Edible ornamental landscaping is the “artful combination of edibles and traditional ornamentals in the garden” (Hansen 2019). Well-designed edible ornamental landscapes, also called foodscapes, provide landowners with aesthetically pleasing, multipurpose gardens that provide food, color, and cover year-round. Not only can these landscapes provide a source of healthy, locally grown food in urbanized communities, but they can also promote energy and water conservation, improve food security, and provide wildlife habitat (Çelik 2017). By converting conventional yards into sustainable, edible ornamental landscapes that utilize the principles of Florida-Friendly Landscaping™, we may quell some of the health and environmental impacts of rising population growth and urbanization (Çelik 2017).

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

The purpose of this publication is to guide Floridians on how to design, install, and maintain their edible ornamental landscape using reliable plants suitable for north-central Florida and the best management practices of Florida-Friendly Landscaping™.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ with Edibles

The Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ (FFL) program is a statewide initiative to promote attractive, low-maintenance landscapes that conserve water, protect water quality, and provide wildlife habitat. The nine principles of FFL can be applied to any landscape, including edible ornamental landscapes, to reduce maintenance costs, irrigation, and the need for chemical pesticides and fertilizers (see EDIS publication ENH1330, “Edible Landscaping Using the Nine Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principles”).

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Right Plant, Right Place

The first and foremost principle of Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ is to select plants best suited for the site conditions. Your edible ornamental landscape can be attractive and productive, all while conserving water and protecting water quality by selecting the right plants for the climate, light, space, soil, and water conditions of your yard. These plants can be native or non-native but should not be listed as invasive exotic (see guidance from the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants). By using the right plant, right place principle, you can prevent many issues from the very beginning to reduce your landscape maintenance needs.

Temperature and Lighting

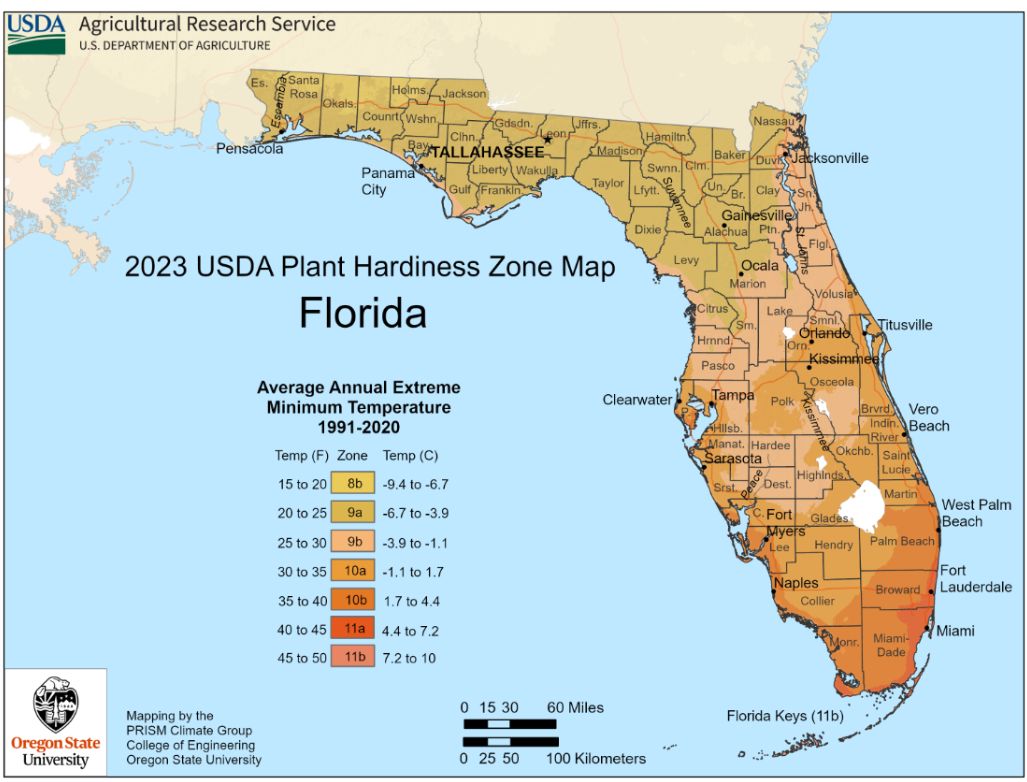

To select the right plants, you will first need to know in which plant hardiness zone you reside. Average winter minimum temperatures, which dictate USDA plant hardiness zones, vary widely in Florida. North-central Florida primarily includes zones 9a–9b, which have an average minimum winter temperature of 20°F–30°F. Temperatures along the coast tend to be milder. Selecting plants that are hardy in your zone will reduce the care they will need to thrive through the seasons.

Credit: U.S. Department of Agriculture

Likewise, some edible plants, such as peaches, plums, and blueberries, require a certain number of chill hours to be productive (see the AgroClimate chill hours calculator). These crops will need a minimum number of accumulated hours during winter between 32°F and 45°F to set fruit consistently. To promote optimal productivity, select low-chill cultivars for your north-central Florida edible ornamental landscape (see EDIS publication FC23, “Dooryard Fruit Varieties”). Some fruit trees, such as apples, peaches, plums, and nectarines, may not be reliable producers given the variable winters in this region. Plants may accumulate more chill hours if planted on the north side of a structure or in a location with early-morning shade. Plants that are less cold hardy should be planted on the south or southwest side near pavement or large trees.

Once your list of plants has been narrowed to those that are hardy and productive in your climate zone, observe the sunlight conditions of your landscape. Most edible plants will need partial-to-full sun, but some, like edible ginger and turmeric, thrive in shade. Keep in mind that light conditions may change as plants mature, leading us to the next consideration for selecting the right plants for your edible ornamental landscape: spacing.

Spacing and Soil

Overcrowding is a common issue in the landscape. Plants that are too close together or too close to structures, such as buildings and lanais, become stressed, less productive, and more susceptible to pests and disease. Plants that become too large for a given space are often pruned to maintain a desirable size, but over time, this can lead to branch dieback and general decline. Familiar examples of poor plant spacing are trees planted under power lines and large shrubs planted in front of windows. Know the mature size of a plant before you plant it, and keep in mind that many plant species have been cultivated into a variety of different sizes.

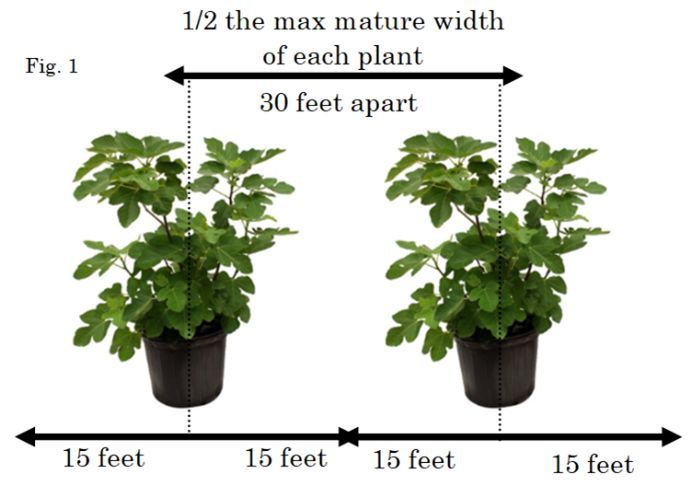

To properly space a plant, measure from the center of the plant to the center of the next. For example, a plant that reaches 30′ wide at full maturity should be planted 30′ away from the next plant, measured from the center stem or trunk. As a rule of thumb, small-to-medium-sized trees should be planted at least 15′ away from the foundation of any structure. Bushes and other plantings should be planted forward of the roof dripline, leaving at least 2.5′ of space between the plant at mature size and the foundation. Keep trees and shrubs far from septic tanks, drainage fields, and wells to avoid expensive plumbing issues in the future.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Before investing in new plants, be sure to get a soil test. Research the preferred soil pH and moisture level of the plants you want to install, selecting plants that best match your soil pH, moisture, and drainage conditions. Sandy soils tend to be dry and well-drained, while clay holds moisture and drains poorly. Most plants prefer soils to have an acidic pH between 5.5 and 6.5. It is relatively easy to raise soil pH but nearly impossible to permanently lower it significantly. Therefore, it is best to match the plants to the soil rather than try to fix the soil conditions to match the plants. Contact your county UF/IFAS Extension office for more information and assistance on testing your soil pH and nutrient content.

Design Considerations and Establishment

The design of your edible ornamental landscape should be easy to maintain once established and attractive to you and to wildlife year-round. If you live in a homeowners association or deed-restricted community, be sure to get approval prior to making any changes to your existing landscape. An edible ornamental landscape can follow much of the same general design considerations as a traditional landscape, with additional consideration for seasonality. Select a diversity of plants that produce blooms or fruit in different seasons for year-long color and fruit production. It is also recommended to intermix evergreen plants or winter annuals with deciduous plants to avoid excessive brown, bare areas during the winter dormancy months. As with any landscape, select pest- and disease-resistant varieties or cultivars to minimize the need for pesticides.

A plant is considered established when it can survive without irrigation (see EDIS publication ENH1114, “Frequently Asked Questions about Landscape Irrigation for Florida-Friendly Landscaping Ordinances”). Florida-friendly plants selected according to site conditions and planted correctly typically require little to no irrigation once established. However, it is imperative that all new plants receive regular irrigation until that time. The larger the plant is, the longer it will take to establish. Fruit-bearing trees and shrubs may need supplemental irrigation during fruit set if rainfall is not adequate. When irrigation is necessary, such as during establishment and fruit set, microirrigation that delivers water efficiently to the roots is recommended. Not only does microirrigation conserve water, but it can also reduce disease pressure by keeping the leaves dry. Once the plants are established, microirrigation systems can be removed easily and used elsewhere. A 2″–3″ layer of organic mulch can likewise help hold moisture and allow plants to establish more easily. Pine straw and pine bark mulch are the best at weed suppression and help acidify the soil as it decomposes, adding organic matter to the soil. Keep mulch at least a few inches away from the base of all plants and 10″ or more from the trunks of trees to maintain root health. A light 1″ layer of mulch over the root ball for aesthetics is acceptable.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Pollinators and Pesticides

To protect yourself and pollinators, it is important to always read and follow label instructions for pesticides, particularly when applying to edibles and plants in bloom. Flowering plants provide nectar and pollen for honeybees and native pollinators. Some plants, such as passion fruit, are hosts for moths and butterflies. Adults lay eggs on the host plant; larvae then eat the leaves, typically causing no permanent damage, until they pupate and fly away to start a new generation. By adding pollinator plants to your edible landscape, your plants will bear more fruit, pest and disease pressure will be reduced, and you will provide critical habitat for struggling pollinators.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Before treating, identify the insect first. Less than 1% of all insect species in the world are plant pests, meaning the vast majority are beneficial or benign. If treatment is necessary, utilize mechanical removal, such as pruning off damaged branches or picking off infested leaves, before moving on to the least toxic chemicals first. For many sap-sucking insect pests, such as aphids and scale, neem oils and horticultural soaps are effective while posing minimal risk to our beneficial insects. Positively identified caterpillar pests can also be benignly treated with a Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) product that is nontoxic to bees and will kill the caterpillars once ingested. Regardless of how safe, natural, or even organic a product is labeled, the application and safety instructions should always be followed. Pay particular attention to product application on edibles and the preharvest interval (PHI) (how long to wait after treatment before harvesting). Utilize your UF/IFAS Extension office for pest identification assistance and integrated pest management recommendations (see EDIS publication ENY-350, “Natural Products for Managing Landscape and Garden Pests in Florida”).

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Edible Ornamental Plants for North-Central Florida

Once the conditions of your site have been analyzed and you have drafted a landscape design and maintenance plan, it is time to select your edible ornamental plants. The plants selected for your landscape should be Florida-friendly and should meet your needs and wants in terms of both aesthetics and productivity. There are countless options; however, for the purposes of this publication, the following perennial plants have been highlighted for their ease of maintenance, reliable health and productivity, and overall aesthetic appeal for north-central Florida edible ornamental landscapes. Please see Tables 1–4 for a summary of these and other recommended plants to consider. Contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office for recommendations for your specific area.

Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.)

Credit: M. Bailey, UF/IFAS

There are several native species of blueberries in Florida: shiny (V. myrsinites), Darrow’s (V. darrowii), Elliott’s (V. elliottii), rabbiteye (V. virgatum), and highbush (V. corymbosum). Depending upon the species, blueberry plants can range in size, shape, and color. Typically, most blueberry plants are small to medium-sized shrubs. Blueberry is naturally shallow-rooted and needs well-drained, acidic soil. Blueberry should be planted with the top of the root ball slightly above the soil line. Pine bark and pine needles have soil-acidifying properties and are good choices for weed suppression under blueberry plants. Blueberry also has a chilling requirement to effectively produce flowers and leaf out during spring. To help facilitate chilling requirements, choose a location that is exposed to cold northern air or has early-morning shade, allowing the plant to stay cooler longer in the morning. Blueberry is more productive when frequently fertilized with a light 12-4-8 formulation. Blueberry plants usually need one or two years before they begin to produce fruit. More information about blueberry production can be found in EDIS publication CIR1192, “Blueberry Gardener's Guide.” The time of year blueberry flowers and sets fruit greatly depends upon the species. Southern highbush varieties are typically the first to flower and set fruit from late winter into early spring, while rabbiteye bushes will have ripe fruit available in early summer. You will need to plant at least two different cultivars of the same type to achieve cross-pollination and, therefore, fruit production. Shiny and Darrow’s blueberries are small plants and produce small fruits that are typically ready to harvest in late spring. All native Florida blueberry species produce edible berries that can be utilized in many ways—fresh, dried, juiced, or preserved.

Landscaping with Blueberry

Rabbiteye and southern highbush blueberries can be used as deciduous edible hedges in the landscape. Rabbiteye varieties of blueberry can reach 12′–15′ high and 8′–10′ wide, so plant these in areas that allow for ample space at maturity without overcrowding. If creating a hedge, plant them about 7′ apart center-to-center. Southern highbush tends to stay smaller than rabbiteye and can be planted in rows about 5′ apart, but it may still be too large for some home landscapes. In those instances, the shiny or Darrow’s blueberry bushes may be better choices. These little evergreen bushes stay about 2′ tall and wide, and in addition to the small but tasty berries, the purple-colored foliage is highly attractive in the landscape. Plant blueberry bushes in full sun for optimal health and fruit set.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Ginger and Turmeric (Zingiber officinale and Curcuma longa)

Credit: M. Bailey and A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Most edible ginger plants originated from Asia, where they have been cultivated for thousands of years. A wide range of species belong to the ginger family (Zingiberaceae). Some of the species within the ginger family include edible gingers, turmeric, and cardamom. These plants are grown from underground rhizomes, which are modified plant stems. Ginger plants are well-adapted for partial shade and will need to be planted in good-quality soil for the plant to thrive. Generally, after a full growing season, ginger plants can be harvested, or they can remain in the soil and continue to grow. Ginger plants can be propagated after harvest by using sections of the harvested rhizome. Rhizomes can be used fresh in dishes, dried as a ground spice, candied, or used in beverages.

Landscaping with Ginger and Turmeric

Both ginger and turmeric are shade-loving plants and can therefore be incorporated into your edible ornamental landscape where many other plants will not thrive. These plants are deciduous but will return from the clumping underground rhizomes in the spring. Consider adding nonedible ornamental gingers such as butterfly ginger, which grows to about 4′ tall and has attractive, sweet-smelling, white blooms, to the shadier parts of your landscape or the low peacock ginger as a groundcover under the shade of your loquats and other shade trees. Pinecone gingers, also called shampoo gingers, grow to about 6′ tall and get a vibrant red cone-like flower stalk with cream-colored flowers that are attractive to pollinators. When the red cone is squeezed, a sweet, fresh-smelling liquid can be collected and used to make soaps and shampoos (hence the name). The family of gingers is quite large, and landscapers can add great color and diversity in the shadier areas of their yards by incorporating both the edible and nonedible varieties.

Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus)

Lemongrass is a large, perennial, clumping grass that originated from India. It is best to plant lemongrass in spring or summer, allowing it to become fully established before dangerous winter freezes occur. Once established, this plant requires minimal inputs. It can be harvested by cutting off the leaf stems or stalks from ground level to a height of about 2′. Lemongrass has a strong lemon fragrance and can be used to flavor soups, dishes, or beverages.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Landscaping with Lemongrass

Florida-friendly ornamental grasses can easily fill in large areas of a landscape and add diverse textures, heights, and colors. In the case of lemongrass, it can add scents and flavors as well. Consider planting lemongrass individually to showcase its cascading leaves, en masse, or as a large border plant in full-to-partial sun where you can enjoy the lemony scent. Lemongrass can serve as a living privacy fence, growing to approximately 6′ tall and 4′ wide, by planting them about 4′ apart, center-to-center, to allow proper airflow. The seed heads of lemongrass that emerge in late fall to early winter may grow an additional 3′ tall. Lemongrass is undesirable to deer and may help deter them from areas of your landscape. This perennial grass will stay green most of the year but will turn brown after a hard freeze. Cut out any dead or damaged leaves toward the end of March, after the chance for freeze has typically passed.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica)

Credit: M. Bailey and A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Loquat originates from East Asia and is one of the best-adapted fruit trees for north-central Florida. It is very cold hardy and can endure long periods of drought. It also requires minimal inputs or pruning to be highly productive. This tree thrives in both full sun and partial shade in well-drained locations. There are improved loquat varieties, though unimproved seedlings are far more readily available. Loquat is somewhat unusual by flowering in winter, with fruit becoming ripe in late winter and early spring. Fruit can be picked once they turn a golden or orange color. The skin of the fruit, depending upon variety, may have fuzz that can be removed, and the flesh is very sweet, juicy, and slightly acidic. Each fruit will contain one or several seeds that can be easily removed. Plants usually need to grow for three or more years before becoming productive. This tree is an excellent choice for an edible ornamental plant that requires minimal inputs for high quality and quantity of fruit. More information about loquat production can be found in EDIS publication HS5, “Loquat Growing in the Florida Home Landscape.”

Landscaping with Loquat

Loquat (sometimes sold as Japanese plum) serves as a lovely evergreen shade tree in the landscape, growing to about 30′ tall. Multiple loquats in a landscape can quickly shade a large area. Oftentimes, however, one specimen loquat in the yard provides an ample amount of shade and fruit. The leaves, much like magnolias, are thick and waxy and therefore decompose slowly, which may be a nuisance to some homeowners. Blow or sweep off fallen leaves from patios and walkways and utilize the leaves as free mulch or add to compost piles. Organic mulches, such as pine bark, pine straw, or melaleuca, can be put down under the shade of a loquat; alternatively, consider planting shade-tolerant plants, such as ferns, caladiums, Persian shield, coontie, Xanadu philodendrons, bromeliads, or edible gingers and turmeric.

Mulberry (Morus spp.)

Mulberry is native to Florida as well as Europe and Asia. Commonly available species include red (native), black, and dwarf everbearing mulberries. Mulberry grows rapidly and is well-adapted to the extremes of Florida weather. Mulberries are relatives of the fig and have similar requirements. It is best to plant mulberry in full sun and well-drained soil. Once established, it does not require fertilizer, although excessive growth may need to be managed with aggressive pruning. Like the fig, mulberry cuttings can be used for propagation. Mulberry typically begins to produce fruit during the early spring and intermittently throughout the year, depending upon variety and other factors. Most mulberries produce fruit that begin green, turn pink or red, and finally darken to a purple black once fully ripe. Ripe fruit are tender, flavorful, very sweet, and juicy. Ripe mulberries can be eaten raw, juiced, dried, or turned into jam.

Credit: M. Bailey, UF/IFAS

Landscaping with Mulberry

Mulberries vary widely in size depending on cultivar. The native red mulberry (Morus rubra) and non-native black mulberry (Morus nigra) can both grow to be medium-sized trees up to 40′ tall. The white mulberry (Morus alba) can grow even taller, up to 60′. Take extra care to ensure these trees are planted far enough away from wells, drainage fields, and foundations. For smaller landscapes, the dwarf everbearing mulberry may be the best alternative, only growing to 15′ tall. Homeowners can also choose to prune their mulberry trees into bushes to keep the size down and to make harvesting the fruit easier. Mulberry is deciduous and will therefore lose its leaves in winter but is a great specimen shade tree in the landscape for most of the year. The dark-colored fruits can stain pavement when they fall. If that is a concern, be sure to plant your mulberry far enough away or choose light-colored fruit cultivars, such as ‘King White Pakistan’ or ‘Tehama’. Mulberry fruit is also highly attractive to wildlife, which may be a concern in some communities, particularly areas prone to bears. If you live in a homeowners association, always get HOA approval before adding new plants, particularly edibles, to your landscape.

Muscadine Grape (Vitis rotundifolia)

Credit: M. Bailey, UF/IFAS

The muscadine grape is native to Florida and widespread across the Southeast. It is a long-lived climbing vine that produces clusters of grapes and can grow to great lengths. In the wild, muscadine grapes are dioecious, which means they are divided into male and female plants. Most are male, which serve to pollinate fruit-bearing female plants. They grow best in moderately acidic (pH 5.5–6.5) soil that is rich and well-drained. They are well adapted for conditions in the Southeast and are notably more disease resistant when compared to the European grape (Vitis vinifera). Muscadine grapes are most productive when provided full sun, adequate water, and seasonal pruning in mid-to-late winter. The addition of fertilizer can help increase yield and fruit quality after budbreak. Muscadine grapes come in a wide range of sizes, colors, textures, and flavors. Many varieties exist with characteristics that include disease resistance, vine vigor, fruit quality, and overall yield. Some varieties are self-fertilizing, while others will need to be planted with compatible varieties that will pollinate one another. Fruit typically take about 100 to 120 days to mature and can be eaten raw as soon as they are ripe. Most varieties contain seeds, though some new varieties are “seedless.” In addition to being eaten raw, they can be juiced and turned into beverages or jellies. For more information, please see EDIS publication HS763, “The Muscadine Grape (Vitis rotundifolia Michx.).”

Landscaping with Muscadine Grapes

Muscadine grape is a deciduous vine; therefore, the trellis it grows on will be largely bare and exposed in the winter months. Consider using a strong but decorative trellis for this reason or simply use a sturdy fence to have a native, living border along your property line. Muscadines can become quite aggressive and can reach their tendrils onto nearby plants or structures, so be sure to keep about 5′ of clear space around the vines. By having ample air space, the muscadines will also have better sunlight exposure and airflow to improve yield and reduce pest or disease pressure. Muscadines do not produce as well when there is competition around their roots. Avoid planting other plants around the root zone and try to keep the area clear of weeds and grass by using a 3″ layer of organic mulch and edging material of your choosing.

Persimmon (Diospyros spp.)

Credit: M. Bailey, UF/IFAS

Japanese persimmon (Diospyros kaki) are native to East Asia. They are a small-to-medium-sized deciduous trees, typically growing 10′–20′ tall and wide with a single trunk and producing yellow-orange fruit, although the size of both the trees and fruit, as well as fruit color, vary widely depending on the cultivar. Persimmon grows best in full sun with well-drained soil and infrequent irrigation. Fertilizer is not necessary for this tree to grow effectively in most soils. A young tree may require two or more years before it will produce fruit. As the weather cools, persimmon trees will drop their soft leaves, but the brightly colored yellow-orange fruit may remain throughout much of the winter. There are several varieties of Asian persimmon that have characteristics such as astringent and non-astringent and differences in flavor, texture, and appearance. Fruit should be picked or cut from the tree once fully ripe. Fruit may remain on the tree long after the leaves have dropped and are fully ripe after a slight softening of the fruit. The ripe fruit can be eaten raw and will have an increasingly soft texture depending on how ripe the fruit is. The fruit can also be readily dried, used for jellies, and used in baking persimmon cookies and bread. For more information, visit EDIS publication SP101, “Japanese Persimmon Cultivars in Florida.”

Landscaping with Persimmon

Japanese persimmon is an attractive, small tree for your edible ornamental landscape, particularly in the fall and early winter when orange fruit adorn the branches. It will be bare in the late winter months, however, so consider planting evergreens or winter annuals around it for year-round color. Despite its small size, be sure to keep it at least 15′ from building foundations. Be aware that the fruit will attract wildlife and may make a mess if not harvested. The native common persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) is also deciduous but is a much larger tree, growing up to 60′ tall and 35′ wide. It produces smaller, more astringent fruit and is not as commonly planted in landscapes. The common persimmon is suitable for larger, more naturalized yards.

Pineapple Guava (Acca sellowiana)

Pineapple guava is a perennial plant native to South America that produces attractive edible flowers and fruit. It is tolerant of both high temperatures as well as mild freezing temperatures. Pineapple guava benefits from some chill hour accumulation. It is well adapted to most conditions in Florida and grows best in well-drained soil. It flowers in spring, and its fruit ripen toward the end of summer. The fruit turn slightly more yellow green and start to drop off when ripe. The flesh is best eaten raw and has a mild, sweet, guava-like flavor. There are named cultivars, although many nurseries simply sell them as pineapple guava. Fruit production tends to be best when more than one is planted. See EDIS publication HS1424, “Growing Feijoa Fruit in Florida” for more information.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Landscaping with Pineapple Guava

For an evergreen, attractive hedge or small tree in your landscape, consider pineapple guava (also called feijoa). Its dark-green leaves with silvery undersides add beautiful color and texture. The edible red and white blooms are quite lovely and unique and are followed by gray-green, oval-shaped fruit. Pineapple guava is an excellent edible alternative to the bottlebrush tree or crape myrtle that are more commonly planted. Consider planting pineapple guava as single- or multitrunked trees in the landscape or as a pruned hedge. Left unpruned, this plant can grow 10′–15′ tall and wide but tolerate hedging well at about 4′–5′. Pruning is best done after fruiting. Dwarf cultivars that have smaller leaves and flowers and naturally grow only 3′–4′ tall and wide, such as ‘Bambina’, may be more suitable for smaller spaces.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and Other Herbs

Rosemary is a fragrant evergreen shrub that originates from the Mediterranean region. It is extremely drought tolerant and well adapted for high heat. Rosemary is somewhat slow-growing and is most productive when planted in full sun with well-drained soil. Rosemary, like many herbs, will not tolerate soggy soils for long. The small leaves produce a fragrant scent, especially when touched or crushed. The leaves are edible and can be used as a spice for a range of foods, such as meat and bread. The leaves of rosemary and many other herbs can be used fresh or dried for long-term storage.

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Landscaping with Rosemary and Other Herbs

Rosemary and other herbs can add great diversity, textures, and scents to your edible ornamental landscape. The blooms are likewise highly attractive to many pollinators. Rosemary can grow 4′–6′ tall and wide depending on the variety, so be sure to give it ample space. Consider adding a mix of annual and perennial herbs such as rosemary, African blue basil, holy basil, onion chives, and more to fill in the smaller, sunnier areas of your edible ornamental landscape (see Table 1). You can also support pollinators in your garden by incorporating host plants that black swallowtail caterpillars will consume, such as fennel and parsley.

