The state of Florida has 17.16 million acres (26,807 square miles) of forestland, representing 50 percent of the state's total land area. The state has extensive natural and planted pine and hardwood forests that are used commercially for the production of a wide variety of wood building materials, consumer paper and packaging products, chemicals, and renewable biomass fuels. About 44 percent of forestlands are comprised of slash, loblolly, and longleaf pines, while 47 percent are hardwood or mixed hardwood and pine, and 9 percent are tropical hardwoods and other species. Nearly two-thirds (66%) of Florida's forestlands are privately owned by industry, corporations, families, or individuals, while 17 percent are state owned, 16 percent are owned by the federal government, and 3 percent are owned by county and municipal governments. About 16 million tons of softwood and hardwood pulpwood and sawtimber, valued at around $315 million, is harvested annually from Florida forests. An average of 74 million trees are planted annually on 122,000 acres of forest land. Annual forest growth is 1.92 times the harvest volume, indicating that current harvest levels are sustainable. The state has 1,843 employer business establishments in the forest industry, including 74 primary wood-using mills and 363 secondary wood and paper product manufacturers. In 2016, over 3 million metric tons of forest products, valued at $1.801 billion, were exported to international destinations from Florida ports.

Total economic contributions of the forest industry were estimated using data on direct employment in 32 industry sectors for forestry production (timber tracts, logging, forestry support activities), primary wood products manufacturing (sawmills, wood preservation, plywood/veneer, engineered wood, reconstituted wood, other), secondary wood products manufacturing (cut stock, millwork, wood containers, windows/doors, pallets), primary paper products manufacturing (pulp, paper, paperboard mills), converted paper products manufacturing (paperboard containers, bags, stationery, sanitary tissue, towels), forest chemical products manufacturing (turpentine, rosin, tall oil fatty acids, fragrances and flavorings), allied manufacturing of sawmill/woodworking/paper machinery, wholesale trade in lumber and wood products (lumber and wood brokers, distributors), and biomass electric power generation. Total economic contributions associated with forest-based recreation activities were estimated using data on recreational spending by nonresident visitors to Florida's 3 National Forests, 37 State Forests, and 54 Wildlife Management Areas.

A regional economic model (IMPLAN) was used to estimate the total economic contributions of the forest industry and forest-based recreation on the Florida economy, including industry supply chain activity (indirect effects) and re-spending of income by households and governments (induced effects). In 2016, the forest industry sectors directly employed 36,055 persons (full-time and part-time jobs) and collected $12.55 billion in industry revenues. Total economic contributions of the Florida forest industry in 2016 are summarized in Table 1. For all forest industry groups, total economic contributions included 124,104 full-time and part-time jobs, $25.05 billion in industry output or revenues, $10.96 billion in value added (Gross State Product), $6.58 billion in labor income (employee wages, salaries, benefits, business owner income), $880 million in state and local government tax revenues, and $1.72 billion in federal government tax revenues. The largest forest industry groups in terms of employment contributions were primary and converted paper product manufacturing (37,355 and 20,615 jobs, respectively), together representing 47 percent of total industry contributions, followed by primary wood product manufacturing (18,549 jobs), forestry production (16,594 jobs), wholesale trade in lumber and wood (14,255 jobs), forest chemicals manufacturing (9,178 jobs), and secondary wood product manufacturing (7,101 jobs). Total output contributions of the Florida forest industry estimated are similar to the estimates for the environmental horticulture industry (nursery/greenhouse production, landscape services, retail garden centers) (Hodges et al. 2016) and are significantly larger than for the iconic Florida citrus industry in 2015–16 (Court et al. 2017).

