Overview

A key responsibility for 4-H agents has been to engage volunteers and expand their involvement in 4-H programs (Schmiesing & Safrit, 2007). There are a number of functions that a 4-H agent must fulfill to successfully involve volunteers in his or her county program. This article will provide an overview of these functions, including a historical perspective of volunteer involvement in UF/IFAS Extension, the role of the 4-H agent as an administrator and trainer of volunteers, risk management, and a process for managing volunteers.

Extension Volunteers

Volunteers are an essential component of Extension programs and provide nonformal education to clientele who otherwise might not be served (Boyd, 2004). They are vital to Extension programming and are key to accomplishing local, state, and national initiatives (Sinasky & Bruce, 2007). Volunteers contribute to learning environments by carrying out many roles and filling positions that both directly and indirectly impact Extension's clientele (Boyce, 1971). Volunteers have historically been involved in UF/IFAS Extension in three primary functions: advisory, education delivery, and program support.

Advisory

All Extension programs are required to have a program advisory committee made up of volunteers. A portion of a county faculty member's annual appraisal is related to advisory committee involvement. Program advisory committees provide benefits to Extension programs such as:

- Identifying needs/issues within a community or county

- Advising or recommending on how best to reach target audiences

- Advocating for Extension programs and UF/IFAS Extension (PDEC, 2014)

Education Delivery

Another common program function of volunteers is education delivery in roles such as 4-H club leader. In county Extension offices across Florida, volunteers lead clubs and deliver educational programs to youth. In addition, many of these volunteers help county faculty train and mentor other club volunteers in the program. Each year in 4-H, more than 15,000 volunteers support the 4-H program in Florida by providing learning opportunities for youth in community clubs, classrooms, residential camps, and other events and activities.

Program Support

Finally, volunteers serve in Extension program support functions. These could include the following:

- Fundraising

- Marketing the program, including writing articles in newspapers, preparing newsletters, and speaking to industry groups and other organizations

- Coordinating and managing events and opportunities for clientele

- Recruiting new volunteers to become involved in Extension

The factors limiting volunteer involvement in program support roles are the ability to identify a role that needs a volunteer, creating a compelling reason for a volunteer to fulfill the role, and agent capacity to properly train and support volunteers.

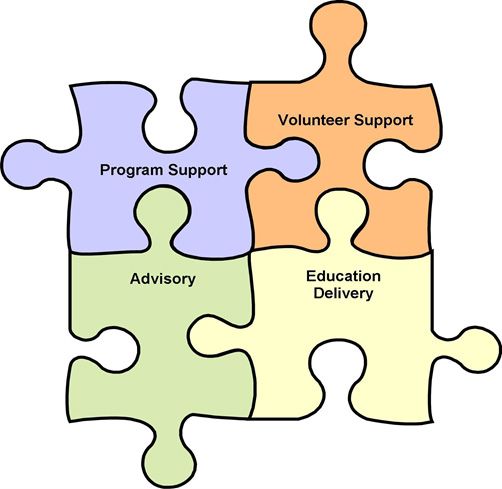

Volunteer Roles in 4-H Programs

One way to think about volunteer management within county 4-H programs is through a puzzle (Figure 1). The square represents the overall goals and objectives of the 4-H program. The puzzle pieces represent the various educational activities and program tasks that need to be completed to achieve the goals and objectives. As the 4-H agent, the goal is to design and shape these individual pieces in concert with both the staff and volunteers.

Credit: undefined

Integrating Volunteer into 4-H Programs

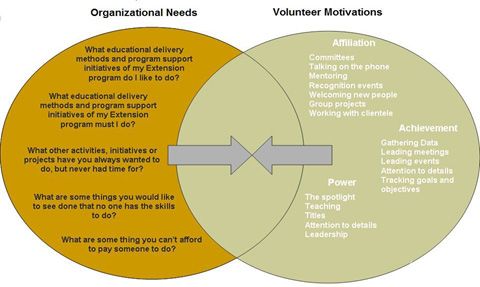

Another key aspect of involving volunteers can be illustrated using overlapping circles (Figure 2). One circle represents the needs of the 4-H program. Ask these questions:

- What educational delivery methods and program support initiatives of the 4-H program that need to be accomplished are not being done?

