Introduction

Butterfly gardening and watching continue to grow in popularity nationwide as more and more people plant butterfly-attracting plants in their yards. Community ButterflyScaping is a broader concept that embraces Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ practices within communities and seeks to connect people with their landscaped and natural surroundings.

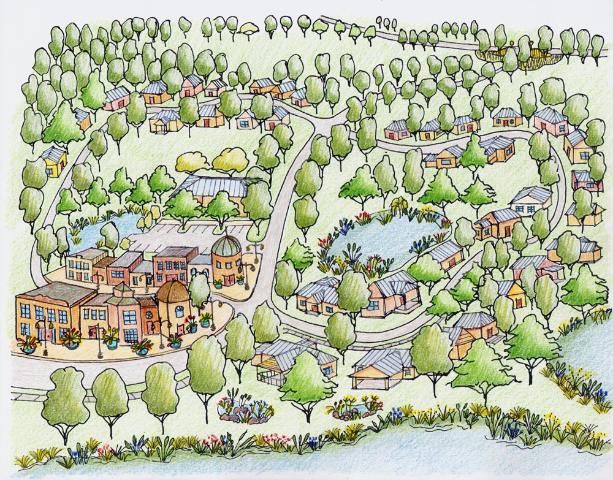

Credit: Gail Hansen, UF/IFAS

In Community ButterflyScaping, the vegetation in common areas, stormwater management systems, undeveloped areas, and yards works together to form large-scale habitats attractive to butterflies, pollinators, birds, and other local wildlife. These habitats are known as Community ButterflyScapes. Figure 1 is an artist's rendering of a Community ButterflyScape. Butterfly gardens or other existing landscaped or natural elements can be components of Community ButterflyScapes.

Community Butterflyscapes encompass all butterfly-attracting vegetation—from canopy trees to smaller trees, shrubs, perennials, grasses, groundcovers, and pond vegetation. Such vegetation provides forage (pollen and nectar), larval host resources, shelter, pollinator nesting sites, and other essential elements necessary for butterfly growth and reproduction.

Community ButterflyScapes also can be practical landscapes that potentially lower maintenance costs through reduced mowing and minimal or no irrigation, fertilizers, and pesticides.

Finally, developers and community associations alike may want to consider a Community ButterflyScaping theme under the umbrella of Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ principles. Such landscapes can be marketing tools for communities that aim to conserve and protect water quality as they serve the goals of Florida-Friendly Landscaping™.

Preserve Existing Vegetation

Many butterflies occur naturally in communities and neighborhoods. Both established communities and those planned for development can enhance habitat for Community ButterflyScapes simply by preserving or planting trees, shrubs, grasses, and groundcovers that provide food sources, shelter, and habitat for butterflies.

Host and Nectar Plants

Nectar plants provide food resources for adult butterflies. Host plants are plants on which adult butterflies lay their eggs and on which developing larvae feed.

While butterflies need both host and nectar plants to complete their life cycles, an emphasis on host plants encourages butterflies to breed within given areas. Each kind of butterfly uses a limited range of host plants, but many host plants also provide nectar.

While some of the "wilder" plant species discussed in this publication could be difficult to find at nurseries, many of them may already exist in the community. See the "Additional Resources" section of this publication for more information.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principles and Community ButterflyScaping

Community ButterflyScaping incorporates all nine principles of Florida-Friendly Landscaping™: right plant, right place; water efficiently; fertilize appropriately; mulch; attract wildlife; control yard pests responsibly; recycle; reduce stormwater runoff; and protect the waterfront. These principles are designed to help protect Florida's natural resources by encouraging landscapes that require minimal to no supplemental water, fertilizers, and pesticides. For more information, visit http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/. Each Florida-Friendly principle can incorporate a way to attract butterflies, adding interest to the landscape while helping protect Florida's resources.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #1: Right Plant, Right Place

Butterfly host plants span a variety of habitats, soil, and moisture conditions, making for a rich, diverse mosaic across a Community ButterflyScape. Knowing the preferred conditions in which the plants grow is the key to success in any landscape.

Whether native or non-native, butterfly-attracting plants placed in the right spot thrive and require minimal to no supplemental water, fertilizer, and pesticide. One way to help ensure the soil and moisture conditions fit the plant's needs in the community is to have the soil tested. UF/IFAS Extension offices can provide soil sample bags and instructions on how to submit samples for testing.

