Introduction

There are nearly 5,000 registered beekeepers in the state of Florida (as of December 2022). Nearly 85% of these are considered "backyard" beekeepers (0–40 colonies), while the remaining 15% are "sideline" (41–100 colonies) or "commercial" beekeepers (100+ colonies). In total there are over 650,000 managed colonies in the state that produced 8 million pounds of honey in 2021 (USDA 2022). The average winter colony loss in Florida as reported by the Bee Informed Partnership Management Survey was around 24% between 2014 and 2015. This is the third lowest rate across the nation with only Hawaii and Texas reporting lower colony losses in that time period (BIP 2016). This EDIS document gives an overview of what makes Florida a unique state in which to keep honey bees.

General Characteristics of Florida

Florida is characterized by long, hot and humid summers and mild winters. Unlike in northern climates, honey bees are able to fly, and queens are able to lay eggs almost any time of year. As a result, many of the commercial beekeepers in the United States move their bees to Florida during winter to take advantage of the state's favorable climate.

Although no part of Florida lies strictly in the tropics, much of the state is characterized by distinct tropical wet and dry seasons corresponding to high and low sun periods respectively. Florida can roughly be divided into two areas, a north and western (panhandle) section and a southern peninsula. In north Florida, minor rainfall peaks also occur in the spring and winter. Rainfall is generally sporadic, generally in the form of localized thundershowers.

There is about a six degree latitude difference between the extreme north of the state and its southern tip, which accounts for about an hour and a half photoperiod (day length) difference. The long length of days in Florida is advantageous for beekeeping. The sun shines longer in the winter and shorter in the summer than in more temperate regions. The state also spans several climatic zones, and temperate, subtropical, and true tropical conditions are present in different parts of Florida. The state's proximity to the ocean moderates extremes in temperature throughout the year.

Hazards

Unfortunately for beekeepers, the very conditions that make Florida a great place to keep bees also make it a great place for bee pests and diseases to do well. The warm climate allows colonies to maintain brood throughout much of the year. While this is a good thing for overall colony growth, it also leads to higher Varroa populations throughout the year, as this is a pest that reproduces in the brood of the honey bee colony. Some pests, such as small hive beetles, thrive in climates like Florida's due to the higher temperatures and humidity. Consequently, Florida beekeepers must remain vigilant with their disease/pest control practices. For more information on Florida honey bee pests and diseases, see the EDIS subtopic Bee Pests.

Bears inhabit many areas of Florida and pose a risk to managed bee colonies. Beekeepers are encouraged to install bear fences around their colonies to mitigate interactions with bears. See the publication Florida Bears and Beekeeping for more information.

African honey bees (AHBs) (Boxes 1 and 2) have been found in Florida since at least the early 2000s. These bees express heightened defensive behavior, nest in high densities in southern Florida, and have ushered in significant changes to bee-related policy and management practices. For more information on AHBs in Florida, see the publications under the Africanized Honey Bee topic and https://www.fdacs.gov/Consumer-Resources/Health-and-Safety/Africanized-Honey-Bees.

What's in a name?

In popular literature, "African," "Africanized," and "killer" bees are terms that have been used to describe the same honey bee. However, "African bee" or "African honey bee" most correctly refers to Apis mellifera scutellata when it is found outside of its native range. A.m. scutellata is a subspecies or race of honey bee native to sub-Saharan Africa, where it is referred to as "Savannah honey bee" given that there are many subspecies of African honey bee, making the term "African honey bee" too ambiguous there. The term "Africanized honey bee" refers to hybrids between A.m. scutella and one or more of the European subspecies of honey bees kept in the Americas. There is remarkably little introgression of European genes into the introduced A.m. scutellata population throughout South America, Central America, and Mexico. Thus, it is more precise to refer to the population of African honey bees present in the Americas as "African-derived honey bees." However, for the sake of simplicity/consistency, we will refer to African-derived honey bees outside of their native range as "African honey bees" or "AHBs."

Honey bees nesting on your property?

The state of Florida recommends that nuisance honey bees (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in1005 and https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in790) found nesting outside of hives managed by a beekeeper (like those nesting in tree cavities, walls, water meter boxes, etc.) be either (1) removed from the nest site by a registered beekeeper (https://www.fdacs.gov/Agriculture-Industry/Bees-Apiary/Beekeeper-Registration) or trained Pest Control Operator (PCO) or (2) eradicated by a PCO. Consult the publication "Choosing the Right Pest Control Operator for Honey Bee Removal: A Consumer Guide" (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in771) for advice on hiring a PCO. It is the responsibility of the property owner to deal with an unwanted swarm (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in970) or colony of honey bees. To find a registered beekeeper or PCO who offers removal or eradication services, visit https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/honey-bee/beekeeper-resources/bee-removal/. For more information on African honey bees, see https://www.fdacs.gov/Consumer-Resources/Health-and-Safety/Africanized-Honey-Bees or https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/entity/topic/africanized_honey_bee.

