External parasites of swine are a serious problem for Florida producers. Arthropod parasites limit production by feeding on blood, skin, and hair. The wounds and skin irritation produced by these parasites result in discomfort and irritation to the animal. In Florida, the major pests on swine are lice, mange mites, ticks and stable flies, although horse flies, deer flies, mosquitoes, and wound-infesting maggots may also cause severe problems.

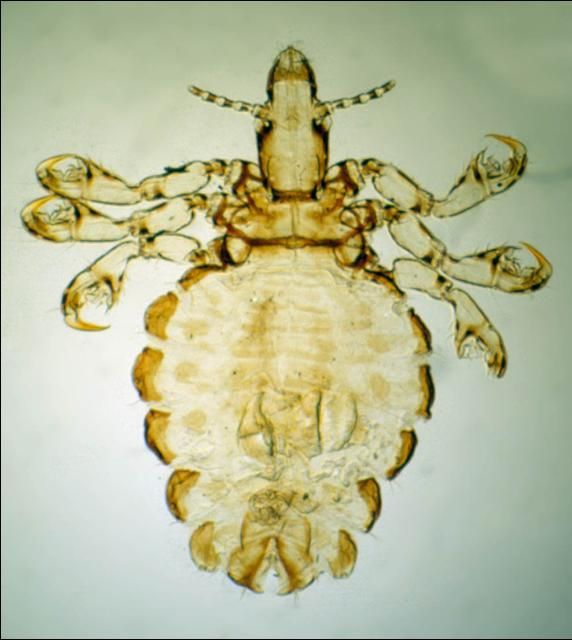

Hog Lice

The hog louse (Figures 1 and 2) is the most frequently found external parasite of swine in Florida. Louse populations increase in late October, and egg-laying adults can usually be found until June. High louse populations are usually found throughout the winter; however, lice also remain on the animal during the summer months.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Infested hogs are continually irritated by the nymphs and adults which pierce the skin to blood feed. Mature lice are about 1/4 inch in length and are gray-brown in color. Adults and nymphs attack principally the legs and folds of skin around the neck and ears. Each female louse lays an average of 90 eggs which are glued to the hairs (Figure 3). Within two weeks the eggs hatch into nymphs, which mature in 10 to 14 days.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Feeding lice irritate swine and infestations may be indicated by the animal's behavior. The irritation from louse feeding causes animals to rub or scratch vigorously on any convenient object, leading to weight loss. The skin becomes thickened and sometimes it cracks and produces sores.

The presence of louse infestations may be determined by examining the folds of skin around the neck and ears and also between the legs and body.

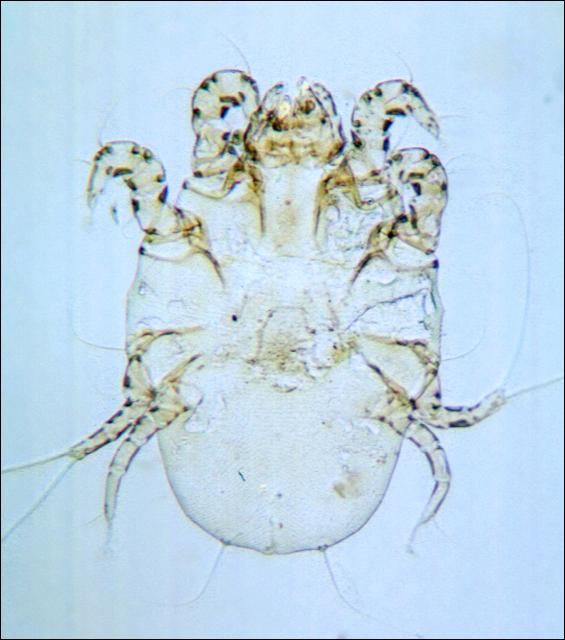

Mange

Mange in swine is caused by mange mites. Two principal types of mange mites are found in Florida.

