Introduction

Credit: Raychel Rabon, UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants

Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) is an invasive, submerged aquatic plant that poses a significant threat to Florida’s freshwater ecosystems (Enloe et al. 2019). Introduced into Florida's waterways during the 1950s through the aquarium plant trade, it swiftly proliferated throughout the state. Hydrilla fragments spread easily among waterbodies through boat trailers and wildlife (Gettys and Enloe 2019). Today, the transportation, importation, cultivation, or sale of hydrilla is strictly prohibited. It is classified as a Florida Class 1 Prohibited Aquatic Plant and is listed on the Federal Noxious Weeds list (USDA NRCS 2015). Since its introduction in the 1950s, hydrilla has posed an environmental threat to Florida's lakes, rivers, reservoirs, ponds, and canals. This invader alters crucial water quality parameters, affecting oxygen levels, temperature, and pH, while also obstructing sunlight, thereby disrupting aquatic ecosystems (Enloe et al. 2019). Beyond its environmental impact, hydrilla severely hampers recreational activities, disrupting Florida's vital tourism industry (Enloe et al. 2019). These disruptions include limitations on boating and swimming, as well as the proliferation of mosquitoes and a reduction in biodiversity, rendering these areas less appealing for visitors (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 2022). It is essential to manage hydrilla due to these negative effects. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) is responsible for managing hydrilla in Florida under its Aquatic Plant Management Program. Between 2005 and 2015, $66 million was spent on hydrilla management in Florida, which accounts for more than half of the total federal and state public funds allocated to aquatic plant management in Florida during that period (Gettys and Enloe 2019). Currently, it is estimated that $15 million is spent annually on hydrilla management by the state of Florida (Weber et al. 2021).

In this publication, we present an overview of stakeholder concerns regarding hydrilla management, synthesizing insights gathered from the largest state-wide survey of Florida residents about invasive aquatic plant management in the state’s public waters. Our objective is to equip decision-makers, including agencies like FWC, with valuable insights. By understanding stakeholder concerns, decision-makers can formulate aquatic invasive species management policies that are effective and that garner public support.

Management Practices

Hydrilla is primarily managed with aquatic herbicides, a chemical control method that must be approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) before it is used (Enloe et al. 2019). The most common herbicides used to control hydrilla in Florida are endothall, fluridone, and florpyrauxifen-benzyl. Aquatic herbicides can be applied via aircraft, boats (Figure 2), trucks, or backpack sprayers depending on the target area (Enloe et al. 2019).

Credit: UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants

Credit: James Leary, UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants

Other hydrilla management methods exist, such as mechanical harvesting (Figure 3), in which hydrilla is cut and removed from bodies of water. Mechanical harvesting boats are equipped with paddle wheels, articulated cutters, and conveyor tables that can harvest hydrilla to be disposed of offshore (Enloe et al. 2019). Mechanical harvesting is used in Florida, but to a much lesser extent than herbicides. Studies suggest that it requires 5–9 harvester-hours each year to manage a single acre of hydrilla and its regrowth (Leary 2020). Given the widespread infestation of hydrilla in the state, mechanical harvesting is financially prohibitive. To illustrate, consider Lake Tohopekaliga, where dealing with 3,500 acres of hydrilla, approximately 40% of the total infested area, would necessitate an annual commitment of 17,000–30,000 harvester-hours (Leary 2020).

There are advantages and disadvantages to chemical and mechanical control methods. Aquatic herbicides are currently the most commonly used management method due to their cost, safety, and efficacy.

Advantages and disadvantages of control methods:

Aquatic Herbicides

Advantages

- Kills or inhibits the growth of the plant

- Cost-effective

- Many herbicides allow for selectivity

Disadvantages

- Dead plant material decomposes in the water and releases nutrients

- Some herbicides have water use restrictions after application

- Plant death may be slow

Mechanical Harvesting

Advantages

- Biomass is removed and does not decompose in the waterbody

- Achieves immediate control, since the plants are removed

Disadvantages

- Boats are slow moving and may not be able to keep pace with regrowth

- More expensive than herbicides

- Not selective; animals and other plants may be harvested as well as the target plant

Management in Practice

The state of Florida has struggled to manage hydrilla due to stakeholder concerns about the potential environmental impacts of herbicide use in Florida waters. Understanding how stakeholders perceive invasive species management is important because public support plays a pivotal role in successful implementation of invasive aquatic management practices. For example, in 2019, FWC had to enact a three-month statewide moratorium on the use of aquatic herbicide. This decision was prompted by expressed public concerns regarding the potential adverse effects of herbicides on water quality. Management of hydrilla is further complicated with conflicting stakeholder interests that aquatic plant managers must take into consideration. For example, anglers and duck hunters often prefer substantial hydrilla cover due to perceived benefits for fish and wildlife habitat, while homeowners or those who use the lake for other recreational purposes generally prefer less hydrilla cover.