Another issue of concern for Florida beekeepers is their bees' interactions with pesticides in the environment. For more information read the publications Minimizing Honey Bee Exposure to Pesticides, Mosquito Control and Beekeepers, and Pesticide Labeling: Environmental Hazards Statements.

The warm temperatures also mean that many colonies do not enter a dormant period, as colonies typically do in late fall/winter in more temperate climates. Thus, they tend to use a lot of resources, particularly honey and pollen, to fuel their increased yearly activity. For detailed information on pollen nutrition see The Benefits of Pollen to Honey Bees.

Abiotic stressors impact colonies in Florida as well. Localized flooding can be problematic in some parts of Florida, especially during rainy and hurricane seasons. High winds common during tropical storms or hurricanes are hazardous in Florida. Colonies may need to be moved to higher ground before tropical storms or hurricanes. Prepare hives for strong storms by using ratchet straps or ropes to secure supers together. Read more in the publication Preserving Woodenware in Beekeeping Operations.

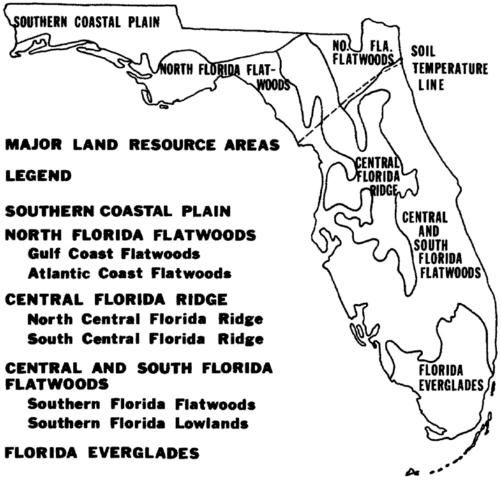

Important Nectar-Producing Plants

Florida is characterized by several major land resource areas (Figure 1). The extreme northern and western (panhandle) regions are dominated by two areas, (1) the south coastal plain, which extends some distance into Alabama and Georgia, and (2) the north Florida flatwoods. The principle vegetation mix in both areas is evergreen and deciduous forest consisting of long and short leaf pine, oak, and hickory in the uplands and cypress and gum in poorly drained areas.

The bee forage in these areas is varied and includes tulip poplar, gallberry, saw palmetto, gopher apple, cabbage palm, partridge pea, and blackberry. Trailing Chinquapin, flat-topped goldenrod, summer farewell, Spanish needles, and Mexican clover may also be found, especially in disturbed areas. Other nectar and pollen sources include white and black (summer) ti-ti, crimson clover, red maple, and willow. The Apalachicola river area supports tupelo trees, one of Florida's best-known nectar sources.

The central Florida ridge is an area of deep, well-drained soils of low natural fertility. Many of the plants found in both the southern coastal plain and north Florida flatwoods are also found here, but are often limited in distribution. Gopher apple, prairie sunflower, Nutall's thistle, and buttonbush are all found in central and south peninsular Florida and are reliable minor sources of nectar. Some cultivated plants in the area, such as various citrus varieties, loquats, and kumquats, may also provide nectar and pollen. Many Florida beekeepers use their bees to pollinate blueberries, watermelons and other cucurbit groups (squash and cucumber).

The central and south Florida flatwoods lie south of the soil temperature line (Figure 1) and surround the central Florida ridge. Often surface drainage is poor in the flatwoods, and underlying hardpan in some areas prevents free water movement upward or downward, making drought and flooding more damaging. Here longleaf pine prevails, but an understory of small shrubs, some of which are excellent nectar sources, also exists.

In swampy locations, cypress and gum predominate. The bee forage is dominated by saw palmetto, cabbage palm, and gallberry, all major nectar sources. Some invasive plants like Brazilian pepper and the punk tree (Melaleuca) can be good nectar sources, especially in late summer/fall, though there are state efforts to eradicate these plants. Spanish needles and flat-topped goldenrod are also excellent fall nectar plants found in the Florida flatwoods. In addition, from about Hernando County southward, coastal mangrove swamps on the west coast maintain populations of white and black mangrove, the latter a significant nectar producer. This part of Florida is also known for pennyroyal and seagrape, two minor nectar sources. Both may be good producers in localized areas.

The Florida Everglades is found south and west of Lake Okeechobee. This is the major winter vegetable-growing region in the state where pole beans, string beans, celery, potatoes, peppers, squash, watermelons, lettuce, and tomatoes are produced. In addition, tropical crops like sugarcane, avocado, guava, limes, and mango are cultivated. Natural plants like Spanish needles, clovers, gallberry, saw palmetto, and cabbage palm are also present. Coastal areas are dominated by mangrove, and the Brazilian pepper and Melaleuca are also well established in this area.

Seasonal Colony Growth and Management

Bee colonies should be inspected most frequently in the spring for signs of disease and pests, pattern of brood (indicating queen quality), population size, and food supply. The queen may begin laying eggs for spring, if she ever stopped, as early as December. Nectar and pollen from early-blooming plants such as pennyroyal, red maple, and willow will stimulate colony growth in late December and through January. Slow-growing colonies can be fed sugar syrup or a pollen supplement at this time to stimulate growth in preparation for honey production during later blooms. This is also a good time to treat for some pests and diseases, such as Varroa, before the larger blooms. Continue to monitor colonies in mid- and late spring for signs of disease, queen problems, or swarming as the population grows. This is also primarily when honey is produced. Read Swarm Control for Managed Beehives and Using Nucs in Beekeeping Operations for more information about swarm control, or see the EDIS topic Bee Pests for information about pests and diseases.

Mid-summer is generally a time of colony decline. Few plants are blooming in the north and west portion of the state, although some more tropical parts may have blooms year round. Additionally, partridge pea, Mexican clover, and Brazilian pepper bloom in late July and early August. Monitor colony food stores during this time because starvation is a real possibility. Provide water to colonies if no local source is available, and take measures—such as reducing the size of the entrance to the hive—to control robbing. Read the publication Robbing Behavior in Honey Bees for more information on controlling robbing.

There is another nectar flow in many parts of Florida in the fall. The most significant blooms consist of aster, golden rod, spanish needles, summer farewell, and Brazilian pepper. Fall colony management is similar to spring colony management. Monitor and treat for diseases and pests, monitor for queen health, and monitor population size to prevent swarming.

Monitor colony food stores in the winter when there is little to no nectar or pollen available. A super full of honey may be placed on a hive to provide extra food. Sugar syrup may be used as an alternative food source. Remove queen excluders from hives that are being fed using honey supers in the winter so that the queen can move into the super if necessary.

Read the Florida Beekeeping Management Calendar for more detailed information about yearly management.

Regulations for Keeping Bees in Florida

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Plant Industry (FDACS-DPI) is the governing body that oversees the rules and regulations of keeping honey bees in Florida. Florida has a mandatory registration law, thus each beekeeper having honey bee colonies within the state must register with the Department. Registered beekeepers will be issued a unique firm number; this number must be permanently marked on each of their hive bodies for identification purposes. Beekeepers' registrations must be renewed annually, and all registered beekeepers will undergo routine inspection for symptoms of American Foulbrood by an FDACS apiary inspector. New honey bee colonies moved into Florida are also subject to inspection by the Florida Department of Agricultural Law Enforcement. Any bees or equipment found to be infested with specific pests, including American Foulbrood or African honey bees, will need to be treated or destroyed if treatment is not possible. Adulterated honey product will be confiscated. Visit the FDACS Beekeeper Registration page for more information.

With permission of the land owner or legal representative, managed honey bee colonies in Florida may be located either on agricultural land or on non-agricultural land that is integral to a beekeeping operation. FDACS holds the authority to preempt any local ordinances that prohibit beekeeping except for those adopted by homeowners' associations (HOA) or deed-restricted communities. Any colonies kept on non-agricultural properties must follow the Best Management Requirements (BMR) for Maintaining European Honey Bee Colonies to be in compliance with the Beekeeper Compliance Agreement (FDACS-08492). For further explanation see the publication Best Management Practices for Siting Honey Bee Colonies: Good Neighbor Guidelines.

Information on the laws surrounding honey production and bottling can be found in the publication Bottling, Labeling, Selling Honey in Florida. For tips on crime prevention in beekeeping operations, see the publication Theft, Vandalism, and Other Related Crimes in the Beekeeping Industry: A Guide for Beekeepers.

References

Bee Informed Partnership [BIP]. 2016. Management Survey Results (2014–2015). https://beeinformed.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Demographics-Compilation.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). 2022. 2022 Census of Agriculture, United States Summary and State Data. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Surveys/Guide_to_NASS_Surveys/Bee_and_Honey/

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). 2022. Southern Region News Release: Honey. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Regional_Office/Southern/includes/Publications/Livestock_Releases/Bee_and_Honey/2022/HONEY2022.pdf