Any plant can be Florida-Friendly if it matches site conditions and isn't an exotic, invasive plant. For a reference list of plants and their requirements, visit: https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/homeowners/publications.htm

Common Areas

Common areas include areas within town centers, around clubhouses, along sidewalks, in medians, and along main roads. Table 1 lists host trees, shrubs, perennials, and grasses suitable for common areas. Plantings in common areas set the tone for the community. Residential yards often mirror vegetation in these areas.

Accent and specimen trees can be butterfly hosts, as can colorful shrubs, perennials, native grasses commonly used in landscaping, and groundcovers (see Table 3).

Yards

ButterflyScaping emphasizes the planting of nectar sources in residential yards to attract nearby butterflies when there is a concentration of host plants within the community. Table 2 details nectar sources.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #2: Water Efficiently

All plants, both native and non-native, need irrigation to become established. Florida-Friendly plants thrive on minimal irrigation. Established groundcovers that can be mowed and low-growing shrubs that attract butterflies can reduce maintenance. If planted in the right place, most need little to no irrigation and minimal mowing.

Groundcovers

Butterfly-attracting groundcovers can be used in concert with turf, alone as monocultures, or mixed to create a wildflower meadow. Such groundcovers can be used in yards, on roadside slopes, in medians, in dry retention areas, and along pond edges. Table 3 provides suggestions for host groundcovers.

Test the growth and appearance of groundcovers in a patch first to see how they perform. In the more northerly, cooler parts of Florida, groundcovers become dormant. If desired, cover them with a thin layer of mulch during colder months to enhance aesthetics. Groundcovers rebound with warmer temperatures and spring showers.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #3: Fertilize Appropriately

If growing the butterfly plants in the right place based on their water requirements and nutritional needs, little or no fertilizer may be necessary after establishment. Always use slow-release nitrogen when fertilizing and never apply fertilizer within 10 ft of a water body.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #4: Mulch

Mulch gives off radiant heat, providing a platform for basking butterflies to warm their bodies before flight.

Maintaining a 3-in. layer of mulch helps retain soil moisture, prevents erosion, suppresses growth of unwanted plants, and accents the landscape. In Community ButterflyScapes, mulch provides continuity to the appearance of the landscape when establishing groundcovers. Use naturally occurring mulches, such as leaves, compost, or recycled mulch. The Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Program does not recommend use of cypress mulch, as its origins may be difficult to determine. Don't allow mulch to touch the foundation of the house; this keeps moisture to a minimum and deters termites.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #5: Attract Wildlife

Community ButterflyScaping offers the community a way to preserve and enhance habitat to help offset habitat loss in the state. Butterflies often are considered a flagship of environmental health, and they invite people to investigate and connect with their natural surroundings.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #6: Control Yard Pests Responsibly

Only a few plants are eaten to the ground by butterfly larvae, such as milkweed, passionflower, parsley, dill, and fennel. However, these plants often rebound several times before they must be replaced. In other cases, especially with trees, most shrubs, and grasses, feeding damage is barely noticeable, and it encourages healthy, new plant growth.

When Community ButterflyScaping, it's important to differentiate between common landscape insect pests and butterfly larvae. Since Community ButterflyScaping provides habitat for butterflies, proper management of insecticides is essential. By implementing integrated pest management (IPM), residents and landscapers learn to identify pests, scout for them, and use soft pesticides—such as oils, soaps, and botanicals—to spot treat pests only when necessary.

Indiscriminate use of insecticides can harm people, pets, beneficial organisms, and the environment. Routine, scheduled spraying is not an IPM practice nor is it compatible with Community ButterflyScaping. For more information about IPM, visit http://ipm.ifas.ufl.edu/index.shtml.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #7: Recycle

Compost yard waste, vegetative waste from common areas, and vegetable scraps from the kitchen to use in the Community ButterflyScape. Compost attracts butterflies because it is nutrient rich. Male butterflies sip on moist earth and sand, gathering salts and proteins that they pass to females during mating. Females use these nutrients to support egg production. Muddy or moist spots attract "puddling" males that use their proboscis (tongue) to acquire the nutrients. Compost enriches puddling areas.

Locate puddling patches near high-traffic areas so people can enjoy this fascinating butterfly behavior. Frame the patches of bare earth with rocks or landscape timbers for accents.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #8: Reduce Stormwater Runoff

Increasing porous surfaces, planting trees to intercept rainfall, creating rain gardens, and vegetating swales, dry retention areas, roadsides, and undeveloped areas all help reduce stormwater runoff. Less stormwater means less chance nutrients will reach water bodies.

Trees

Preserving and planting trees to create a canopy that intercepts rainfall (Seitz and Escobedo 2008) and increasing porous surfaces with Community ButterflyScape plantings are great ways for developers, builders, and existing communities to fulfill one of the prime goals of Florida-Friendly Landscaping™: Reduce and clean up stormwater.

Trees, such as sassafras (which hosts spicebush swallowtail), wild cherry (which hosts tiger swallowtail), and willow (which hosts viceroy) are often cleared. Wild cherry and willow produce nectar that attracts many kinds of butterflies. Table 4 lists these and other host trees.

Credit: Kathy Malone

Credit: Kathy Malone

Rain Gardens

Consider installing a rain garden as part of the Community ButterflyScape. Rain gardens, which are natural or manmade depressions that collect stormwater, are landscaped with plants that tolerate dry to wet extremes. Table 5 contains a list of host and nectar plants that survive such extremes. For general information on rain gardens, see the Florida Yards and Neighborhoods Handbook at http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/materials/handbook.pdf.

Swales

Swales, which are roadside depressions, absorb nutrients from runoff. Low-growing plants used in the rain garden also are suitable in swales as long as they do not compromise stormwater function.

Dry Retention Areas

Dry retention areas are shallow, sculpted basins within developments that capture excess stormwater, but which usually stay dry much of the year. Generally, they are many acres in size and, often, they are maintained. They present a fantastic opportunity to convert them into a Community ButterflyScaping element.

Placing butterfly host vegetation in such areas—especially low-growing vegetation that can be mowed occasionally—could lower a community association's maintenance bill through reduced maintenance. Possibilities include a wildflower meadow, but make sure the meadow includes a diversity of host plants. Examples are passionflower, fogfruit, plants listed in Table 5, and other naturally occurring species as listed in Table 7. Again, an important concept of Community ButterflyScaping is to recognize host plants that already exist and incorporate them into the Community ButterflyScape. Accents of hosts trees and shrubs can be added as well.

Consider a cascade of layered vegetation—from trees, to smaller trees, to shrubs, and finally groundcovers. Vertical layers attract wildlife by fostering protection, creating a niche for birds and other wildlife and adding diversity to the landscape.

Take care to keep dry retention areas functional with respect to the role they play in stormwater management. Be sure to check with local and regional regulatory agencies and look into community association restrictions when landscaping a dry retention area.

Tips for Landscaping Dry Retention Areas

Side slopes—Bunchgrasses and groundcovers. Accent with butterfly host trees.

First (top) layer—Trees and small trees. Be cognizant of residents' views when selecting plants. However, dry retention areas are at lower elevations, so even tall trees may be acceptable.

Second layer—Shrubs and grasses. To add interest and diversity, add grasses as a visual break between the second and third layers and as a visual tie-in to the side slopes.

Third (bottom) layer—Groundcovers and wildflower seed mixes. Make sure to plant seed mixes appropriate for the locality and grown locally or in Florida. Create nature trails through wildflowers and shrubs by mowing pathways.

Figures 4 and 5 show an example of a tree that can be used in North Florida to attract and host the uncommon Sweadner's juniper hairstreak. Plant red cedar in groups or rows, keep the lower limbs intact, and do not place mulch under the trees. The tree's lower limbs, along with fallen needles, are necessary for the life cycle of the hairstreak (Pence 2005).

Table 6 lists suggestions for host plants for each layer of plantings in dry retention areas.

Credit: Kathy Malone

Credit: Kathy Malone

Nonlandscaped Roadsides and Undeveloped Areas

In communities with nonlandscaped roadsides and undeveloped areas, host plant seeds may lay dormant and sprout when conditions are right. Table 7 lists a number of these. Additional undeveloped areas include conservation buffers, easements, wetland jurisdictions, dry retention areas and detention ponds, recreational trails and pathways, wildlife corridors, and vacant lots. Protecting the integrity of these areas with vegetative cover helps filter and reduce stormwater runoff.

By designating areas that are not mowed frequently, residents can see which of the more obscure, weedy host wildflowers draw in butterflies. With a Community ButterflyScape as the context, plants that might otherwise be unwanted or overlooked have a purpose. It may be surprising and rewarding to see which plants emerge in these areas of interest and the butterflies that find them.

