Introduction

Snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus L.) belongs to the genus Antirrhinum consisting of species in three sections (section is a taxonomic rank below genus but above species): Antirrhinum, Saerohinum and Orontium. The section Antirrhinum comprises 19 diploid perennial species (Tolety and Sane 2011). These species are native to the western Mediterranean region and produce relatively large flowers (Oyama and Baum 2004). The name "Snapdragon" comes from the appearance of its flowers, which resemble the jaws and snout of a dragon (Figure 1). The word "Antirrhinum" is derived from Greek, where anti means "like" and rrhinum means "snout". Furthermore, its head will open when the flower is squeezed and snap shut when released, which looks like a dragon jaw opening, then snapping shut. This EDIS publication is for Florida horticulture industry professionals, nurserymen, growers and collectors looking to better understand how to plant and propagate snapdragons in Florida.

Credit: Juncheng Li, UF/IFAS

Only snapdragons in the Antirrhinum section have been domesticated, and their production as a garden plant dates back to the Roman Empire (Tolety and Sane 2011). Both Romans and Greeks thought snapdragons had magical qualities to protect them against charms and enchantments from witchcraft, and protection from illness or poisoning (Tolety and Sane 2011). Snapdragons were also planted near gates as the guardians of European castles. Wild varieties can still be found growing freely in the ruins of ancient Greece and Rome. During the Renaissance, snapdragons were believed to bring charisma, glory, honor, and social status; wearing them on one's sleeve was believed to lead to favorable receptions (Oyama and Baum 2004).

Today, snapdragons are cultivated throughout the world. They were brought to America when colonists began to populate the United States. Snapdragons are easy to grow and were given the title of "Flower of the Year" in 1994 by the United States National Garden Bureau (https://www.deseretnews.com/article/335410/FOR-FLOWERS-94-IS-YEAR-OF-SNAPDRAGON.html). Snapdragons are still popular due to their showy flowers that make eye-catching bedding and container plants (Figures 1 and 2). The flowers sit atop a long, green spike and have a wide range of petal colors, making it an excellent cut flower. In 2015, fresh-cut snapdragon sales reached $12.18 million in the US, making it a top ten fresh-cut flower (USDA 2015). In 2014 and 2015, the 'Chantilly' series and 'Madame Butterfly' series snapdragons were respectively selected as the "Cut Flowers of Year" by the Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers (ASCFG, www.ascfg.org). In addition to the value of their showy and fragrant blooms, snapdragon leaves and flowers are also used in the treatment of tumors, ulcers, inflammation, and hemorrhoids; in Russia, oil is extracted from snapdragon seeds as substitutes for olive oil (Tolety and Sane 2011).

Credit: Creech and Alfred Huo, UF/IFAS

Flowers of snapdragons used to be just white or purple, but today they come in a wide range of different colors, including white, yellow, red, pink, burgundy, bronze, and orange (Figure 1). There are four categories of snapdragons based on their height: dwarf (4–9 inches), short (9–12 inches), medium (12–24 inches), and tall (24–36 inches) (Creel and Kessler 2007). Dwarf varieties are bushy and commonly planted as border fronts, edgings, window boxes, or in mixed containers (Figures 2 and 3). Short plants are great for edging or in small beds or baskets. Medium plants are often the most popular group and can be used as border plants or as cut flowers. Tall varieties with a dominant, single-flower shoots are used as bold displays or cut flowers for fresh bouquets.

Credit: Caroline Roper and Alfred Huo, UF/IFAS

Snapdragon Cultivation

Planting Time

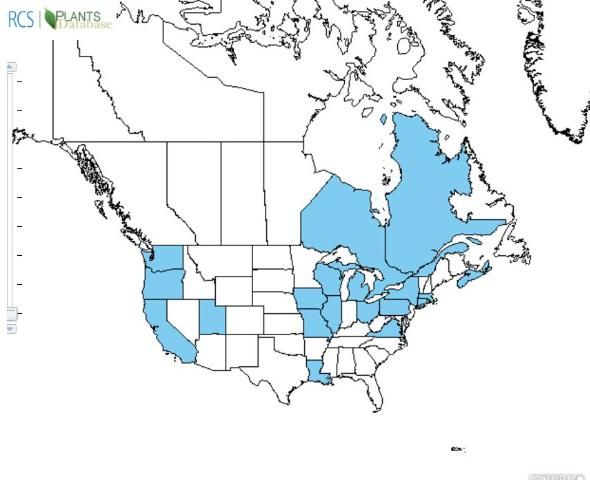

Snapdragons are cool season herbaceous perennials but grown as annuals, especially in subtropical regions. Although snapdragons can be grown across the whole country, their optimum growth temperature ranges from 65 to 75°F (18 to 24°C), which limits their production in Florida (Figure 4). In Florida, the ideal time for growing snapdragons begins in late fall through early spring. High temperatures in late spring, summer, and early fall greatly stunt their growth and result in plants with limited or no blooming.

Credit: USDA NRCS

Propagation

Seed Germination

Snapdragon production starts from seeds. Seeds are very small with approximately 6,000 to 9,000 seeds per gram (Figure 5A), and can be grown in 3–4 inch pots using rich, well-drained soil with a pH between 5.5 and 5.8. A higher pH can cause iron deficiency in snapdragons. Snapdragons are sensitive to high 'salt' levels in the growing medium, and especially to ammonium (Creel and Kessler 2007). The electro-conductivity should be less than 0.75 mS/cm, and ammonium levels less than 5 ppm (Creel and Kessler 2007). For seedling transplanting, surface sowing seeds in 384-cell trays is recommended.

Credit: Matthew Creech and Juncheng Li, UF/IFAS

If seeds are sown singly into cells, seeds can be suspended in 0.01% agar using a disposal transfer pipette to dispense a single seed into each cell. In this case, a plant preservative mixture (PPM) with a final concentration of 0.2% is recommended to minimize the fungal development (Hudson, Critchley, and Erasmus 2008a). For sowing seeds on a large scale, a waxy weigh paper can be used for spreading several seeds into individual pots; but seedling thinning will be required after germination. Seeds in pots can be exposed to air without soil cover, but soil should be kept moist during seed germination. To prevent the soil from drying out, pots can be placed in a tray with a plastic cover. Seed germination can be improved by using one of two chilling treatment methods: either by A) seed stratification, e.g. chilling the seeds suspended in 0.01% agar or water in a refrigerator for 3–5 days before sowing; or B) chilling pots with seeds in a cool room 40–47ºF (4–8ºC) for 3–5 days. Seed germination will be more uniform after a chilling treatment. Germination should occur in 7–10 days at 64–68ºF (17–20ºC) (Hudson et al. 2008a).

Vegetative Propagation through Cutting

Snapdragons can be propagated through cuttings. To propagate, first find a leaf node in the middle of a healthy stem and cut it 20–50 mm immediately below the leaf node (Hudson, Critchley, and Erasmus 2008b). Remove the leaves from the bottom two-thirds of the shoot. Dip the cut end in a solution containing 1% Indole-3 butyric acid, 0.5% 1-naphthaleneacetic acid, or in any commercial compounds like TakeRoot or FastRoot. Next, insert cuttings into rooting substrate or soil (Hudson et al. 2008b), and maintain them at high humidity (100%) or mist every 30 minutes in an enclosed container or chamber at 62–68°F (17–20°C). After approximately 2–3 weeks, rooted cuttings can be transplanted (Hudson et al. 2008b).

Plant Care

Seedling Care and Plant Transplanting

After radicles emerge, keep plants under high light (1,000 to 2,000 foot-candles). Maintain soil temperature at 65–75°F (18–21°C) and keep soil evenly moist but not saturated for rooting. Once the true leaves have developed in approximately 15–20 days, increase light levels to 5,000 to 6,000 foot-candles, because low light causes elongated feeble stems and reduces flowering. Allow soil to become relatively dry between each watering but avoid wilting. These ideal conditions will promote root growth and prevent mold development (Creel and Kessler 2007). Incorporate a layer of fine sand onto soil to strongly inhibit mold development, reduce small flies and fungus gnats, and prevent weed growth. A half strength all-purpose fertilizer such as 10-10-10 product (150 to 200 ppm nitrogen and potassium) can be applied every other watering. If growing below 65°F (18°C), avoid ammonium-based fertilizers (Hanks 2014).

Before transplanting, lower the temperature to 60–62°F (16–17°C) to make stems sturdy. Seedlings can be transplanted when they have two or three fully expanded, true leaves. Take the entire plug with a healthy seedling and transplant promptly into well-watered soil in a large pot or ground bed. Be sure to use care during transplanting to avoid root damage. For a large amount of transplants, plug trays can be held at 36–39ºF (2–4ºC) under fluorescent lights at 250 foot-candles for 14 hours per day (Creel and Kessler 2007).

Spacing

Spacing between snapdragons depends on the variety being planted. Since they produce more side branches, dwarf and shorter snapdragons should be spaced 6–12 inches apart. Single-stem tall varieties should be planted in a 4-inch diameter area to produce strong stems with superior length and bloom quality. Two layers of horizontal netting will be needed to support the stems, keeping them straight. Place the first net 4 inches above the soil level and the second at 6–8 inches above the soil level. As stems grow, continue raising the second net.

Production

After the seedlings have 3–5 true leaves (Figure 5B), maintain plants at 65–75°F (18–24°C) during the day and 56–64°F (15–17°C) at night to increase apical meristem size and encourage robust stem growth. Apply one full-strength, all-purpose fertilizer every third watering. Most snapdragons are not sensitive to photoperiod, but supplemental light to maintain long days (16 h light/8 h dark) can greatly promote flowering. In Florida, snapdragons can flower during the winter but not in the summer, suggesting that growth and flowering is influenced by high temperature instead of photoperiod. For fresh cut flower varieties, hold at 45–50°F (7–10°C) for 6 to 8 hours or overnight before cutting to extend postharvest shelf life. As cut flowers, most snapdragon varieties tend to shatter shortly after being fertilized by bees; therefore, growing plants in greenhouses may improve flower quality.

Harvesting

For fresh-cut flower varieties, cut stems when 5–7 florets are open (Figure 5E). Premature harvesting leads to poor color development and reduced flower size as flowers continue to open. Remove lower foliage and immediately place snapdragon stems in warm water at 70–75°F (21–25°C) containing floral preservatives; overnight, keep water temperatures at 45–50°F (7–10°C) for 6–8 hours. Treat with Ethyl Bloc™ to avoid shattering of ethylene sensitive varieties. Snapdragon stems can be stored at 40°F (4°C) for 3–4 days in water.

Seed Production

Most wild species of Antirrhinum are self-incompatible, meaning plants cannot be pollinated with their own pollen. The domesticated snapdragon is self-compatible and receptive to all pollen from other wild species, making it easy to breed through hybridization. Snapdragon seeds can be easily produced through self-pollination with no additional work since stamens are generally longer than stigmas. Effort and attention should be given to produce hybrid seeds from outcrossing. First, bright yellow pollen from newly dehisced anthers can be collected by scraping them from the anthers with forceps. Large amounts of pollen can be harvested by squeezing the flower and slightly tapping on waxy weight papers, which are recommended for use since the pollen is sticky. Second, fold back the flower petals of the bud before the recipient flower and use forceps to pull the filaments and remove anthers. Lastly, use a toothpick to transfer the pollen to the stigma of the emasculated flower. Alternatively, a tiny brush with pollen can pollinate multiple flowers. After pollination, flowers should be covered by mesh bags to prevent contamination with other pollen. The petals will shed off if fertilization is successful. Seeds can be harvested by shaking the pods 4–5 weeks after pollination.

