Enterprise budgets are effective planning tools for growers. They can assist with forecasting as well as help managers coordinate resources, make production decisions, carefully examine expenditures, and anticipate outcomes from changes in production practices. Once established, they become a standard for monitoring what happens in the operation. Enterprise budgets estimate revenues and expenses for a specific farm enterprise (product or commodity); they are constructed on a per-unit-of-production basis for one production cycle (or growing season) and can be used to compare the profitability of alternative enterprises, assist in development of a marketing plan, negotiate with sources of credit, and plan adjustments to the operation. In essence, enterprise budgets can help producers determine what to produce, how many acres to produce, the cost of production, and the necessary price to be profitable. In this document, we describe the process used to create the 2019/20 enterprise budget for tomatoes in southwest Florida.

Overview

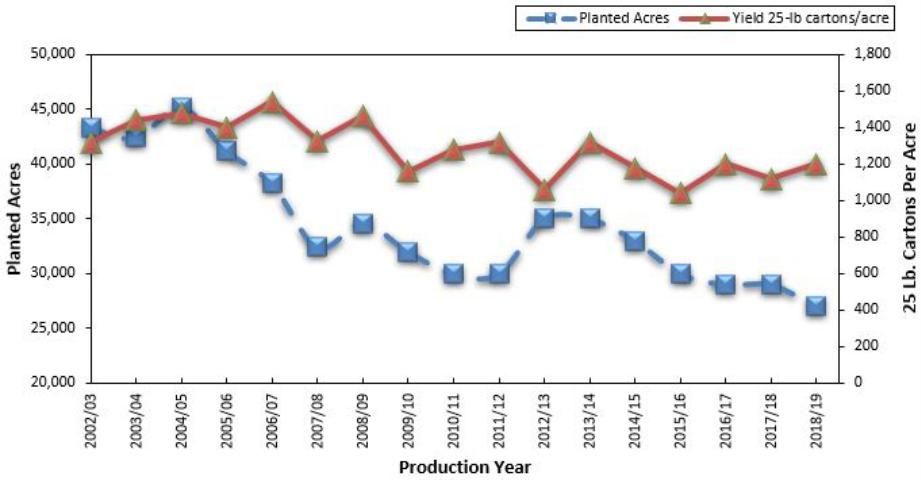

In 2017, Florida produced 39 percent of US fresh-market tomatoes, making Florida growers the top producer of this commodity in the United States. Florida harvested 26,000 acres of tomatoes during the 2018/19 growing season, valued at almost $426 million dollars (Table 1). Acreage planted to tomatoes in Florida decreased from a high of about 45,000 acres in the 2004/05 season to 30,000 acres in the 2010/11 season. It saw moderate rebounds in the next couple of seasons before it gradually dropped to 27,000 acres in 2018/19. Total value also peaked in 2004/05 at $804 million but has since declined to a low of $262 million in the 2016/17 season. Per-acre yield has been relatively steady over the past three years, but a record high price of $18.99 per carton resulted in a 27 percent increase in total value from 2017/18 to 2018/19. Yield per acre (25-pound cartons) averaged 1,343 cartons per acre from 2002/03 to 2013/14, but most noticeable is the decline since 2006/07 (Figure 1), thought to be due to methyl bromide being phased out of use at that time (Cao et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2019). Production peaked in 2004/05 at 62.1 million cartons but decreased to 31.2 million cartons in 2018/19, a 50 percent decrease. Value per carton ranged from a low of $7.00 in 2011/12 to a high of $18.99 in 2018/19.

Production Practices

Several production methods are used in producing Florida's tomato crop, with most being grown on polyethylene-mulched raised beds, supported with stakes, and irrigated with drip or seep irrigation. Portions of fertilizer can be applied at planting, during the plastic laying process, and during transplanting, with the rest applied throughout the season through the drip irrigation system.

