The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The American cockroach, Periplaneta americana (Linnaeus), is the largest of the common peridomestic cockroaches measuring on average 4 cm (1.5 in) in length. It occurs in buildings throughout Florida, especially in commercial buildings. In the northern United States, the cockroach is mainly found in steam heat tunnels or large institutional buildings. The American cockroach is second only to the German cockroach in abundance.

Credit: Paul M. Choate, University of Florida

Distribution

Forty-seven species are included in the genus Periplaneta, none of which are endemic to the US (Bell and Adiyodi 1981). The American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) was introduced to the United States from Africa as early as 1625 (Bell and Adiyodi 1981). The American cockroach has spread throughout the world by commerce. It is found mainly in basements, sewers, steam tunnels, and drainage systems (Rust et al. 1991). This cockroach is readily found in commercial and large buildings such as restaurants, grocery stores, bakeries, and anywhere food is prepared and stored. The American cockroach is rarely found in houses; however infestations can occur after heavy rain. They can develop to enormous numbers, greater than 5,000 sometimes being found in individual sewer manholes (Rust et al. 1991).

Outdoors, American cockroaches are found in moist, shady areas such as hollow trees, wood piles, and mulch. They are occasionally found under roof shingles and in attics. The cockroaches dwell outside but will wander indoors to search for food and water or to avoid extreme weather conditions. In Florida, areas such as trees, woodpiles, garbage facilities, and accumulations of organic debris around homes provide adequate food, water, and harborages for peridomestic cockroaches such as the American cockroach (Hagenbuch et al. 1988).

Mass migrations of the American cockroaches are common (Ebeling 1975). They migrate into houses and apartments from sewers via the plumbing, and from trees and shrubs located alongside buildings or with branches overhanging roofs. During the day the American cockroach, which responds negatively to light, rests in harborages close to water pipes, sinks, baths, and toilets where the microclimate is suitable for survival (Bell and Adiyodi 1981).

Description

Eggs

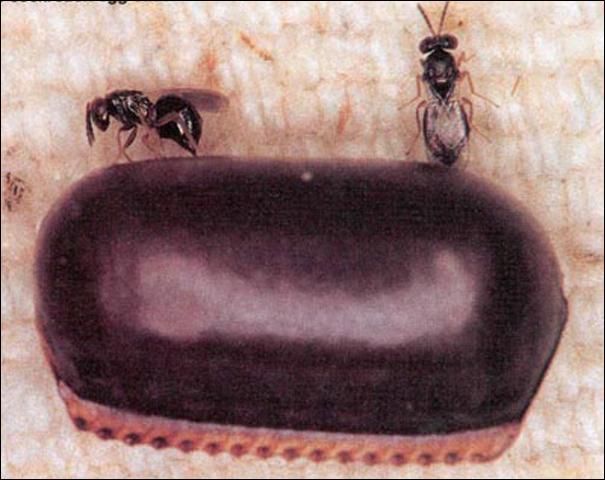

Females of the American cockroach lay their eggs in a hardened, purse-shaped egg case called an ootheca. About one week after mating the female produces an ootheca and at the peak of her reproductive period, she may form two oothecae per week (Bell and Adiyodi 1981). The females on average produce one egg case a month for ten months, laying 16 eggs per egg case. The female deposits the ootheca near a source of food, sometimes gluing it to a surface with a secretion from her mouth. The deposited ootheca contains water sufficient for the eggs to develop without receiving additional water from the substrate (Bell and Adiyodi 1981). The egg case is brown when deposited and turns black in a day or two. It is about 8 mm (1/3 in) long and 5 mm (3/16 in) high.

Nymph

The nymphal stage begins when the egg hatches and ends with the emergence of the adult. The number of times an American cockroach molts varies from six to 14 (Bell and Adiyodi 1981). The first instar American cockroach is white immediately after hatching then becomes a grayish brown. After molting, subsequent instars of the cockroach nymphs are white and then turn reddish-brown with the posterior margins of the thoracic and abdominal segments being a darker color. Wings are not present in the nymphal stages and wing pads become noticeable in the third or fourth instar. Complete development from egg to adult is about 600 days. The nymphs as well as the adults actively forage for food and water.

Credit: Paul M. Choate, University of Florida

Adult

The adult American cockroach is reddish brown with a pale brown or yellow band around the edge of the pronotum. The males are longer than the females because their wings extend 4 to 8 mm (~1/8 to 1/3 in) beyond the tip of the abdomen. Males and females have a pair of slender, jointed cerci at the tip of the abdomen. The male cockroaches have cerci with 18 to 19 segments while the females' cerci have 13 to 14 segments. The male American cockroaches have a pair of styli between the cerci while the females do not.

Credit: P.G. Koehler, University of Florida

Credit: P.G. Koehler, University of Florida

Credit: P.G. Koehler, University of Florida

Life Cycle

The American cockroach has three life stages: the egg, a variable number of nymphal instars, and the adult. The life cycle from egg to adult averages about 600 days, and the adult life span may be another 400 days. The nymphs emerge from the egg case after about six to eight weeks and mature in about six to twelve months. Adults can live up to one year and an adult female will produce an average of 150 young in her lifetime. Environmental factors such as temperature and humidity affect the developmental time of the American cockroach. Outdoors, the female shows a preference for moist, concealed oviposition sites (Bell and Adiyodi 1981).

Credit: J.L. Castner, University of Florida

Diet

The American cockroach is an omnivorous and opportunistic feeder. It consumes decaying organic matter but is a scavenger and will eat almost anything. It prefers sweets, but has also been observed eating paper, boots, hair, bread, fruit, book bindings, fish, peanuts, old rice, putrid sake, the soft part on the inside of animal hides, cloth, and dead insects (Bell and Adiyodi 1981).

Medical and Economic Significance

American cockroaches can become a public health problem due to their association with human waste and disease and their ability to move from sewers into homes and commercial establishments. In the United States during the summer, alleyways and yards may be overrun by these cockroaches. The cockroach is found in caves, mines, privies, latrines, cesspools, sewers, sewage treatment plants, and dumps (Bell and Adiyodi 1981). Their presence in these habitats is of epidemiological significance. At least 22 species of pathogenic human bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoans, as well as five species of helminthic worms, have been isolated from field collected American cockroaches (Rust et al. 1991). Cockroaches are also aesthetically displeasing because they can soil items with their excrement and regurgitation.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Management

Several hymenopteran natural enemies of the American cockroach have been found (Suiter et al. 1998). These parasitic wasps deposit their eggs in the cockroach ootheca preventing the emergence of cockroach nymphs.

Credit: Pest Control magazine (used with permission)

Caulking of penetrations through ground level walls, removal of rotting leaves, and limiting the moist areas in and around a structure can help in reducing areas that are attractive to these cockroaches.

Other means of management are insecticides that can be applied to basement walls, wood scraps, and other infested locations. Residual sprays can be applied inside and around the perimeter of an infested structure. When insecticides and sprays are used to manage cockroach populations, they may ultimately kill off the parasitic wasps. Loose, toxic pellet baits are extremely effective in controlling America cockroach populations.

Cockroaches and Their Management, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ig082

Selected References

Appel A.G. 1997. Nonchemical approaches to cockroach control. Journal of Economic Entomology 14: 271–280.

Baldwin, R.W. and P.G. Koehler. 2007. Toxicity of commercially available household cleaners on cockroaches, Blattella germanica and Periplaneta americana. Florida Entomologist 90: 703–709.

Bell, W.J. and K.G. Adiyodi. 1981. The American cockroach. Chapman and Hall, London.

Ebeling, W. 1975. Urban Entomology. University of California, Richmond, CA.

Hagenbuch, B.E., P.G. Koehler, R.S. Patterson, and R.J. Brenner. 1988. Peridomestic cockroaches (Orthoptera: Blattidae) of Florida: Their species composition and suppression. Journal of Medical Entomology 25(5): 377–380.

Rust, M.K., D.A. Reierson, and K.H. Hansgen. 1991. Control of American cockroaches (Dictyoptera: Blattidae) in sewers. Journal of Medical Entomology 28(2): 210–213.

Shaheen, L. 2000. Environmental protection comes naturally. Pest Control. 68: 53–56.

Suiter, D.R. 1997. Biological suppression of synanthropic cockroaches. Journal of Agricultural Entomology 14: 259–270.

Suiter, D.R., R.S. Patterson, and P.G. Koehler. Seasonal incidence and biological control potential of Aprostocetus hagenowii (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) in treehole microhabitats. Journal of Environmental Entomology 27: 434-442.

Valles, S. (September 1996). German cockroach, Blatella germanica (Linnaeus). UF/IFAS Featured Creatures. EENY-002. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN128 (26 April 2017).