Introduction

This publication provides information on the ecological benefits of some common plant species that occur in lawns of north central Florida, typically referred to as “weeds.” In this publication, we define the functions of lawns and their “weeds” both from cultural and ecological perspectives. We also discuss the benefits of allowing some non-turf species to persist in your lawn and provide the biological and ecological traits for a handful of common self-recruiting plants that may already be present in your lawn and that may be perceived as weeds. Additional resources are listed at the end of this publication to help identify the variety of plants that can occur in our lawns and to show readers how they can reduce dependence on water and chemical inputs, like fertilizers and pesticides, for lawn maintenance. The target audience of this publication is homeowners, green industry professionals, Extension agents, and anyone interested in urban ecology or urban plant diversity.

This publication serves as a resource for a growing international movement of people who want to reimagine lawns and enhance the environmental services that their yards can provide to urban and residential landscapes. The following are successful examples of programs aimed at achieving these goals:

- Bee Lawns, University of Minnesota (https://beelab.umn.edu/bee-lawn)

- Pollinators Lawns, Michigan State University (click here for article or here to watch video)

- New Neighbors of Montreal, Canada (https://nouveauxvoisins.org/)

What are lawns?

Culturally defined, lawns are areas dominated by grasses that are mowed, or maintained, at a short height. Highly managed lawns are typically valued for aesthetic quality, as recreational spaces, and as social gathering areas. Ecologically defined, properly managed lawns provide functions such as soil stabilization, nutrient uptake, and water filtration. Lawns may also provide essential food and shelter for a variety of living things through increased lawn plant diversity and structure. From an urban land-use perspective, lawns are a low-cost way to cover, and stabilize, bare soil in new developments. They also provide cooling effects and noise reduction.

Lawns make up at least 2% of land cover in the United States, more than any other conventional irrigated crop (Milesi and others 2005). Monoculture, or single species, lawns decrease biodiversity because the lawn is intentionally maintained to have a single dominant grass species. Additionally, there are few turfgrass species commercially available, historically six species in Florida (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/entity/topic/lawn_grasses). Improper turfgrass species selection and lawn management practices can lead to direct and indirect environmental impacts to nearby ecosystems that stem from overuse of water, chemicals, and other resources. Remember the Florida-Friendly LandscapingTM (FFL) principle of “right plant, right place” when selecting the proper turfgrass species and variety. Improper species selection may also impact your ability to follow other FFL principles of “water efficiently,” “fertilize appropriately,” and “manage pests responsibly.” Maintaining turfgrass monocultures, especially for improperly selected species, can be resource intensive, requiring significant water and chemical inputs to maintain healthy grass and prime aesthetic appeal. If fertilizer and/or pesticides are necessary, remember to always follow the label instructions when applying them to your lawn.

Weeds (defined below) are a part of lawns, and their presence plays an important role in how people choose to manage these landscapes. Nevertheless, the presence of what some may call a “weed” may not impact the aesthetic quality of lawns (Figure 1).

Credit: (A–B) by Olesya Malakhova, (C–D) by Basil Iannone

What are “weeds"?

Culturally defined, weeds are undesirable plants that grow where they are not wanted. An entire plant species cannot be classified as a “weed.” Context is needed. For instance, a native plant growing in the woods has ecological benefits to that ecosystem. But individuals of that same plant species could be classified as a “weed” if you do not wish them to grow in your flowerbed. Therefore, it is best to state that the species is a weed in my flowerbed, rather than just saying it is a weed. Ecologically defined, “weeds” are just naturally dispersed plants that grow where their needs are met; they are self-recruiting species. For instance, perhaps you have already noticed different types of plants growing in various areas of your lawn with different degrees of moisture and/or sunlight. These plant species grow in different locations because each can grow under the soil moisture and light conditions at those locations.

Removing these self-recruiting species requires time and money and may not be necessary to maintain the primary functions of lawns, e.g., soil stabilization. In addition, their presence, particularly the natives, increases the biodiversity in lawns, which is a key contributor to urban wildlife habitat, providing food resources, shelter, and space for reproduction (Hostetler et al. 2003). For example, lawns with more plant diversity can provide more types of food resources for herbivorous invertebrates (including pollinators), arthropods, and, consequently, wildlife higher up in the food chain (e.g., birds). Famed conservation biologist E. O. Wilson raised awareness of humanity’s need to conserve arthropods, referring to them as the “little things that run the world” (Wilson 1987). Lawns managed for a dominant turfgrass species are less likely to sustain as many types of these essential “little things” and consequently are less likely to provide the same amount of these benefits.

Despite the ecological importance of self-recruiting lawn plant species, most of the current information and marketing of turf focuses on killing them and preventing their further establishment. We would like to supplement commonly available information on weed control by presenting the ecological benefits of some common self-recruiting lawn species of north central Florida, enabling the reader to consider whether these species (and others) truly need to be controlled. Allowing for the presence of beneficial plant species that do not detract from the function of a lawn can help mitigate environmental impacts by reducingthe need for pesticides, fertilizer, and irrigation. Certainly there are some plant species that establish in lawns that will still require control; three such species are discussed below.

