Food diversity, nutritional food supply, and profitability are the priorities of agricultural and horticultural industries. To diversify vegetable products and increase the Florida vegetable industry's competitiveness, several new vegetable crops are rapidly emerging in the state. For example, there are more than 40 ethnic vegetable crops, such as luffa (Luffa cylindrica (L.) Roem), shalihon (Brassica juncea (L.) Czern), yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius (Poepp. and Endl.) H. Robinson), and tahn ho (Chrysanthemum coronarium L.), grown across Florida. Due to Florida's favorable climate, these vegetable crops grow well and have high market potential. The objective of this article is to provide a general overview on one of the Asian vegetable crops, long bean grown in Florida.

Long bean (Vigna unguiculata subs. sesquipedalis, Family: Fabaceae) is a leguminous vegetable crop with climbing vines that produce long pods consumed as a cooked vegetable. It is a popular crop in Asian countries such as in China. The subspecies name, "sesquipedalis," means "one-and-half-foot long" and approximates the pod length. It is also known as asparagus bean, Chinese long bean, long-podded cowpea, and yardlong bean. Long bean is called as bora, bodi, pea bean, and snake bean. This vigorous annual crop is a member of the genus Vigna, which is different from the common bean, which belongs to the genus Phaseolus.

This crop was recorded in Chinese literature as early as the Song Dynasty in 1008 CE, though China as the origin of long bean is not completely established. This crop is also considered to have originated from tropical Africa because wild species of Vigna can be found there (Yamaguchi 1983).

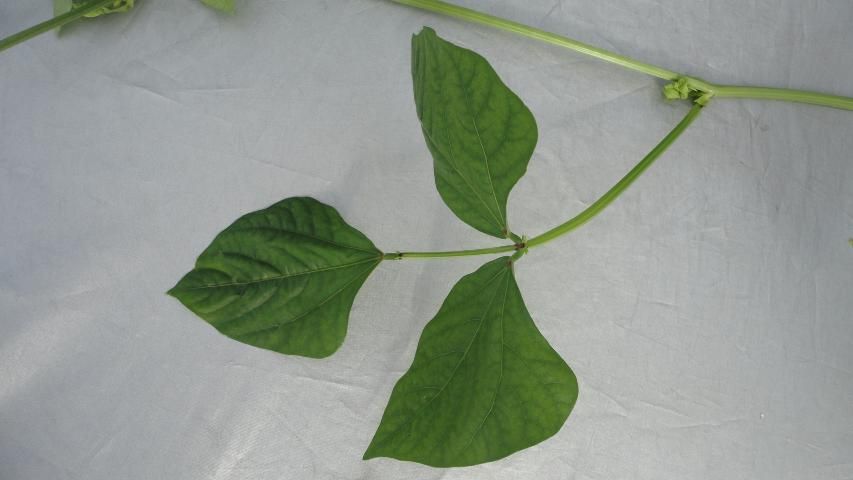

Long bean has two cotyledons (seed leaves), a significant part of the seed, and so is a dicotyledonous species. As an annual climbing vine crop, it has the following morphological (structural) features: purple or black kidney-shaped seeds (Figure 1) at maturity, two cotyledons (Figure 2), 3 to 4-inch-long trifoliate (divided into three leaflets) leaves with ovate (egg-shaped) leaflets (Figure 3); and violet or yellow flowers (Figure 4). This crop requires cross-pollination, usually by bees or other insects (Figure 5). The green, limp pods are usually 2 to 4 feet long and are straight or irregularly twisted (Figures 4–7) (Duke 1981). There are two types of long beans: light green (Figures 4 and 5) and dark green (Figure 7). As a leguminous crop, it can fix atmospheric nitrogen. Root inoculation with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Rhizobium can improve root nodule formation and reduce nitrogen fertilizer dependence.

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Kshitij Khatri, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Qingren Wang, UF/IFAS

Credit: Qingren Wang, UF/IFAS

Long Bean Can Be Grown Twice a Year in Florida

Florida has a favorable climate for producing long bean. It can be grown in north Florida in both spring and fall. The spring season starts in early March and ends in late July. The fall season begins in late July and finishes in mid-November. In south Florida, such as in Miami-Dade, long bean is grown from September or October through April and is harvested multiple times. The fall growing season in north Florida is more profitable because many competitors in some states in the north are unable to grow this crop in open fields and compete with Florida growers.

Long bean can be grown in a wide range of soil types from sandy loam to clay. The crop can tolerate a broad range of soil pH; however, recommended pH for best growth is 5.5–6.5. Long bean is a suitable crop for arid and semi-arid growth conditions because it can tolerate high heat, humidity, and drought stress. The crop grows well in warm climates with average monthly temperatures of 68°F to 86°F. Its preference for heat to germinate and grow makes it a suitable crop throughout the southeastern United States. However, plant growth is adversely affected by water logging, cold temperatures, and frost (Duke 1981). In south Florida, the extremely high humidity during the hot, rainy summer season often makes long bean susceptible to powdery mildew (Wang et al. 2014).

Planting

Long bean seeds can retain their viability for several years if they are kept in seed storage. This crop can be either transplanted or directly seeded. The seedlings can be transplanted when they have developed two true leaves. Transplanting allows earlier crop establishment and expands the growing season but also requires more labor. In Florida, direct seeding is the more common practice. The seeds are planted approximately 2 inches deep on raised beds with plants spaced 3 feet apart and beds spaced 6 feet apart. Plants can grow 9 to 12 feet tall, so a trellis support is needed. A trellis system 6 feet tall provides a good support for the climbing vines and facilitates harvesting (Lawrence 2012).

Fertilizer Application

This is a new crop rapidly expanding in north Florida. There is no UF/IFAS fertilizer recommendation yet, but UF/IFAS is working on this crop. Before the UF/IFAS recommendation becomes available, growers can apply fertilizers based on other leguminous crops such as snap bean, lima bean, and pole bean.

Harvesting

Long beans are ready to harvest 40 to 70 days after seeding, depending on location. This crop should be harvested at an immature stage when seeds are not fully matured. It is manually harvested daily when the pods are 10 to 12 inches long. Alternatively, it can be harvested as dried beans after seeds are fully developed and matured. Young leaves can be used to feed livestock, and the plant's large, attractive violet flowers with draping pods can serve as an ornamental plant in urban parks and gardens (Lawrence 2012).

Long Bean Is a Good Source of Human Nutrition

Long bean is a good source of protein, vitamins A and C, thiamin, riboflavin, and mineral nutrients including iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, and potassium (Table 1).

Further Information

Coker, C., M. Ely, and T. Freeman. "Evaluation of Yardlong Bean as a Potential New Crop for Growers in the Southeastern United States." HorTechnology 17 (4): 592–594.

Duke, J. A. 1981. Handbook of Legumes of World Economic Importance. New York: Plenum Press.

Lawrence, J. H. and L. M. Moore. 2012. Plant Guide: Yardlong Bean. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Accessed June 8, 2022. https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/pg_viuns2.pdf

Rubatzky, V.E. and M. Yamaguchi. 1997. World Vegetables: Principles, Production and Nutritive Values. Connecticut: A VI Publishing Company Inc. Springer; Softcover reprint of the original 2nd ed. 1997 edition (July 25, 2012).

US Department of Agriculture (USDA). "Yardlong bean, raw." Accessed June 8, 2022. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/169222/nutrients

Wang, Q., S. Zhang, and T. Olczyk. 2014. Management of Powdery Mildew in Beans. PP311. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Accessed June 8, 2022. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP311