Public and private partnerships to store stormwater runoff on privately owned lands have become more popular in south Florida over the last decade. The goal of these partnerships is to improve water quality by reducing the movement of stormwater runoff from these lands into waterways and ultimately sensitive aquatic ecosystems such as lakes and estuaries. Managing water on privately owned lands is one way to reduce the nutrient and sediment loads discharged into waterbodies and coastal estuaries. Water storage is a potentially cost-effective approach for retaining runoff and reducing the excessive nutrient loads that afflict many of Florida’s watersheds. This publication introduces water storage strategies known as Dispersed Water Management (DWM) and Water Farms (WF) and describes the process that a private landowner should follow to obtain a permit and begin a water storage agreement with the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) and the St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD).

Water Storage Strategies

Water storage strategies involve an agreement between a private landowner and a water management district for the storage of stormwater for a defined period. The management districts incentivize landowners annually for the use of their land to manage stored water. Under this agreement, the district, cooperatively with the landowner, evaluates and documents water storage, water quality improvements, and environmental benefits of each submitted water storage project request. The main purposes of DWM and WF are to retain or detain water for periods of up to ten years. An advantage of these agreements is that the landowner can go back to crop production or ranching after the ten years have passed.

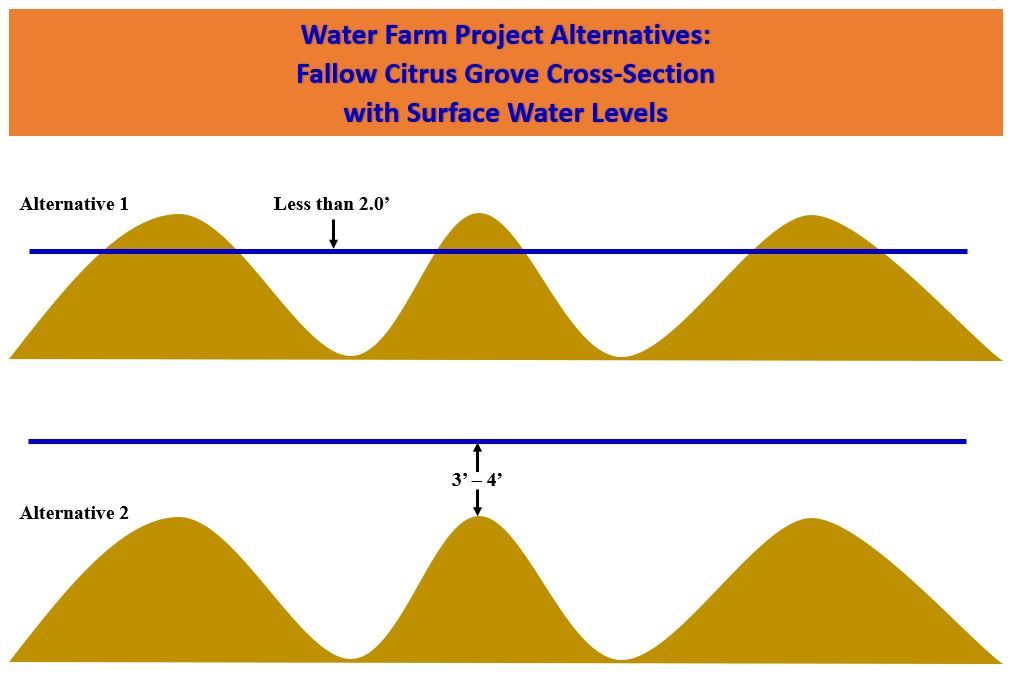

Although the purposes of DWM and WF are similar, the distinction between them is dependent on location and prior land use. The DWM projects are characterized as lands usedmostly for range cattle or crop management. The term “water farming” was coined by the Indian River Citrus League, in reference to an agricultural entity providing water retention or water storage on fallow citrus lands.DWM and WF can be quickly implemented and placed onvirtually any land that has appropriate soil and topography and is located within a priority area. The configuration of a WF on fallow citrusland usually encompasses raised beds separated by 30–60 ft, which might serve as a windbreak during hurricane season. The amount of water held in these storage systems is conditional to the field configuration and initial engineering assessments. Generally, shallow levels of water between 4 and 6 feet deep, or deeper levels up to 12 feet, are typical for storage. Besides stormwater, some of the water stored includes water pumped onto the site from public canals or rivers. Although the storage capacity of DWM and WF depends on factors such as soil type and infiltration rates of the project site, the estimated annual volume of water stored on a 60-acre WF could be around 800 acre-feet (SFWMD 2018). In collaboration with design engineers, the SFWMD conducted a ten-year study to develop strategies for the storage capacity of water farms dependent upon the water surface levels. Figure 1 displays a cross-sectional drawing of the bedrows andfurrows in a citrus grove in alternating scenarios. The SFWMD study found that in Alternative 1 (with a water level under 2 feet), every 1,000 acres of fallow grove used for water farming provided a yearly increase in retention volume of 1,300 to 1,900 acre-feet. Alternative 2 (used in more intensive storage with a water level of 3–4 feet)sustained an increase range of 1,700 to 2,500 acre-feet of annual storage volume.

