Abstract

Vanilla extract is the primary commercial product resulting from the mature processed fruits of Vanilla orchids. This publication is an overview of the process used to produce natural vanilla extract; it also describes the conversion of fruits (botanically termed “capsules” but often colloquially referred to as “beans” or “pods”) into extracts. This publication is intended for consumers, producers of all levels, and Extension agents. It describes each step of the natural vanilla extract production process from flower pollination through fruit harvesting, to grading, curing, and extracting of the capsules.

Introduction

At present, the Vanilla orchid genus comprises 140 known species, but only a few of these shade-loving vines are cultivated for commercial purposes, primarily Vanilla planifolia, V. pompona, V. odorata, and the hybrid Vanilla x tahitensis (Cameron 2011). Apart from these four major species, other vanilla species have local or limited uses. Natural vanilla extract is one of the most valuable spices globally (Arenas and Dressler 2010). It is worth mentioning that even though the raw capsule price is highly volatile ($5.06 to $17.86 per lb) (Hänke 2024), the price of natural extract is generally more stable ($1.37 to $6.23 per oz). Fruit source and quality influence these values.

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has a standard of identity for commercial vanilla extract as stated in 21 CFR Part 169. This regulation restricts the use of the term "vanilla bean" to cured fruits of V. planifolia and V. x tahitensis. It also defines one unit of vanilla beans as equivalent to 13.35 oz of capsules with 25% moisture content and specifies that one-fold (1x) vanilla extract is equivalent to one unit of vanilla beans per gallon of finished product with a minimum ethanol concentration of 35%.

Pollination

Most vanilla species are self-fertile (i.e., pollen from one flower can successfully fertilize it and other flowers on the same vine). While vanilla flowers attract insects and even hummingbirds for natural pollination, only bees from the Eulaema genus (Euglossini tribe, Apidae family) are effective pollinators of commercial vanilla species (de Oliveira et al. 2022). Natural pollination occurs at a low rate, even in native environments, with reported rates of only around 1% in V. planifolia and around 2.42% to 5% in V. pompona (de Oliveira et al. 2022).

The flowers of vanilla orchids occur in clusters called racemes. In each raceme, one to a few flowers open at a time, starting from the base and progressing toward the top (Arenas and Dressler 2010). Vanilla flowers are short-lived, receptive to pollination for only six to seven hours. If pollinated within this window, the flower’s ovary swells and elongates, eventually developing into a capsule. If unsuccessful, the flower drops.

