The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Eurhinus magnificus Gyllenhal was first reported in Florida in 2002 when a single specimen was found in an ornamental nursery in Broward County (Feiber 2002). It was collected again in 2003 near Homestead, Miami-Dade County, and was also intercepted in a shipment of bananas from Costa Rica (Fowler 2004). It is likely that this weevil was inadvertently imported into Florida through trade in live plants or plant products. In 2005, all life stages of E. magnificus were collected repeatedly in both Broward and Miami-Dade Counties from the host plant Cissus verticillata (L.) Nicolson & Jarvis (Vitaceae).

C. verticillata, also known by the common names of possum grape vine, princess vine, and season vine, supports the entire life cycle of E. magnificus. Eggs are laid within the stem where larvae hatch and begin to feed. The larvae complete five instars, within a gall formed at the location of oviposition, before pupating. Adults emerge from the host plant gall to feed on C. verticillata, mate and oviposit.

It is still to be determined if this new weevil will cause damage in the grape cultivars (Vitis spp.) in the grape growing regions of Florida.

Synonymy

Eurhinus magnificus is a member of the Curculionidae-Baridinae. The original spelling of the genus, Eurhin Illiger 1807, was suppressed by the plenary power of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (Melville 1985), thereby following the arguments of Zimmerman and Thompson (1983) for resolving a nomenclatural conflict between two homonymously used family-group names.

Distribution

The genus includes 23 species that are widely distributed. Eurhinus magnificus occurs in Belize, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Panama (Vaurie 1982, Schall 2002). In 2005, E. magnificus was abundant and successfully reproducing in various habitats where the host plant C. verticillata was present across Miami-Dade and Broward Counties. After first being reported in Florida in 2002, it appears to be established and flourishing in the southeast region of the state.

Description

Adult

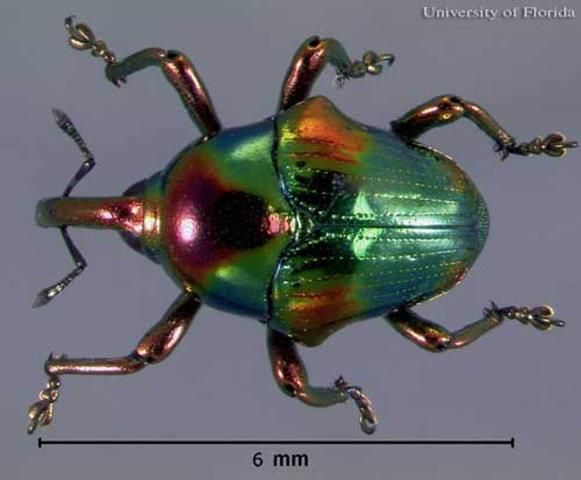

This insect is a robust weevil similar in body form to other Eurhinus weevils (Bondar 1948) and, like many of the other species, E. magnificus adults are brilliantly colored. The entire body is a vibrant, metallic blue-green with areas of metallic red-copper on the humeri and apex of the elytra and on the pronotum, rostrum, and legs. The mean dimensions of the adult are 5.66 mm long by 3.71 mm wide (Ulmer et al. 2007).

Credit: Bryan J. Ulmer, University of Florida

Credit: Huang Ta-I, University of Florida

Egg

The egg is milky beige and a mean of 1.24 mm long by 0.72 mm wide (Ulmer et al. 2007).

Credit: Bryan J. Ulmer, University of Florida

Credit: Bryan J. Ulmer, University of Florida

Larva

Body stout, curved, greatest width near middle, tapered at both ends. The mean head capsule width of a fifth instar larva is 1.6 mm. A full description of the larva and pupa can be found in Ulmer et al. 2007.

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

Pupa

Stout in appearance, with a mean length of 5.66 mm by 3.71mm wide.

Credit: Bryan J. Ulmer, University of Florida

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

Credit: Bryan J. Ulmer, University of Florida

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

Biology

Adults feed on the outer layers of host plant stems and also within cavities created in the stems and the leaf petioles. Some feeding also occurs on leaf blades at the portion of the leaf directly around the attachment point of the petiole. Females oviposit in young parts of the stem (mean diameter = 2.3 mm) by creating a cavity with their rostrum and depositing a single egg. One or two eggs are laid within a single host plant internode. Gall formation becomes detectable by the first to third instar larva. The largest diameter of the gall is at the pupal stage, at this stage the mean stem size is 4.2 mm and the mean gall size was 9.2 mm.

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

Credit: Bryan J. Ulmer, University of Florida

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

A single specimen of E. magnificus, reared in a greenhouse in Homestead, Florida, required approximately 83 days to develop from egg to adult during the coldest part of the year. It is likely that the development time of E. magnificus would be greatly reduced during the summer months. The presence of adults in the field and larval development observed during winter indicate that E. magnificus is capable of reproducing throughout the year in south Florida. Adults emerging from field collected galls survived nine to 47 days (mean 32 days) from the time of emergence under laboratory conditions (Ulmer et al. 2007).

Host Plants and Damage

Like other members of the genus, E. magnificus larvae induce galls on the stems of Cissus spp. (Vitaceae) (Bondar 1948). Vernonia, Andira and Mikania spp. have also been suggested as host plants (Silva et al. 1968, Vaurie 1982). However, the only verified host plant of E. magnificus in Florida is C. verticillata.