Commercial Varieties for Florida

Almost all commercial varieties are not marketed as heat-tolerant, although many snapdragon varieties have been reported to be adaptable to a wide range of temperatures and can grow well in the Florida winter season (Gilman 1999). Among them, 'Floral Showers Mix' from Benary Seeds, 'Aromas' series from Goldsmith Seeds, 'Snapshot' series from Ball Seed Co., and 'Twinny Mix' series from HemGenetics perform well in Florida, especially under warm temperatures. It should be noted, however, that some of them still suffer in the Florida summer heat and will not bloom.

Future Breeding Goals in Florida

To date, no snapdragon variety has been claimed to be heat-tolerant, which makes it more challenging for Florida growers to produce snapdragons year-round. An important breeding goal is to improve heat and drought tolerance of snapdragons and produce varieties that are able to adapt to Florida climate. Producing varieties that can resist shattering due to pollination and ethylene production from cuttings would be another improvement. For fresh-cut varieties, extended post-harvest life would be long sought by growers.

Common Pests and Diseases

- Wilting and stem rot

- Wilting and stem rot are usually caused by Pythium, Rhizoctonia, or Phytophthora; seedlings will be killed by a severe infection.

- Solutions: steam or fumigate soils; spray plants with thiophanatemethyl or iprodione to control Rhizoctonia; drench soils with a solution of commercial fosetylaluminum fungicide (e.g., Aliette from Bayer CropScience).

2. Downy and powder mildews

- Mildews are apparent as gray or white powder on leaves. Seedlings are stunted due to infection. Infected plants may fail to produce flowers, and severe infections can kill plants.

- Solutions: reduce greenhouse humidity; remove dead infected tissues; spray plants with suspended sulfur or other proprietary fungicide.

3. Botrytis blight

- Pale brown dead tissues covered with gray fungi appear on shoots, leaves, and flowers.

- Solution: spray the shoots with suspended sulfur or other proprietary fungicide.

4. Rust

- Small yellow swellings form on leaves or stems and burst to release rust-colored spores.

- Solution: spray the shoots with suspended sulfur or other proprietary fungicide.

5. Root-knot nematodes

- Above-ground symptoms include yellowing, wilting, and stunting, which resemble nutrient deficiencies or drought stress. Root symptoms include short roots and distinctive swelling.

- Solutions: crop rotation; pre-plant nematicide treatments.

6. Flower Thrips

- Infested shoots and flower buds show small lesions of dead tissue, and pollen is missing from anthers, which results in discoloration and premature dropping of flowers.

- Solutions: treat foliage or flowers with insecticides as soon as thrips are found. Weekly applications may be needed until control is achieved. Apply predatory mite Neoseiulus cucumeris for biological control.

References

Creel, R., and J.R. Kessler. 2007. "Greenhouse Production of Bedding Plant Snapdragons." Alabama A&M and Auburn University, 1–3.

Gilman, E. F. 1999. Antirrhinum majus Snapdragon. FP044. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fp044

Hanks, G. 2014. "Snapdragons (Antirrhinum majus) as a cut flower crop grown in polythene tunnels." National Cut Flower Centre/HDC Information sheet 5.

Hudson, A., J. Critchley, and Y Erasmus. 2008a. "Cultivating antirrhinum." CSH Protoc. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot5051

Hudson, A., J. Critchley, and Y Erasmus. 2008b. "Propagating antirrhinum." CSH Protoc. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot5052

Oyama, R. K., and D. A. Baum. 2004. "Phylogenetic relationships of north American Antirrhinum (Veronicaceae)." American Journal of Botany. 91(6), 918–925. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.6.918

Tolety, J., and A. Sane. (2011). "Antirrhinum." In Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources, Plantation and Ornamental Crops, C. Kole (Ed.) 1–14. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

USDA. (2015). "Floriculture Crops." United States Department of Agriculture.