Identification of Plant Traits

The following section provides information on traits common to a handful of native self-recruiting lawn plant species that are usually considered “weeds.” These species are presented in order of growth height, from the lowest-growing groundcovers to wildflower species that mature at taller heights. We chose these species because they

- can tolerate mowing and will still flower when mowed, depending on mowing frequency,

- can add attractive color to a lawn via flowers, which also support pollinators, and

- are commonly found throughout north central Florida.

We provide information on traits that can assist readers, bothin identifying thesespeciesand in understanding theirhabitat needs, their growth characteristics, and their various ecological benefits. The traits provided are listed and described in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of each trait provided for common native lawn plant species.

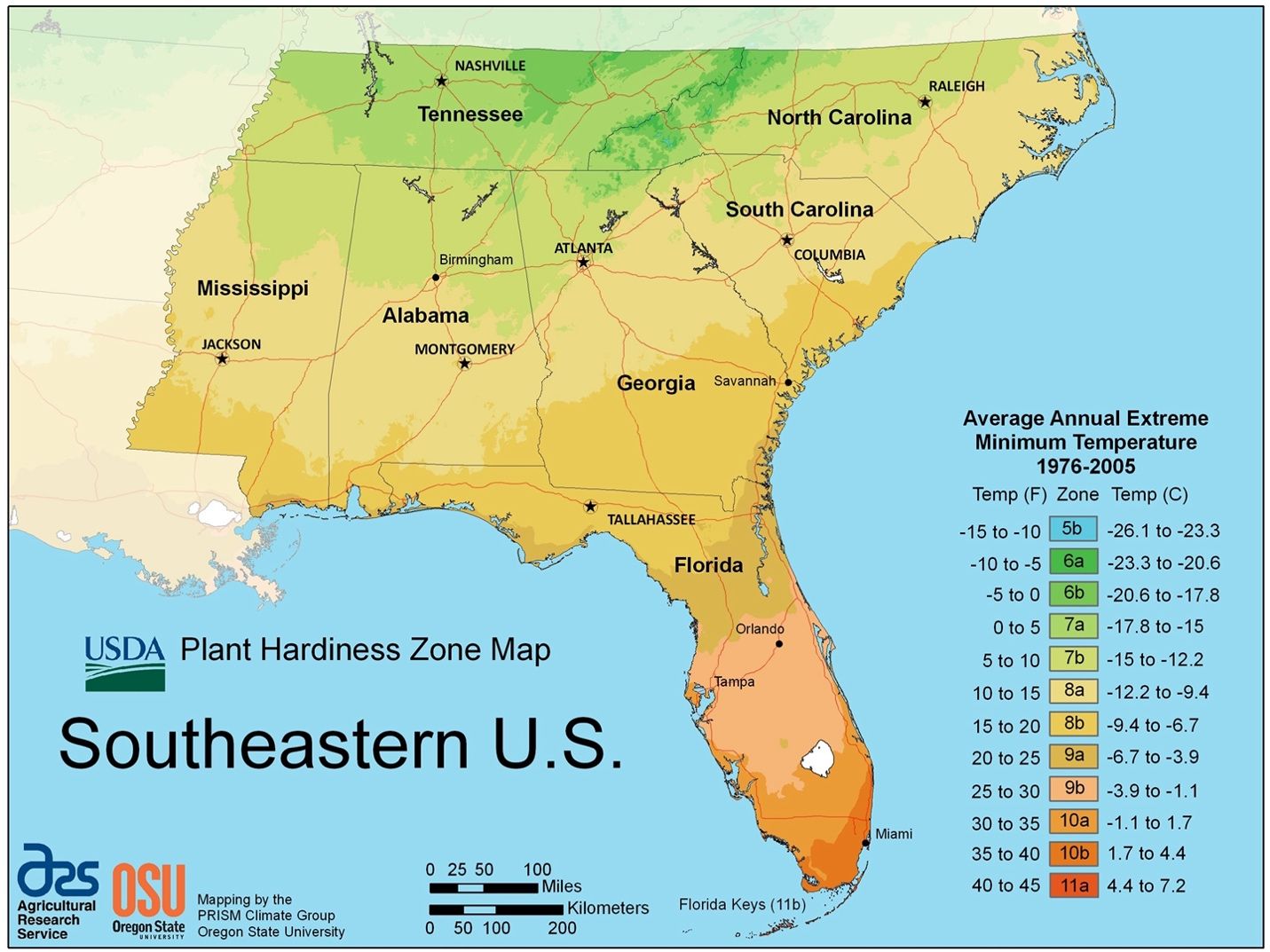

Credit: USDA

Common Native Beneficial Species

Partridgeberry, Twinberry (Figure 3)

Mitchella repens

Habit: Herbaceous low-growing plant. Older stems may become woody.Short-lived perennial with creeping habit. Grows up to 2 inches (5 cm) tall. Spreads vegetatively and by seed.