Survey Design

From September–October 2022, we used a Qualtrics panel to conduct a state-wide online survey of 3,069 Florida residents and gather information on awareness and preferences for hydrilla management in the state. To participate in our survey, respondents had to be at least 18 years old and be a resident of Florida. Respondents were first asked to rate their awareness of hydrilla. Next, they provided information about their history of visiting Florida’s public lakes and answered questions regarding their satisfaction with hydrilla management. They also shared their level of concern regarding the prevalence of hydrilla on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 indicating “not concerned” and 5 indicating “very concerned.” In terms of our analysis, “concern” is defined as worry over the subject of the question. Respondents were also asked to express their perspectives on the use of aquatic herbicides and mechanical harvesting for hydrilla control using the same Likert scale listed previously. If respondents indicated they were at least somewhat concerned over hydrilla management practices, they were then prompted to indicate which factors they were most concerned about regarding the use of aquatic herbicides and mechanical harvesting (see Table 1).

Table 1. Respondent concern options by control measure.

Results

Respondent Demographics

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents.

Familiarity with Hydrilla

Respondents were asked whether they were familiar with hydrilla and its management practices. Prior familiarity with hydrilla and its methods of control can potentially influence public perceptions and concerns regarding hydrilla prevalence and management. Of the 3,069 survey participants, more than half (53%) were familiar with hydrilla, but less than a fourth (22%) were familiar with hydrilla management practices, implying a general lack of awareness amongst the population about how this invasive aquatic plant is controlled. Of those who were not previously familiar with hydrilla management, 55% were at least somewhat concerned over the use of aquatic herbicides as a control method and 45% were at least somewhat concerned over the use of mechanical harvesting. Of those who were familiar with hydrilla management, only 19% and 13% were at least somewhat concerned over the use of aquatic herbicides and mechanical harvesting, respectively. This result suggests that knowledge of hydrilla management practices is associated with lower levels of concern over control measures.

Stakeholder Perceptions

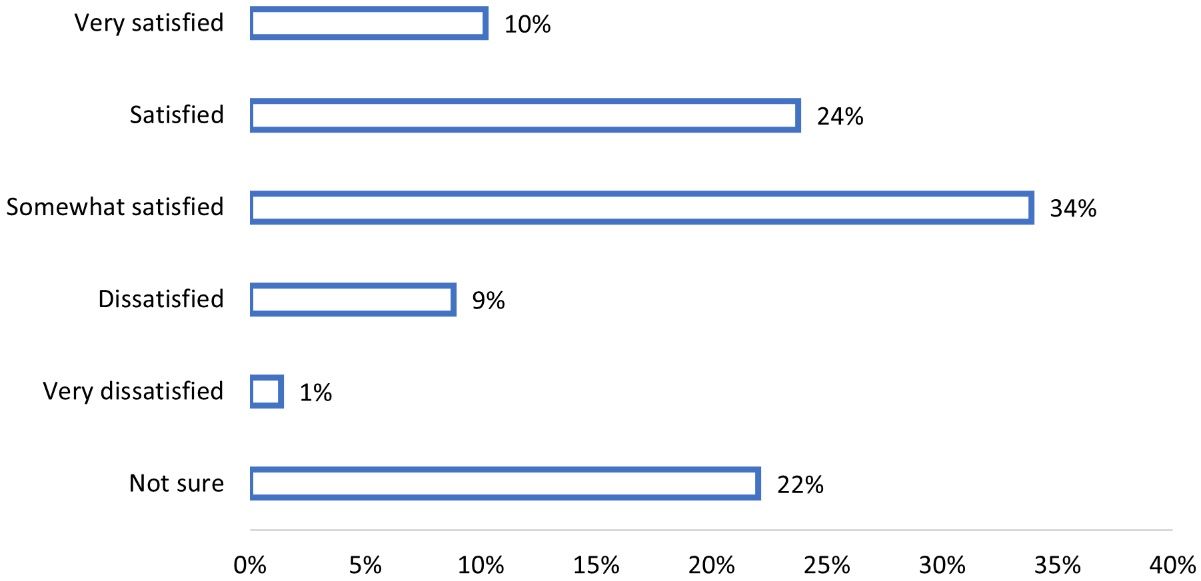

Our survey aimed to explore the views of various stakeholder groups, recognizing that their classifications may influence their perceptions of hydrilla management. Stakeholder categories in this survey included waterfront property owners, boat owners, individuals with fishing licenses or waterfowl permits, individuals whose livelihoods depended on freshwater activities (e.g., fishing tournaments, airboat tours, etc.), and those who had visited a freshwater lake. The most prominent stakeholder group was freshwater lake visitors, comprising over 65% of respondents, 59% of which had visited a lake at least once in the last 12 months and 46% of which had visited a lake at least once in the past 3 months. This is followed by fishermen (30%), and boat owners, waterfront property owners, and waterfowl permit holders, each accounting for between 10% to 15% of our respondents (note that these categories overlap). The overall satisfaction with hydrilla management is broken down in Figure 4, where 68% of respondents were at least somewhat satisfied with the current state of hydrilla management in Florida lakes.