Itch mites (sarcoptic mange (Figure 2) burrow just beneath the skin making slender, winding tunnels from 0.1 to 1 inch long. Fluid discharged at the tunnel opening dries to form nodules. A toxin is also secreted which causes intense irritation and itching. Infested animals rub and scratch constantly producing inflamed areas which may spread over the entire body. Infestations are contagious and treatment of all animals in a herd is essential to prevent transmission.

When mange is suspected, protect yourself from contamination. Mange can be transmitted to humans. After handling infested hogs, wash clothing in hot soapy water and shower thoroughly.

Follicular mites (demodectic mange) (Figure 3) are microscopic, cigar-shaped mites that also live in the skin. All life stages are found in the hair follicle. The mite produces nodular lesions that sometimes break, producing holes in the hide. Control is difficult since the mites are located deep in the hide.

Excessive scratching and rubbing may be an indication of mange. Follicular mange may produce inflamed areas and pustules on the belly, the head and top of the neck.

To make a positive identification of mange, scrape the edge or margin of suspected areas with a dull knife until bleeding starts or scrape contents of pustules. Examine scrapings under magnification.

Ticks

Several species of ticks may attack swine. These fall under two general groups, hard and soft ticks. Hard ticks are the most important group to attack swine. Hard ticks have a long association with the host, feed slowly, take a large blood meal, drop from the host to molt, and lay many eggs. Typical representatives are the American dog tick (Figure 4), brown dog tick, Gulf Coast tick (Figure 5), and rocky mountain wood tick.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Soft ticks (Figure 6) are of less importance to hogs. Soft ticks feed rapidly while a host animal is resting and then leave. A typical soft tick is the spinose ear tick.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

The effects of ticks on swine are inflammation, itching, and swelling at the bite site. Wounds may become infected.

Ticks are typically a problem on hogs that are allowed to access wooded areas.

Stable Flies

The stable fly (Figure 7) is similar to the house fly in size and color, but the bayonet-like mouthparts for sucking blood differentiate it. Stable fly bites cause irritation to animals and may account for much blood loss in severe cases. Wounds from bites may become infected. Stable flies are proven vectors of swine diseases such as hog cholera and leptospirosis.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Stable flies breed in soggy hay, grain or feed, piles of moist fermenting weeds, spilled green chop, peanut litter, and in manure mixed with hay or straw.

Stable fly control is most successfully approached by cultural control measures. The larvae require a moist breeding media. Therefore, the source of breeding should be dispersed to allow drying often enough to break the life cycle.

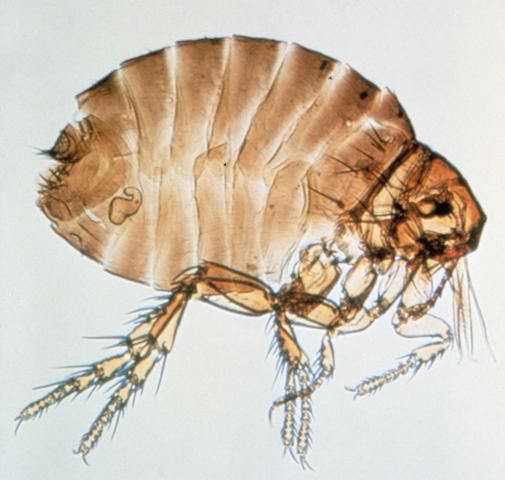

Sticktight Flea

The sticktight flea (Figure 8) is an important pest of swine in Florida. Although the flea is mainly considered to be a pest of poultry, the ears of hogs may often become lined with them.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Adult fleas line the ears of swine where they feed on blood and remain attached for several weeks. While feeding, the female lays eggs that fall to the ground. The eggs hatch and the larvae feed on organic matter in dry protected places. Within one month the larvae pupate and transform to adults.

Adult fleas feeding in the ears may cause ulceration and secondary infection.

