Raising a quality chicken starts with placing a quality chick in an optimal environment. The term “quality” is often used by poultry farmers when describing and evaluating their birds. However, most poultry farmers are confused about what characteristics to look for in their chicks. This publication aims to assist poultry owners in recognizing what is normal and abnormal and in evaluating quality when examining chicks. The intended audience is commercial and small flock poultry producers and poultry veterinarians.

What Does a Quality Chick Look Like?

Chicks should be alert and reactive to stimuli. They should have a dry and yellow fluffy covering. If chicks are from a single-age breeder flock, they should be uniform in size. The chicks should be well hydrated and free of mechanical defects. The navel should be properly healed (Figure 1).

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

Why Is Chick Quality Important?

If chicks have a good start, they are more likely to have a good finish. This is especially true today for broilers as they may be processed as young as 32 days of age. If the flock starts off with problems, it does not have time to recover and meet performance objectives for body weight, body weight uniformity, feed efficiency, and mortality. Starting off with high-quality chicks results in: 1) higher livability during the production cycle, 2) lower culling during the production cycle, 3) lower condemnations at processing, and 4) improved relations with poultry farmers when they receive a robust and viable chick to start with.

What Factors Affect Chick Quality?

Most poultry farmers believe that the hatchery is where chick quality is determined. However, there are other factors that have a major impact on the quality of the 1-day-old chick. The hatchery often has no control over these variables and must try to incubate what they receive. The breeder flock plays a major role in determining chick quality. The age, disease status, and history of the breeder farm all impact the quality of the chick. For example, age of the breeder flock has a major impact because young breeder flocks produce smaller fertile eggs, which result in smaller chicks. Smaller chicks are more fragile and weaker. These require extra care in the farm to get them to a good start. Older breeder flocks produce larger eggs with thinner shells. As the breeder flocks age, the level of bacterial contamination in the poultry house increases. The thinner-shelled eggs are much more prone to bacterial contamination. Thus, extra care in keeping nest boxes clean and disinfecting eggs is critical. Disease status of breeders can also impact eggshell quality and internal quality of fertile eggs. For example, if a breeder flock is infected with infectious bronchitis, eggshells will be thinner and egg whites will be more watery in consistency. Thinner eggshells result in an increased moisture loss during incubation and an increase in cracks which allow bacteria to enter the eggs. The history of a breeder flock is also important to consider. Management practices vary among farms. A lack of attention to detail by some farm managers results in increased contamination of nesting material and litter. This leads to an increased level of bacterial contamination of eggshells and then chicks.

Egg handling after lay can have a big impact on the quality of the chick. How eggs are handled on the farm, in transit to the hatchery, and in the hatchery will all impact percent hatch and chick quality. Soon after lay, fertile eggs need to be chilled and maintained below 68°F until prewarmed prior to placement in the incubator. Temperature management of eggs is crucial. Eggs must be stored below the temperature at which embryo development will occur, which is approximately 70°F. Additionally, after lay, if eggs are cooled at the breeder farm to 65°F, for example, each step along the way must be below 65°F. This includes transport in trucks to the hatchery and in the cooler in the hatchery. The temperature used to cool the eggs prior to incubation can vary based on storage duration. For 1–2 days of storage, 68°F is suitable, while for 10–12 days of storage, 60°F is used. Fluctuations of temperature and condensation on eggshells can adversely impact hatch and chick quality. This results in a decline in percent hatch and weaker chicks, which in turn bring about an increase in first week culling and mortality. Condensation on eggs results in an increase in bacterial contamination of the developing chicks because the water facilitates the entry of bacteria through the pores of the shell. Transport vehicles from the breeder farm to the hatchery should be properly serviced to ensure they can maintain the correct temperature. The vehicles should also have good suspensions to prevent jolts to the eggs en route.

After hatching, the chicks are processed and transported to the farm. Along the way, problems may occur which affect the chicks. After removing hatch trays from the hatcher, the chicks will be removed. They are examined and graded. Defective chicks will be culled. Common defects include improperly healed or infected navels, deformities, damaged hocks, dehydrated chicks, and undersized chicks. Often, several vaccines are administered by injection and spray in the hatchery. The chicks are held in chick boxes until transport to the farm. During this time, it is crucial to maintain correct temperature and ventilation to prevent heat stress or cold stress in the chicks. Newly hatched chicks are not able to control their body temperature. Thus, holding areas and transport vehicles must provide the ideal temperature and ventilation so chicks maintain a body temperature of 103°F–104.5°F. If body temperatures are too hot or too cold, it takes several days for the chicks to recover and perform to their genetic potential. Commercial broiler chickens have been selected for incredible growth and feed conversion. However, this genetic potential is only realized if birds are managed correctly, free of disease, and provided a balanced ration. The genetic potential for a strain of commercial chickens can be found in the management guide for the strain.

Once chicks arrive at the farm, it is the job of the farmer to provide an ideal environment where chicks are comfortable and can easily access feed and water. The newly hatched chicks have to figure out what feed and water are and where they are located. The birds need bright lighting the first week to help them find feed and water. The air temperature and ventilation must be ideal to ensure chicks move, eat, and drink. If they are cold, the chicks will simply pile up together to stay warm, and they will not make it to the feeders and drinkers. If overheated, they will become sleepy and inactive, and they are not going to eat and drink normally.

