Introduction

A new addition on the list of whitefly species found in Florida, Aleurodicus rugioperculatus Martin, was originally called the gumbo limbo spiraling whitefly, but is now named the rugose spiraling whitefly. Because it is a fairly new species to science—identified less than a decade ago—not much information is available about this pest. It is an introduced pest, endemic to Central America, and was reported for the first time in Florida from Miami-Dade County in 2009. Since then it has become an escalating problem for homeowners, landscapers, businesses, and governmental officials throughout the southern coastal counties of Florida. Feeding by this pest not only causes stress to its host plant, but the excessive production of wax and honeydew creates an enormous nuisance in infested areas. The presence of honeydew results in the growth of fungi called sooty mold, which then turns everything in the vicinity covered with honeydew black with mold.

Credit: Vivek Kumar, University of Florida

Distribution

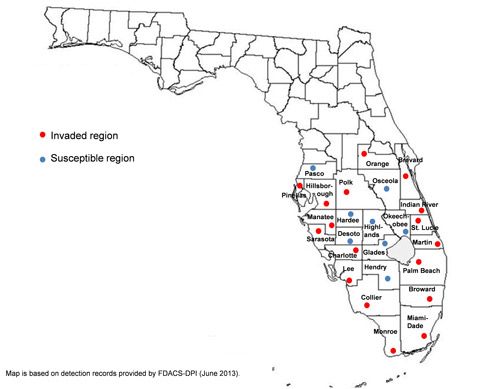

Distribution of this pest in Central and North America is limited to Belize, Mexico, Guatemala (Evans 2008), and the United States. In the continental United States, the first established population of rugose spiraling whitefly was reported from Florida in 2009, and since then its distribution range has expanded considerably within the state. According to an FDACS-DPI report (Stocks and Hodges 2012), until 2011, 75% of the samples received by DPI were from Miami-Dade county; however, in subsequent years there has been a rapid increase in its movement from the southern to the central parts of Florida. There have been reports of damage caused by this pest to ornamental plant hosts in at least 17 counties of Florida, with the maximum damage reported from Broward, Collier, Lee, Martin, Monroe, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach, and St. Lucie counties. One of the reasons behind these frequent reports from coastal areas could be the presence of a suitable climate and the availability of preferred hosts. Recent reports suggest it has moved from the coasts and invaded Orlando in Central Florida. Based on its dispersal potential, rugose spiraling whitefly may establish in eight other adjacent counties of Florida in the near future.

Credit: Map by Vivek Kumar, University of Florida

Description and Biology

Rugose spiraling whitefly was first described by Martin (2004) from samples collected in Belize on coconut palm leaves. The pest's biology is still under study because this species was discovered relatively recently. Scientists at the University of Florida have conducted biological studies that show the life cycle is approximately 30 days at 27°C (Mannion et al., unpublished data).

Adults

Rugose spiraling whitefly adults are about three times larger (approx. 2.5 mm) than the commonly found whiteflies and are lethargic by nature. Although taxonomic identification is required for species confirmation, rugose spiraling whitefly adults can be distinguished by their large size and the presence of a pair of irregular light brown bands across the wings (Stocks and Hodges 2012). Males have long pincer-like structures at the end of their abdomen.

Credit: Jennifer Wildonger, University of Florida

Credit: Holly Glenn, University of Florida

Eggs

Females lay eggs on the underside of leaves in a concentric circular or spiral pattern and cover it with white waxy matter. Eggs are elliptical and creamy white to dark yellow in color. Adult females sometimes lay their eggs on non-plant surfaces such as cars, windows, and walls.

Credit: Upper two photographs by Vivek Kumar, University of Florida. Lower photograph by Ian Stocks, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry

Immature Stages

Rugose spiraling whitefly has 5 developmental stages. The first instar, known as the crawler stage (because it is the only mobile immature stage) hatches out of the egg and looks for a place to begin feeding with its needle-like mouth parts used to suck plant sap. Crawlers molt into immature stages that are immobile, oval and flat initially but become more convex with the progression of its life cycle (Mannion 2010). Nymphs are about 1.1–1.5 mm long but may vary in size depending on instars. The nymphs are light to golden yellow in color, and will produce a dense, cottony wax as well as long, thin waxy filaments (Stocks and Hodges 2012), which get denser over time. The puparium of this species is used for taxonomic identification.

Credit: Ian Stocks, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry

Hosts

Rugose spiraling whitefly feeds on a wide range of host plants including palms, woody ornamentals, and fruits (Mannion 2010). DPI host record from 2009 to 2012 showed that 22% of rugose spiraling whitefly-affected hosts were palm species, 16% were gumbo limbo, 10% were Calophyllum spp., 9% were avocado, 4% were black olive, and 3% were mango varieties (Francis et al. 2016). Within the family Arecaceae (palms), 44% of host records were from coconut. Based on incidence records, these plant species can be considered as primary or preferred hosts of this pest. As of June 2015 (Francis et al. 2016), rugose spiraling whitefly has been identified on at least 118 plant species, which include a combination of edibles, ornamentals, palms, weeds, as well as native and invasive plant species (Stocks 2012). However, all plant species reported have not been documented as true hosts of the pest and may not require management. An insect must be able to complete its entire life cycle (egg to adult) to be considered a true host plant. Some plant species may not support the complete development of rugose spiraling whitefly but may still be used by adult whiteflies for feeding and laying eggs. Thus, the level of feeding by adult whiteflies and development of other stages will determine the impact the whitefly has on the host plant and if management is required. List of rugose spiraling whitefly host plants.

