Introduction

This publication series is geared toward leaders who face having difficult conversations in their professional roles. For the purposes of this Leading Difficult Conversations series, difficult conversations are described as conversations where two or more individuals have opposing opinions, strong emotions are present, and the stakes related to the outcome are high (Patterson et al., 2012). Earlier in this publication series, the following principles of preparing for difficult conversations were established: (1) defining the issue, (2) determining your motive for the conversation, and (3) creating a safe conversation environment.

This publication focuses on helping leaders better understand their communication style when under stress. Even with adequate preparation, difficult conversations can still be stressful. By understanding their communication style under stress, leaders can better regulate their personal responses to ensure a productive conversation.

Understanding Communication Styles

Effective interpersonal communication is a core component of leadership (Kuria, 2019). Just as personality styles differ among individuals, everyone has a unique communication style as well. Communication style is defined as the “characteristic way a person sends verbal, paraverbal, and nonverbal signals in social interactions denoting who he or she is or wants to appear to be, how he or she tends to relate to people with whom he or she interacts, and in what way his or her messages should usually be interpreted” (DeVries et al., 2009, p. 179).

Effective communication and leadership abilities are critical in today’s workforce, and the study of one’s personal leadership communication styles is important to grow professionally (Rogers, 2012). One way for leaders to better comprehend their communication style is to understand how their style is influenced by stress. By understanding how communication styles are influenced by stress, a leader can become a “vigilant self-monitor” (Patterson et al., 2012, p. 63). Self-monitoring is important because it increases the leader’s ability to manage their own emotions to ensure professionalism and politeness remain throughout the conversation” (Farrell, 2015).

Silence and Violence Spectrum

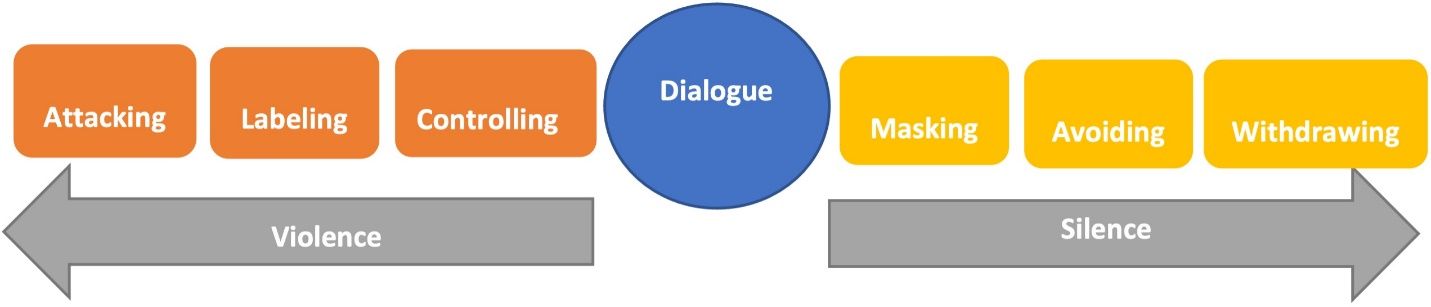

Often difficult conversations cause stress levels to increase. When stress is introduced into the conversation, individuals tend to fall within a reaction spectrum of silence to violence (Patterson et al., 2012). Silence is described as intentionally withholding information through various methods such as masking, avoiding, and withdrawing, while violence is described as forcefully trying to make others agree. Violence tactics include controlling the conversation, labeling others, and attacking others (Patterson et al., 2012).Regardless of the tactic used, all these reactions move the conversation further away from dialogue.

Additional descriptions of each communication style under stress include:

Silence Reactions

- Masking is seen when individuals employ sarcasm or sugarcoating within a conversation. Masking refers to selectively sharing one’s true feelings about the issue at hand.

- Avoiding refers to refusing to engage in a difficult conversation. Individuals may still engage with others, but they will not discuss certain topics that could create challenging conversations.

- Withdrawing occurs when an individual physically leaves the space or abruptly leaves the conversation and topic.

Violence Reactions

- Controlling is domineering the conversation. Common tactics include overstating facts, speaking in absolutes, and changing the subject to force others to agree.

