Biology

The northern raccoon, Procyon lotor, is the species in North and Central America, and the related crab-eating raccoon, Procyon cancrivorus, occurs from Panama to Argentina. They are in the family Procyonidae along with the coati mundi, kinkajou, ringtail, and olingo. Raccoons are found commonly in every one of the lower 48 states, in much of southern Canada, and throughout Mexico and Central America. Raccoons are very adaptable animals and thrive in all kinds of habitats from the desert southwest to tropical forests and northern hardwoods. Unlike many wildlife species, raccoons do especially well in urban areas.

The northern raccoon, Procyon lotor, is known in many parts of the world. This is one animal that most people are well-acquainted with wherever it occurs because of its large size, abundance, ecological success, and often its nuisance behaviors. It is usually just called raccoon or "coon" in English; malpache norteno, malpache boreal, malpachin, osito lavador in Spanish; and guaxinim in Portuguese. In native American languages they are called tzil (Mayan), mapachitli (Aztec), kvtli (Cherokee or Tsalagi), ati:ron (Mohawk), esiban (Algonquin), eehsipana (Miami-Illinois), nahënëm (Lenape Delaware), sawa (Alabama), sawá (Koasati), shaui (Choctaw), shawi' (Chickasaw), and wotko (Muskogee). In areas it has colonized in Eurasia it is called waschbär (German), wasbeer (Dutch), orsetto lavatore (Italian), araiguma (?????) (Japanese), raton laveur (French), tvättbjörn (Swedish), pesukarhu (Finnish), and mosómedve (Hungarian). Many of these names are local translations that mean the "washing bear."

Raccoons are found statewide in Florida in ever-increasing numbers. Urbanization and agriculture often help their population because food becomes more available in these conditions. Exotic fruit and ornamental plants provide a greater diversity of food in human-managed landscapes. Therefore, it is not at all uncommon to encounter raccoons near your home or neighborhood.

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

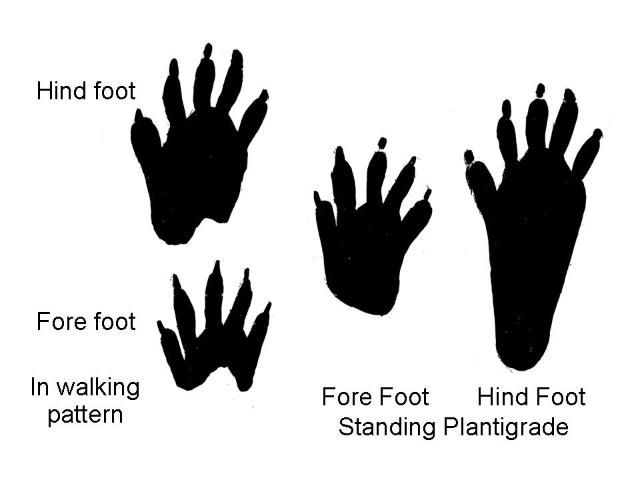

There is no mistaking a raccoon for any other animal. Its stout, bear-like body, prominent black mask, and heavily furred, ringed tail all are distinctive. Adult raccoons are about 2 to 3 feet long (including their 10-inch tail) and weigh anywhere from 10 to 30 pounds. Larger animals sometimes have been recorded, but Florida raccoons tend to be smaller than those occurring farther north. Their color generally is a grizzled salt-and-pepper gray and black with a light gray belly. Often the "white" hairs are noticeably yellowish. Both all-black and all-white animals sometimes occur. Males are called boars, females are called sows, and young are called kits.

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Raccoons are active mostly during the evening hours. On most days, they leave their dens soon after dusk and are active until morning. It is not unusual, however, for them to linger in their dens well past nightfall, and during particularly nasty weather they may not venture out at all. Raccoons are adaptable, however, and it is therefore not uncommon or unusual to see one foraging during the day. This is because midday is often the quietest time in suburban neighborhoods, with people at work and school, and dogs confined inside houses. Seeing a raccoon out during the day does not mean it is rabid or dangerous.

Individual raccoons normally use a home range of 1 to 3 square miles and are somewhat territorial, especially the males. Raccoons seen in small groups most likely are females with young or unassociated adults from neighboring territories brought together by a large food source. Raccoons may travel more than a mile from their home range to feed on a locally plentiful food. They can tolerate severe reductions in territory size if enough food and shelter exist. Raccoon densities of 100 per square mile can be attained around abundant food sources, especially coastal and wetland habitats.

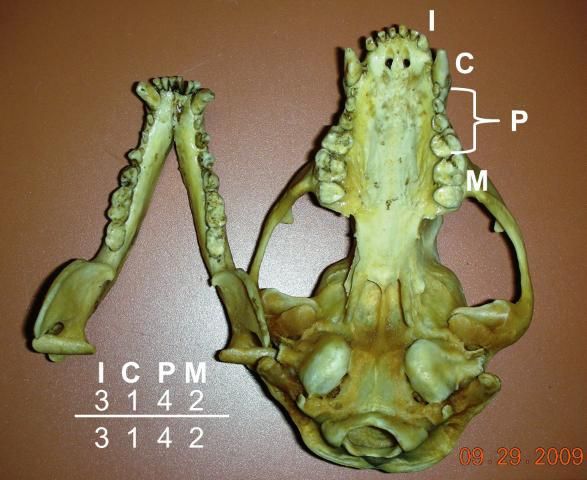

Raccoons are not fussy about their choice of food. Although classified as a carnivore, the raccoon eats as much or more plant as animal matter during the year. When fruits, acorns, and seeds are ripe and available, raccoons will feed heavily on them. At other times and places they will specialize on bird and turtle eggs, insects, crayfish and crabs, frogs, fish, and small mammals. They'll eat dead animals that they encounter; they'll raid bird feeders for seed and pet food bowls; and they'll check out garbage cans that aren't secured. Raccoons will prey on small pets and livestock if they have access to them; rabbits in hutches, pet birds caged on porches, and poultry in pens have all fallen prey to these clever foragers.

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Raccoons are not fussy about their living quarters. Under normal conditions, they usually select a den in a hollow tree, usually a large limb instead of the trunk. Dens in trees may be anywhere from ground level to 60 feet above ground. In urban and other areas lacking tree cavities, raccoons choose a wide variety of "cavities," including rock and debris piles, attics, crawl spaces beneath homes, decks, sheds, culverts, sewer drains, and the burrows of other animals.

Breeding occurs first when raccoons are one year old. Normally, one litter is born each year. In Florida, this generally occurs in March and April. Litters average about 3 to 4 young, though as many as 7 have been recorded. Newborn raccoons' eyes remain closed until they are about 20 days old. They are weaned at 10 to 12 weeks, but the offspring may stay with their mother until they are 10 months old.

Raccoons have few natural enemies left in Florida other than man. A few are killed by predators such as alligators, dogs, coyotes, bobcats, and great horned owls, but their traditional predators, such as panthers and red wolves, have largely disappeared. The coyote, which has become established in Florida over the last few decades, preys on raccoons, but it is uncommon in the suburban areas where raccoons thrive. Large alligators, over 8 feet long, are important raccoon predators near water. Their presence around bird rookeries helps to limit raccoon predation on nests and roosting birds at night. Due to fear of alligators, the public often wants most large animals removed by trappers before they are even large enough to prey on adult raccoons. Even humans have largely stopped hunting raccoons for food and hides. Automobiles likely kill more raccoons than all natural predators combined.

The greatest concern with raccoons is disease. Raccoons are known to carry a wide variety of diseases and parasites. Most of these are not dangerous to them or people, but a few are deadly. Distemper and rabies will kill raccoons if they become infected. When raccoon populations get too dense, an epizootic (the animal equivalent to an epidemic in people) can occur. Epizootic outbreaks among raccoons can become a problem for people because raccoon diseases can infect unvaccinated pets. The risk of rabies is small (less than 1 out of 200 raccoons in the wild has been exposed to rabies), but the risk should never be taken lightly. Raccoons are wild animals and should never be treated as pets. A wildlife rabies vaccination program has been implemented in several counties in Florida. A live vaccine is distributed to raccoons, foxes, feral dogs, and feral cats in a fish meal block. The animal bites the block, and the liquid vaccine squirts into its mouth. The virus in the vaccine is not rabies, but a genetically modified virus containing the gene for the rabies coat protein. It produces an immune response to that coat protein and the animal is immunized against rabies.

Solving Raccoon Problems

Raccoons are one of our most successful urban animals and are, therefore, frequently observed in our yards and around our homes. This should not by itself be cause for alarm. Under most conditions, raccoons are harmless, interesting neighbors and should be treated as part of the natural community. You will occasionally get a glimpse of one going about its business, and these can be fascinating times. Problems with raccoons often arise because we find it so difficult not to "do something" for them.

Feeding raccoons is one such case. Because they eat just about everything imaginable, raccoons are almost never in danger of starving--especially in Florida's mild climate. Even in urban landscapes, raccoons find plenty to eat. By putting food out for them, we condition them to lose their "respect" for people--a trait that aids greatly in their ability to survive. Feeding animals also causes local populations to become denser than the habitat can adequately support. At these times, raccoons begin to look more closely at your home to provide them shelter, and they are more likely to become ill and transmit diseases. If welfare of the animals isn't enough to stop you from feeding them, remember that it is illegal! Under Florida Administrative Code 68A (4.001), it is illegal to feed bears, foxes, raccoons, and sandhill cranes. As of June 2002, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission will enforce this rule with penalties including 60 days in jail and fines up to $500.

68A-4.001. General Prohibitions.

(3) Intentionally placing food or garbage, allowing the placement of food or garbage, or offering food or garbage in such a manner that it attracts black bears, foxes, or raccoons and in a manner that is likely to create or creates a public nuisance is prohibited.

Types of Problems and Control Techniques

Raccoon problems are varied, but most can be divided into 2 major categories. Both of these are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Feeding Around Homes

Raccoons often become a nuisance because of their feeding habits. When this occurs, your best strategy is to prevent their access to food. If raccoons are raiding your pet's food dish, feed your pet during daylight hours and remove the uneaten food before dusk. If raccoons are raiding your garbage can, then make the can inaccessible. Get a raccoon-proof garbage can or weight the lid so that they can't open it. Keep your garbage cans in the garage or build a bin with a latchable lid to store them.

Eating Crops

Many other raccoon feeding problems, however, are not as easily solved and are not directly tied to feeding them. Everyone who has ever tried to grow sweet corn and other fruits and vegetables with a raccoon in the area has likely lost a good share of their potential harvest. Raccoons can be quite frustrating to fruit and vegetable growers. Solving these problems can be equally frustrating. Be aware that repellents of any kind (including mothballs) and scare devices will not be successful. No raccoon in the world will pass up the opportunity to dine on something ripe and delicious simply because there is a strange odor or object nearby. One method that will work is to prevent access. A single strand electric fence with the wire 8 inches above the ground won't harm the animals physically and can do wonders to keep them out of the garden. The only other method is to remove the animal from your yard by means of a live trap. It is illegal to release raccoons on any county, state, or federal property or on private property without the property owner's permission.

Living in the Attic (or Elsewhere in the House)

Perhaps the greatest problem with raccoons occurs when they set up housekeeping inside your residence. Raccoons often come into an attic or crawl space when an entry point to the outside is not maintained or repaired. Torn screens or soffits, open chimneys or broken windows are common entry points. They also may take up residence beneath your mobile home or deck. Once a raccoon has moved in, it is difficult to cause it to leave. Chasing the animal out somehow and then sealing off the entry hole seems reasonable, but in fact frequently causes even more damage because the raccoon often returns and forces its way back in. This is especially true of mothers with young. Females (sows) with young (kits) can sometimes be encouraged to move their young to another den site by placing cotton balls or strips of cloth soaked with male raccoon urine or other predator urine in the attic or crawl space. Raccoon urine can be found in sporting goods stores or online. It is used as a cover scent by deer hunters. Fox or coyote urine is sold as a repellent for deer or rabbits in the garden and as a trapping lure for these animals. These urines can be purchased from garden or trapping suppliers on line. There are one-way devices that allow the animal to leave but not get back in. This is useful for males and females without young. Physically removing the nuisance raccoon with a live trap and euthanizing it is the least desirable but often the ultimate solution to this problem. Exclusion and prevention are always the cheapest and simplest ways to control nuisance wildlife situations.