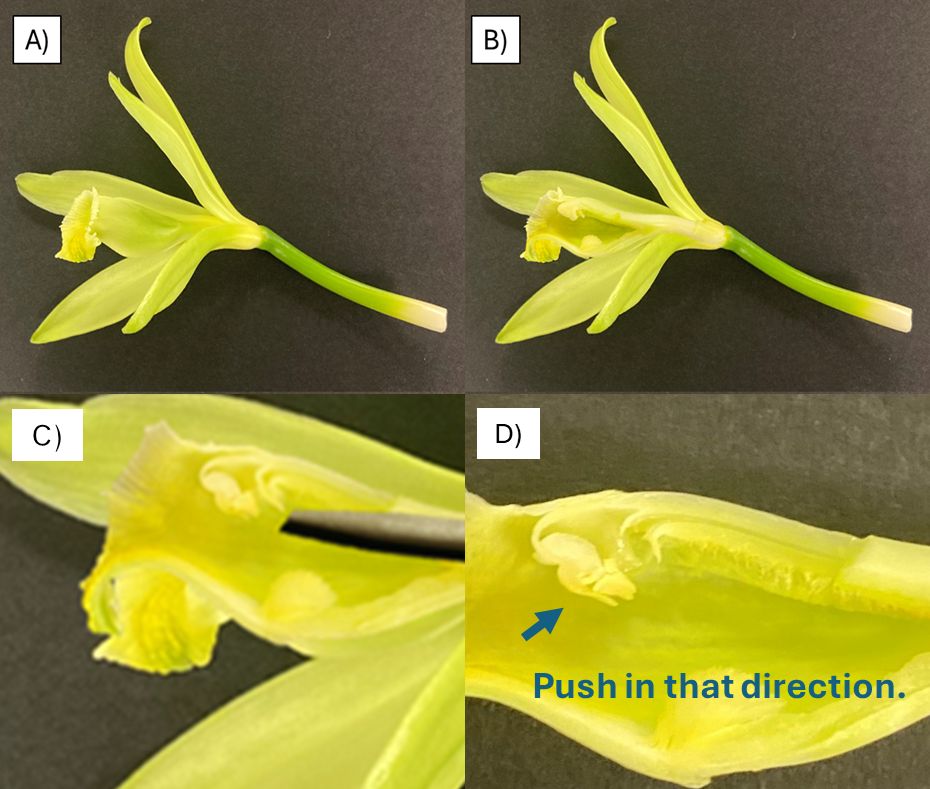

Due to low natural pollination rates, commercial vanilla plantations rely on hand pollination, a technique discovered by Edmond Albius in 1841 (Melbourne 2019). During pollination, a flap of tissue called the rostellum that separates the male tissues (pollinia) from the female tissues (stigma) must move so that these two parts of the flower can contact each other. Hand pollination involves using a slender object, such as a toothpick, to gently lift the rostellum and press the pollinia against the stigma (Figure 1).

Credit: Manuel Gastelbondo, UF/IFAS

Harvesting

Vanilla capsules reach their optimum harvest stage eight to nine months after pollination (Van Dyk et al. 2014). Capsules harvested earlier than eight months may not produce high-quality extract, while capsules harvested after nine months may split open. Splitting reduces the crop value on the commercial market since it introduces the potential for rotting. However, if the split fruits show no sign of decay and are going to be processed quickly, it may still be possible to produce a high-quality extract if the fruit has a high vanillin content.

Vanilla is harvested by either the whole raceme or single capsules (Figure 2). Although single capsule picking allows for more precise control of maturity, it is labor-intensive, and damage to the other capsules of the raceme may occur. Harvesting the entire raceme at once, by cutting at its base, is more common in commercial production.

Credit: Manuel Gastelbondo, UF/IFAS

Curing and Grading

Curing is a critical process that transforms a compound called glucovanillin, which accumulates in the green capsules, into vanillin, the compound responsible for the distinct aroma and flavor of vanilla. The quality of cured vanilla is highly dependent on the maturity of the capsules at harvest. Immature or underripe capsules will result in a lower-quality product compared to fully mature capsules because they contain much less glucovanillin. Careful harvesting and sorting of the vanilla capsules is a crucial step in the grading process.

Size, moisture, and vanillin content are key traits that determine the grading of vanilla capsules and, thus, the market value of the crop. Grade A1 capsules measure longer than 12 cm, are dark brown, and have a maximum moisture level of 30%. Lower grades include Grade A2 for split capsules and Grade B for shorter, irregular capsules with a maximum moisture level of 25% (Table 1). The calculation for moisture level derives from the percentage of weight of a cured capsule compared to its original weight when fresh. For example, a fresh capsule that loses 75% of its original weight during curing will weigh 25% of its original weight. Therefore, the moisture content is 25% (Havkin-Frenkel and Belanger 2011).

Table 1. Vanilla capsule grading standards.

