Introduction

The tea scale, Fiorinia theae Green, is a small insect (1.5mm) indigenous to Asia and a pest of numerous plant species throughout the warmer regions of the world. E. E. Green published the first description of F. theae in 1900 based on females he collected in India on tea plants. The demand for ornamental camellias is thought to have led to the introduction of tea scale into the United States and as early as 1908 it was already a pest on camellias in South Carolina.

Distribution

In the United States, tea scale has been found in several southeastern localities on camellias and hollies including; Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Louisiana. Tea scale has also been spread to the western states of Texas and California. The range of tea scale is not limited to the United States. It is known throughout the world as a pest of numerous plants. It has been reported on tea, olive, and citrus plants in India as well as on Eurya japonica in Japan and Camellia japonica in Argentina.

Life Cycle

The length and developmental rate of the tea scale depends upon the climate in which it resides. In Florida for example, F. theae remains active throughout the year, but in the colder climates of Georgia and the Carolinas its activity is slowed, which results in fewer generations per year.

Between temperatures of 86°F to 91°F adult female tea scale begin a four to six day incubation period before laying eggs. Eggs are arranged in two rows under the scale armor. The first-instar nymph of tea scale is the motile "crawler" phase, which hatches within 10 days. The crawler stage represents the only stage in which infestation is actively spread. They emerge from under the armor of the adult female and move about the plant for one to four days seeking succulent plant tissues into which their piercing-sucking stylets are inserted. After inserting their stylets, the crawlers will remain stationary and molt about 10 days later. Sex can be determined after this first molt. Males are initially yellow but secrete a thin soft white armor. Male tea scales will molt three more times prior to reaching sexual maturity during which time they will develop one pair of wings, one pair of halteres, and nonfunctional mouthparts. The adult male's only purpose is to follow pheromones, and copulate with the adult mating female. Females, on the other hand, require only two molts before reaching sexual maturity. The second molt takes place about six days after the first. The female will retain the skin from the first molt, which will become sclerotized in time and give the adult female its characteristic brown color.

Credit: University of Florida

In severe infestations, crawlers, immature males and females will cluster together resulting in a fuzzy appearance. Depending on temperature, the tea scale life cycle takes between 45 to 65 days. An adult female will lay between 10 to 15 eggs, shrivel up, and die shortly thereafter. In warmer climates like Florida, scales reproduce continually throughout the year but in cooler climates hatching will often coincide with the warming spring temperatures.

Description

Eggs

Eggs are shiny yellow, oval in shape, and are broader at one end than the other. Shortly before hatching, the egg will appear dull yellow.

Crawlers

Crawlers are flat, oval, and yellow with six well-developed legs and two antennae.

Adult Female

Adult females will appear light yellow becuase of the retained skin from the first molt. Then the skin will harden and turn brown producing a narrow and elongate armor possessing an even darker distinct median longitudinal ridge. The adult female will remain yellow but hidden from view by her protective covering.

Adult Male

The adult male is described as being orange-yellow in color with one pair of glossy forewings with reduced venation and a pair of halteres representing the hindwings. As adults, males are without functional mouthparts and follow pheromones to waiting females.

Economic Significance

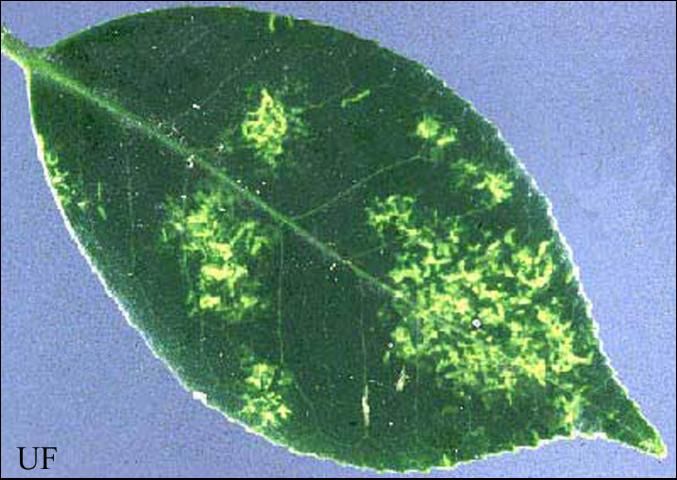

In Florida, tea scale is a pest of camellias and numerous species of holly. It is also considered a pest of tea, citrus, dogwood, bottlebrush, kumquat, mango, and olive here and elsewhere in the world. In 1995, scales in general were the targets of 12% of insecticide sprays in Florida. Their piercing mouthparts drain the plant of nutrients causing a yellow stippling (chlorosis) of the leaf's upper surface. They are difficult to control partly because they primarily infest the underside of the leaf making spray coverage difficult, as well as their continuous reproduction in warm climates, and because they are protected by a waxy covering. Frequently, dead scales and damaged leaves remain on the plant making the product aesthetically unappealing to consumers. Dead scales exude no body fluids when squeezed between the thumb and forefinger.

Credit: University of Florida

Credit: University of Florida

Management

Cultural

For camellias, pruning is an effective way to provide for better coverage of chemical sprays and increase air circulation. In cooler climates small non-flowering branches growing on major limbs within the interior of the plant should be pruned between February and March.

Chemical

In cooler climates, spring is the best time to apply chemical insecticides as the danger of cold weather has passed and egg hatching often coincides with the warming temperatures. It is essential that through coverage of the leaf's under-side is attained. The addition of a sticker-spreader is an effective way to increase coverage. Repeat applications (2-3) made between seven to 10 days apart is necessary to manage a tea scale infestation. Prior to making pesticide applications, efforts should be made to insure that a current tea scale infestation is not being naturally managed by native parasites. The use of soaps and oils are preferable to insecticides because they are usually less harmful to the natural predators of tea scale. Follow the manufacturer's labeled rate for any product applied to control a pest.

Biological

Several wasps native to the United States, including Aphytis diaspidis and two species of Aspidiotiphagus, have been reported parasitizing tea scales in Florida and Georgia. The female wasp will insert a single egg into the tea scale. Parasitized scales have detectable holes chewed out in their armor by the emerging wasp and are often associated with patches of necrotic tissue.

Selected References

Cooper RM, Oetting RD. 1987. Hymenopterous parasitoids of tea scale and camellia scale in Georgia. Journal of Entomological Science. 22: 297-301.

Cooper RM, Oetting RD. 1988. Biological control of tea scale and camellia scale. The American Camellia Yearbook. 43-46.

Munir B, Sailer RI. 1985. Population dynamics of the tea scale, Fiorinia theae (Homoptera: Diaspididae), with biology and life tables. Environmental Entomology 14: 742-748.

Green EE. 1900. Remarks on Indian scale insects (Coccoidae) with descriptions of new species. Indian Museum Notes 5: 3-4.

Das GM, Das SC. 1962. On the biology of Fiorinia theae Green (Coccoidea: Diaspididae) occurring on tea in northeast India. Indian Journal of Entomology 24: 27-35.

Hesselein CP, Chamberlin JR, Williams ML. (August 1999). Control of tea scale on 'pink snow' camellia using root-absorbing systemic insecticides. 1999 Ornamentals Research Report. http://www.aaes.auburn.edu/comm/pubs/researchreports/ornamentals99/control/teascale.html (19 November 2001).

Kuitert LC, Dekle GW. (1972). Tea Scale, Fiorinia theae Green (Homoptera: Diaspididae). Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Entomology Circular 120.

Midcap JT. et. al. (August 1999). Camellia Culture for Home Gardeners. Georgia Extension Service Publications. http://www.caes.uga.edu/publications/pubDetail.cfm?pk_id=6015 (19 November 2001).