Credit: Adapted from Oakley (2016)

Water storage strategies on private lands offer many environmental and economic benefits, including:

- Valuable groundwater recharge for water supply

- Improved water quality and reduced nutrient and sediment movement

- Retention and detention of drainage waters

- Nourishment of overutilized soils

- Enhanced plant and wildlife habitat

- Maintenance of private lands on the tax rolls, while still producing food and fiber

- An additional revenue stream for landowners as an incentive for environmental services

- Support of local economies by incentivizing landowners for program participation

- Reduced construction costs compared to permanent infrastructure development

- Provision of future water supply for the growing population of south Florida

Why do the water management districts want to have water storage on private lands?

Water management districts work with a coalition of agencies, environmental organizations, ranchers, and researchers to enhance opportunities for storing excess surface water on private and public lands. These partnerships have made thousands of acre-feet of water retention and storage available throughout the greater Everglades system. When water levels in south Florida are higher than normal during the rainy season, the district can utilize this storage while taking further actions to capture and store water throughout the regional water management system. Managing water on these lands is one way to help reduce the amount of water delivered into Lake Okeechobee and/or discharged to the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries for flood protection during high water conditions. A study of three WF projects implemented in the SFWMD showed the farms captured a combined yearly average of 9,400 acre-feet of water that would have been dispersed throughout the St. Lucie watershed. WF projects in the SJRWMD have been collectively estimated to capture nearly 9,000 pounds of phosphorus and nearly 60,000 pounds of nitrogen each year and to treat an average of 23 million gallons of water daily that would otherwise flow to the Indian River Lagoon (SFWMD 2018).

Landowners typically join the program by way of partnerships with the WMD’s cost-share cooperative programs, easements, pay-for-performance, or payment for environmental services. These programs and services encourage the partnerships by assisting landowners with project design and construction as well as providing monetary payments for the use of their land for water storage and retention.

Initial Steps to Establish a Water Storage Agreement

Based on the private land location, landowners can initiate an agreement process with the SFWMD or the SJRWMD according to the following guidelines.

South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD)

- The district opens a call for water storage project proposals (https://www.sfwmd.gov/sites/default/files/documents).

- The landowner revises and submits the required documentation.

- The SFWMD evaluates and approves proposal submissions.

- The SFWMD uses the water retention model to determine the annual acre-feet of water retention at the proposed site. This value is the base to calculate the cost per acre-foot of water stored (https://www.sfwmd.gov/science-data/sfwmm-model).

- The SFWMD negotiates the DWM cost with the landowner and generates an agreement.

- After the agreement is made, landowners should consult the latest version of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Environmental Resource Permit Applicant’s Handbook for the required permits (https://www.sfwmd.gov/sites/default/files/documents/swerp_applicants_handbook_vol_i.pdf).

- The water storage agreement is executed (SFWMD 2014).

St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD)

- The landowner should verify the proposed land is part of the SJRWMD priority locations (e.g., if the land is part of a Basin Management Action Plan) (https://floridadep.gov/dear/water-quality-restoration/content/basin-management-action-plans-bmaps).

- The landowner provides an initial estimation of how much the WF project might cost.

- The landowner contacts SJRWMD to determine if the project is viable and if there are opportunities for cost-share.

- The landowner revises and submits the required documentation to the district.

- SJRWMD evaluates the project based on potential funding sources and district priorities at the time of application and determines opportunities for cost-share.

- The WF project is approved, and a cost-share is negotiated.

- The landowner provides engineering designs for approval by the SJRWMD.

- The SJRWMD evaluates and approves the engineering design. After approval, the landowner should apply for the following required water and construction permits:

-

- Consumptive use permits: https://www.sjrwmd.com/permitting/CUP

- Environmental resource permit: https://www.sjrwmd.com/permitting/ERP

- Archaeological research permit: https://dos.myflorida.com/historical/archaeology/public-lands/research-permits/

9. The water storage agreement is executed (SJRWMD, personal communication).

Summary

Water storage projects expand the capabilities of the water management districts to manage and improve water quality by retaining excess water that would otherwise impact Florida’s estuaries, rivers, and other freshwater systems. These projects also provide a host of other important environmental benefits that include enhancing wildlife habitats, preserving farmland from urban development, expanding public recreational opportunities, creating shallow groundwater recharge, and keeping land on local tax rolls so the land continues contributing property tax dollars to the community. State-funded cost-share programs provided by the South Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District pay landowners for their contribution to their dispersed water management programs.

By allowing landowners to be part of the solution, dispersed water projects avoid expensive land acquisition costs. They also take less time to construct once permitted and cost less to operate than large public water projects. In partnership with the state, water storage projects greatly expand the capacity to manage excess surface water on private land. These projects provide a proven, cost-effective mechanism to protect our water resources and the environment. Many such projects have been implemented with remarkable success over the last decade.

References

Florida Department of Environmental Protection. 2020. Environmental Resource Permit Applicant’s Handbook, Volume I. https://www.fdep.gov/swerp_applicants_handbook_vol_i.pdf

Oakley, M. 2016. In Audit of Dispersed Water Management Program, prepared by the Office of the Inspector General. South Florida Water Management District. https://www.sfwmd.gov/sites/default/files/documents/audit_disbursed_water_management_14-07.pdf

South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD). 2014. Audit of Dispersed Water Management (DWM) Program. https://www.sfwmd.gov/sites/default/files/documents/audit_disbursed_water_management_14-07.pdf

South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD). 2020. Strategic Plan: 2021–2026. https://www.sfwmd.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2021-2026_Strategic_Plan_Main%20Document_Final_2021-2026_STRATEGIC_Review_Version.pdf

South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD). 2018. Water Farming Pilot Projects Final Report. https://www.sfwmd.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Water_Farming_Pilot_Projects.pdf