Introduction

Although many people are familiar with the sight and smell of mothballs, very few give much thought on how they should and should not be used. Mothballs can be effective at repelling certain insects within the home, but it is important to use them properly. Because they are used within the home and commonly considered a household product, users often fail to read the directions or take these products seriously. For example, individuals mistakenly think mothballs can be used to repel all kinds of pests, even rodents inside or outside the home. Even though they seem to be a general repellant, there is a reason they are called "moth" balls: they are specifically designed and labeled for moths. The purpose of this document is to provide the public with definitions and instructions for proper usage of mothballs.

Why are mothballs needed?

Mothballs are an effective way to repel certain flying insects that are known to eat clothing. The clothes moth, Tineola bisselliella (Figure 1), is the most common culprit for damaging clothes in homes, particularly those that are stored for long periods of time. The advent of synthetic materials for clothes, improved home climate control, and more common and effective pest control tools and tactics have greatly reduced reliance on moth control, particularly with mothballs. However, mothballs, when used according to the label, are still an effective way to reduce the risk of severe damage to clothes when placed in storage. For more information about the life cycle and identification of the clothes moth, see ENY-223, Clothes Moths (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/ig090).

Credit: Top: University of Georgia, Bugwood.org; Bottom: Clemson University—USDA Cooperative Extension Slide Series, Bugwood.org

Are mothballs really a pesticide?

Mothballs are sold with a very specific claim that they repel a pest (moths). Because a pest repellant/control claim is made, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requires registration and creation of a product use label. Many individuals are familiar with mothballs because they are sold in places like grocery stores and are readily available, but they are in fact pesticides and regulated as such.

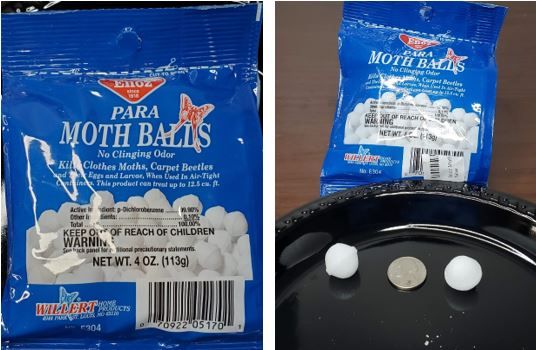

Mothballs, moth flakes, crystals, and bars are insecticides that are formulated as solids (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Mothballs are registered as pesticides because they contain high concentrations of one of two active ingredients—naphthalene or paradichlorobenzene (sometimes referred to as 1,4-dichlorobenzene). There are currently more than 30 products registered with the US EPA that contain paradichlorobenzene and more than a dozen products that contain naphthalene. Paradichlorobenzene is also found in deodorant blocks made for trash cans and toilets. Through a process called sublimation, mothballs slowly convert from a solid into a gas.

Credit: Brett Bultemeier, UF/IFAS Pesticide Information Office

Credit: Brett Bultemeier, UF/IFAS Pesticide Information Office

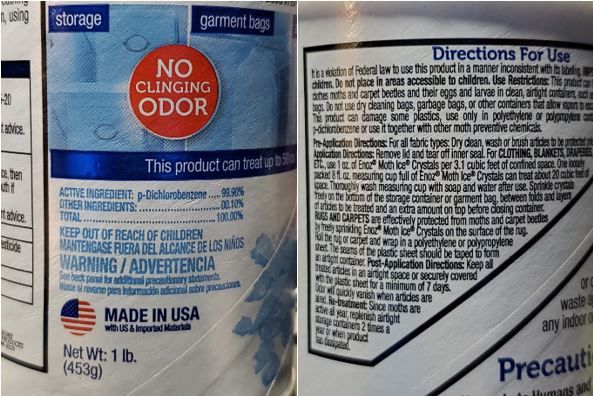

As with any pesticide, the label is the law. The label language is not simply a set of directions. Rather, they are requirements that are legally enforceable. Therefore, the label for mothballs (Figure 4) specifies exactly where and how the product can be legally used. Using mothballs in a way not specified by the label is not only illegal but can harm people, pets, or the environment. The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) frequently receives complaints and investigates the misuse of mothballs. Most misuse involves outdoor placement of mothballs with the mistaken idea that this pesticide will repel snakes and other nuisance wildlife. Some snake and wildlife repellents available at retail stores do contain naphthalene; however, mothball products are not approved for such use, and this practice is illegal.

Credit: Brett Bultemeier, UF/IFAS Pesticide Information Office

Always read the label before you buy and before you use any pesticide. This means reading the entire label contained on any product sold as a "mothball." Mothball containers typically direct the user to place mothballs in a tightly closed container (Figure 5) that will prevent the pesticide fumes from accumulating in living spaces where people and pets can inhale them and become ill. Additionally, the airtight container allows the vapors released by the mothballs to accumulate to toxic levels and kill the targeted pest (moths).

Credit: Brett Bultemeier, UF/IFAS Pesticide Information Office

Can mothballs be harmful to people?

Mothballs can harm people, pets, and wildlife that touch or come into contact with the vapors. Humans are most likely to be exposed to either paradichlorobenzene or naphthalene by breathing in the vapors. Small children and pets are at risk of eating mothballs, because they look like candy or other treats. One mothball can cause serious harm if eaten by a child. As on all pesticides, there is language specifying to "Keep out of reach of children."

Naphthalene is produced when things burn, so naphthalene is found in cigarette smoke, car exhaust, and smoke from forest fires. Once naphthalene enters the human body, it is broken down to alpha-naphthol, which is linked to the development of hemolytic anemia, the abnormal breakdown of red blood cells. As a result, oxygen can no longer be carried in the blood as it should. Kidney and liver damage may also occur. Alpha-naphthol and other metabolites are excreted in urine.

In humans, paradichlorobenzene is distributed in the blood, fat, and breast milk. It is broken down into several other chemicals by the body and excreted in urine. The World Health Organization (WHO) considered paradichlorobenzene possibly carcinogenic to humans based on studies with mice (World Health Organization 2009). The US EPA has classified it as "not likely to be carcinogenic to humans."

What are the signs and symptoms from exposure to paradichlorobenzene and naphthalene?

People have developed headaches, nausea, dizziness, and/or vomiting after being exposed to naphthalene vapors. If someone breathes in enough of the vapor or eats a mothball containing naphthalene, they could develop hemolytic anemia. Small children have also developed diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain, and experienced painful urination with discolored urine after eating naphthalene. Dogs that have eaten naphthalene mothballs may have lethargy, vomiting, diarrhea, lack of appetite, and tremors.

Similar to naphthalene, exposure to paradichlorobenzene can cause nausea, vomiting, dizziness, fatigue, and headaches. Its vapor can also irritate the eyes and nasal passages. If paradichlorobenzene contacts the skin for a prolonged period, it can cause a burning sensation. If a pet eats a mothball made of paradichlorobenzene, they may have vomiting, tremors, and/or abdominal pain. Paradichlorobenzene may also cause kidney and liver damage in pets.

If someone has swallowed a mothball, call the Poison Control Center at 1-800-222-1222 for emergency medical advice. If a pet is suspected of eating a mothball, contact a veterinarian.

What happens to naphthalene and paradichlorobenzene in the environment?

Most of these chemicals will turn into a gas. In air, the half-life of naphthalene is very short, often less than one day. Paradichlorobenzene can persist up to 31 days.

Some naphthalene may be bound to soil or broken down by bacteria, fungi, air, and sunlight. There is no information available on naphthalene and groundwater, although it is not very soluble in water.

Paradichlorobenzene that binds to soil may be taken up by plants, and plant leaves may absorb it from the air. Paradichlorobenzene has been found in rainwater and snow and in groundwater close to a source of contamination. It is considered moderate to low in toxicity to fish, with differences in sensitivity by species.

Conclusion

Naphthalene and paradichlorobenzene, the active ingredients in mothballs, are registered pesticides. This means that mothballs are pesticides. As such, it is important to read and understand the label before you buy and before you use these, or any, pesticides. Failure to follow the label directions could not only cause legal trouble, but also harmful effects on people and the environment. Only use registered pesticides in the manner they are intended to ensure proper efficacy and safety. Mothballs are easy to find and purchase, but they are still pesticides and must be treated as such.

Additional Information

Fishel, F. M. 2006. Homeowner's Guide to Pesticide Safety. PI-174. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/pi051

Fishel, F. M. 2012. How to Report Pesticide Misuse in Florida. PI241. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Archived.

Vazquez, R. J., P. G. Koehler, and R. M. Pereira. 2017. Clothes Moths. ENY-223. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/ig090

World Health Organization. 2009. The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 2009. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547963