- Labeling is an attempt to stereotype another person to undervalue their opinion or perspective. Individuals who label are attempting to discount who the person is as a tactic to undermine what the person is saying.

- Attacking is seen when an individual’s conversation tactics move to threatening or belittling the other speaker (Patterson et al., 2012).

While these styles under stress are not flattering behaviors, understanding one’s tendencies can serve as a productive leadership tool. The organization Crucial Learning has an excellent resource to assist leaders in determining their communication style under stress. The survey below is a tool to assist in determining a leader’s communication style under stress.

Directions: Click on this link to take a short assessment to determine your typical communication style under stress: Style under Stress Assessment

Managing Your Communication Style under Stress

The results from the Communication Styles under Stress Assessment can be used to assist leaders in recognizing which end of the silence/violence spectrum they tend to move toward during stressful situations. Once a leader recognizes their style under stress, they can develop strategies to ensure their communication style continues to promote dialogue even in times of stress. The following strategies can be used to promote productive dialogue:

- Stay Present

During a conversation, when you notice your body beginning to give you emotional or physical cues pushing you toward silence or violence, internally commit to staying present during the conversation. One tangible way to stay present is to utilize self-talk or a visual cue. When you feel emotional or physical signals indicating stress happening, concentrate on someone or something that brings peace to you. Hamilton (2015) explains that when she is in a tough conversation, she reminds herself of her son and the funny way he tells her to calm down when she gets frustrated. This reminder helps her to stay present in the conversation.

- Manage Your Emotions

We cannot control what others say or do. We can only control how we respond. Emotions occur when we add meaning to the words we heard or the actions we observed. Sometimes we add meaning to words or actions that the speaker never intended. Leaders can manage their emotions by determining if there are facts to support the emotion they are feeling. Facts are “specific, objective and verifiable” (Patterson et al., 2012, p. 115).

For example, during a difficult conversation, you notice your direct report keeps looking down at his phone during the conversation. At first, you want to get angry because this action must mean he is not taking the conversation seriously. However, instead of becoming frustrated by his action, you decide to ask him about this specific behavior. He shares with you that his mother is having surgery today and he is anxiously waiting for an update. Addressing the facts in a situation may lead to uncovering new information that could impact the conversation.

- Stay Focused on What You Really Want

When emotions run high, it can be tempting for leaders to focus on the emotion they are feeling instead of the outcome they desire. When emotion and stress enter the conversation, leaders must remind themselves to continue to pursue the “elusive and,” which refers to defining the outcome they want and the outcome they do not want (Patterson et al., 2012, p. 46). For example, a leader who must address a performance issue with a direct report may want to address poor performance but does not want the employee to feel disrespected. In this case, if the conversation becomes emotional, it could be helpful for the leader to remember their intended goal: “My goal is to have an honest conversation with Mary about her poor work performance and treat her with respect.” Staying focused on the desired outcome is an important method to avoid potentially being distracted by emotions.

Summary

Leaders are not immune from feeling stress during difficult conversations. By understanding default tendencies under stress, leaders can begin to employ strategies to mitigate behaviors not conducive to dialogue. Committing to staying present, managing emotions and remaining focused on the intended outcome are strategies to use to overcome being controlled by silence or violence communication styles in a stressful conversation.

References

Crucial Learning. (2021, August 30). Style under stress 12 assessment. Crucial Learning. Retrieved September 17, 2021, from https://cruciallearning.com/style-under-stress-12-assessment/

De Vries, R. E., Bakker-Pieper, A., Robert, A. S., Kim, V. G., & Martijn, V. (2009). The content and dimensionality of communication styles. Communication Research, 36(2), 178-206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208330250

Farrell, M. (Column Editor). (2015). Difficult conversations. Journal of Library Administration, 55(4), 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1038931

Hamilton, D. M. (2015). Calming your brain during conflict. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/12/calming-your-brain-during-conflict

Kuria, G. N. (2019). Literature review: Leader communication styles and work outcomes. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 10(1), 1956–1965.

Patterson, K., Grenny, J., McMillan, R., & Switzler, A. (2012). Crucial conversations: Tools for talking when the stakes are high. McGraw-Hill.

Rogers, R. (2012). Leadership communication styles: A descriptive analysis of health care professionals. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 4(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S30795