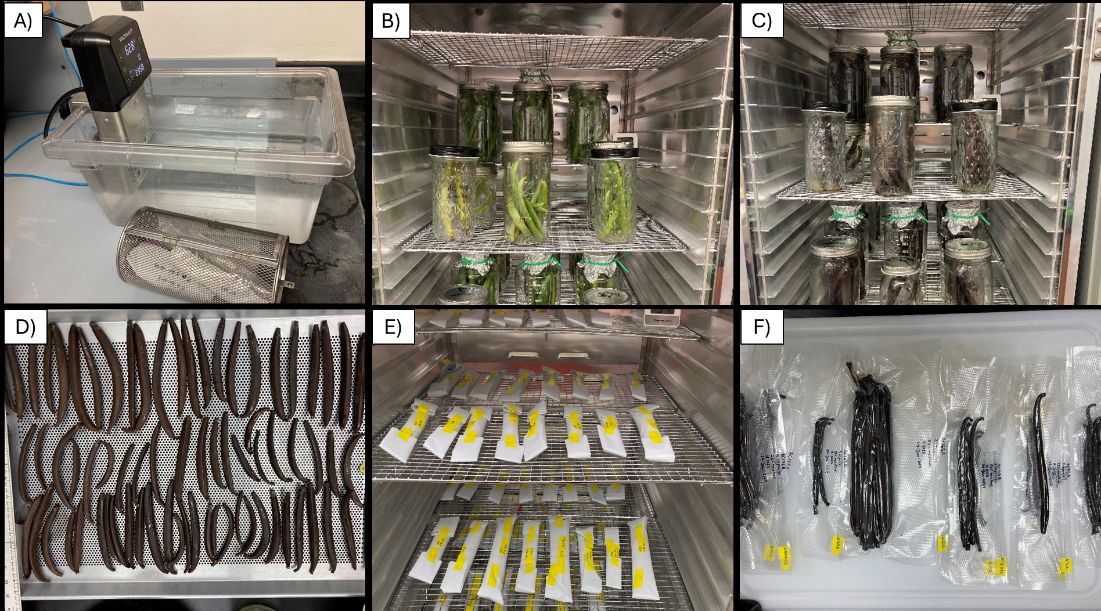

Although the curing process can vary greatly at each production site, it is generally performed in five steps, as described in Table 2 and illustrated by Figure 3.

Table 2. Curing process steps.