Flower: Two tubular white to purple flowers; blooms late spring to fall.

Hardiness Zone: 4A–9B

Soil: Sandy, loam, pH acidic to neutral

Light Requirement: Partial to full shade

Moisture Requirement: Somewhat moist to not extremely dry, shaded conditions. Not flood tolerant.

Propagation: Softwood divisions of rooted stems, seed

Dormancy: None

Availability: Native nurseries, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards)

Wildlife use: Birds and small animals eat the berries; attracts pollinators.

Host Plant: None found

Disease: None found

Other: Tolerates but does not require mowing due to its low growth habit. Naturally grows in woodland understories.

Credit: Doug McGrady, CC BY 2.0, via Flicker

Carolina Pony’s Foot (Figure 4)

Dichondra carolinensis

Habit: Perennial with spreading habit. Grows up to 2 inches (5 cm) tall. Spreads vegetatively and by seed.

Flower: White/green inconspicuous flower; blooms late winter through summer.

Hardiness Zone: 7A–11

Soil: Sandy; adaptable to varying pH (~6.1–7.8 pH)

Light Requirement: Full sun to partial shade

Moisture Requirement: Wet to moist soil conditions

Propagation: Transplant divisions 6–9 inches (15–22 cm) apart (i.e., dig up the plant and separate some rooted stems), seeds

Dormancy: None

Availability: Local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Source of nectar and pollen

Host Plant: Eaten by pink-spotted hawkmoth larva (Agrius cingulata)

Disease: Dichondra fungal rust (Puccinia dichondra)

Other: Tolerates but does not require mowing. Tolerates temporary flooding.

Credit: T. J. Butler, CC0 1.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sunshine Mimosa, Powderpuff, Sensitive Plant (Figure 5)

Mimosa strigillosa

Habit: Herbaceous legume, long-lived perennial with spreading habit. Grows up to 3 inches (7 cm) foliage and up to 6 inches (15 cm) flower. Spreads mainly vegetatively.

Flower: Pink flower; blooms spring to summer.

Hardiness Zone: 8A–11

Soil: Sandy, loam; around neutral (~6.5–7.5 pH)

Light Requirement: Full sun to partial shade

Moisture Requirement: Moist to very dry once established

Propagation: Transplant divisions 2–3 feet (0.6–1 m) apart, seed

Dormancy: Sometimes in the winter

Availability: Native nurseries (see FANN for availability), Florida Native Plant Society (FNPS) sales, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards)

Wildlife use: Source of nectar and pollen; white-tailed deer may graze the leaves; can be used by both game and non-game birds.

Host Plant: Larval host of little sulfur (Eeurema lisa) butterfly

Disease: None found

Other: Tolerates infrequent mowing, but you will lose flowers. Does not tolerate heavy foot traffic. Can spread aggressively into adjoining yards and plant beds without barriers.

