The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Psorophora ciliata (Fabricius) is a large mosquito (Cutwa and O'Meara 2005) that has developed an outsized reputation because of its relatively intimidating heft and persistent biting behavior (Gladney and Turner 1969), including anecdotal historical accounts of its legendary aggressiveness (Wallis and Whitman 1971) and 'frightening appearance' (King et al. 1960). The 'gallinipper' or 'shaggy-legged gallinipper' was used as a common name for Psorophora ciliata in various published reports (Ross 1947; King et al. 1960; Breeland et al. 1961; Goddard et al. 2009). The term was mentioned much earlier by Flanery (1897) describing the mosquito as 'the little zebra-legged thing—the shyest, slyest, meanest, and most venomous of them all' [sic] but did not specify what species it was. The word gallinipper originated as a vernacular term in the southeastern region of the United States referring to 'a large mosquito or other insect that has a painful bite or sting' and has appeared in folk tales, traditional minstrel songs, and a blues song referencing a large mosquito with a 'fearsome bite' (McCann 2006). However, the Entomological Society of America has not recognized 'gallinipper' or 'shaggy-legged gallinipper' as an official common name for Psorophora ciliata (ESA 2012). Of special interest, Psorophora ciliata is one of the few mosquito species whose larvae are predacious to other mosquito larvae (Howard et al. 1917; Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

For additional information on mosquitoes, see https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN652.

Synonymy

Psorophora ciliata (Fabricius 1794)

Culex ciliata Fabricius (1794)

Culex conterrens Walker (1856)

Culex molestus Weidemann (1820)

Culex rubidus Robineau-Desvoidy (1827)

Psorophora boscii Robineau-Desvoidy (1827)

Psorophora ctites Dyar (1918)

(From ITIS 2011)

Distribution

Psorophora ciliata usually is associated with other floodwater mosquitoes, including many species from the Aedes genera (Breeland et al. 1961), and has a wide distribution in the New World. Floodwater mosquitoes often lay their eggs in low-lying areas with damp soil and grassy overgrowth. When these areas flood following a dry period, the eggs hatch, often producing very large numbers of adult mosquitoes.

Psorophora ciliata occurs east of the Continental Divide (Howard et al. 1917; Darsie and Ward 2005) from the southern portions of Ontario and Quebec (Wood et al. 1979; Foss and Deyrup 2007) to as far south as Argentina (Campos et al. 2004). A new record has been reported recently from the highlands of Colombia (Barreto et al. 1996) but still east of the Continental Divide. There is no record of Psorophora ciliata in the Old World.

Credit: Marcos Gomez based on Darsie and Ward (2005)

Description

Adults

Psorophora ciliata is one of the largest known mosquitoes in the US (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955) with female adults having a wing length of 6.0–6.7 mm (Means 1987). The size alone is a distinguishing characteristic (Cutwa and O'Meara 2005) with only Toxorhynchites rutilus rutilus (Coquillett), Toxorhynchites rutilus septentrionalis (Dyar and Knab), and Psorophora howardii Coquillett being of similar or larger size (King et al. 1960). Psorophora howardii is similar morphologically and has the same distribution (Darsie and Ward 2005) in the southeastern United States, but is encountered less frequently (King et al. 1960; Breeland et al. 1961). Other distinguishing characteristics include a longitudinal band of yellow scales on the thorax, yellow scales forming a band on the proboscis, and the 'shaggy' or 'feathery' pronounced dark scales on the hindleg segments (Darsie and War 2005), hence the unofficial common name of 'shaggy-legged' or 'feather-legged gallinipper.'

Credit: Sean McCann

Credit: Darrin O'Brien

Credit: Michelle Cutwa-Francis, UF/IFAS

Eggs

Psorophora ciliata eggs are 'elongate ovoid' in shape measuring about 0.8 mm in length and 0.4 mm in diameter at their widest girth, and are among the longest and thickest measured among the Psorophora species. Their outer surface is white when first deposited but later turns black, with spine-like projections directed towards the anterior (Horsfall et al. 1952). Comparable with other floodwater and container-breeding mosquitoes, Psorophora ciliata eggs can stand long periods of desiccation and usually are found in areas where rain collects (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955).

Larvae

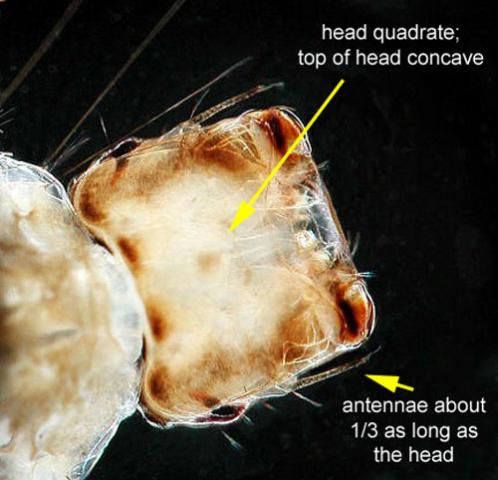

Similar to adults, Psorophora ciliata larvae are larger than most mosquito larvae. Another distinguishing characteristic of fourth instar larvae is a square-shaped head with the dorsal side of the head curved inwards (Cutwa and O'Meara 2005; Darsie and Ward 2005). The mouthparts of the larvae have evolved to hold and grasp prey (Shalaby 1957).

