit: University of Florida

Hosts

Plants of the nightshade family, Solanaceae, are the preferred hosts of pinworms. Tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum L., is infested most commonly, but eggplant, Solanum melongena L. var esculentum Nees, and potatoes, Solanum tuberosum L. also are attacked. Weeds such as S. carolinense L., S. xanthii Gray, and S. umbelliferum Esch. have been suitable hosts. Tomato, potato, eggplant, and a weed, S. bahamese L., are recorded hosts in Florida.

Economic Importance

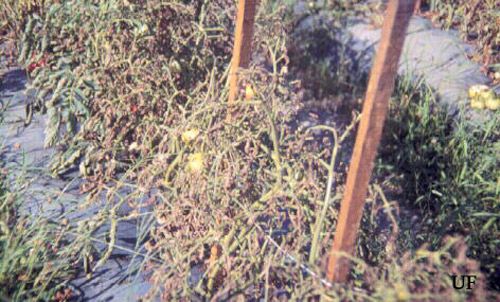

Damage to tomatoes results from the feeding of larvae on leaves, stems and fruit. Initial injury is slight and appears as a small leaf mine. Later injury includes leaf folding and leaf tying. Mature larvae may abandon the leaf and bore into the fruit leaving a small "pin" size hole. Secondary damage results when plant tissues become infected by pathogens and the plant dies or the fruit rots. Approximately 60 to 80 percent of tomato fruits may become infested in a single season (Elmore and Howland 1943).

Credit: David J. Schuster, University of Florida

Credit: David J. Schuster, University of Florida

Credit: J. L. Castner, University of Florida

Credit: David J. Schuster, University of Florida

Credit: Van Waddill, University of Florida

Management

Several sanitary measures should be followed because infestations often result from shipment of pinworms in picking containers, crates, infested fruit or seedlings, and from populations perpetuated on plants left in fields after harvest or left in seed flats or compost heaps (Poe 1973). The precautions include use of transplants that are free of eggs and larvae when set in the field, and the destruction of all plant debris and fields after harvest. Populations may be controlled early during the first or second larval stages with several recommended insecticides (Poe 1973); however, third or fourth instars are protected by leaf folds or fruit, making the control of older infestations difficult. Consequently, chemical control is contingent upon frequent and accurate observations of fields for pinworm mines.

Selected References

Busck, A. 1928. Phthorimaea lycopersicella, N. sp. (Family: Gelechiidae) a leaf feeder on tomato (Lep.). Hawaiian Entomology Society Proceedings 7: 171–176.

Capps HW. 1946. Description of the larvae of Keiferia penicula Heim., with a key to the larvae of related species attacking eggplant, potato and tomato in the United States. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 39: 561–563.

Elmore JC and Howland AF. 1943. Life history and control of the tomato pinworm. USDA Technical Bulletin 841. 30 p.

Poe SL. 1973. The tomato pinworm in Florida. UF/IFAS, AREC Research Report GC1973–2. 5 pp.

Thomas CA. 1933. Observations on the tomato pinworm (Gnorimoschema lycopersicella Busck) and the eggplant leafminer (G. glochinella Zeller) in Pennsylvania. Journal of Economic Entomology 26: 137–143.