- What other activities, projects or initiatives are not imperative, but would enhance the quality of the 4-H program?

- What are some things that need to be done, but no paid staff has the skills to do?

- What are some things that resources are not available to pay someone to do?

The answers to these questions can form the basis for defining volunteer roles that can be integrated into the 4-H program. The keys are to bring in volunteers to complement staff in delivering education or providing program support that adds value to 4-H, and to empower volunteers to take on projects that address unmet community needs. Doing so extends the effectiveness of Extension programs and facilitates a positive relationship between staff and volunteers.

The other circle represents what volunteers are willing and able to do. What volunteers are willing to do is related to their motivations. The development of the Volunteer Motivation Inventory (VMI) describes ten key categories of volunteer motivation based upon research of more than 2,400 volunteers from 15 different nonprofit organizations (Esmond & Dunlop 2004). These categories are:

- Values—Describes a situation where a volunteer is motivated by the firmly held belief that it is important to help others.

- Recognition—Describes a situation where a volunteer enjoys the recognition that volunteering gives them. They enjoy recognition of their skills and contributions, and that motivates them to volunteer.

- Social Interaction—Describes a situation where a volunteer particularly enjoys the social atmosphere of volunteering. They enjoy the opportunity to build social networks and interact with other people.

- Reciprocity—Describes a situation where a volunteer enjoys volunteering and views it as an equal exchange. The volunteer has a strong understanding of the “higher good.”

- Reactivity—Describes a situation where a volunteer is volunteering out of a need to heal or address their own past issues.

- Self-Esteem—Describes a situation where a volunteer seeks to improve their own self-esteem or feelings of self-worth through their volunteering.

- Social—Describes a situation where a volunteer seeks to conform to normative influences of significant others (e.g., friends or family).

- Career Development—Describes a situation where a volunteer is motivated to volunteer by the prospect of gaining experience and skills in the field that may eventually be beneficial in assisting them to find employment.

- Understanding—Describes a situation where a volunteer is particularly interested in improving their understanding of themselves, the people they are assisting, or the organization for which they are a volunteer.

- Protective—Describes a situation where a volunteer is volunteering as a means of escaping negative feelings about themselves.

These categories can be further grouped into affiliation, achievement, and/or power motives (McClelland, 1987).

The power motive causes a person to desire control or influence over another person or group. People motivated by power do things in order to draw attention to themselves. Volunteers motivated by power may satisfy this need through leadership roles.

Another major motive is the affiliation motive. An individual with an affiliation motive will act in order to enjoy mutual friendship. Affiliation motivation is defined as establishing, restoring, or maintaining a close, warm, friendly relationship with another or others, or being emotionally concerned over separation from someone else (McCurley and Lynch, 2006). Volunteers with a high affiliation motive spend more of their time interacting with others than do people with weaker affiliation motives. Mentoring and group projects are excellent roles for volunteers with affiliation motivations.

Volunteers with achievement motives will act in ways that will help them to outperform someone else, meet or surpass some standard of excellence, or do something unique. Definitions of what constitutes achievement differ, but what is constant across these achievers is the notion of doing something better.

Volunteers, as achievers, prefer working on moderately difficult tasks and are drawn to work in situations where they take personal responsibility for their performance. Such work might include coordinating and managing events, gathering data, or leading meetings.

Credit: Terry, B., Godke, R., Heltemes, W., & Wiggins, L. (2010)

Another aspect of this illustration is that a volunteer must be capable of performing or learning to perform their assigned role. A key to sustaining a volunteer program is the ability to match the interests, skills, and abilities of a potential volunteer with an appropriate role in the Extension program. This is represented where the two circles overlap.