Credit: Ary Farajollahi, Mercer County Mosquito Control, NJ

Credit: Michelle Cutwa-Francis from Cutwa and O'Meara (2005)

Pupae

The pupae of Psorophora ciliata are very difficult to distinguish from other mosquito pupae and rarely are used for mosquito identification, but the size alone should be an indication of species potential. The pupae of Toxorhynchites species and Psorophora howardii, also relatively large mosquitoes that could be mistaken for Psorophora ciliata.

Credit: Michelle Cutwa-Francis, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle

Psorophora ciliata overwinters in the egg stage (Breeland et al. 1961; Wallis and Whitman 1971) and may not hatch until mid-summer or after the first rainfall event of the season (Wood et al. 1979). The first instar larvae are filter-feeders, whereas the second, third, and fourth instar larvae are predacious to aquatic invertebrates, including other mosquito larvae (Shalaby 1957). Psorophora ciliata larvae also have been reported to be cannibalistic (Howard et al. 1917) and have been documented feeding on tadpoles (Breeland et al. 1961). Adults lay their eggs in habitats used by Aedes and other Psorophora species in floodwater environments (Carpenter and LaCasse 1955; Horsfall et al. 1952; King et al. 1960). Larvae have a very rapid development in laboratory settings, with adults emerging only six days after eggs hatch (Breeland and Pickard 1963).

Medical and Veterinary Importance

Psorophora ciliata are primarily mammalian blood-feeders. An extensive study of Florida mosquitoes by Edman (1971) demonstrated that more than half of the blood meals detected from this species were from ruminants, and the rest from armadillos, raccoons, and rabbits. This mosquito will feed readily on humans and can be annoying in larger numbers (Howard et al. 1917). However, Wallis and Whitman (1971) conveyed that its status as a pest species may not be that important due to its relative rarity compared to other pest mosquito species.

Psorophora ciliata have tested positive for the presence of Eastern equine encephalitis virus (Chamberlain et al. 1954), Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (Sudia et al. 1975), Western equine encephalitis virus (Mitchell et al. 1987), Tensaw virus (Wozniak et al. 2001), and West Nile virus (Chow et al. 2002; CDC 2011). However, there are no confirmative studies indicating that Psorophora ciliata is a bridge vector for those viruses, nor any follow-up published research documenting that this species is a competent vector of pathogens of medical and veterinary importance.

Management

Limited published surveillance or management studies have been found specifically for this mosquito. In a study to determine attraction to different artificial lights, Psorophora ciliata was shown to be attracted to certain incandescent blue light compared to other colors (Ali et al. 1989). Because this species is associated with other floodwater mosquitoes, the management and control of such species should lead to the reduction of Psorophora ciliata populations.

The proclivity of Psorophora ciliata larvae to consume other mosquito larvae, including pestiferous species such as Aedes albifasciatus (Macquart) (Campos et al. 2004), Aedes vexans (Meigen), and other floodwater mosquitoes (Breeland et al. 1961), has led to suggestions of using this species as biological control agent of pest and vector mosquitoes (Howard et al. 1917; Gladney and Turner 1969). However, King et al. (1960) argued that Psorophora ciliata larvae do not occur in large enough numbers to be effective in controlling overall pest mosquito populations. Additionally, the point is moot because of the pestiferous nature of adult females effectively undermining any potential benefits of using the larvae as a biological control agent (Holck 1988; Mercer et al. 2005).

Selected References

Ali A, Nayar JK, Knight JW, Stanley BH. 1989. Attraction of Florida mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to artificial light in the field. Annual Conference of the California Mosquito and Vector Control Association 57: 82–88.

Barreto M, Burbano ME, Suarez M, Barreto P. 1996. Psorophora ciliata y otros mosquitos (Diptera: Culicidae) en Yolombó, Antioquia, Colombia. Colombia Médica 27: 62–65.

Bentley MT, Kaufman PE, Kline DL, Hogsette JA. 2009. Response of adult mosquitoes to light-emitting diodes placed in resting boxes and in the field. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 25: 285–291.

Breeland SG, Snow WE, Pickard E. 1961. Mosquitoes of the Tennessee Valley. Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science 36: 249–319.

Breeland SG, Pickard E. 1963. Life history studies on artificially produced broods of floodwater mosquitoes in the Tennessee Valley. Mosquito News 23: 75–85.

Campos RE, Fernandez LA, Sy VE. 2004. Study of the insects associated with the floodwater mosquito Ochlerotatus albifasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) and their possible predators in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Hydrobiologia 524: 91–102.

Carpenter SJ, LaCasse WJ. 1955. Mosquitoes of North America (North of Mexico). University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. 488 pp.

CDC. (2011). Mosquito species producing WNV positive by year. (Last modified 30 April 2009). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. (24 August 2012)

Chamberlain RW, Sikes RK, Nelson DB, Sudia WD. 1954. Studies on the North American arthropod-borne encephalitides. VI. Quantitative determinations of virus-vector relationships. American Journal of Hygiene 60: 278–285.