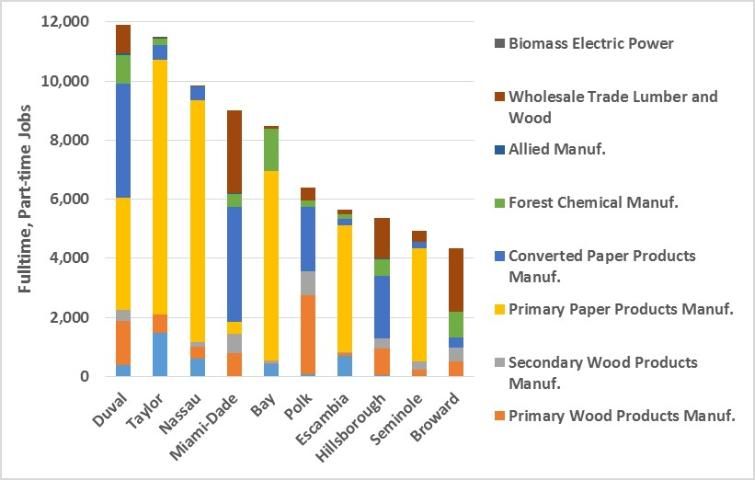

The top ten Florida counties in terms of forest industry direct output (sales revenues) were Duval ($1.37 billion), Miami-Dade ($1.18 billion), Taylor ($877 million), Polk ($811 million), Nassau ($773 million), Bay ($723 million), Hillsborough ($707 million), Putnam ($604 million), Broward ($502 million), and Escambia ($437 million). The top ten counties in terms of employment contributions were Duval (11,885 jobs), Taylor (11,456), Nassau (9,847), Miami-Dade (9,010), Bay (8,461), Polk (6,399), Escambia (5,653), Hillsborough (5,370), Seminole (4,943), and Broward (4,334), as shown in Figure 1. The mix of forest industry sectors is quite different across Florida counties: Taylor, Nassau, Bay, Escambia, and Seminole Counties are dominated by primary paper products manufacturing due to the presence of pulp and paper mills: Duval, Miami-Dade, Polk, Hillsborough, and Putnam Counties have major converted paper products manufacturing; Polk, Duval, Hillsborough, Taylor, and Miami-Dade Counties have significant wood products manufacturing; Duval and Bay Counties have significant forest chemical (allied) manufacturing; the urbanized Counties of Miami-Dade, Hillsborough, Duval, Polk, and Seminole have significant wholesale trade activity (Figure 1).

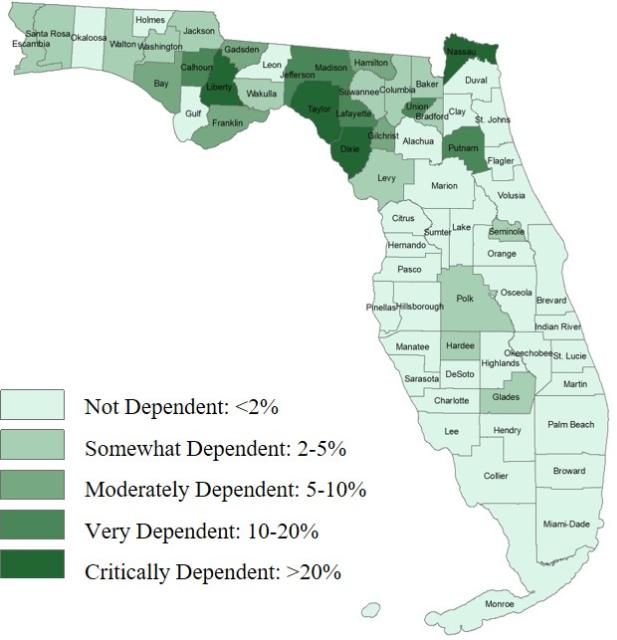

Employment contributions of the Florida forest industry represented 1.10 percent of the state workforce and total value-added contributions represented 1.23 percent of Gross State Product (GSP), indicating the relative importance of this industry to the state of Florida. Community dependence on the forest industry was analyzed in terms of the share of total employment or value added (GSP) in each county: four counties were classified as "critically dependent," with employment contributions representing over 20 percent of the county workforce and value-added contributions over 30 percent of GSP (Taylor, Liberty, Nassau, and Dixie); seven counties were classified as "very dependent," with over 10 percent of employment or 15 percent of GSP (Putnam, Jefferson, Union, Lafayette, Madison, and Calhoun), and five counties were considered "moderately dependent," with employment contributions over five percent (Gilchrist, Hamilton, Bay, Franklin, and Gadsden), as shown in Figure 2. Although timber production and dependence on the forest industry was highest in rural counties, the overall economic contributions of the forest industry were greatest in metropolitan area counties with populations of 250,000 or more and in counties adjacent to metro areas, demonstrating the important forestry-related linkages that exist between urban and rural areas throughout the state.

In addition to industrial forest-related activity, public forestlands in Florida support a variety of recreational activities and attract a significant number of recreational visitors. National Forests, State Forests, and Wildlife Management Areas in Florida cover a total of 3.70 million acres and received a total of 6.93 million visitor-days in 2015. Total economic contributions of forest-based recreational spending by nonresident visitors to these areas were estimated at 7,818 jobs, $851 M in industry output, $505 M in value added, $48 M in state and local tax revenues, and $80 M in federal tax revenues (Table 1).

Florida forests also provide many non-marketed environmental or ecosystem services such as surface and groundwater storage, air and water purification, atmospheric carbon storage, mitigation of droughts and floods, stabilization of climate and moderation of extreme weather events, generation and preservation of soils, detoxification and decomposition of wastes, cycling and movement of nutrients, control of agricultural pests, provision of wildlife habitat, and maintenance of biodiversity. Although these ecosystem services were not explicitly quantified, secondary sources were compiled that suggest a value of approximately $24 to $32 billion annually.

References

Court, C.D., A.W. Hodges, M. Rahmani and T. H. Spreen. Economic Contributions of the Florida Citrus Industry in 2015-16. Sponsored project report to the Florida Department of Citrus, University of Florida, Food and Resource Economics Department, Gainesville, 35 pages, May 9, 2017, available at http://fred.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/economic-impact-analysis/Economic_Impacts_of_the_Florida_Citrus_Industry_2015_16.pdf

Hodges, A.W., H. Khachatryan, M. Rahmani and C.D. Court. Economic Contributions of the Environmental Horticulture Industry in Florida in 2015. Sponsored project report to Florida Nursery Growers and Landscape Association. University of Florida, Food and Resource Economics Department, Gainesville, 57 pages, Nov. 22, 2016, available at http://fred.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/EconContEnvirHortIndFL2015-11-15-16.pdf