Fumigants are used to help manage soil insects, pathogens, nematodes, and weeds, all of which are major pests in tomato production. Fumigants are injected into the soil during the raised bed construction and are immediately covered with plastic mulch. Most of Florida's tomato acreage applies 1,3-dichloropropene in combination with chloropicrin as a fumigant (Wu et al. 2019). Tomato transplants are planted in raised beds typically spaced 18 to 24 inches apart. Stakes, made from either wood or metal and approximately four feet long, are placed between the plants and driven into the beds for tying the plants. The plants are then tied with twine and pruned for support. Tomatoes are planted at intervals throughout the season to meet anticipated market demand and mature 90 to 110 days after transplanting.

The majority of Florida-grown round tomatoes are harvested at the mature-green stage. Depending on market conditions, growers may conduct 2 or more consecutive picks at 7- to 10-day intervals; however, under depressed market conditions growers may pick only once (crown pick). Round tomatoes are hand-picked into buckets and transferred into 1,000 lb bins or gondolas, which are transported to the packinghouse for sanitizing, sorting, grading, and packing. Before shipping, round tomatoes are held in ripening chambers and exposed to ethylene gas to ensure uniform ripening. Other varieties may be handled differently: Roma tomatoes are handled much the same way as round tomatoes but are typically placed in ripening rooms before grading, and grape and cherry tomatoes may be harvested multiple times. Growers typically target 45,000–50,000 lbs of tomato per acre, which translates into 1,700 cartons per acre or more depending on variety and market conditions.

Southwest Florida Tomato Budget

Table 2 is a per-acre enterprise budget for a representative grower in southwest Florida. The budget identifies specific cost components used to estimate the budget expense categories and total estimated production costs per acre. Production costs for the budget are reported in two categories, variable costs and fixed costs. Variable costs include labor wages, fuel, chemicals, seed, fertilizer, interest, and other costs that increase as land usage increases. Fixed costs can include rent, building ownership, depreciation, taxes, repairs and machinery. These are costs that do not vary with the level of output and result from ownership of assets. (It should be noted that there are two types of variable costs: cash and noncash. Cash costs, such as fuel, pesticides, repairs, etc., are included in the budget. Noncash costs, such as farmer and family labor, are not included in the budget. Though not included, we urge growers to consider noncash costs in their decision-making process.)

The budgets are intended to reflect the cost of production using representative production practices that are considered typical for tomatoes grown in southwest Florida. What constitutes a representative production practice is defined by a consensus of opinion of UF/IFAS field experts, industry experts, and 3 producers in the tomato production area. Cost estimates resulting from this process do not represent the average cost of production in a statistical sense, and production practices listed are not necessarily recommended production practices (see Freeman (2017) for a tomato production guide). The intent of this cost budget is to establish a benchmark within a comprehensive range of potential costs that could be expected to produce the crop.

Assuming an anticipated yield of 1,700 cartons per acre, the production budget for 2019/20 indicates that pre-harvest variable costs for a representative tomato grower in southwest Florida totaled $8,037 per acre. The top four expenses, which represented 49 percent of the pre-harvest variable costs, included fertilizer (10 percent), fungicide (11 percent), tractors and equipment (17 percent), and labor (11 percent). In addition, harvest and marketing costs totaled $6,035 per acre, of which 70 percent results from picking, packing, and hauling the tomatoes. The total cost of production is estimated to be $16,863.30 per acre or $9.92 per carton.

Methods

Production costs for the budget are reported in variable and fixed costs (Table 2). Similar to tomato budgets created in 2013/14 (VanSickle and McAvoy 2014), cost estimates are a combination of a consensus of opinion from industry experts, interviews with agriculture input retailers in the region, and applying an inflation factor to 2008/09 production costs. Two inflation factors were created to adjust the 2008 fixed and variable values of tractors and implements for those in 2018. The variable cost inflation factor is the average of the relative difference of 2008 and 2018 equipment prices. The machinery used in this estimate includes tractors and tractor implements from University of Georgia (2019), Clemson University (2017), University of Arkansas (2018), and Mississippi State University (2018) production budgets. The fixed cost inflation factor was calculated using the relative difference of the producer price index (PPI) for tomatoes in 2008 and 2018 (www.bls.gov/ppi). All other costs estimates are from three growers and five agriculture input retailers (e.g., seed and chemical companies) as well as other industry experts.

Resources

Interactive Budget Workbook

Interactive workbooks containing data used to create the UF/IFAS estimated tomato budget in Table 2 are available at https://fred.ifas.ufl.edu/extension/commodityenterprise-budgets/. These workbooks can be used to produce cost estimates broken down by specific groups. Included are pesticide, herbicide, insecticide, fungicide, and fumigant worksheets; machinery worksheets listing the machinery cost coefficients so that users can estimate fixed and variable costs of machinery; and a comparative budget designed to compare UF/IFAS estimates with grower estimates. The workbooks enable users to compare their production expenses to the estimates presented in Table 2. Users are encouraged to input their own prices and quantities. They may be saved to your computer and printed in their entirety or printed as individual worksheets.

Common Tomato Varieties for Commercial Production

- Large Fruited Varieties: BHN 602, BHN 730, BHN 975, Florida 47, Florida 91, HM 1823, Phoenix, Raceway, Red Defender, Red Rave, Sanibel, Sebring, SevenTY III, Soraya, and Tasti-Lee.

- Roma Varieties: BHN 685, Mariana, Monticello, Picus, Regidor, Sunoma, Supremo, and Tachi.

- Cherry Varieties: BHN 268, Camelia, Shiren, and Sweet Treats.

- Grape Varieties: Amai, BHN 785, BHN 1022, Cupid, Jolly Girl, Smarty, Sweet Hearts, and Tami G.

References

Cao, X., Z. Guan, G. E. Vallad, and F. Wu. 2019. "Economics of Fumigation in Tomato Production: The Impact of Methyl Bromide Phase-Out on the Florida Tomato Industry." International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 22 (1030-2019-2947): 589–600. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2018.0074.

Clemson University. 2017. Enterprise Budgets. Clemson University, Clemson Cooperative Extension. https://www.clemson.edu/extension/agribusiness/enterprise-budget/melons-vegetables.html. Last visited on 12/2/19.

Freeman, J., E. McAvoy, N. Boyd, R. Kinessary, M. Ozores-Hampton, H. Smith, J. Noling, and G. Vallad. 2017. Tomato Production. HS739. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Mississippi State University. 2018. Traditional Vegetables 2018 Planning Budgets. Mississippi State University, Extension. https://www.agecon.msstate.edu/whatwedo/budgets/docs/18/MSUVeg18.pdf. Last visited on 10/3/22.

University of Arkansas. 2018. 2018 Crop Enterprise Budgets for Arkansas Field Crops Planted in 2018. University of Arkansas, Division of Agriculture Research and Extension. https://www.uaex.uada.edu/farm-ranch/economics-marketing/farm-planning/budgets/2018%20Manuscript.pdf. Last visited on 10/3/22.

University of Georgia. 2019. Vegetable Production Guides, 2019 Tomatoes on Plastic – Fall Planting. University of Georgia, College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Extension. https://agecon.uga.edu/extension/budgets.html. Last visited on 12/2/19.

VanSickle, J., and E. McAvoy. 2014. Production Budget for Tomatoes Grown in Southwest Florida and in the Palmetto-Ruskin Area of Florida. Food and Resource Economics Department. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://fred.ifas.ufl.edu/extension/commodityenterprise-budgets/

VanSickle, J., S. Smith, and E. McAvoy. 2009. Production Budget for Tomatoes in Southwest Florida. FE818. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00003786/00001

Wu, F., B. Qushim, Z. Guan, N. S. Boyd, G. E. Vallad, A. MacRae, and T. Jacoby. 2019. "Weather Uncertainty and Efficacy of Fumigation in Tomato Production." Sustainability 12 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010199