Credit: Mary Keim, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr

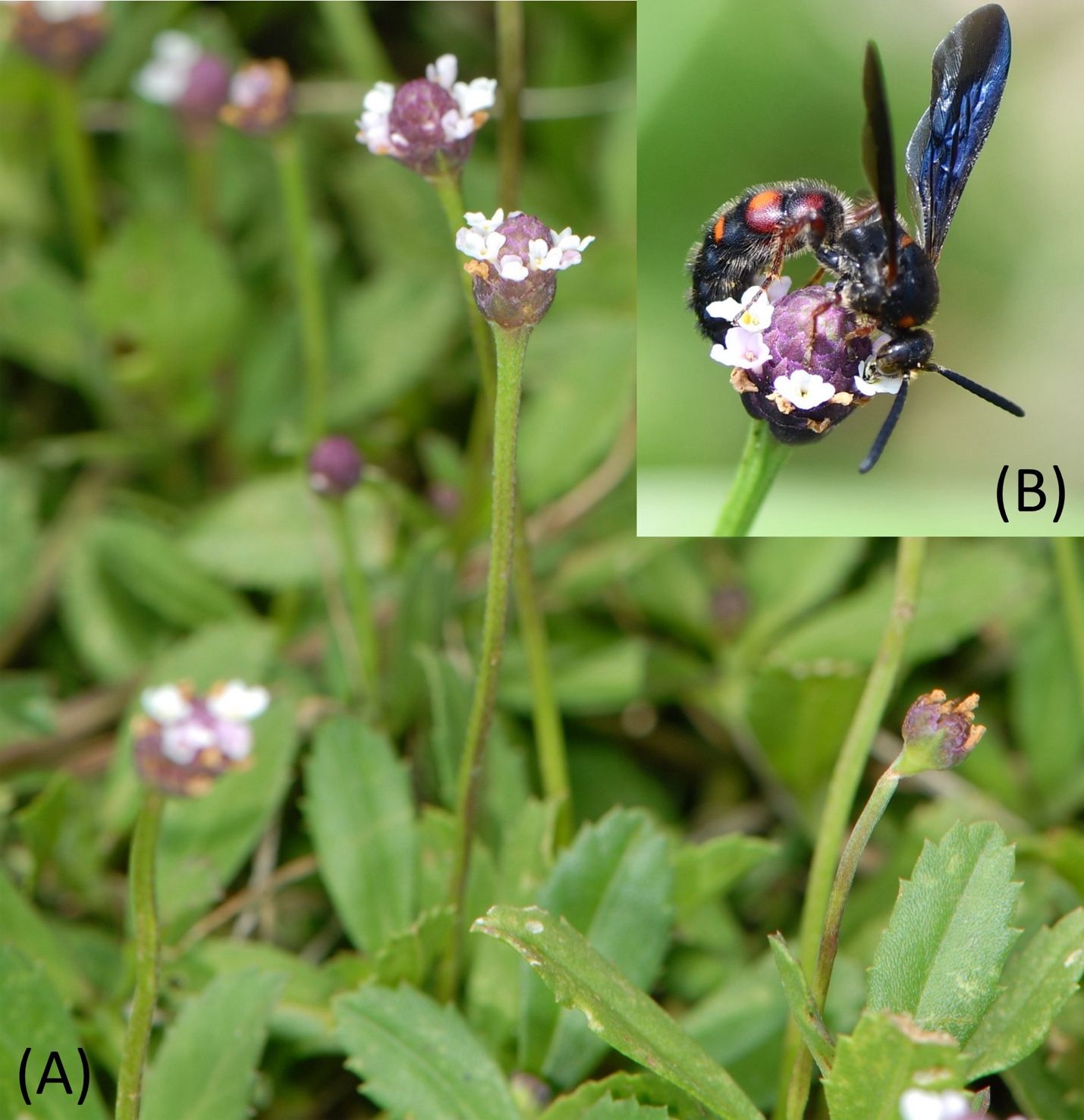

Frog fruit, Turkey tangle (Figure 6)

Phyla nodiflora

Habit: Herbaceous, long-lived perennial with spreading habit. Grows up to 3 inches (7 cm) foliage and up to 6 inches (15 cm) flower. Spreads mostly vegetatively.

Flower: White and purple; can bloom year round.

Hardiness Zone: 8A–11

Soil: Sandy, loam, clay; adaptable pH

Light Requirement: Full sun to partial shade

Moisture Requirement: Moist to not extremely dry. Drought tolerant once established.

Propagation: Transplant divisions 12 inches (30 cm) apart

Dormancy: Variable, i.e., some plants go dormant; others do not

Availability: Native nurseries, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards)

Wildlife use: Source of nectar and pollen for many species

Host Plant: Larval host for phaon crescent (Phycoides phaon), white peacock (Anartia jatrophae), hairstreaks (Theclinae), and common buckeye (Junonia coenia) butterflies.

Disease: Minor host to southern root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) and Pierce’s disease of grapevines (Xylella fastidiosa). Susceptible to fungal diseases, like southern blight, when overirrigated.

Other: Can tolerate temporary moderate flooding and foot traffic.

Credit: (A) by Sam Fraser-Smith, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr; (B) by Sandra B. Wilson, UF/IFAS

Creeping Wood Sorrel (Figure 7)

Oxalis corniculata

Habit: Short-lived perennial with spreading habit, clumping at nodes. Grows up to 4 inches (10 cm) tall and in groups up to 2 feet (60 cm) wide. Green to reddish foliage depending on sun exposure. Reseeds readily.

Flower: Yellow flower; blooms early spring through fall or year-round where conditions are favorable.

Hardiness Zone: 4A–10A

Soil: Sandy, loam; slightly acidic to alkaline (~6–7.8)

Light Requirement: Full sun to partial shade

Moisture Requirement: Somewhat moist to not extremely dry

Propagation: Transplant divisions 12 inches (30 cm) apart, seed

Dormancy: Sometimes in winter

Availability: Local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Source of nectar and pollen

Host Plant: Root-knot nematodes

Disease: Whitefly and mites

Other: Small fruit capsule explosively launches seeds when ripe and/or disturbed.

Credit: koobonsil, via Pixabay

Bristle Basketgrass (Figure 8)

Oplismenus setarius

Habit: Grass, short-lived perennial with spreading habit, rooting at nodes. Grows up to 4 inches (10 cm) tall. Spreads vegetatively and by seeds

Flower: Inconspicuous red floral parts growing in a spike; blooms summer to fall.

Hardiness Zone: 7B–10B

Soil: Sandy, loam, pH acidic to neutral

Light Requirement: Partial to full shade

Moisture Requirement: Somewhat moist to dry conditions

Propagation: Transplant divisions 9–12 inches (22–30 cm) apart, seed

Dormancy: Winter

Availability: Local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Seeds as food resource for many species, including the painted bunting.

Host Plant: Larval host for Carolina satyr.

Disease: None found

Other: May be confused with other species like non-native Oplismenus burmanii because of visual similarity and hybridization.

Credit: Olesya Malakhova, UF/IFAS

Lyre-leaf Sage (Figure 9)

Salvia lyrata

Habit: Perennial. Grows in a rosette. Foliage grows up to 6 inches (15 cm) and flowers upto 2 feet (60 cm) tall. Reseeds readily.

Flower: Blue/lavender tubular flowers in a spike emerging from the rosette. Blooms late winter to spring; rarely blooms in the summer.

Hardiness Zone: 5B–10B

Soil: Sandy, loam, clay; adaptable, around neutral (~6.8–7.2 pH)

Light Requirement: Full sun to full shade

Moisture Requirement: Highly adaptable and tolerant of varying moisture conditions

Propagation: Transplant summer divisions 12 inches (30 cm) apart; seed (seeds require cold stratification).

Dormancy: Winter

Availability: Native nurseries, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Source of nectar for hummingbirds, butterflies, and bees

Host Plant: Aphids (a food source for ladybug larvae)

Disease: None found

Other: Tolerates infrequent mowing. Not tolerant of foot traffic.

Credit: Olesya Malakhova, UF/IFAS

Common Purslane (Figure 10)

Portulaca oleracea

Habit: Annual with sprawling habit that can tolerate nutrient-poor dry soils. Grows up to 9 inches (22 cm) tall. Reseeds readily.

Flower: Yellow to red solitary flower; blooms early summer till frost.

Hardiness Zone: 2A–11B

Soil: Sandy, loam, pH acidic to neutral

Light Requirement: Full sun

Moisture Requirement: Prefers dry, well-drained soils. Drought tolerant.

Propagation: Transplant 9–12 inches (22–30 cm) apart, seed

Dormancy: Winter

Availability: Big box stores (cultivars), local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Seeds and foliage are edible to birds and deer. Flowers attract sweat flies.

Host Plant: Larva of the purslane sawfly (Schizocerella pilicornis) and the portulaca leaf mining weevil (Hypurus bertrandi)

Disease: Various fungal diseases when conditions too moist

Other: Portulaca pilosa is another similar species (with more slender/linear leaves and purple flowers) that can also be used in mixed grass landscapes.

Credit: Ethel Aardvark, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Dollarweed, Pennywort (Figure 11)

Hydrocotyle umbellata

Habit: Perennial with spreading habit due to underground stems. Grows up to 10 inches (25 cm) tall. Spreads mainly vegetatively.

Flower: Small white flowers in cluster; blooms sporadically year round.

Hardiness Zone: 4A–10A

Soil: Sandy, loam, clay, pH acidic to neutral

Light Requirement: Full sun to full shade

Moisture Requirement: Areas that stay wet to areas with moist soils

Propagation: Transplant divisions 6 feet (2 m) apart, seed

Dormancy: None

Availability: Native nurseries, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Plants in aquatic areas provide habitat for invertebrates; seeds are eaten by waterfowl. Attracts insects including these families: sweat bees (Halictidae), spider wasps (Pompilidae), thread-waisted wasps (Sphecidae), hornets (Vespidae).

Host Plant: Leaf miners (larva of many species of insects)

Disease: None found

Other: Spreads quickly in favorable conditions. Absorbs (bioaccumulates) toxic pesticides and pollutants. Presence in lawns suggest wet soils or excessive irrigation.

Credit: Scott Zona, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr

Cutleaf Evening Primrose (Figure 12)

Oenothera laciniata

Habit: Biennial to perennial. Grows up to 4–18 inches (10–45 cm) tall. Spreads by seed.

Flower: Yellow to pinkish flowers; blooms early spring to fall.

Hardiness Zone: 8A–11

Soil: Sandy, lime rock; pH tolerance is acidic to calcareous.

Light Requirement: Full sun to part shade

Moisture Requirement: Moderate to extremely dry. Tolerant of very long dry periods.

Propagation: Transplant divisions 9–12 inches (22–30 cm) apart, seed

Dormancy: Winter

Availability: Native nurseries, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Recognized by pollination ecologists as attracting large numbers of native bees. Also attracts moths and butterflies. Deer may feed on leaves. Birds like the bobwhite (Colinus virginianus), mourning dove (Zenaida macroura), and gold finch (Spinus tristis) eat the seeds.

Host Plant: Insects in these families: wasps (Vespidae), aphids (Aphididae), ladybugs (Coccinelidae), plant bugs (Miridae) (the tarnished plant bug is a pest in cotton production)

Disease: Leaf spot and root rot possible when moisture is high.

Other: Tolerates infrequent mowing. Flowers open from dusk to dawn.