Yaupon Holly (Ilex vomitoria)

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Yaupon holly is a native plant available in many different shapes and sizes as a tree or shrub. It is well adapted for a wide range of conditions throughout north-central Florida. Yaupon holly is a rather unique edible ornamental plant for having naturally caffeinated leaves rich in antioxidants that have been used for centuries by Native American cultures. The leaves may be dried and steeped to produce a caffeinated tea. Yaupon holly tea production is a growing industry in Florida.

Landscaping with Yaupon Holly

Yaupon holly is readily available in a wide diversity of cultivars, making it an excellent evergreen staple in the edible ornamental landscape. For smaller spaces or for a foundation hedge, consider a dwarf cultivar such as ‘Nana’, ‘Schillings Dwarf’, or ‘Bordeaux’. For a specimen tree, consider the ‘Pendula’ weeping yaupon holly or the original standard. In the winter months, female trees produce festive red berries, which birds love; if you want these berries, be sure to purchase a female tree because males do not produce them. Also, keep in mind that some of the hybrid dwarf cultivars, like ‘Schillings’, do not produce berries, although these bushes more than make up for it with their low-maintenance, attractive, naturally rounded form. In the spring, both male and female plants will produce small white flowers that are attractive to pollinators. Yaupon hollies are highly drought tolerant and hardy; they do well in many different site conditions, from wet to dry, acidic to alkaline, and full sun to full shade. This is truly one of the most undemanding edible ornamental plants to consider for your landscape.

For more information, see EDIS publication ENH470, “Ilex vomitoria: Yaupon Holly.”

Other Edible Ornamentals

In addition to the plants listed above, there are countless other edible ornamental plants to consider for your landscape. Contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office for recommendations and information on these and other Florida-friendly edible plants for your yard (see Tables 1–4):

- African blue basil

- Amazel Basil®

- Beautyberry

- Calendula

- Chives: Onion and garlic

- Holy basil

- Nasturtium

- Pawpaw

- Pindo palms

- Pineapple sage

- Society garlic

Credit: A. Marek, UF/IFAS

Table 1. Edible Ornamental Plants for North-Central Florida—vines.

*Heights and widths indicated are typical averages for north-central Florida. Actual sizes of mature plants may vary considerably depending on site conditions, cultivars, maintenance given, and so forth.

Table 2. Edible Ornamental Plants for North-Central Florida—herbs and flowers.

*Heights and widths indicated are typical averages for north-central Florida. Actual sizes of mature plants may vary considerably depending on site conditions, cultivars, maintenance given, and so forth.

Table 3. Edible Ornamental Plants for North-Central Florida—grasses and shrubs.

*Heights and widths indicated are typical averages for north-central Florida. Actual sizes of mature plants may vary considerably depending on site conditions, cultivars, maintenance given, and so forth.

Table 4. Edible Ornamental Plants for North-Central Florida—trees.

*Heights and widths indicated are typical averages for north-central Florida. Actual sizes of mature plants may vary considerably depending on site conditions, cultivars, maintenance given, and so forth.

References

Ҫelik, F. 2017. “The Importance of Edible Landscape in Cities.” Turkish Journal of Agriculture—Food Science and Technology 5 (2): 118–124. https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v5i2.118-124.957

Dukes, M. D., B. Cardenas, L. E. Trenholm, et al. 2024. “Frequently Asked Questions about Landscape Irrigation for Florida-Friendly Landscaping Ordinances: ENH1114/WQ142, rev. 9/2024.” EDIS 2024 (6). https://journals.flvc.org/edis/article/view/136564

Hansen, G. 2019. “Landscape Design with Edibles: ENH1214/EP475, 5/2013.” EDIS 2013 (5). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ep475-2013