Credit: Manuel Gastelbondo, UF/IFAS

Extraction

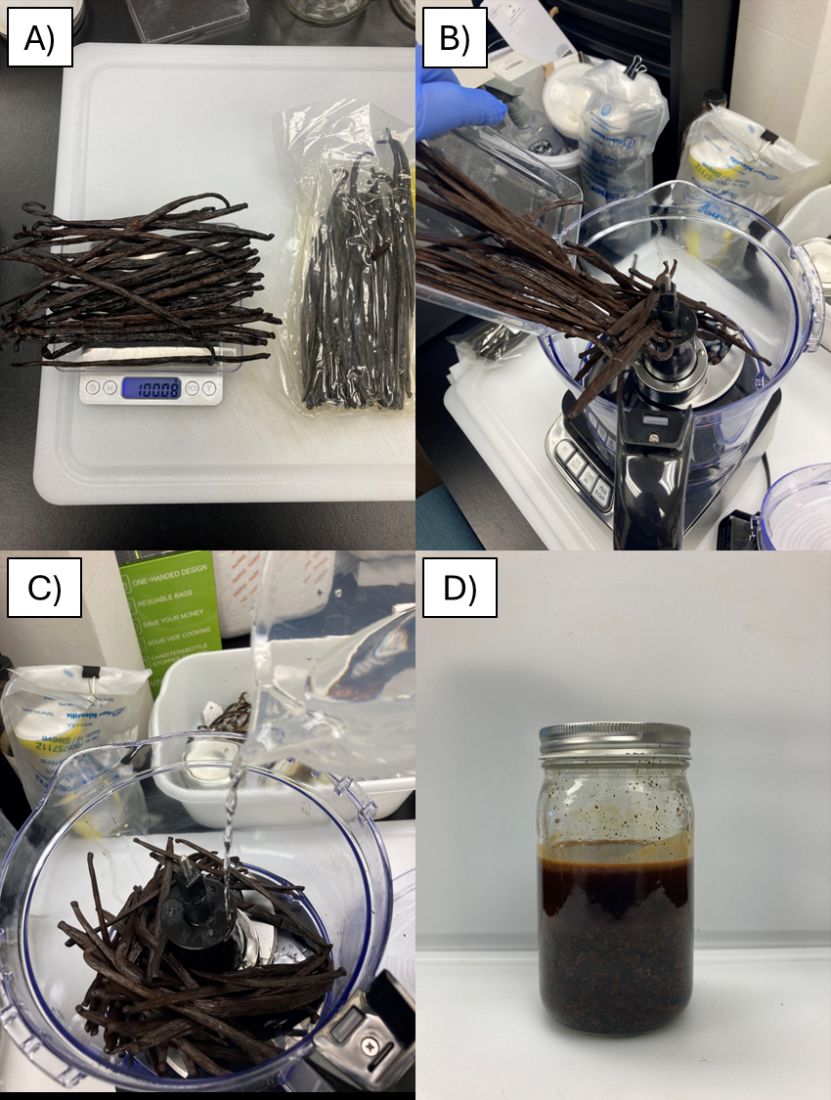

Obtaining vanillin, the primary flavor compound in vanilla extract, is possible through a process called ethanolic maceration. The process of extracting involves grinding up the cured capsules and submerging them in food-grade ethanol. The vanillin, along with other metabolites that contribute to the aroma and flavor profiles, dissolves in the ethanol. Ethanol is the preferred solvent for this process, as it is safe to consume and effective in extracting vanillin (Jadhav et al. 2009). Only food-grade ethanol is recommended for the extraction.

When using the Soxhlet extraction process, a ratio of 1 g of cured vanilla per 100 ml of ethanol is optimal. This process is more efficient at higher temperatures (>78°C). Using a 50% ethanol solution is ideal for vanillin extraction, as the higher polarity enhances vanillin solubility (Jadhav et al. 2009). The solids can be filtered out after two weeks (Figure 4). Alternatively, storing extracts at room temperature in the dark for two weeks can help them obtain satisfactory extraction rates of the desired metabolites.

Credit: Manuel Gastelbondo, UF/IFAS

Alternative and more complex extraction methods include percolation, oleoresin extraction, and supercritical fluid extraction, which offer advantages such as increased yields and purity (Sinha et al. 2008). Enzymatic extraction techniques can also improve vanillin yield by breaking down glucovanillin trapped in cellulose structures (Liaqat et al. 2023).

Use of food grade materials and hygienic conditions are recommended for the process. Methanol and other solvents are not safe for consumption or for use in natural vanilla extract.

References

Arenas, M. A. S., and R. L. Dressler. 2010. “A Revision of the Mexican and Central American Species of Vanilla plumier ex Miller with a Characterization of Their ITS Region of the Nuclear Ribosomal DNA.” Lankesteriana 9 (3): 285–354. https://www.lankesteriana.org/lankesteriana/Vol.9(3)/Lankesteriana%209(3)%20complete%20issue.pdf

Cameron, K. 2011. Vanilla Orchids: Natural History and Cultivation. Timber Press.

de Oliveira, R. T., J. P. da Silva Oliveira, and A. F. Macedo. 2022. “Vanilla beyond Vanilla planifolia and Vanilla x tahitensis: Taxonomy and Historical Notes, Reproductive Biology, and Metabolites. Plants 11 (23): 3311. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11233311

Hänke, H. 2024. 2024 Living Income Reference Price Update for Vanilla Sourced from Madagascar. Fair Trade International. https://www.fairtrade.net/en/get-involved/library/living-income-reference-prices-for-vanilla-from-uganda-and-madag.html

Havkin-Frenkel, D., and F. C. Belanger. 2011. Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology. Blackwell Publishing.

Jadhav, D., B. N. Rekha, P. R. Gogate, and V. K. Rathod. 2009. “Extraction of Vanillin from Vanilla Pods: A Comparison Study of Conventional Soxhlet and Ultrasound Assisted Extraction.” Journal of Food Engineering 93 (4): 421–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.02.007

Liaqat, F., L. Xu, M. I. Khazi, S. Ali, M. U. Rahman, and D. Zhu. 2023. “Extraction, Purification, and Applications of Vanillin: A Review of Recent Advances and Challenges.” Industrial Crops and Products 204 (Part B): 117372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117372

Melbourne, L. 2019. “Edmond Albius: The Boy Who Revolutionised the Vanilla Industry.” The Linnean Society of London, October 16. https://www.linnean.org/news/2019/10/16/edmond-albius

Sinha, A. K., U. K. Sharma, and N. Sharma. 2008. “A Comprehensive Review on Vanilla Flavor: Extraction, Isolation and Quantification of Vanillin and Others Constituents.” International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 59 (4): 299–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687630701539350

Van Dyk, S., P. Holford, P. Subedi, K. Walsh, M. Williams, and W. B. McGlasson. 2014. “Determining the Harvest Maturity of Vanilla Beans.” Scientia Horticulturae 168: 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.02.002