Credit: Sandra B. Wilson, UF/IFAS

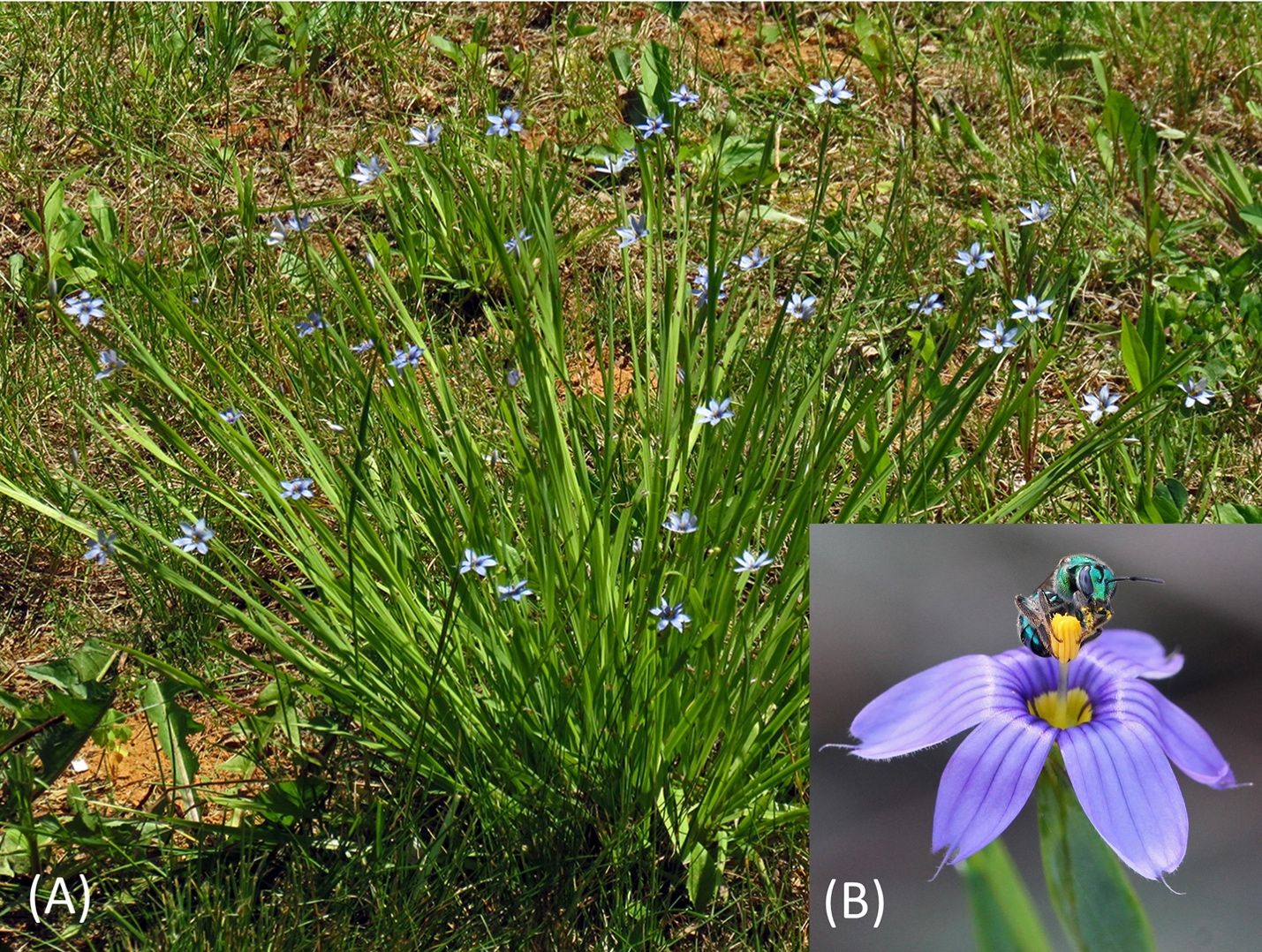

Blue-eyed Grass (Figure 13)

Sisyrinchium angustifolium

Habit: Herbaceous with grass-like foliage. Short-lived perennial with clumping habit. Grows up to 1 foot (30 cm) tall and 1 foot (30 cm) wide. Reseeds readily.

Flower: Blue/violet flower with yellow center; blooms early spring to summer.

Hardiness Zone: 4A–11

Soil: Sandy, loam, slightly acidic to neutral (~6.0–7.0 pH)

Light Requirement: Full sun to partial shade

Moisture Requirement: Occasionally saturated areas to non-wet, moderately droughty

Propagation: Transplant divisions 9–12 inches (22–30 cm) apart, seed

Dormancy: Winter

Availability: Native nurseries, FNPS sales, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Good source of nectar and pollen for sweat bees, bumble bees, bee flies, and hover flies; seeds provide food to wildlife such as birds.

Host Plant: None found

Disease: None found

Other: Tolerates infrequent mowing. Has grass-like leaves but is actually in the iris family.

