Pests of all shapes and sizes have vexed humanity since our earliest days. From disease-carrying mosquitos, to weeds and insects that reduce crop yields, to disease in well-manicured rose gardens, pests often require some level of management. UF/IFAS recommends an integrated pest management (IPM) plan that seeks to utilize all available management tools to effectively mitigate pest problems.

Credit: Brett Bultemeier, UF/IFAS

One of the tools in the IPM toolbox is pesticides. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2018) defines a pesticide as:

- Any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, repelling, or mitigating any pest

- Any substance or mixture of substances intended for use as a plant regulator, defoliant, or desiccant

- Any nitrogen stabilizer

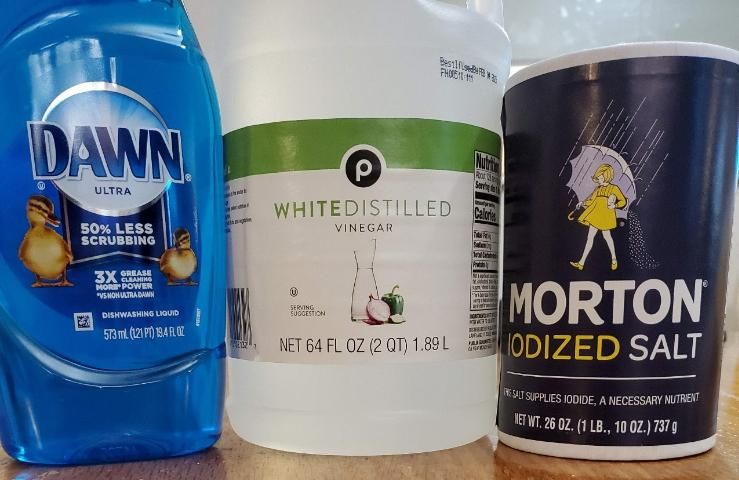

Though pesticides are thoroughly tested and pose little risk to the applicator or environment when used according to the label, many individuals are not comfortable with chemical pest management options. There are gardening newsletters or social media posts that discuss "do-it-yourself" pesticide mixes that can be made using common household ingredients. This can be viewed as a great alternative to conventional pesticides, but before using the homemade mixes, we need to address some fundamental questions: 1) Are these homemade pesticides legal to use? and 2) If so, can I request my lawn contractor to use these mixtures?

Credit: Brett Bultemeier, UF/IFAS

Are homemade mixtures "pesticides"?

According to the definition above, if a substance is meant to kill, repel, or reduce the impact of a "pest," be it a weed, bug, or animal, it is a pesticide. Furthermore, many home remedies will label themselves as "organic" or "natural." Although these mixes might be "organic," like vinegar and salt mixes, they are still classified as pesticides if they are used to manage a pest. In short, if you are making and using a substance with the intent of reducing a pest population, you are using a pesticide.

Are homemade pesticides legal?

The EPA further classifies that something is likely to be a pesticide and regulated under the purview of the EPA if: 1) it makes claims of pest control; 2) it is distributed and sold as such; or 3) it is utilized as a service that claims to control a pest (this counts as distribution) (FIFRA Federal Regulations e-CFR Title 40, Chapter 1, Subchapter E, Part 152, Subpart A). Therefore, if someone were to mix a batch of a "homemade pesticide for weed control" in their garage and provide it to their neighbors claiming that it will control a pest, then they have just distributed a pesticide. If it isn't registered, then both state and federal laws have been broken, and legal consequences could be imposed.

What if that same person decides not to give away or sell their home remedy, but sprays it on neighbors' lawns and charges for the application? They have now been contracted for pesticide work, which requires the use of a registered pesticide. If that home remedy isn't registered by the EPA and the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, then once again this is illegal.

There are several substances that the EPA has deemed "Minimum Risk Pesticide Products" that can be used without requiring federal registration (Title 40, Chapter 1, Subchapter E, Part 152.25). A homemade pesticide containing only the ingredients listed in that section would not require registration with the EPA. However, that product cannot be used on food, unless food tolerances have been established found in part 180 of Subchapter E and cannot be used against disease-carrying insects or microorganisms that pose a threat to human health. Additionally, the product must bear a label listing the ingredients as a percentage by weight and have information about who made it and how to contact the manufacturer. Further information can be found from the EPA Minimum Risk Pesticides page (https://www.epa.gov/minimum-risk-pesticides).

If homemade pesticides can be illegal, then why are recipes advertised freely online? It is not illegal to make and use homemade pesticides, but it is illegal to sell, distribute (even for free), or apply them as a contractor. Therefore, if someone makes a home remedy in their garage and uses it only on their own property, that might be legal. But there are still two more considerations: 1) Do any of the substances have language preventing them from being put out in the environment? and 2) When they use this homemade pesticide, are they applying it to something they are "producing" and selling, such as vegetables or ornamental plants? If either of these two scenarios exists, then they have again run afoul of legal requirements. If the homemade pesticide has no prohibitions, it is only used on their own property, and they are not producing anything or selling it, then the homemade pesticide would be legal.

It's legal, but is it safe?

The EPA states that all of its registered products, if used according to all label directions, will not cause undue harm to people, nontarget species, or the environment (EPA 2017). The process for registering a pesticide includes hundreds of tests to determine how long it persists in the environment, the potential to contaminate groundwater, and its toxicity profile, to name a few. All this testing guides where a product can be used, when it can be used, how much can be used, and what safety procedures (i.e., personal protective equipment, or PPE) would be needed. This information is listed on the label and tells users how to utilize that product safely. Home remedies have not gone through this process, and as such there is no safety data or guidance available. This does not mean that a home remedy is inherently dangerous, but that there is no guidance or data to suggest how it can be used safely.

Anytime a pesticide is being used, whether it is registered or not, protecting oneself from exposure is crucial. A registered pesticide gives clear directions on what PPE needs to be utilized, and these requirements are nonnegotiable. If using a homemade pesticide, the same commitment to safety should be taken. The most common route of exposure is exposed skin, with the hands being the most common. Eyes are the most sensitive and responsive to exposure. Therefore, clothing that adequately covers the skin as well as gloves, goggles, and closed-toe shoes are all examples of possible PPE that should be considered. Anytime a pesticide is used, be sure to wash your hands immediately after use and before eating, drinking, or using the restroom. Any clothing that was exposed should be laundered separately from other clothes.

Summary

Anytime a substance is used to manage a pest, regardless of its source, it becomes a pesticide. UF/IFAS recommends the use of EPA-registered products because safety and use information can be clearly found on the label. Any pesticide, registered or homemade, should be used in a manner that limits exposure, and the safety of both the environment and oneself must be considered.

Additional Resources

Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. 2020. Title 40, Chapter I, Subchapter E. Pesticide Programs. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=97a5895fb06ff5db4452500075e9390c&mc=true&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title40/40CIsubchapE.tpl

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2017. "Pesticides Must Be Registered with EPA." https://www.epa.gov/safepestcontrol/pesticides-must-be-registered-epa

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2018. "What Is a Pesticide?" https://www.epa.gov/minimum-risk-pesticides/what-pesticide

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2020. "Pesticides." https://www.epa.gov/pesticides

UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions. 2020. "Soaps, Detergents, and Pest Management." https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/care/pests-and-diseases/pests/management/soaps-detergents-and-pest-management/