Many undeveloped areas have cudweed or fogfruit growing in them. Figures 6, 7, 8, and 9 show these host plants and their associated butterflies. Larvae of the American lady shelter themselves in the puffy blooms of cudweed. Search for larvae in the flower heads in the springtime.

Credit: Kathy Malone

Credit: Kathy Malone

Credit: Kathy Malone

Credit: Kathy Malone

How to Propagate Fogfruit

To propagate fogfruit, find a succulent, healthy stem with several leaves. Near the bottom of the stem, trim at least two leaves at the leaf nodes. Place the exposed nodes in wet, rich soil or water. The nodes will form roots. Water daily for at least a week until the plant no longer wilts between waterings. While fogfruit can grow almost anywhere, from beach dunes to pond edges, it makes a lush, dense groundcover under moist, rich conditions. It hosts the phaon crescent, white peacock (South Florida), and common buckeye.

Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principle #9: Protect the Waterfront

Plantings of groundcovers, grasses, shrubs, and trees accent ponds and enrich the landscape. Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ principles recommend a no-maintenance, 10-ft buffer of vegetation around ponds to help protect water quality. Such vegetation cleanses stormwater before it enters the water body. In addition, landscaping ordinances that require a buffer may come into effect in the next several years as local governments adopt Florida-Friendly ordinances.

Consider transforming stormwater ponds into visually pleasing and Florida-Friendly aesthetic landscapes with plantings that also attract butterflies. Groundcovers, such as fogfruit (which hosts three butterfly species and is a fantastic nectar source for many butterflies), are low growing. Low-growing vegetation helps maintain views of the water. Fogfruit can be a great no-mow alternative at the water's edge.

Check with state and local water resource regulatory agencies and look into community association restrictions before landscaping a pond.

Including a Pond Buffer in the Community ButterflyScape

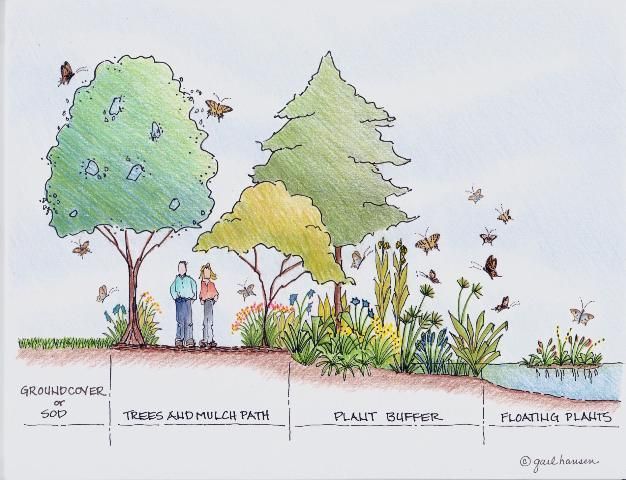

Use emergent plants around the pond's edge, then groundcovers, shrubs, and trees landward. Focus on host plants, but add a few nectar plants to enrich the diversity of the pond's edge and enhance visual appeal. Buttonbush is an excellent nectar source for large and small butterflies. Figure 10 is an artist's rendering of a cross section of a planted pond edge. Table 8 lists host plants for each section.

Besides pond edge plantings, look into an emerging new technology that helps cleanse ponds—floating vegetation mats anchored to the pond bottom. The mats can be an element of the Community ButterflyScape by using water-loving host and nectar plants.

Credit: Gail Hansen, UF/IFAS

While a variety of plants are available at some nurseries, a number of the plants may already exist by the community pond. One of the concepts of Community ButterflyScaping is to preserve existing, noninvasive host vegetation, and then plan around it.

Condominiums and other coastal communities are in a unique location to attract two beautiful coastal butterflies—the martial scrub-hairstreak and the mangrove skipper. Figures 11 and 12 show the bay cedar—the host plant for the martial scrub-hairstreak—and the butterfly.

Credit: Kathy Malone

Credit: Kathy Malone

The martial scrub-hairstreak is of concern due to loss of habitat for bay cedar which is found in coastal South Florida from Sarasota and Martin counties south through the Florida Keys. Bay cedar grows in sand dunes by the beach and slightly inland, and on barrier islands in South Florida. Residents of coastal communities have a singular opportunity to plant the versatile bay cedar in an effort to help conserve the butterfly. Bay cedar also hosts the mallow scrub-hairstreak.