Keys to Pesticide Safety

-

Before using any pesticide, stop and read the precautions.

-

Read the label on each pesticide container before each use. Heed all warnings and precautions.

-

Store all pesticides in their original containers away from food or feed.

-

Keep pesticides out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

-

Apply pesticides only as directed.

-

Dispose of empty containers promptly and safely.

Recommendations in this document are guidelines only. The user must insure that the pesticide is applied in strict compliance with label directions.

The Food and Drug Administration has established residue tolerances for certain insecticides in the meat of certain animals. When these and other approved insecticides are applied according to recommendations, the pests should be effectively controlled and the animals' products will be safe for consumption.

The improper use of insecticides may result in residue in milk or meat. Such products must not be delivered to processing plants. To avoid excessive residues, use the insecticides recommended at the time recommended and in the amounts recommended.

See ENY-272 Pesticide Safety around Animals for information on how to correctly and safely treat livestock with insecticides.

Locating an Approved Pesticide

In 2014, a group of livestock entomologists, as a part of Multistate Hatch Project S-1060, developed an online system for obtaining the names of registered pesticides appropriate for use with livestock and pets. This is a state-specific database (only certain states are represented, and Florida is one of these); if you are in another state, you must be certain that your state is represented in the dropdown list.

This database is easily searchable by the type of animal or site that you want to treat (such as a barn), as well as the targeted pest. From these two selections, you can then choose the "Method of Application" and the "Formulation Type." To use this system, please visit the following website https://www.veterinaryentomology.org/vetpestx.

Although the group continuously strive to keep this database current, it is ultimately your responsibility to ensure that the product that you choose is registered in the state that you plan to make the application and that you use the product in accordance with the label requirements and local laws and ordinances. Remember, "the label is the law" for pesticide use, and the uses indicated on the label, including the site of application and targeted pest(s) must be on the label.

If you have any challenges with this system, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office (http://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/map/index.shtml) or for additional assistance contact Dr. Phillip Kaufman, pkaufman@ufl.edu.

Selected References

Dee, S.A., J.A. Schurrer, R.D. Moon, E. Fano, C. Trincado, and C. Pijoan. 2004. "Transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus under field conditions during a putative increase in the fly population." J. Swine Health Prod. 12: 242–445.

Gore, J.C., L. Zurek, R.G. Santangelo, S.M. Stringham, D.W. Watson and C. Schal. 2004. "Water solutions boric acid and sugar for management of German cockroach populations in livestock production systems." J. Econ. Entomol. 97: 715–720.

Mercier, P., C. F. Cargill, and C. R. White. 2002. "Preventing transmission of sarcoptic mange from sows to their offspring by injection of ivermectin: Effects on swine production." Vet. Parasit. 110: 25–33.

Moon, R. D. 2002. Muscoid flies (Muscidae), In: Medical and Veterinary Entomology, (G. R. Mullen and L. A. Durden, eds.), pp. 45–65. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science.

Sheahan, B. J. 1974. "Experimental Sarcoptes scabiei infection in pigs: Clinical signs and significance of infection." Vet. Rec. 94: 202–209.

Sheahan, B. J., P. J. O'Connor and E. P. Kelly. 1974. "Improved weight gains in pigs following treatment for sarcoptic mange." Vet. Rec. 95: 169–170.

Steelman, C. D. 1976. "Effects of external and internal arthropod parasites on domestic livestock production." Ann. Rev. Entomol. 21: 155–178.

Williams, R. E. 1985. Arthropod pests of swine In: Livestock Entomology (R. E. Williams, R. D. Hall, A. B. Broce and P. J. Scholl, eds.), pp. 239–252. Wiley, New York.

Zurek, L. and C. Schal. 2004. "Evaluation of the German cockroach, Blatella germanica, as a vector of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli F18 in confined swine production." Vet. Microbiol. 101: 263–267.