Credit:

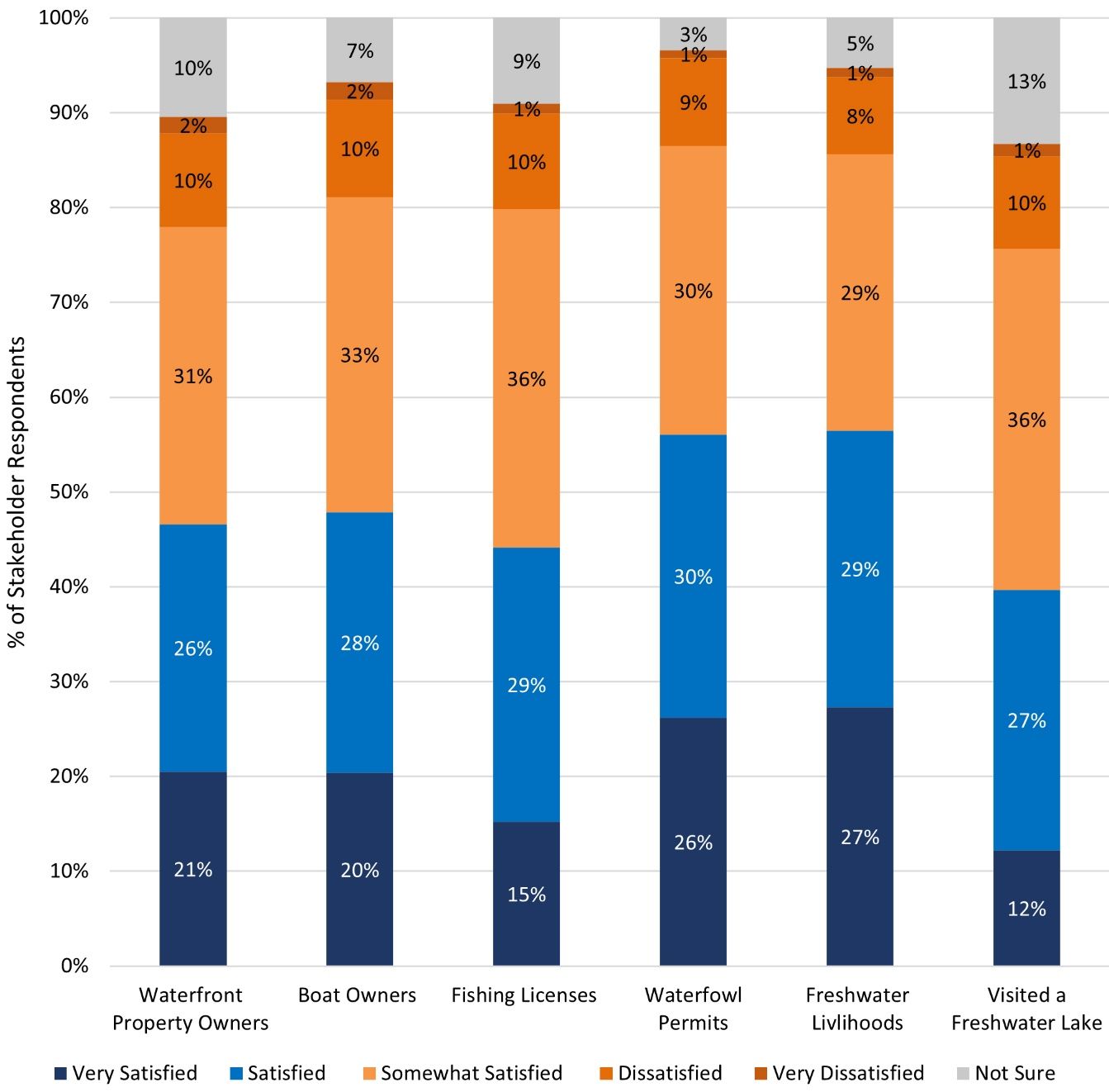

Breaking this information down into specific stakeholder groups, over three quarters of respondents from every defined stakeholder group were at least somewhat satisfied with hydrilla management. Among all stakeholder groups, those holding waterfowl permits expressed the highest levels of satisfaction with current hydrilla management in the state, whereas those who had previously visited a freshwater lake were the least satisfied (Figure 5).

Credit:

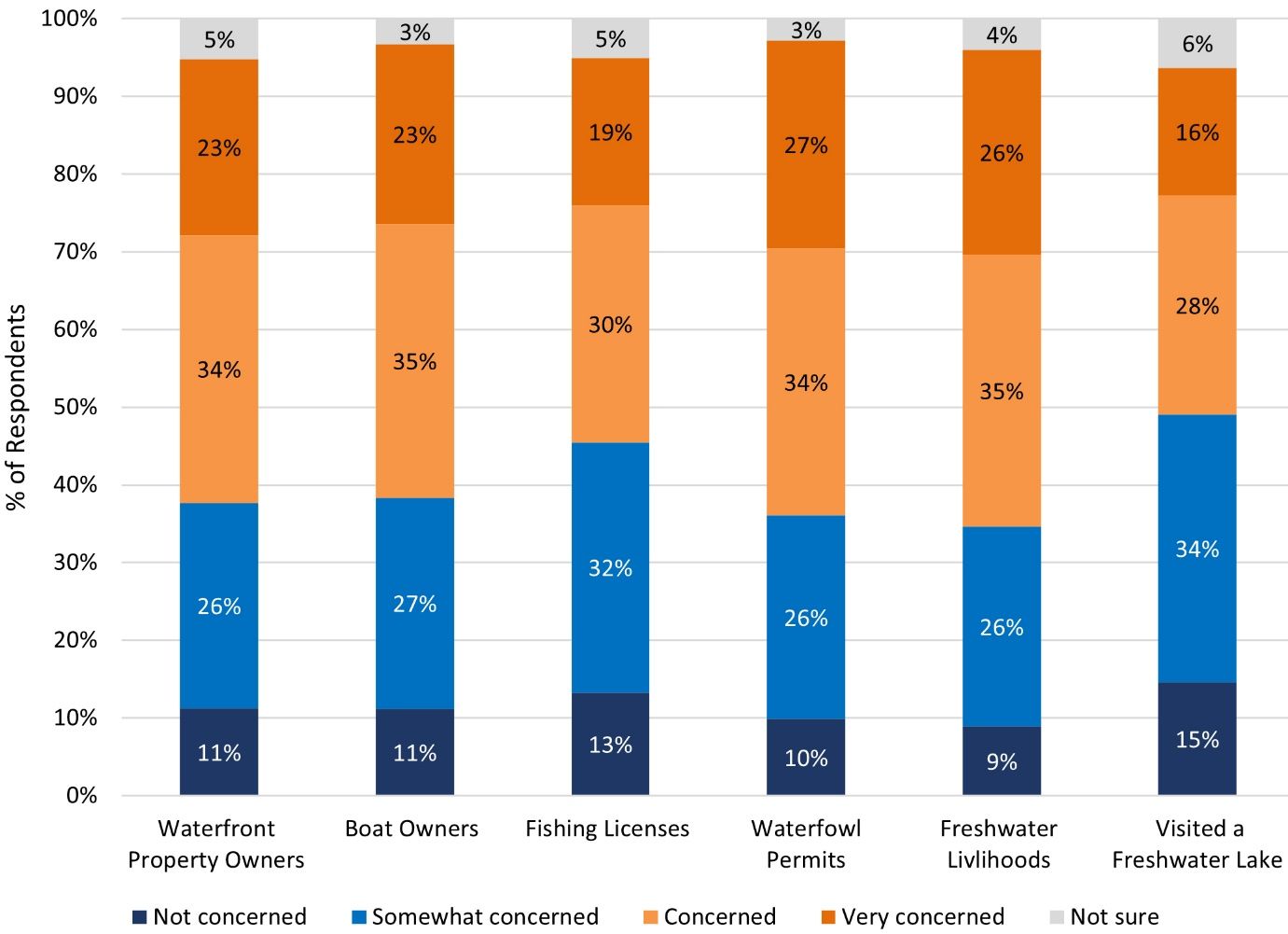

However, our data also shows that Florida residents have concerns about the methods used to manage hydrilla in the state. The breakdown of stakeholder concerns for each management option is presented in Figures 6 and 7. Stakeholders with waterfowl permits and those individuals whose livelihoods depend on freshwater activities expressed the strongest concerns about the use of aquatic herbicides, with over 60% of stakeholders in each group indicating that they are either concerned or very concerned about herbicide use to manage hydrilla. This was followed by boat owners (58%) and waterfront property owners (57%).

Credit:

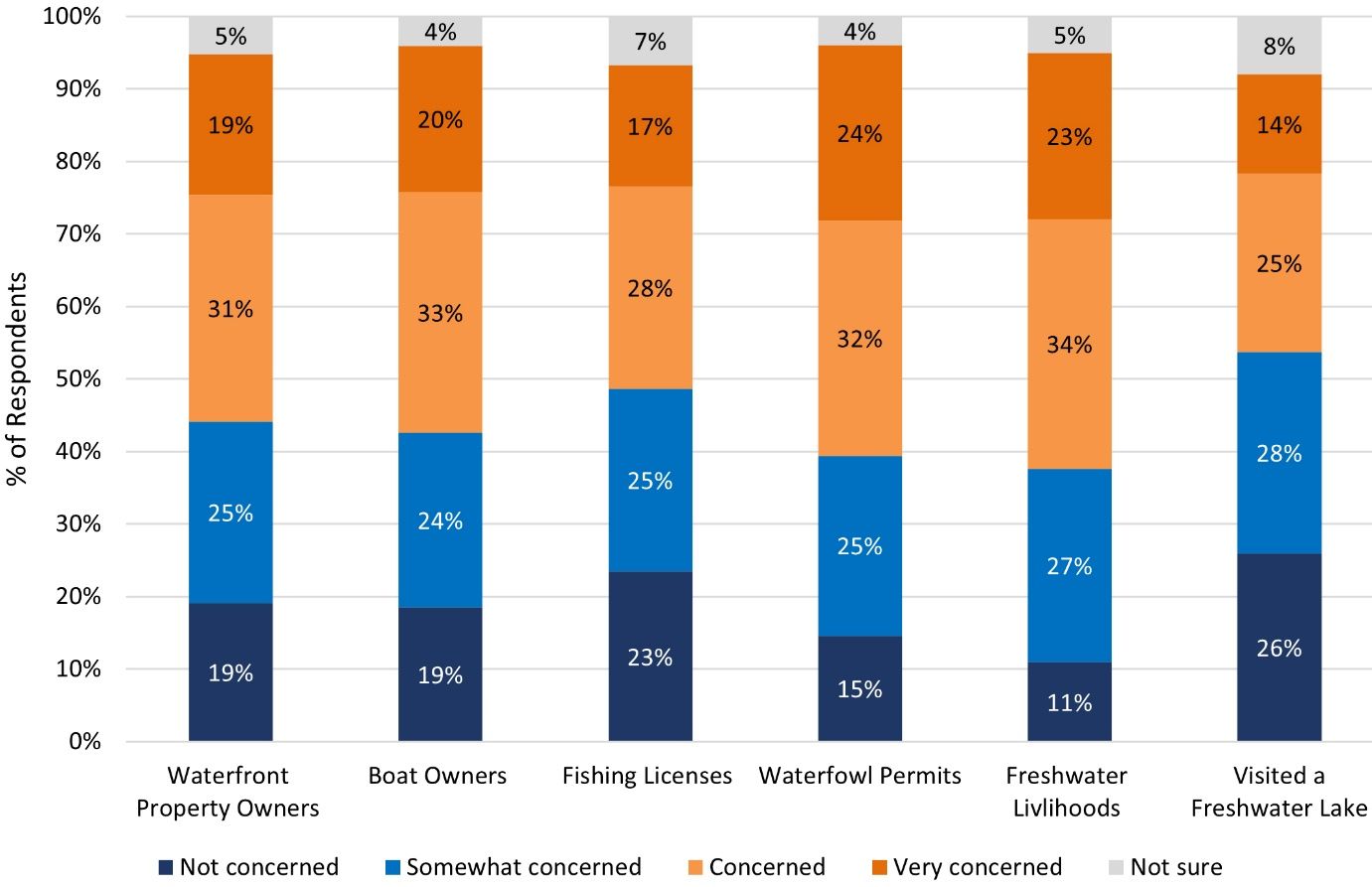

When it comes to mechanical harvesting, respondents in all stakeholder categories indicated some level of concern for the use of this control method. However, those whose livelihoods depend on freshwater activities were the most concerned, with 57% of respondents in this group reporting that they were either concerned or very concerned (Figure 7).

Credit:

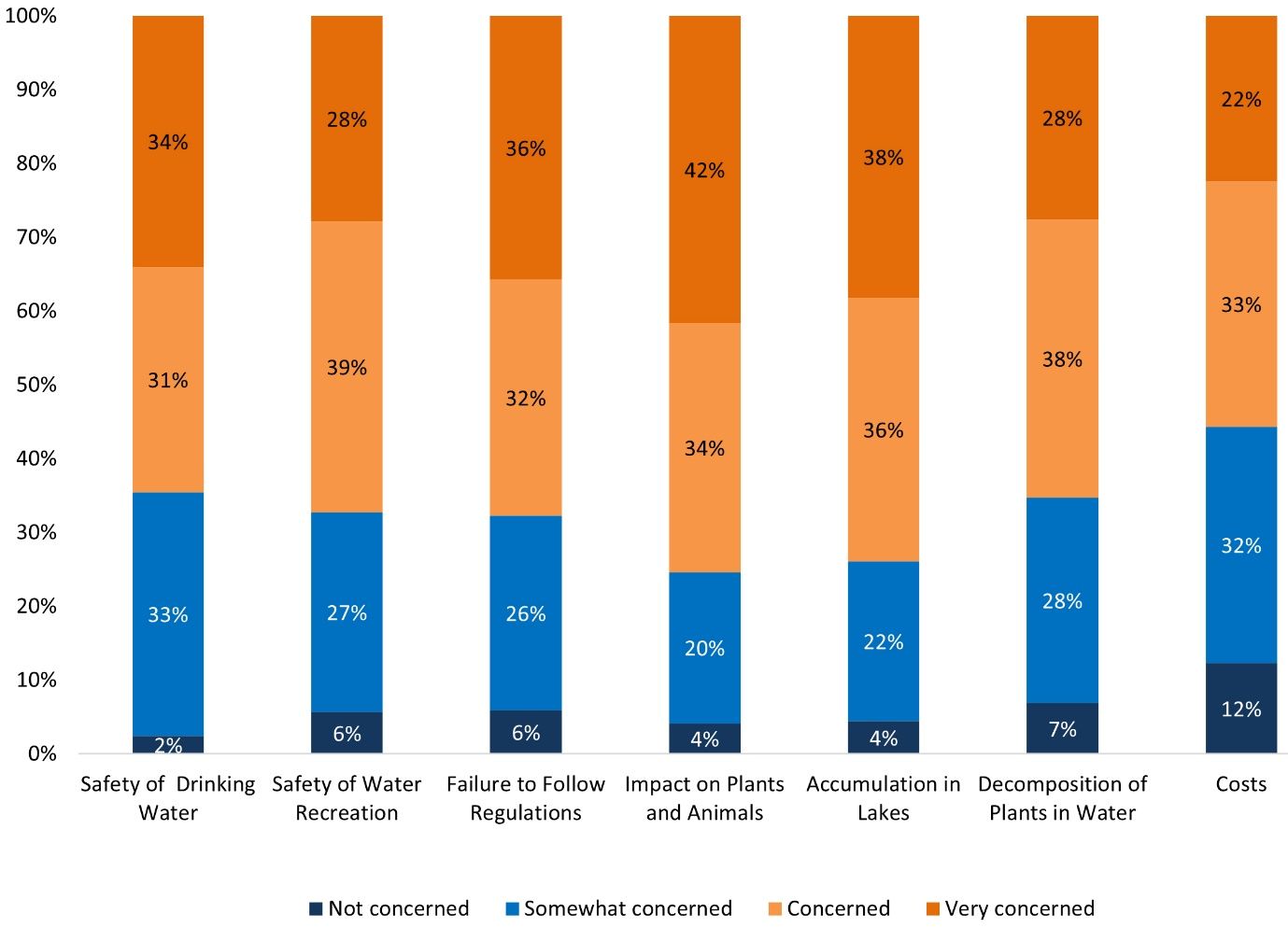

We asked respondents to indicate which specific characteristics of both hydrilla control methods were most concerning to them. These results are presented in Figures 8 and 9. Among the characteristics, respondents were most concerned over the impact of herbicides on the safety of drinking water, harmful impacts to plants and animals, and accumulation of herbicides in the water. This result further implies a lack of awareness regarding hydrilla control measures, and invasive aquatic species management at large, as recent research has found that aquatic herbicides do not build up in lake sediment (Hoyer et al. 2022). Furthermore, our analysis reveals that more than half of the respondents stated that they were very concerned or concerned about the cost of applying herbicides (Figure 8).

Credit:

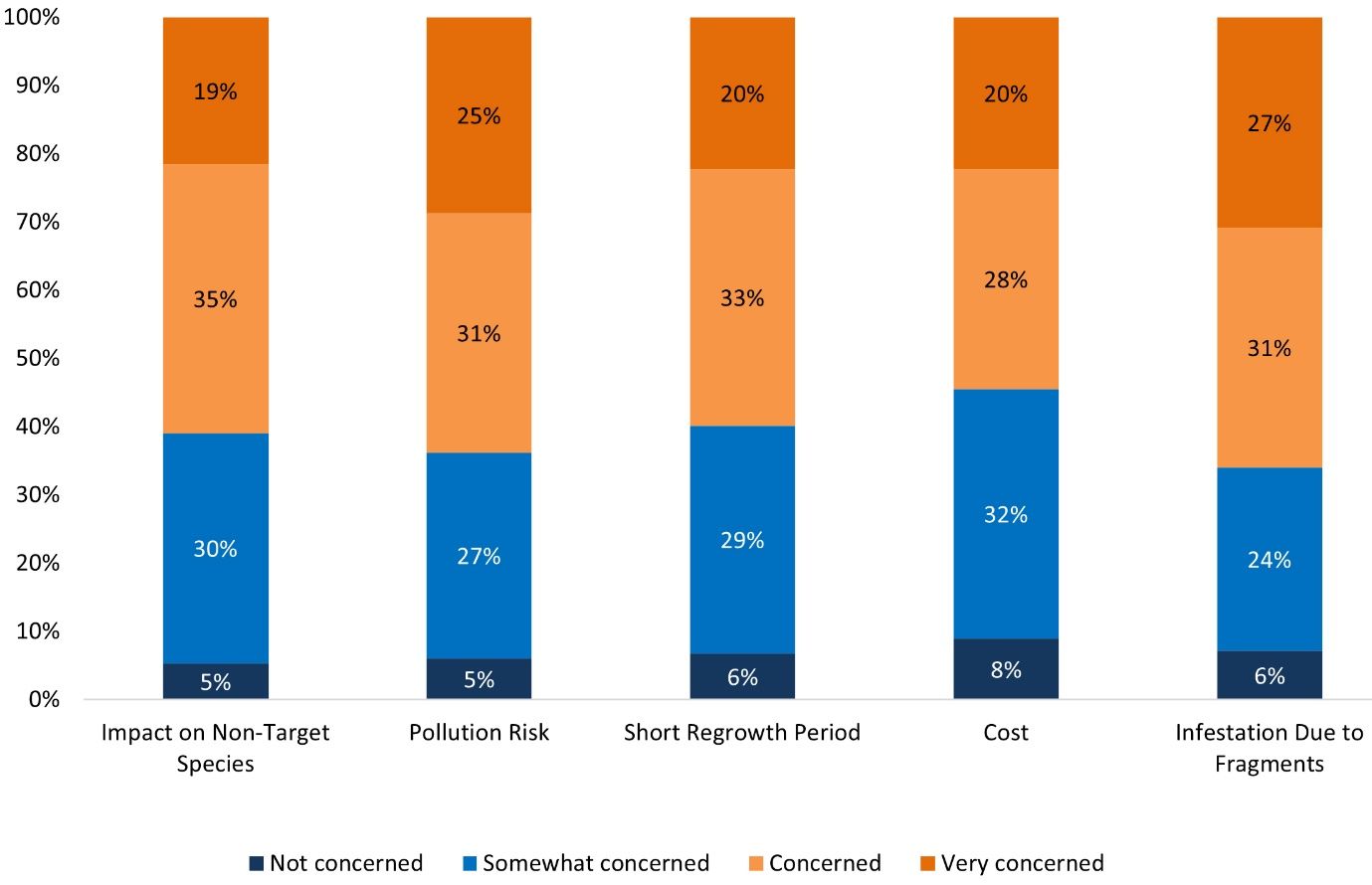

We also asked respondents to tell us whether they were concerned about any specific impacts that mechanical harvesting could potentially have. Concerns about the potential negative impacts on non-target species and the risk of pollution were among the factors that respondents found at least somewhat concerning. However, the levels of concern, as indicated by respondents who stated they were concerned or very concerned, were highest regarding the risk of hydrilla spreading to other lakes and water bodies if hydrilla plant fragments are not properly collected and disposed of. This was followed by worries over potential pollution from leaking gasoline or diesel fuel in lake water and the impacts of mechanical harvesting on non-target aquatic plants and animals.

Credit:

We also asked survey participants about their preferences for the hydrilla management approach. More than half of our respondents (52%) were in favor of using a combination of aquatic herbicides and mechanical harvesting.