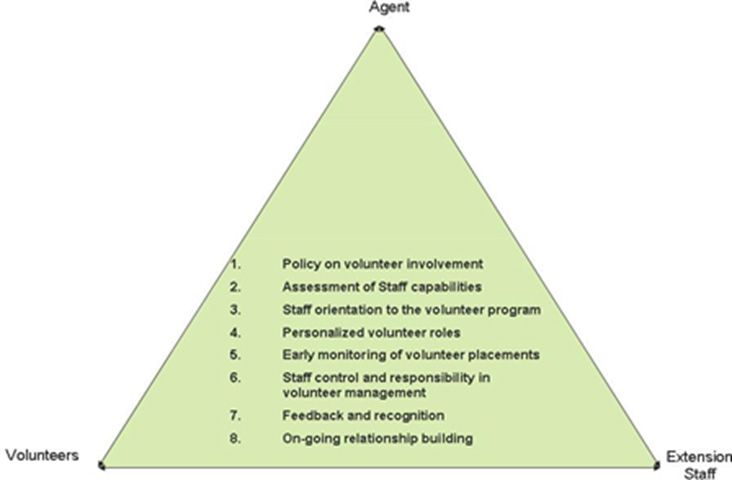

Managing a 4-H Program

Today's volunteers are highly integrated into Extension. In fact, volunteers often fill roles that have previously been performed by paid staff. Many times volunteers will work more closely with staff than with the 4-H agent. This dynamic requires that the volunteer administrator be linked to both volunteers and the staff, which is displayed visually in Figure 3. A key role is ensuring that the needs and concerns of staff working with volunteers are addressed, while at the same time empowering volunteers into expanded roles within Extension.

Credit: Terry, B., Godke, R., Heltemes, W., & Wiggins, L. (2010)

This can be accomplished by communicating the following to 4-H volunteers:

- Policy on volunteer involvement

- Assessment of staff capabilities

- Staff orientation to the volunteer program

- Personalized volunteer roles

- Early monitoring of volunteer placements

- Staff control and responsibility in volunteer management

- Feedback and recognition

- Ongoing relationship building

- Risk management

An important consideration in working with volunteers is reducing risk primarily to clientele, but also to volunteers, faculty, staff, and UF/IFAS. There are a number of policies, procedures, and regulations that have been established to protect volunteers and the organization.

General

The regulation for the University of Florida that covers volunteers is found in section 3.0031. This regulation outlines the definition of who is a volunteer, stating:

A volunteer is any person who, of his or her own free will, provides services to the University with no monetary compensation, on a continuous, occasional, or one-time basis.

Volunteers must be at least 14 years old. All volunteers, including youth volunteers, must complete a volunteer application. For youth, this application must be signed by their parent or guardian.

Youth Protection, Volunteer Screening, and Selection

To protect youth involved in Extension programs, the University of Florida, through regulation https://regulations.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/30031.pdf, has established a volunteer screening https://hr.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/volunteer-policy.pdf. UF/IFAS policy applies this policy to all volunteers who want to work directly with youth (who are not their own children) on an ongoing basis or at an overnight event. Furthermore, volunteers serving more than 10 hours a month or chaperoning minors are required to complete a level 2 screening. Refer to the 4-H Agent Guide (Toelle, Kent, & Cooney, 2020) for managing the approval, denial, screening, and releasing of volunteers in Florida 4-H for a complete walk-through of the 4-H volunteer onboarding process.

This policy is designed for protecting youth participants by implementing risk management practices. The policies further protect volunteers by establishing and communicating policies that reduce risk in specific situations. Finally, the policy protects UF/IFAS Extension faculty and staff by establishing consistent guidelines for structure and behavior.

