Introduction

Cardinal flower is an herbaceous, native, erect, aquatic perennial plant that is commonly found in wet environments such as stream banks and swamps (Figure 1). The leaves of cardinal flower are 8 inches long and 2 inches wide. They are alternate, toothed, pointed at the ends, and either oblong or lance-shaped. This plant has showy, irregular, and tubular red flowers with 8-inch terminal spikes that are often over-picked in the wild. The flowers' upper portions have two lobes, and their lower portions are divided into three parts (Figure 2). The common name "cardinal flower" refers to the bright red robes worn by Roman Catholic cardinals. The fruit is a bell-shaped or oblong capsule that is about 4 inches long. Seeds are abundant, minute, brown, and elliptic to linear in shape. Cardinal flower can be used in landscaping as a wildflower in a moist garden, edging along a water garden, an understory plant in wet woods, a part of stream edge planting, and a member of a native plant or hummingbird garden.

Credit: Lyn Gettys, UF/IFAS

Credit: Lyn Gettys, UF/IFAS

Classification

Common Name: cardinal flower

Scientific Name: Lobelia cardinalis L.

Family: Campanulaceae (Bellflower family) (USDA NRCS 2015)

Description and Habitat

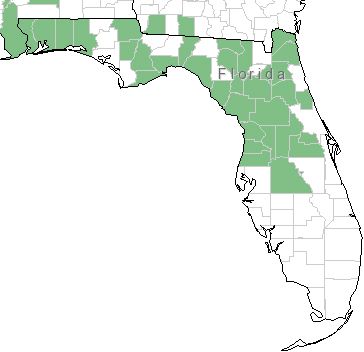

Cardinal flower is an obligate wetland species that grows well in sand or loam soil and exhibits low salt tolerance. This plant can be found in bogs and mats of floating vegetation, but its native habitat consists of wet ditches, ravines, depressions, woodland edges, stream banks, roadsides, meadows, swamps, and areas near lakes and ponds (USDA NRCS 2015). It is native to 42 counties in Florida from the panhandle to central Florida and is found primarily in north Florida. Populations of cardinal flower are also native between southeastern Canada and southeastern US, in Mexico, and from Central America to northern Colombia (USDA NRCS 2015). Plants are hardy in USDA Zones 3 through 9. Cardinal flower depends on hummingbirds for pollination.

Its genus, Lobelia, is considered to be potentially toxic because this plant contains a number of alkaloids. It is considered poisonous to humans and livestock and can cause death (Austin 2004). Overdoses will result in vomiting, paralysis, depressed body temperature, and coma.

Credit: USDA NRCS

Propagation

Cardinal flower can be propagated from seeds, cuttings, or division.

Instructions

Collect seed capsules in the autumn by cutting stalks below the capsules and placing them upside down in a sack. Leave the sack to air dry for a few days, then shake the bag to release the seeds. Sow seeds in a flat with a damp, fine grade peat mix. Keep them moist and under lights (the seeds need light to grow). Transplant seedlings after 4 to 6 weeks into individual pots with the same potting mix. Take cuttings that are between 4 and 6 inches in length with two nodes before the flowers open. Remove the lower leaf and half of the upper leaf. Dip cuttings in a rooting hormone and place in a 50 sand:50 perlite (v/v) media. Water lightly and keep moist. Roots generally form in 2 to 3 weeks. Cardinal flower may also be propagated by division of well-established clumps. Divide clumps in the fall or spring by separating the rosettes or basal offshoots from the mother plant and replanting the divisions. Water immediately.

Historical Uses

Cardinal flower once had ceremonial and medicinal uses for several Native American tribes. The Iroquois used cardinal flower to treat fever sores, cramps, and upset stomachs. It was often added to other medicines to increase their strength. The Delaware used cardinal flower as an infusion of roots to treat typhoid, while the Pawnee used the roots and flowers in love charms. The Meskwaki used the plant as a ceremonial tobacco, throwing it to the winds to ward off storms.

Summary

This plant depends on hummingbirds for pollination because insects have trouble navigating the flowers. As a result, it is an excellent native plant to add to any water garden in order to attract wildlife.

References

Austin, D. F. 2004. Florida Ethnobotany. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Florida Native Plant Society. 2015. "Lobelia cardinalis, cardinal flower, Campanulaceae." Accessed February 10, 2022. https://www.fnps.org/plant/lobelia-cardinalis

Native Plant Database. 2015. "Lobelia cardinalis, cardinal flower, Campanulaceae (bellflower family)." Accessed May 13, 2015. http://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=LOCA2

USDA NRCS. 2015. "Plant guide for cardinal flower, Lobelia cardinalis L." Accessed May 13, 2015. http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=LOCA2

Wunderlin, R. P., and B. F. Hansen. 2008. Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants. S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), Florida Center for Community Design and Research. Tampa, FL: Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida. http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu