The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Tomicus piniperda (Linnaeus), a pine shoot beetle native to Europe, was first discovered in the United States in July 1992 in a Christmas tree plantation in Ohio. Because Tomicus piniperda occurs about as far south in the Old World as the latitude of Florida, it is considered a potential threat to at least some of the pine species intensively cultivated in Florida, as well as pine species in other states.

Credit: Steve Passoa, USDA APHIS PPQ, www.forestryimages.org

Distribution

The beetle is found in numerous countries worldwide, including:

Africa: Algeria, Canary Islands, China (northeast)

Asia: Japan, Korea, Turkey

Europe: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Madeira, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland

North America: Canada, United States

(USDA 1972, GISD 2007, USDA 2010).

In the United States, as of 2010, it is found in 17 northeastern and north central states. In Canada, it is established in the Great Lakes regions of Ontario and Quebec (Humphreys and Allen 1998, USDA 2010).

Identification

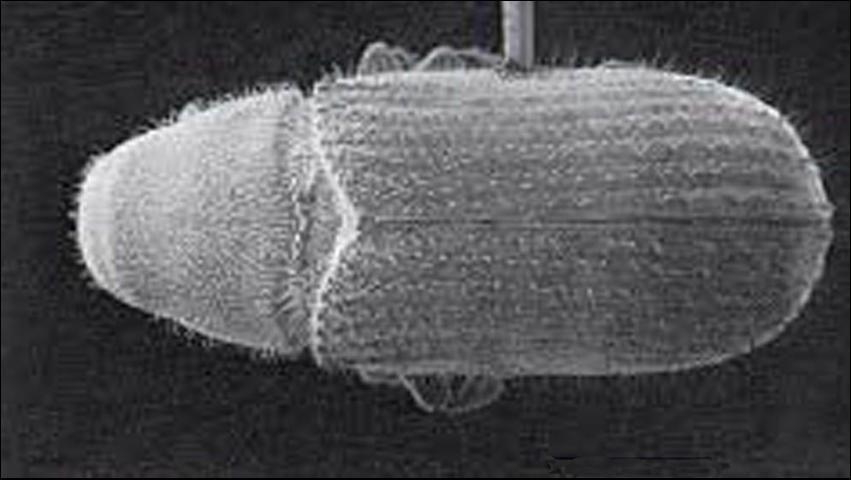

Tomicus piniperda adults are brown to black, 3.5 to 4.8 mm long, and somewhat resemble individuals of Dendroctonus (southern pine beetle and black turpentine beetle) in general appearance, but the funicle of the antenna is composed of six antennomeres. Tomicus piniperda can be distinguished from other members of the genus by the smooth second elytral interval on the declivity.

Credit: Gyorgy Csoka, Hungary Forest Research Institute, www.forestryimages.org

Credit: USDA

Biology

The following information is derived from Hanson (1940), who studied the life cycle of Tomicus piniperda in Great Britain. This species overwinters as an adult, either in hollowed twigs or in galleries at the base of the tree, emerging as early as February in warm localities to construct brood galleries at the base of the tree trunk. Development from egg to adult requires about three months, with adults of the new generation beginning to emerge in June.

Credit: William M. Ciesla, Forest Health Management International, www.forestryimages.org

The new adults are sexually immature and move into the tree crown to feed on the growing tips throughout the summer. The adults which overwintered also move into the crowns for what is known as "regeneration feeding." These individuals then move back into the trunks to construct new galleries and to lay a second batch of eggs. The adults of this second brood usually emerge late in the summer. In Great Britain there is usually only one generation per year; in warmer countries there may be two generations annually.

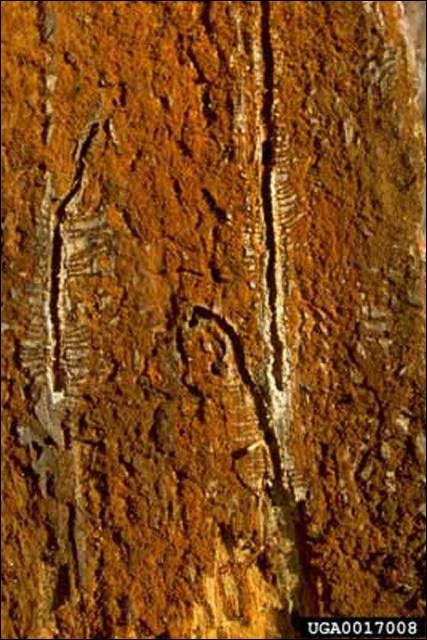

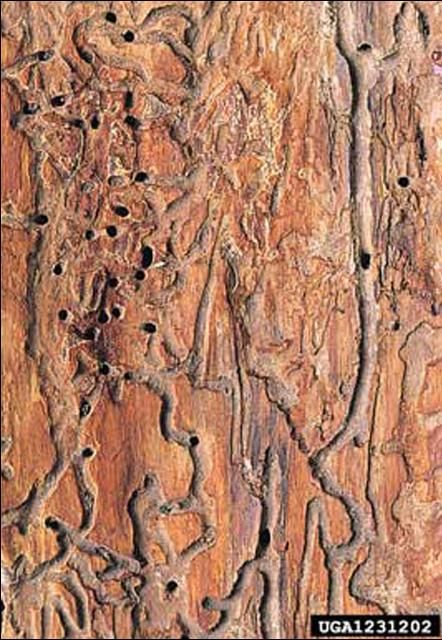

Studies by the Canadian Forest Service confirm that the pine shoot beetle completes one generation per year in that region and the northern United States. Overwintering adults begin flights during March in the Great Lakes area, when daily maximum temperatures reach 10 to 12°C and the daily mean temperature is 7 to 8°C. The adults can fly for several kilometers to find a suitable host. The adult beetles prefer to colonize freshly cut stumps and slash but can attack stressed living trees. The females excavate galleries, 10 to 25 cm long, under the bark to lay their eggs with the galleries more numerous on the sides of logs and trees warmed by the sun (Humphreys and Allen 1998).

Credit: Gyorgy Csoka, Hungary Forest Research Institute, www.forestryimages.org

After laying eggs in the galleries, the adults emerge and then die. The larvae soon emerge and feed in separate galleries 2.5 to 10 cm long from April through June. In May or June, larvae pupate at the end of their feeding galleries. The new generation emerges through the bark and attacks new shoots on pine trees of all ages. The beetles damage the new growth by burrowing up to 10 cm into the pith. In October, the adults move into the soil or the base of pine trees to overwinter. While adults can overwinter in shoots in warmer climates, they must move under the bark at the base of trees or the soil in colder weather. Snow pack adds insulation in many areas of Canada and the more northern United States (Humphreys and Allen 1998).

Economic Importance

This species is considered the most serious scolytid pest of pines in Europe. It attacks both the trunks and growing shoots of pines, especially Scotch pine, Pinus sylvestris L. In Europe, it occasionally attacks spruce (Abies sp.) and larch (Larix sp.). It especially attacks weakened, stressed, or dying trees, but will also attack and kill apparently healthy trees. In the United States, it has been found most commonly in Pinus sylvestris, but also in Austrian pine, Pinus nigra, and eastern white pine, Pinus strobus.

According to Hanson (1940), the worst damage caused by the beetle is the tip feeding: "This destruction of the growing points causes various forms of malformation ... and results in great reduction of the value of the crop." Trees may be destroyed by the tip feeding, or by the feeding in the trunk, or by attack of other insects caused by the stress. This kind of damage would be especially severe in Christmas tree plantations, where tree form is the primary consideration, as "...the injuries caused by [Tomicus] are of a permanent character and the record of the insect's attack is indelibly stamped on the tree..." (Hanson 1937). It has recently been reported by Hui (1991) as a severe pest of Pinus yunnanensis L. in the Kunming Region of China, where it killed many apparently healthy trees and "... caused great economic losses."

Credit: Robert A. Haack, USDA Forest Service, www.forestryimages.org

Credit: Bruce Smith, USDA APHIS PPQ, www.forestryimages.org

It is believed that four species of pines native to Florida might be susceptible to attack by Tomicus piniperda, based primarily on resin flow and bark characteristics:

- sand pine, Pinus clausa (Chapm. ex Engelm.) Vasey ex Sarg.

- spruce pine, Pinus glabra Walt.

- pond pine, Pinus serotina Michx. and

- loblolly pine, Pinus taeda L.

Forest resources that may be threatened include Christmas trees, pine landscape/nursery products, and pine timber. Loblolly pine is the most important commercial species with a growing volume in Florida of almost 675 million cubic feet. Sand pine is the primary Christmas tree crop and annual retail sales of Florida Christmas trees amount to about US $3 million. Figures were gathered from federal, state, and industry sources.

Survey

Symptoms of attack include dieback, yellowing, and especially dead, bored-out shoots littering the ground under infested trees (USDA 1972). Damage may resemble that sometimes caused by Ips spp. or by pine tip moths (Rhyacionia spp.) and any shoot damage should be carefully examined. Look for 2 to 3 mm circular exit and entrance holes created by the adults near the broken ends of the shoots. In addition, first and second year shoots droop and become yellow or red in early summer (Humphreys and Allen 1998).

Credit: Gyorgy Csoka, Hungary Forest Research Institute, www.forestryimages.org

Credit: Gyorgy Csoka, Hungary Forest Research Institute, www.forestryimages.org

Credit: Bruce Smith, USDA APHIS PPQ, www.forestryimages.org

Credit: Steve Passoa, USDA APHIS PPQ, www.forestryimages.org

Management

There apparently is no practical chemical control for this pest. Cultural practices used in Europe include precise timing of cutting operations and the debarking of cut timber.

A predatory beetle, Thanasimus formicarius Linnaeus, can eat several pine shoot beetles daily. Thanasimus formicarius disperse just before the flight of their prey (Tomicus piniperda and Tomicus minor as well as other bark beetles) or during, or just after. Often, they are waiting on the fallen pine trees and begin feeding on bark beetles as they land. Both Thanasimus formicarius and the bark beetles are attracted to monoterpenes from the damaged areas of the fallen trees.

Credit: Scott Bauer, USDA

A quarantine on the movement of host trees from infested states exists, both from states that are not infested and between infested and non-infested areas of states where the pine shoot beetle is established. Check to see if a state has a pine shoot beetle compliance program before moving or accepting trees from infested areas (MG 2001).

Selected References

Byers J. (2004). Thanasimus formicarius. Chemical Ecology of Insects. http://www.chemical-ecology.net/insects/tformi.htm (September 2019)

GISD. (October 2007). Tomicus piniperda (insect). Global Invasive Species Database. http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/speciesname/Tomicus+piniperda (September 2019)

Hanson S. 1937. Notes on the ecology and control of pine beetles in Great Britain. Bulletin of Entomological Research 28: 185–236.

Hanson S. 1940. The prevention of outbreaks of the pine beetles under war-time conditions. Bulletin of Entomological Research 31: 247–251.

Hui Y. 1991. On the bionomy of Tomicus piniperda (L.) (Col., Scolytidae) in the Kunming region of China. Journal of Applied Entomology 112: 366–369.

Humphreys N, Allen E. (1998). Exoric Forest Pest Advisory. The pine shoot beetle. Canadian Forest Service, Pacific Forestry Centre, Victoria, British Columbia. 4 pp.

[MG]. (2001). Summary - State of Maine pine shoot beetle regulations. Maine.gov (no longer available online)

NAPIS. (2010). Pine shoot beetle, Tomicus piniperda. National Agricultural Pest Information System. (no longer available online)

NAPPO. (2006). Update on quarantine areas for pine shoot beetle (PSB), (Tomicus piniperda), in Iowa, Michigan, and Ohio. Phytosanitary Alert System. http://www.pestalert.org/oprDetail.cfm?oprID=207 (September 2019)

USDA. 1972. Insects not known to occur in the United States. A bark beetle (Tomicus piniperda (Linnaeus)). USDA Cooperative Economic Institute Report 22: 234–236.

USDA. (November 2010). Pine shoot beetle. USDA APHIS Plant Detection and Management Programs. http://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant_health/plant_pest_info/psb/index.shtml (September 2019)