Credit: (A) by BlueRidgeKitties, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr; (B) by Mary Keim, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr

Carolina Wild Petunia (Figure 14)

Ruellia caroliniensis

Habit: Short-lived perennial with spreading habit. Grows as short lawn plant up to 4 inches (10 cm) tall or as herbaceous shrub up to 2 feet (60 cm) tall and 2 feet (60 cm) wide when left unmowed. Reseeds readily.

Flower: Blue/lavender flower in clusters (1–4) at leaf node; blooms early spring to late summer.

Hardiness Zone: 6A–11

Soil: Sandy; alkaline (~7.9–8.5 pH)

Light Requirement: Full sun to full shade

Moisture Requirement: Moist to areas that experience somewhat long dry periods

Dormancy: Winter

Availability: Native nurseries, FNPS sales, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Propagation: Transplant summer divisions 6–9 inches (15–22 cm) apart, seed (seeds require cold stratification).

Wildlife use: Source of nectar and pollen

Host Plant: Larval host for common buckeye (Junonia coenia) and white peacock (Anartia jatrophae) butterflies

Disease: White “fuzzy” patches that look like fungus but are colonies of gall mites (Acalitus ruelliae)

Other: Mow after plants go to seed (about two months after flower withers).

Credit: Mary Keim, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr

Spiderwort (Figure 15)

Tradescantia ohiensis

Habit: Herbaceous long-lived perennial. Grows up to 1 foot (30 cm) tall foliage and up to 3 feet (1 m) tall flower, 2.5 feet (75 cm) wide. Reseeds readily

Flower: Blue/lavender flower cluster on stalk. Blooms in early mornings from late winter to fall.

Hardiness Zone: 4A–9A

Soil: Sandy, loam, lime rock; adaptable pH

Light Requirement: Full sun to partial shade

Moisture Requirement: Moist areas, occasionally saturated to very dry conditions

Propagation: Transplant divisions 9–12 inches (22–30 cm) apart, seed

Dormancy: Only during cold winters

Availability: Native nurseries, FNPS sales, local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Source of nectar and pollen. Foliage may be eaten by deer and rabbits.

Host Plant: Larval host to owlet moth (Mouralia tinctoides)

Disease: None found

Other: Tolerates infrequent mowing. Spreads quickly in favorable conditions. Mow after blooming before seeds mature (to reduce spread), or mow after seeds mature (to encourage reseeding). Aggressive in recently disturbed or cultivated soils.

Credit: Mary Keim, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr

Florida Betony, Rattlesnake Weed (Figure 16)

Stachys floridana

Habit: Perennial with spreading habit due to underground stems and tubers. Grows up to 2 feet (60 cm) tall. Spreads mainly vegetatively.

Flower: White to lavender flower in spike, blooms early spring to early fall

Hardiness Zone: 7A–11

Soil: Sandy, loam, pH adaptable

Light Requirement: Full sun to full shade

Moisture Requirement: Areas that are usually moist to areas that are not wet or are moderately dry

Propagation: Tubers, transplant summer divisions 9–24 inches (22–60 cm) apart, seed (low germination rate unless cold stratified)

Dormancy: Winter

Availability: Local resources (i.e., friends’ yards), seed

Wildlife use: Source of nectar and pollen

Host Plant: None found

Disease: None found

Other: Tolerates frequent mowing. Spreads quickly in favorable conditions and difficult to remove once established due to tubers, which are edible and taste like a mild radish.