Credit: Vivek Kumar, University of Florida

Credit: Vivek Kumar, University of Florida

Damage

Infestation of this pest usually does not kill the host plant, but it may interfere with the normal growth of its host. Rugose spiraling whitefly can cause stress to the plant by removing nutrients and water and by promoting the growth of black sooty molds. Rugose spiraling whitefly excretes a sticky, glistening liquid substance (honeydew), which provides an excellent substrate for growth of sooty molds, which turn the shiny liquid into a black-colored viscous liquid. Once it dries, the sooty mold forms thick layers on the host leaves and other non-plant surfaces. The layers of sooty mold on leaves may disrupt the photosynthesis process in the host leading to physiological disorders. Honeydew also attracts ants and wasps that protect the whiteflies from their natural enemies (Stocks and Hodges 2012).

In addition to damaging its host, rugose spiraling whitefly also creates a nuisance in the area of infestation. Honeydew, sticky wax, sooty mold, and bodies of dead whiteflies fall onto understory plants and non-plant surfaces such as automobiles, patios, and furniture. When these materials fall into swimming pools the contamination can impact water chemistry and clog filters. Dried sooty mold does not wash off easily and may require pressure washing and/or professional cleaning. The price for managing this pest may also be substantial depending upon the method of treatment and insecticide used, as well as the size and type of host plant treated. Depending upon the number and type of trees that need to be treated, price may vary for foliar or drench treatment between $28 to $40 per tree/year (pers. comm. Royal Green, 2013) and for tree injection it may be about $50 per tree/year (pers. comm. Brian Reynolds, Reynolds Pest Management, 2013).

Symptoms of Damage

- egg spirals of rugose spiraling whitefly on the underside of leaves

- presence of heavy, white, waxy material

- presence of sticky honeydew around the whitefly infested area

- black sooty mold formation

- leaf damage and early leaf drop (not evident on all types of plants) (from Mayer et al. 2010)

Credit: Vivek Kumar, University of Florida

Credit: Vivek Kumar, University of Florida

Management

Effective monitoring is extremely important in order to keep populations under a damaging level. At the initial stage of infestation, pressure washing with water can be effective in reducing pest populations; however, it must be repeated at regular intervals, removing many of the eggs and immature stages from the hosts (and care must be taken not to damage plants). Soaps and horticultural oils can also be used for this purpose but require thorough coverage and repeated application.

Chemical Control

Only use insecticides when necessary and follow all label instructions. At present, chemical treatment is considered the primary mode for managing this pest. Numerous insecticides are available to control whitefly, but the method of application and site to use the product will vary by label (Mannion 2010). Effective control can be achieved using systemic application (soil or trunk) insecticides. Systemic insecticides can be applied by licensed professionals to the soil (drenching, granular formulations, burying pellets, or soil injection), to the trunk (basal bark spray and trunk injection), or to the foliage; however, soil and trunk applications take advantage of the systemic properties of these products and provide longer term control (Mannion 2010). Most contact insecticides can be applied to the foliage and can provide quick knockdown of the whiteflies, but will typically provide only a few weeks of control.

Pesticides can kill the biological control agents discussed below and should be used only as a last resort. The University of Florida and FDACS (Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services) have developed a website that is used to teach people about invasive whitefly pests in Florida. Florida Whitefly is a website portal focused on Florida whitefly issues of concern to landscape professionals, homeowners, and the public.

Credit: Vivek Kumar and Lance S. Osborne

Biological Control

Two parasitoids, Encarsia guadeluopae Viggani and Encarsia noyesii Hayat (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae), and the beetle predator, Nephaspis oculatus (Blatchley), have shown the most promise for use against rugose spiraling whitefly, but are not commercially available at this time. All of these natural enemies are often found on the plants infested with rugose spiraling whitefly and are continuing to spread northward. The search is under way for additional biological control agents and developing methods to rear and release known natural enemies (Osborne 2012).

Credit: Vivek Kumar, University of Florida

Selected References

Evans GA. 2008. The whiteflies (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) of the world and their host plants and natural enemies. USDA-APHIS. (January 2017)

Francis A, Stocks IC, Smith TR, Boughton AJ, Mannion C, Osborne L. 2016. Host plants and natural enemies of rugose spiraling whitefly (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Florida. Florida Entomologist 99: 150–153. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.099.0134

Mannion C. 2010. Rugose spiraling whitefly, a new whitefly in South Florida. UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center. p. 5. (December 2024)

Martin JH. 2004. The whiteflies of Belize (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) Part 1—introduction and account of the subfamily Aleurodicinae Quaintance & Baker. Zootaxa 681: 1–119. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.681.1.1

Mayer H, McLaughlin J, Hunsberger A, Vasquez L, Olcyzk T, Mannion C. 2010. Common questions about the gumbo limbo spiraling whitefly (Aleurodicus rugioperculatus). UF/IFAS Extension Miami Dade County. p. 4. (January 2017)

Osborne LS. 2012. The rugose spiraling whitefly. Mid-Florida Research and Education Center, University of Florida. (January 2017)

Stocks I. 2012. Rugose spiraling whitefly host plants. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry. p. 6. (January 2017)

Stocks I, Hodges G. 2012. Pest Alert- DACS-P-01745. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry. p. 6. (January 2017)