Chow CC, Montgomery SP, O'Leary DR, Nasci RS, Campbell GL, Kipp AM, Lehman JA, Olson K, Collins P, Marfin AA. 2002. Provisional surveillance summary of the West Nile virus epidemic - United States, January - November 2002. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 51: 1129–1133.

Cutwa MM, O'Meara GF. 2005. Photographic guide to common mosquitoes of Florida. Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Vero Beach FL. 83 pp.

Darsie RF, Ward RA. 2005. Identification and Geographical Distribution of the Mosquitoes of North America, North of Mexico, 1st Edition. University Press of Florida. Gainesville, FL. 400 pp.

Edman JD. 1971. Host-feeding patterns of Florida mosquitoes I. Aedes, Coquillettidia, Mansonia and Psorophora. Journal of Medical Entomology 8: 687–695.

ESA. (2012). Common Names of Insects Database, Family: Culicidae. Entomological Society of America. Lanham, MD. (24 August 2012)

Flanery D. 1897. Immunity from mosquito bites. Nature 56:53.

Foss KA, Deyrup LD. 2007. New record of Psorophora ciliata in Maine, United States. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 23: 476–477.

Gladney WJ, Turner Jr EC. 1969. The insects of Virginia: No. 2: Mosquitoes of Virginia (Diptera: Culicidae). Research Division Bulletin 49, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Blacksburg, VA. 28 pp.

Goddard J, Varnado WC, Harrison BA. 2009. An annotated list of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of Mississippi. Journal of Vector Ecology 35: 79–88.

Holck AR. 1988. Current status of the use of predators, pathogens and parasites for the control of mosquitoes. Florida Entomologist 71: 537–546.

Horsfall WR, Miles RC, Sokatch JT. 1952. Eggs of floodwater mosquitoes. I. Species of Psorophora (Diptera: Culicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 45: 618–624.

Howard LO, Dyar HG, Knab F. 1917. The mosquitoes of North and Central America and the West Indies. Volume Four, Systematic Description (in two parts) Part II. The Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC. 550 pp.

ITIS. (2011). Psorophora ciliata (Fabricius, 1794). Integrated Taxonomic Information System, United States Geological Survey, Reston, VA. (24 August 2012)

King WV, Bradley GH, Smith CN, McDuffie WC. 1960. A handbook of the mosquitoes of the Southeastern United States. Agricultural Handbook No. 173. United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. 192 pp.

McCann SM. (2006). Gallinipper? - Psorophora howardii. Bug Guide, Iowa State University, Ames, IA. (24 August 2012)

Means RG. 1987. Mosquitoes of New York. Part II. Genera of Culicidae other than Aedes occurring in New York. New York State Museum Bulletin 430b. The State Education Department, The University of the State of New York, Albany, NY. 180 pp.

Mercer DR, Sheeley SL, Brown EJ. 2005. Mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) development within microhabitats of an Iowa wetland. Journal of Medical Entomology 42: 685–693.

Mitchell CJ, Monath TP, Sabattini MS, Daffne JF, Cropp CB, Calisher CH, Darsie Jr RF, Jakob WL. 1987. Arbovirus isolations from mosquitoes collected during and after the 1982-1983 epizootic of western equine encephalitis in Argentina. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 36: 107–113.

Ross HH. 1947. The mosquitoes of Illinois (Diptera, Culicidae). Bulletin of the Illinois Natural History Survey 24: 1–96.

Shalaby AM. 1957. The mouth parts of the larval instars of Psorophora ciliata (Fabricius). Bulletin of the Entomological Society of Egypt 41: 429–455.

Sudia WD, Newhouse VF, Beadle ID, Miller DL, Johnston Jr JG, Young R. Calisher CH, Maness K. 1975. Epidemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis in North America in 1971: Vector studies. American Journal of Epidemiology 101: 17–35.

Unlu I, Kramer WL, Roy AF, Foil LD. 2010. Detection of West Nile virus RNA in mosquitoes and identification of blood meals collected at alligator farms in Louisiana. Journal of Medical Entomology 47: 625–633.

Wagner VE, Efford, AC, Williams RL, Kirby JS, Grogan Jr WL. 2007. Mosquitoes associated with U.S. Department of Agriculture wetlands on Maryland's Delmarva Peninsula. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 23: 346–350.

Wallis RC, Whitman L. 1971. New collection records of Psorophora ciliata (Fabricius), Psorophora ferox (Humboldt) and Anopheles earlei Vargas in Connecticut (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 8: 336–337.

Wozniak A, Dowda HE, Tolson MW, Karabatsos N, Vaughn DR, Turner PE, Ortiz DI, Wills W. 2001. Arbovirus surveillance in South Carolina 1996–98. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 17: 73–78.

Wood DM, Dang PT, Ellis RA. 1979. The insects and arachnids of Canada. Part 6. The mosquitoes of Canada, Diptera: Culicidae. Agriculture Canada, Hull, QC. 390 pp.