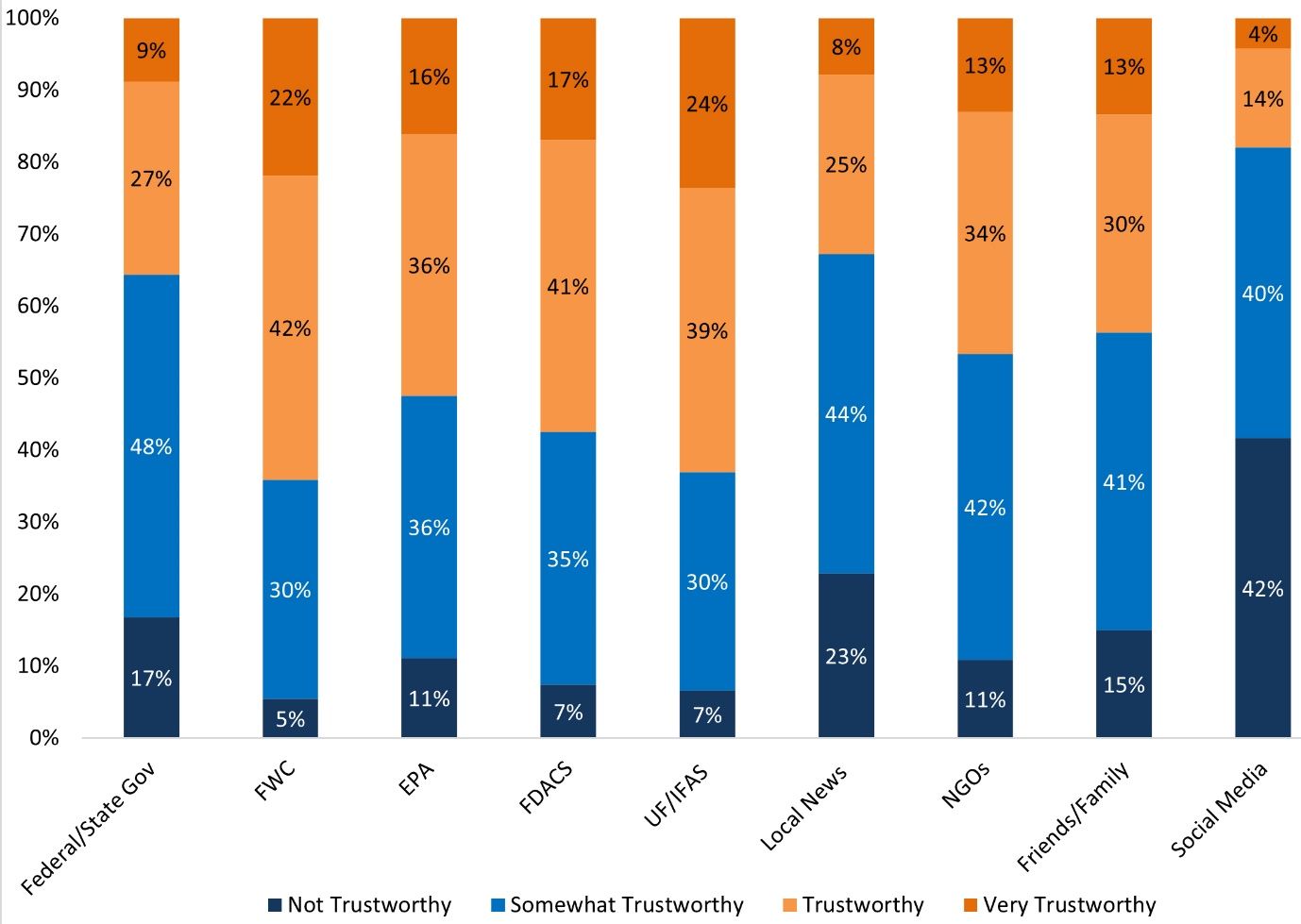

Finally, we inquired about the sources of information respondents most trusted regarding invasive species, as illustrated in Figure 10. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, closely followed by UF/IFAS and FDACS, stood out as the most trusted sources, according to the percentage of respondents who rated these agencies as very trustworthy, trustworthy, or somewhat trustworthy. However, both UF/IFAS and FWC received the highest percentages of very trustworthy ratings, at 24% and 22%, respectively. It is also worth noting that UF/IFAS leads in the combined percentage of responses in the trustworthy and very trustworthy categories. In contrast, respondents were overwhelmingly distrustful of social media content as their source of information (note, the social media accounts of other information sources, such as UF/IFAS, are not included in this option). Additionally, factors such as higher levels of income and education, more frequent visits to lakes, and access to information about management options were positively correlated with the perceived trustworthiness of these agencies.

Credit:

Conclusion

The management of hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) in Florida's public freshwater systems poses a complex challenge that is underscored by the diverse concerns of various stakeholder groups regarding the methods used to control this invasive aquatic plant. This publication presents the results of the largest state-wide survey of Florida residents aimed at identifying stakeholder perceptions around hydrilla and hydrilla management practices, as well as which sources of information on invasive species are trustworthy.

Our analysis reveals several key insights important for policymaking. We find that Florida residents are concerned about both hydrilla-management practices in use in the state—aquatic herbicide use and mechanical harvesting—but they express higher levels of concern about the use of aquatic herbicides to control hydrilla. Familiarity with hydrilla and its management practices is linked to reduced levels of concern over control measures. Interestingly, all stakeholder groups surveyed largely prefer a combination of methods for managing hydrilla, with 52% favoring the use of both aquatic herbicides and mechanical harvesting.

Public trust in information sources about invasive species is critical for public support of management strategies. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the University of Florida's Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences are considered the most trustworthy sources of information about invasive species management according to the survey results. This trust is important, because managing hydrilla effectively requires not only technical solutions but also public buy-in and informed engagement. By providing transparent, science-based information about the management of invasive species, these institutions can help mitigate concerns and foster supportive public attitudes.

These findings offer valuable information for policymakers, underlining the importance of understanding and addressing public perceptions before implementing control measures. Constituents who are satisfied that hydrilla management practices are safe and effective are essential to the development of and adherence to an effective management policy. As a national leader in invasive species management, Florida can act as a model for understanding constituents’ perceptions and effectively balancing technical solutions with public engagement for effective hydrilla management policy.

References

Enloe, S. F., L. A. Gettys, J. Leary, and K. A. Langeland. 2019. “Hydrilla Management in Florida Lakes: SS-AGR-361/AG370, Rev. 11/2019.” EDIS 2019 (November). Gainesville, FL:7. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ag370-2019

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2022. Hydrilla. My FWC. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/habitat/invasive-plants/weed-alerts/hydrilla/#:~:text=Hydrilla%20canopies%20produce%20ideal%20breeding,as%20boating%2C%20swimming%20and%20fishing.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2022. (rep.). Annual Report of Activities Conducted under the Cooperative Aquatic Plant Control Program in Florida Public Waters for Fiscal Year 2020–2021. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://myfwc.com/media/28949/annualreport20-21.pdf.

Gettys, L. A., and S. F. Enloe. 2019. “Hydrilla: Florida’s Worst Submersed Weed: SS-AGR-400/AG404, 2/2016.” EDIS 2016 (3). Gainesville, FL:7. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ag404-2016.

Hiatt, D., K. Serbesoff‐King, D. Lieurance, D. R. Gordon, and S. L. Flory. 2019. “Allocation of invasive plant management expenditures for conservation: Lessons from Florida, USA.” Conservation Science and Practice 1(7). https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.51

Hoyer, M. V., W. T. Haller, J. Ferrell, and D. Jones. 2022. “Legacy Herbicides in Lake Sediment.” Research Guide. https://plants.usda.gov/home/noxiousInvasiveSearch

Leary, J. 2020. “Working Harder to Make Hydrilla Harvesting Work.” Blog. UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. http://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/caip/2020/04/26/working-harder-to-make-hydrilla-harvesting-work/ (accessed 4.27.22).

Weber, M., L. Wainger, N. Harms, and G. Nesslage. 2021. The Economic Value of Research in Managing Invasive Hydrilla in Florida Public Lakes.” Lake and Reservoir Management 37 (1): 63–76 https://doi.org/10.1080/10402381.2020.1824047

USDA NRCS. 2015. Introduced, invasive, and noxious plants: Federal Noxious Weeds. United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service. Accessed December 7th, 2022, from https://plants.usda.gov/home/noxiousInvasiveSearch

Cite This Publication

Heinzmann, A., O. M. Savchenko, C. Prince, and J. Leary. 2024. “Navigating Public Perceptions: Exploring the Complex Social Dynamics of Invasive Species Management in Public Waters. FE1159.” EDIS 2024. Gainesville, Florida. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-FE1159-2024