How to Evaluate a Chick

It is important to observe the exterior of the chick, to evaluate eyes, legs, navel, feathering, and activity level, and to look for signs of trauma. The eyes should be open, free of drainage and inflammation, and almost round (Figure 2). The legs should be yellowish in color. Some strains of chicks vary in color. The legs should be plump, suggesting the chicks are well hydrated. If the legs are darker and shrunken, and the medial vein is prominent, this would suggest the chicks are dehydrated (Figures 3 and 4). The hocks should be examined to see if they are red. This red color would indicate bruising, often associated with chicks struggling during the hatch process. Because these bruises are painful, these chicks will not walk to feeders and drinkers as needed to consume water and feed to develop normally (Figure 5). Also look at toes for any signs of mechanical trauma. Examine navels to evaluate if there is evidence of bacterial infection or if the navels healed properly after hatch (Figure 6). Common navel abnormalities are navel wicks, navel scabs, and navel bacterial infections. A navel wick is where a remnant of the umbilical blood vessel is present on the newly hatched chick. This is associated with excessively high relative humidity in the hatcher. The wick does not dry up and fall away. Navel scabs are found in newly hatched chicks and result from elevated temperatures in the hatcher. The elevated temperature results in the navel closing before all the yolk is pulled into the body cavity. Both of these abnormalities can increase the possibility of bacteria entry and infection (Figure 7). Evaluate feathering to see if it is dry and free of meconium. If it is still wet, the chick was removed too early from the hatcher. Presence of meconium suggests the chick was in the hatcher for too long after hatching. There are additional evaluations that can be conducted as part of a hatch residue analysis. This would involve collecting the eggs that did not hatch from the trays. These would be examined to determine if the egg was infertile or if the embryo died during the first, second, or third week of incubation. Weights of chicks can also be determined and compared to egg weights prior to incubation. The egg weights and chick weights can be compared to the standards for the genetic line used.

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

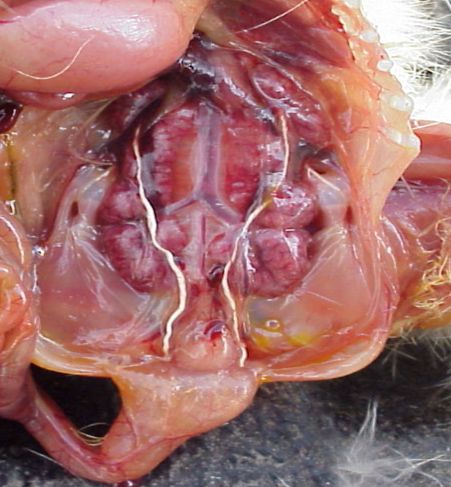

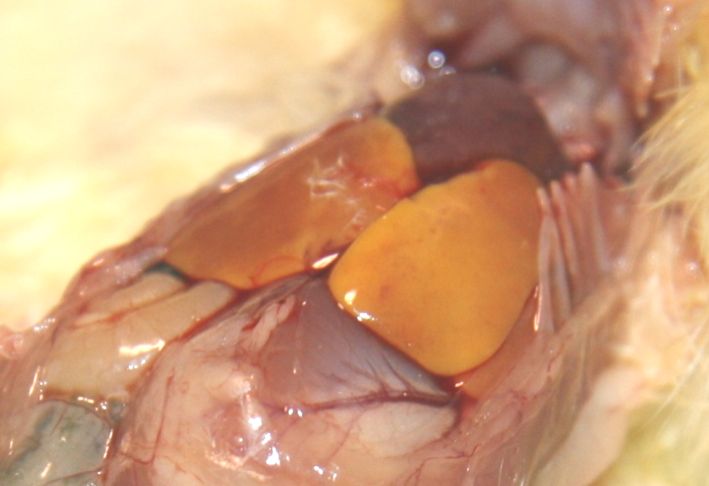

As part of a monitoring program, necropsies should be conducted to evaluate internal organs. The heart of the newly hatched chick should be red-brown in color. The pericardial sac surrounding the heart should be clear. The kidneys are red-brown-pink in color and the ureters should not be seen. If the chicks are dehydrated, white urates will be seen in ureters (Figure 8). The yolk sac will be within the body cavity after hatch. The color of the yolk sac varies from yellow to green (Figure 9). Many believe that a green yolk sac is evidence of a bacterial infection. This is not true. The yolk material should have the consistency of honey. The yolk will decrease in size as it is used and only a tiny remnant will be present at 7 days of age. If yolk is still present, this would suggest the yolk sac has a bacterial infection and the chick’s body is fighting off the infection. When infected with bacteria, the yolk is very watery or clumped and has a bad odor. Another reason a yolk sac may persist is if the chick is not eating and drinking. Chicks will not use the yolk sac for nutrients and hydration until there is feed in the intestinal tract. Many falsely believe chicks do not need feed and water for several days since they have a yolk sac. This is not true, as the yolk sac size will remain large if chicks are off feed. The liver color varies from mahogany to yellow to tan (Figure 10). These are all considered normal in the chick. The differences in color are determined by presence of fat in the liver. The lungs should be bright-pink in color.

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

Credit: Gary D. Butcher, UF/IFAS

Credit: Gary D. Butcher., UF/IFAS

Conclusion

The determination of chick quality is not simply a subjective determination. There are many parameters that can be used to evaluate the quality of chicks. Is behavior normal — are chicks acting and moving in a normal manner, or are they sleepy or piling up together? Are they alert and reactive? Are their eyes, legs, and feathering normal? On necropsy, are internal organs normal in appearance? When evaluating any animal, it is not possible to determine if there is a problem unless you have a good understanding of what “normal” is. Remember, a veterinary student does not start performing surgeries and necropsies on animals on day 1. The first half of their education is to learn what “normal” looks like. Only then can one identify when there is a problem. There are many misconceptions about the normal anatomy of the newly hatched chick. Many believe green-yellow yolks are evidence of bacterial infection, when these are normal. Many believe the yellow color of the liver is evidence of disease, when it is also normal. With experience and review of literature, poultry farmers can develop the skills to evaluate the quality of the chicks they receive.