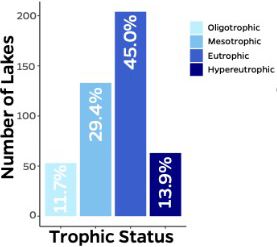

Lakes are diverse and come in all shapes and sizes. So, how do scientists describe and organize what we know about the millions of waterbodies across the world? The Trophic State Classification System is one of the more commonly used systems, including by the by Florida LAKEWATCH Program.

Using this system, waterbodies can be grouped into one of four categories, called “trophic states,” based on their level of biological productivity. Understanding the four trophic states can help you understand how your waterbody compares to others. You can also better understand what changes in its water quality over time could mean. This publication is intended for lake managers and anyone interested in waterbodies and waterbody monitoring and management. By reading this handout, you can learn:

- how to use water chemistry and clarity to determine a waterbody’s trophic state

- what criteria to use to define the four trophic states

- which trophic state category your waterbody fits into

- how you can use the Trophic State Classification System to learn about your lake

What’s in a Name?

The names of the four trophic states, from the lowest level (top) of biological productivity to the highest (bottom), are listed below:

- Oligotrophic (oh-lig-oh-TROH-fic)

- Mesotrophic (mes-oh-TROH-fic)

- Eutrophic (you-TROH-fic)

- Hypereutrophic (hi-per-you-TROH-fic)

The root word trophic originates from the Greek word trophikos, meaning “of or relating to nutrition.” The prefixes used in the trophic state terminology (i.e., the above words) also provide clues to their meaning.

- Oligo means “scant or lacking.”

- Meso means “mid-range.”

- Eu means “good or sufficient.”

- Hyper means “over abundant”

There are also lakes that are classified as “ultra-oligotrophic.” These lakes have very low concentrations of nutrients. Florida has few, if any, such ecosystems. Most ultra-oligotrophic lakes are in polar regions.

Credit: Florida LAKEWATCH 2024

Using Water Chemistry to Determine a Waterbody’s Trophic State

It’s no coincidence that the UF/IFAS Florida LAKEWATCH program monitors the same four water chemistry parameters that scientists use to determine a waterbody’s trophic state: total chlorophyll, total phosphorus, total nitrogen, and water clarity. These four parameters serve as core indicators of a waterbody’s biological productivity, which is a lake’s ability to support plant and animal life. Let’s take a closer look at what each of these parameters tells us!

Chlorophyll is the dominant green pigment found in most algae (the microscopic plant-like organisms living in a waterbody). Chlorophyll enables photosynthesis, which is how algae use sunlight to make energy. In fact, most algae are so dependent upon chlorophyll pigments for survival that a measurement of the concentration of all the chlorophyll pigments found in a water sample (called total chlorophyll) can be used to estimate the amount of free-floating algae in that waterbody. When large amounts of total chlorophyll are found in a sample, it generally means a lot of algae is present in the waterbody it came from.

Once we have an estimate of the amount of algae in a waterbody, we can estimate its trophic state. Because algae are a basic food source for many aquatic animals, their abundance is a crucial factor in how much life a waterbody can sustain. In general, when measurements of total chlorophyll are high (indicating lots of algae are present), the waterbody will be more biologically productive.

Phosphorus is a nutrient necessary for the growth of algae and aquatic plants. It is found in many forms in waterbody sediments and dissolved in the water. UF/IFAS Florida LAKEWATCH uses a measurement called “total phosphorus” which includes all the various forms of phosphorus in a sample.

When phosphorus concentration is low (even if all other factors necessary for plant and algae growth are present in sufficient amounts), low biological productivity is usually expected. Conversely, highly productive waterbodies usually have relatively high concentrations of phosphorus.

In waterbodies where phosphorus concentrations are low enough to prevent aquatic plants and algae from growing, scientists say phosphorus is the “limiting nutrient.”

Nitrogen is also a nutrient necessary for the growth of algae and aquatic plants. As for phosphorus, the Florida LAKEWATCH measurement of nitrogen includes the sum of all forms of nitrogen, called “total nitrogen.” When total nitrogen is present in low concentration (and, again, other factors necessary for plant and algae growth are present in sufficient amounts), lower biological productivity can be expected. Thus, like phosphorus, nitrogen can be a limiting nutrient.

Water clarity refers to the clearness or transparency of water. Water clarity is determined by using an 8-inch diameter disk, called a Secchi (pronounced SEK-ee) disk. The maximum depth at which the Secchi disk can be seen when lowered into the water is measured. Several factors reduce water clarity in the following ways:

- Free-floating algae in the water make waterbodies less clear;

- Dissolved organic compounds, like tannins, cause waterbodies to appear reddish or brown, i.e., tea-colored and less clear; and

- Suspended solids (tiny particles stirred up from the lake bottom or washed in from the watershed) can cause the water to be less clear.

Aquatic plants, or macrophytes, also play a major role in a waterbody’s biological productivity. This occurs through their photosynthesis and by providing habitat for aquatic organisms and supporting attached microorganisms like algae and small animals. Aquatic plant abundance also serves as an important indicator of a waterbody’s trophic state. Consequently, some waterbodies may be classified into the wrong trophic state if the abundance of aquatic plants is not considered. For example, when submersed aquatic vegetation covers more than 50% of a lake’s bottom, there will generally be less algae floating in the water*. The resulting low chlorophyll measurements may cause some waterbody managers to classify a lake as having low biological productivity, even though the abundant submersed aquatic plants demonstrate its high productivity. Thus, knowing what aquatic plants are in your lake is important for understanding its trophic state.