Defecating in Swimming Pools

A raccoon defecating on the steps of the swimming pool is a common complaint from homeowners. Standing in shallow water to defecate is natural for raccoons. It is a way for them to hide their droppings from other raccoons and predators. To prevent this unpleasant behavior, cover the top couple of pool steps with a plastic sheet or plastic panels to deny them access. Raccoons will not jump into deep water and swim merely to poop on a step. They will find a more convenient way to hide the smell of their droppings, often going to your neighbor's pool or decorative pond.

Credit: George Schneider, UF/IFAS

Raccoon Digging up New Plantings

Raccoons can smell disturbed soil and will investigate it to look for turtle eggs or other food. You can deter them by adding naphthalene wildlife repellent or cayenne pepper to the disturbed soil around the new plant. While mothballs also contain naphthalene, mothballs are not labeled for use outside. Use of a pesticide not in accordance with the label is a violation of Florida Pesticide Law and the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act.These repellents are temporary, but once the smell of newly disturbed soil dissipates, the raccoons lose interest. This usually takes 3–4 days (or nights).

Live-Trapping

Check your local ordinances before attempting to trap raccoons. If you are legally able to release the trapped raccoon, you also will want to determine where it would be legal to release it and obtain permission beforehand. The release site should be at least three miles from your property or the raccoon likely will return. Raccoons that are causing property damage may be live-trapped without a permit from the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission (GFC), but if the raccoon is to be taken away from your property and released, a Raccoon Relocation permit is required.

Setting a live trap to remove a problem raccoon is relatively easy, but to achieve the desired results you've got to set it correctly. Traps should always be set where they can be monitored easily. Never place the trap in an attic or under a mobile home unless it's absolutely necessary and you can check it at least daily. It is far preferable to put the trap in the raccoon's normal path of travel or in an open place where it is known to be feeding.

Bait the trap either with something that the raccoon is currently feeding on or with something that will surely tempt it. This is not too difficult because raccoons will eat virtually everything. In most cases, a dry cat food that includes fish meal is an inexpensive, non-messy, excellent choice. Raccoons can be very easy to lure into a trap, but at other times they are exceptionally frustrating. Try switching baits if the raccoon will not enter your trap after the first 3 or 4 nights. Chicken necks, an ear of sweet corn, or whole peanuts are some of the varied foods that might tempt your problem animal. If switching baits does not produce results, you will have to reduce the raccoon's fear of the trap. Wire the door of the trap open so it cannot fall shut. Then place bait both inside the trap and around the outside. After a few days, the raccoon probably will begin to enter the trap to feed. Once it is doing this regularly, you can unwire the door.

One final consideration is your choice of trap. Although there are many brands of live traps, they all work much the same. One difference, even among the same brand, is the number of doors available. When trapping raccoons, traps that open at only one end are preferable to those that open at both ends. If you are using a two-door trap, consider closing one of the doors and locking it down, thus making it a one-door trap. This forces the raccoon to go all the way to the back of the trap to reach the bait, which ensures that it will be trapped when the door is triggered.

Because relocated raccoons may spread disease to the resident raccoon population and because they frequently cause other problems, it is recommended that live-trapped raccoons be humanely euthanized. CO2 chambers are a simple, safe, and humane method of euthanasia, and the meat is still fit to eat if you so choose. Drowning is not considered humane euthanasia.

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Other Control Methods

Raccoons are protected by various rules administered by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. It is legal to kill a nuisance raccoon if you hold a valid hunting license when it is done by a humane method. The use of poisons and leghold or body gripping traps are not legal without a permit and are not recommended for raccoons. Check local ordinances before using any lethal control method. Never discharge a firearm inside city limits or in residential areas.

Credit: William Kern, UF/IFAS

Recommended Additional Material

Boggess, Edward K. 1994. RACCOONS. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management. http://icwdm.org/handbook/carnivor/Raccoons.asp

Hadidian, John; Margaret Baird; Maggie Brasted; Lauren Nolfo-Clements; Dave Pauli; and Laura Simon; Shane Dimmick (Illustrator). 2007. Wild Neighbors: The Humane Approach to Living with Wildlife Second Edition. Humane Society Press. 283 pp.

Hygnstrom, Scott E.; Robert M. Timm; and Gary E. Larson. 1994. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management. http://icwdm.org/handbook/index.asp

Lopez, Andrea Dawn. 2002. When Raccoons Fall through Your Ceiling: The Handbook for Coexisting with Wildlife (Practical Guide Series, 3). University of North Texas Press. 184 pp.