Bay cedar can be used as a hedge, as it responds well to clipping, or as a specimen or border plant in beach locations. It also can be planted in a container or used as a screen when planted in a row with trunks five to six feet apart (Gilman 2007). Bay cedar is a good nectar source. Lantana, Spanish needles, and fogfruit also make great nectar sources for a variety of butterflies.

Red mangrove is the host for the mangrove skipper. Homeowners who have red mangrove near their coastal communities in peninsular Florida should consider attracting the mangrove skipper with nectar sources such as Spanish needles, citrus, and bougainvillea. Black mangrove is the host for the mangrove buckeye.

Additional Components for Community ButterflyScapes: Butterfly Bouquets and Green Walls

Butterfly Bouquets

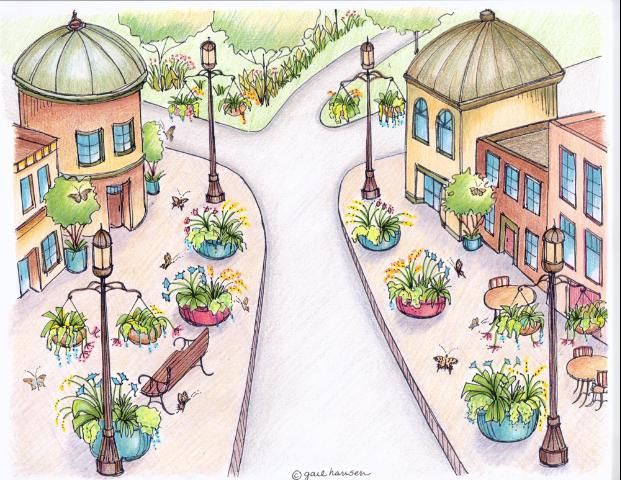

Various butterfly-attracting plants do well as potted plants. A "butterfly bouquet" is simply a combination of larval host trees and plants, with nectar accents, planted in hanging baskets and containers to attract butterflies. A display of butterfly bouquets along a town center's sidewalk presents an educational opportunity and gives passersby a delightful way to see the butterfly life cycle up close. Figure 13 depicts an artist's rendering of such a thoroughfare. Depending on the types of plants used, the display may need to be replaced annually.

Figure 14 provides an example of plants that could attract at least six different species of butterflies. It contains two hosts (passionflower and fogfruit) and three nectar sources (goldenrod, eupatorium, and firebush). Passionflower hosts the Gulf fritillary, zebra heliconian, and variegated fritillary; fogfruit hosts the phaon crescent, white peacock, and common buckeye.

Another example of a butterfly bouquet might contain colorful pentas, passionflower, fogfruit, and herbs—such as parsley, dill, fennel, and an ornamental herb known as rue. This makes a functional and attractive butterfly bouquet with host plants for eight butterfly species: Gulf fritillary, zebra heliconian (Florida's state butterfly), variegated fritillary, black swallowtail, giant swallowtail, phaon crescent, common buckeye, and white peacock (South Florida). Place a small sign in the container that mentions the bouquets are part of the Community ButterflyScape and identify the plants and butterflies that use them. Table 9 contains additional examples of plant combinations.

Credit: Gail Hansen, UF/IFAS

Credit: Eric Zamora/Florida Museum

Green Walls

By planting host plants in vertical green walls—upright garden structures that contain soil and sometimes watering systems for plants—communities can attract butterflies and feature their host plants in a unique way. Figure 15 is an example of a green wall.

Credit: UF/IFAS File Photo

Conclusion

How to Get Started with Community ButterflyScaping

A few specimen trees and shrubs and patches of host groundcovers are great ways to start Community ButterflyScapes. Small changes really make big differences, so don't feel overwhelmed. While a mass of particular host plants provides abundant food for larvae, butterflies are able to find individual host plants on which to lay eggs. Try designating one area of the community or one section of pond edge as a pilot project. See how it goes, then expand from there.

Community ButterflyScaping presents opportunities for developers, community associations, and homeowners to increase awareness of butterflies among community residents, provide critical wildlife habitat, beautify existing areas, and protect natural resources by incorporating Florida-Friendly Landscaping™. Table 10 shows how Community ButterflyScaping relates to Florida-Friendly Landscaping™.