*One explanation for the lack of algae is that the submersed plants, or the algae attached to them, use the available phosphorus, depriving free-floating algae of this nutrient. Another is that the submersed plants anchor nutrient-rich sediments to the bottom, preventing disturbance by wind, waves, or humans, thus limiting phosphorus availability to free-floating algae.

Lake Trophic State Criteria

There are several trophic state classification systems being used today. In 1980, two scientists, Forsberg and Ryding, developed criteria for classifying lakes into trophic state categories based on four water chemistry parameters (total chlorophyll, total phosphorus, total nitrogen, and water clarity). Although developed for Swedish lakes, their criteria work well for lakes in Florida and have been adopted by UF/IFAS Florida LAKEWATCH. Definitions of the four trophic states (including Forsberg and Ryding’s criteria for classification) and some common features of waterbodies falling under each type are listed below:

The Four Trophic States

Oligotrophic

Clear water and a sandy bottom. Few aquatic plants and few fish. Wildlife may be sparse.

Criteria: Chlorophyll less than 3 micrograms per liter; total phosphorus less than 15 micrograms per liter; total nitrogen less than 400 micrograms per liter; water clarity, Secchi disk visibility more than 13 feet down.

A good lake for swimming and water skiing.

Mesotrophic

Moderately clear water and a layer of sediment on the lake floor. Moderate populations of aquatic plants and fish.

Criteria: Chlorophyll 3–7 micrograms per liter; total phosphorus 15–25 micrograms per liter; total nitrogen 400–600 micrograms per liter; water clarity, Secchi disk visibility from 8–13 feet down.

A good lake for sailing, canoeing, kayaking, or just relaxing on a floatie.

Eutrophic

Lower clarity water with potentially abundant fish and wildlife. May have an abundance of aquatic plants Increased organic sediment on the bottom.

Criteria: Chlorophyll 7–40 micrograms per liter; total phosphorus 25–100 micrograms per liter; total nitrogen 600–1500 micrograms per liter; water clarity, clear visibility from 3–8 feet down.

A good lake for fishing and watching for wading birds and other wildlife.

Hypereutrophic

Hypereutrophic lake water may be similar in clarity to eutrophic lake water with many plants, or it may be exceedingly murky with sparse plants. Very thick sediment on the lake bottom and abundant fish and wildlife.

Criteria: Chlorophyll more than 40 micrograms per liter; total phosphorus more than 100 micrograms per liter; total nitrogen more than 1500 micrograms per liter; water clarity, clear visibility less than 3 feet down.

A good lake for fishing and watching for wading birds and other wildlife.

Credit: UF/IFAS

How Trophic States can be Useful to You

You can monitor to see if your waterbody’s trophic state changes over time. Many people are concerned about the impact of activities on their waterbody including increasing population, nearby mining, drought, flooding, agriculture, or other factors. However, small changes in water quality and ecology may be normal in living systems like waterbodies.

You can make better-Informed decisions about lake changes: are they merely small natural fluctuations or are they signs of a bigger issue? Although the answer to this question is not simple, many aquatic scientists view changes that cause a waterbody to shift from one trophic state to another to be meaningful. This is because of the impact on biological productivity, which in-turn impacts important activities like fishing and boating, as well as wildlife habitats for valued wildlife such as herons, otters, and alligators. Thus, the trophic state classification provides a useful yardstick for evaluating the seriousness of changes in your waterbody.

You can communicate more effectively with your neighbors and water management professionals. Using the trophic state vocabulary enables us to describe a waterbody and its biological productivity in a single word. For example, to say a waterbody is oligotrophic should evoke a picture of clear water, few aquatic plants, a sandy bottom, few fish, and scarce wildlife. Although some professionals debate the specifics, these descriptions are accurate enough to be extremely useful in water management communication.

You can reconcile your expectations for lake-related activities with a waterbody’s natural potential. For example, oligotrophic waterbodies are often considered better suited for swimming because they typically have low concentrations of algae and clearer water. On the other hand, eutrophic or hypereutrophic waterbodies are often better suited for fishing and bird watching because they typically have an abundance of food and habitat for wildlife. Most swimmers, however, would not enjoy being in the less clear water or the abundant plant growth that is generally characteristic of these highly productive waterbodies.

Credit: Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS

Anthropogenic Eutrophication

Eutrophication is the process of a waterbody increasing in biological productivity. This process can occur naturally depending on changes in the lake drainage basin. Human activities, however, can cause rapid eutrophication, sometimes causing shifts in trophic status over decades instead of centuries. We refer to this as anthropogenic or cultural eutrophication. Repeated and excessive application of fertilizer to lawns, agricultural lands, and golf courses, for example, can lead to anthropogenic eutrophication because fertilizers contain limiting nutrients (i.e., phosphorus and nitrogen). Anything that enhances rainwater runoff increases the amount of nutrients reaching lakes. For example, paving roads or walkways can increases runoff by increasing the amount of impervious surfaces, and deforestation may increase runoff and cause greater erosion. Septic tanks can also contribute to nutrient pollution, especially in Florida where sandy soils are less effective at filtering out nutrients before they reach groundwater and nearby waterbodies. You can help combat the effects of anthropogenic eutrophication by following fertilizer label directions and obeying local ordinances for fertilizing, as well as by planting native species along lake shorelines. (Native plants along a lakeshore help by intercepting nutrients before they can reach the lake.) UF/IFAS Extension’s Florida Friendly LandscapingTM Program is a great resource for finding good plant options to use.

Resources

Florida LAKEWATCH website https://lakewatch.ifas.ufl.edu/

UF/IFAS’s Florida Friendly LandscapingTM website https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/