Florida contains native species of all four genera which are also represented by species occurring over a wide range in the United States (Fowler 2004, USDA 2006). C. verticillata is widely distributed in the Caribbean, Central and South America, and Mexico (Lombardi 2000). It also is considered native to Florida in the United States (USDA 2005). Though C. verticillata is sometimes planted as an ornamental, it is a prolific perennial vine that is generally considered a weedy species when occurring with various ornamental and fruit crops in south Florida (Futch and Hall 2003).

In Trinidad and Tobago, C. verticillata is used for medicinal purposes against urinary problems (Lans 2006). A single adult was also found on pigmy palm, Phoenix robelenii O'Brien (Arecaceae), and one was collected from avocado, Persea americana Mill. (Lauraceae), foliage. However, no evidence of feeding or oviposition was observed on these two plants and it is likely that the collections were incidental and they are not true host plants.

In general, C. verticillata appear healthy and actively growing beyond the point of gall formation. However, the development of E. magnificus within the stem causes a significant malformation and often has an obvious negative impact on the host plant. Occasionally the gall and resulting damage coupled with environmental conditions results in severing the stem.

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

Credit: Rita E. Duncan, University of Florida

Eurhinus magnificus is not known to be a pest of commercial grapes and is not considered a threat to attack Vitis spp. (Fowler 2004). However, in a preliminary study Ulmer et al (2007) showed three of four cultivars tested were attacked by adult weevils in a no-choice situation resulting in feeding damage and galls. No larval development was apparent on any of the grape species tested. It is conceivable that this weevil could develop on other grape cultivars under different conditions. Additional studies to investigate a wide range of grape cultivars varying in physical and chemical characteristics should be undertaken before eliminating Vitis spp. as suitable host plants.

The impact of the weevil on C. verticillata and on other potential hosts, such as Vernonia spp. and Vitis spp., is not discernible at this early stage of colonization but necessitates future research. Further work is also required to better understand the population biology of E. magnificus and to establish its potential for range expansion in the United States.

Management

Successful development of E. magnificus in the field appears to be significantly reduced by predation and fungal agents. However, an examination of approximately 200 specimens of E. magnificus revealed no evidence of parasitism for any life stage. There are no records of parasitism for E. magnificus in its native range. Capitonius tricolorvalvus Ent (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) was reared from stem galls of C. verticillata in Costa Rica, the host was not identified but presumed to be a beetle (Ent and Shaw 1999). Further sampling is needed to establish the parasitoid fauna, or lack of, associated with this weevil in Florida and its native range.

Selected References

Bondar G. 1948. Notas entomologicas da Baía XX. Rev. Entomol., Rio de J. 9 (1-2): 1–54.

Ent LJ van der, Shaw SR. 1999. A new species of Capitonius (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) from Costa Rica with rearing records. Pan-Pacific Entomologist 75: 112–120.

Feiber D. (2002). Plant Industry Update. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. http://www.doacs.state.fl.us/pi/images/F02newsletter.pdf (29 August 2007).

Fowler L. 2004. Eurhin magnificus Gyllenhal: Weevil Coleoptera/Curculionidae. New Pest Advisory Group (NPAG). Plant Epidemiology Risk Analysis Laboratory, Center for Plant Health Science and Technology. Report 040305: 1–2.

Futch SH, Hall DW. (2003). Identification of vine weeds in Florida citrus. EDIS. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/HS185 (October 2023).

Lans CA. 2006. Ethnomedicines used in Trinidad and Tobago for urinary problems and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2:45.

Lombardi JA. 2000. Vitaceae: Generos Ampelocissus, Ampelopsis, e Cissus. Flora Neotropica Monograph. 80: 200.

Schall R. 2002. Eurhin magnificus – A Central American weevil. New Pest Advisory Group (NPAG) Data. p.9. In L. Fowler, 2004.

Silva A, d'Araújo e G, Rory Gonçalves C, Monteiro Galvão D, Lobo Gonçalves AJ, Gomes J, do Nascimento Silva M, de Simoni L. 1968. Quarto catálogo dos insetos que vivem nas plantas do Brasil. Seus parasitos e predatores, v. I (2).– Ministério da Agricultura, Rio de J., III-XXVI, 622p.

United States Department of Agriculture. (2005). Cissus verticillata (L.) Nicolson & C.E. Jarvis. Germplasm Resources Information Network. https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxon/taxonomydetail?id=310369 (October 2023).

United States Department of Agriculture. (2006). Plants Database. Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://plants.usda.gov/home (October 2023)

Ulmer BJ, Duncan RE, Prena J, Peña JE. 2007. Life History and Larval Morphology of Eurhinus magnificus Gyllenhal (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), a New Weevil to the United States. Neotropical Entomology 36: 383–390

Vaurie P. 1982. Revision of Neotropical Eurhin (Coleoptera: Curculionidae, Baridinae). Novitates 2753: 1–44.

Zimmerman EC, Thompson RT. 1983. On family group names based upon Eurhin, Eurhinus and Eurhynchus (Coleoptera). Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 40: 45–52.