A Process for Managing Volunteers

Volunteers fulfill many of the same roles and functions as paid staff, and as such, these guidelines should be followed when involving volunteers. When administering and managing unpaid staff, utilize approaches designed to engage and empower volunteers. Florida uses the ISOTURE model for managing volunteers. ISOTURE is a nationally recognized leadership model for volunteers that encompasses the same concepts that would be used to hire new employees. Each letter in ISOTURE refers to a building step for volunteer success:

- Identification of how volunteers will be involved in the Extension program

- Selection of the most appropriate volunteer for a volunteer role through effective recruiting strategies and screening

- Orientation of volunteers to Extension and their specific duties

- Training volunteers and staff to increase their capacity

- Utilization of volunteers through empowerment

- Recognition of volunteers for their contributions

- Evaluation of volunteers by focusing on results (Boyce, 1971)

The saying “there is no such thing as a free lunch” is very fitting for volunteer programs. Volunteers are not free. In addition to the financial commitment that is often made to volunteer programs, involving volunteers requires a huge investment in time and energy. In addition, the costs associated with the inability to retain volunteers are high: ~$1,200 per volunteer lost (Esiner et al., 2009).

Where to Start

Do not expect to accomplish everything at once, so don't try. Begin by getting to know the status of the existing 4-H program. Start by reviewing all current volunteer files to assure they are up to date. Once completed, prepare to implement the Identification part of the ISOTURE model.

Conclusion

Expanding volunteer involvement can be an effective strategy in meeting the goals and objectives of an Extension program. To do so, understand the role in administering and managing volunteers. Use the three geometric figures to help understand the 4-H agent's role as a volunteer administrator. Be aware that there are a number of policies and procedures for working with volunteers. Florida 4-H uses the ISOTURE model because the model is a well-established strategy to expand volunteer involvement in Extension programs.

Understanding the role of a volunteer administrator, knowing and following UF/IFAS volunteer policies and procedures, and utilizing management approaches designed for volunteers will increase the net benefits of volunteer involvement in an Extension program as well as increase the satisfaction of your volunteers.

References

Boyce, M. V. (1971). A systematic approach to leadership development. Washington, DC: USDA, Extension Service. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 065 793).

Boyd, B. L. (2004). Extension agents as administrators of volunteers: Competencies needed for the future. Journal of Extension, 42(2), 2FEA4. https://archives.joe.org/joe/2004april/a4.php

Eisner, D., Grimm, R., Jr., Maynard, S., & Washburn, S. (2009). The new volunteer workforce. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2009. https://doi.org/10.48558/ya69-2r58

Esmond, J., & Dunlop, P. (2004). Developing the volunteer motivation inventory. Perth: Lotterywest & CLAN WA Inc.

McClelland, D. C. (1987). Human motivation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McCurley, S., & Lynch, R. (2011). Volunteer management (3rd ed.). Ontario: Johnstone Training and Consultation, Inc.

Schmiesing, R., & Safrit, R. (2007). 4-H youth development professionals' perception of the importance of and their current level of competence with selected volunteer management competencies. Journal of Extension, 45(3), 3RIB1. https://archives.joe.org/joe/2007june/rb1.php

Sinasky, M., & Bruce, J. (2007). Volunteers' perceptions of the volunteer management practices of County Extension 4-H educators. Journal of Extension, 45(3), 3TOT5. https://archives.joe.org/joe/2007june/tt5.php

Toelle, A., Kent, H., & Cooney, S. (2020). 4-H agent guide for managing the approval, denial, screening and releasing of volunteers in Florida 4-H. EDIS, 2021(6).

UF/IFAS Extension Program Development and Evaluation Center (PDEC). (2014). Advisory committees: A guide for UF/IFAS Extension faculty. https://extadmin.ifas.ufl.edu/media/extadminifasufledu/Extension-Advisory-Handbook-2015.pdf

University of Florida. (2016). Regulations of the University of Florida: 3.0031 Volunteers. https://regulations.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/30031.pdf

University of Florida. (2021). Volunteer Policy. https://hr.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/volunteer-policy.pdf