Developers, community associations, and homeowners can seek recognition for Florida-Friendly Landscapes, of which Community ButterflyScapes can be a part, through the Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Program. For more information about the program, visit http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/professionals/services.htm.

Further, developers and community associations can adopt all or part of the Model Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Covenants, Conditions, and Restrictions (CCRs) prepared by the Department of Environmental Protection and the UF/IFAS Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Program. For the model CCRs, visit http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/community_association_kit.htm.

These model CCRs include considerations for long-term maintenance of Florida-Friendly Landscapes. By following maintenance practices outlined in the manual, Florida Friendly Best Management Practices for Protection of Water Resources by the Green Industries, developments and communities can help conserve water and protect water resources. For the manual, visit http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/professionals/GI-BMP_publications.htm.

Developers

Developers can identify and preserve butterfly host vegetation, enhance common grounds with butterfly-attracting host plants, create areas of interest on undeveloped lands, market their communities as Community ButterflyScapes, and provide educational opportunities.

Opportunities to put Community ButterflyScaping components to use include vegetative buffers; street rights-of-way with street trees; easements; dry retention areas and detention ponds; conservation set-asides and wildlife areas; wetland jurisdiction areas; wildlife corridors; recreational areas, such as trails and pathways; and vegetative screens. Existing host plants can be preserved, and new host plants can be added.

Community Associations

Community associations can establish community butterfly gardens, landscape common grounds with butterfly host plants, create amenities out of stormwater systems and pond buffers, and provide education to residents about Community ButterflyScaping and butterfly gardening.

Homeowners

Homeowners can participate in Community ButterflyScaping by planting nectar or butterfly gardens—with hosts and nectar—in their yards. Homeowners also can set aside part of their property as a meadow, to mow occasionally.

Table 11 is a summary list of the common host plants for the butterflies discussed in this publication.

References

Gilman, E. 2007. Suriana maritima: Bay cedar. FPS-565. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fp565

Pence, J. A. 2005. Conservation Biology of Mitoura gryneus sweadneri (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). PhD diss., University of Florida. http://purl.fcla.edu/fcla/etd/UFE0013112

Seitz, J., and F. Escobedo. 2008. Urban forests in Florida: Trees control stormwater runoff and improve water quality. FOR184. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fr239-2008

Additional Resources

To locate native host and nectar plants, consult the Association of Florida Native Nurseries or the Florida Wildflower Foundation.

Association for Native Nurseries. http://www.afnn.org/ [October 2011].

Florida Wildflower Foundation. https://www.flawildflowers.org.

Books and Online Documents

Brock, J. P., and J. Glassberg. 2005. Caterpillars in the field and garden: A field guide to butterfly caterpillars of North America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cech, R., and G. Tudor. 2007. Butterflies of the East Coast: An observer's guide. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Daniels, J. C. 2000. Your Florida guide to butterfly gardening: A guide for the Deep South. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Daniels, J. C. 2003. Butterflies of Florida field guide. Cambridge, MN: Adventure Publications.

Daniels, J. C. 2010. Wildflowers of Florida field guide. Cambridge, MN: Adventure Publications.

Daniels, J., J. Schaefer, C. Huegel, and F. Mazzotti. 2008. Butterfly gardening in Florida. WEC 22. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw057

Gerberg, E. J., and R. H. Arnett, Jr. 1989. Florida butterflies. Baltimore: Natural Science Publications.

Gilman, E., and D. G. Watson. 1993. Celtis laevigata: Sugarberry. ST-138. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/st138

Gilman, E., and D. G. Watson. 1994. Persea borbonia: Redbay. ST-436. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/st436

Gilman, E., and D. G. Watson. 2006. Fraxinus pennsylvanica 'Summit': 'Summit' green ash. ENH428. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ST269

Glassberg, J., M. C. Minno, and J. V. Calhoun. 2000. Butterflies through binoculars: A field, finding, and gardening guide to butterflies in Florida. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Minno, M. C., J. F. Butler, and D. W. Hall. 2005. Florida butterfly caterpillars and their host plants. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Minno, M. C., and M. Minno. 1999. Florida butterfly gardening: A complete guide to attracting, identifying, and enjoying butterflies. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Sprenkel, R. 2008. Getting started in butterfly gardening. ENY722. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00006501/00001/pdf

Walton, D., and L. Schiller. 2007. Natural Florida landscaping. Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press.

The nine principles of Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ and the relationship of Community ButterflyScaping components