Credit: Olesya Malakhova, UF/IFAS

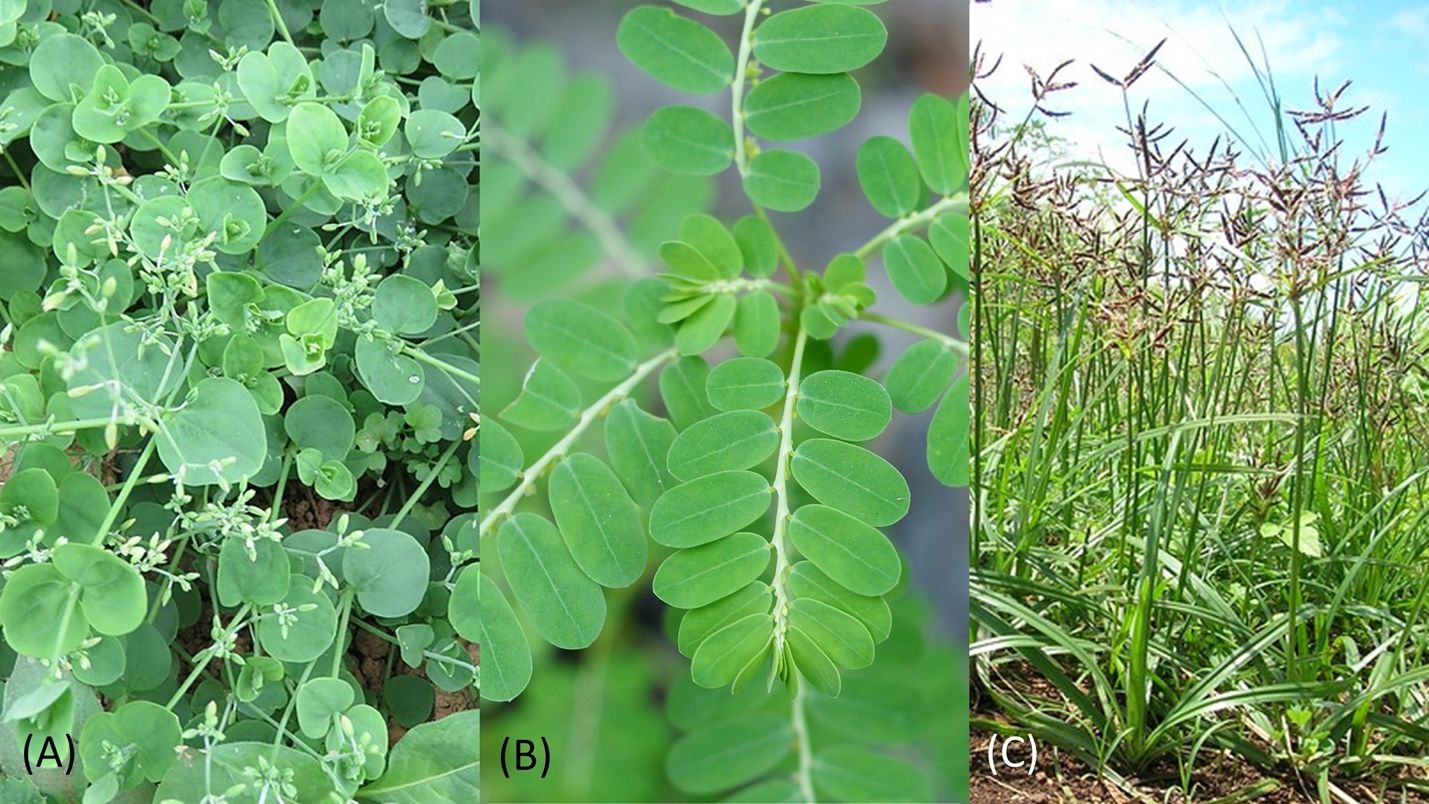

Common Species That Require Control

Not all plants found in lawns should be considered beneficial, and some may require control; see examples in Figure 17. Some lawn plants spread aggressively, detract from the function of lawns, and are categorized as “invasive,” i.e., nonnative plants that cause environmental and/or economic harm (Iannone and others 2021). The Florida Plant Atlas, Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI) Invasive Species Compendium, and IFAS Assessment, all discussed below, are resources that can be used to determine a species’ invasiveness to Florida.

Resources for Plant Identification and Alternative Lawn Recommendations

There are many resources for readers to learn about the diversity of plant species growing in our lawns and how to manage these landscapes for improved ecological benefit. Here, we list a few of these resources and their utility:

- Florida Association of Native Nurseries (FANN): Information on purchasing, growing, and promoting Florida native plant landscaping. Visit https://www.fann.org/

- Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ (FFL): Recommendations and examples of landscaping, other than turfgrass, that incorporate different textures, colors, and structures. Additionally, nine landscaping principles for conserving resources and protecting the environment are outlined. Visit https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/. Download their app (click here)

- Florida Native Plant Society (FNPS): Has information on Florida native flora and some of the plants’ growth requirements. Visit https://www.fnps.org/

- Florida Plant Atlas: Has information on the native status of a species relative to Florida. This resource usually does not contain information on cultivated species. Visit https://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/

- Florida Weeds Identification: Information on common Florida agricultural and landscape weeds. There are images and videos to describe the plants and some suggestions for management, if necessary. There are additional useful links throughout the site. Visit https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/care/weeds-and-invasive-plants/florida-weed-id/

- Identifying sedges: Brief article on identifying common sedges. Provides additional resources for management of sedges when needed. Visit UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions (click here)

- iNaturalist: Website and phone app using artificial intelligence technology and other members of the online community to help identify species of plants, animals, and other organisms. By uploading pictures and additional information, you are likely to find a species name for the plant in question. Visit https://www.inaturalist.org/

- UF/IFAS Assessment: Reports on the potential risk of planting certain non-native species. An informative tool for reducing plant invasions in Florida. Visit https://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu/

- Additional reading: Nature’s Best Hope by Douglas W. Tallamy and Planting in a Post-Wild World by Thomas Rainer and Claudia West.

For more information on alternative lawn substitutes, try the search terms “UF/IFAS alternative groundcovers.”

Credit: (A) by Vinayaraj, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons; (B) by Prenn, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons; (C) by Forest and Kim Starr, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr

Conclusion

This publication aims to help people become more observant, open-minded, and accepting of beneficial self-recruiting lawn plants. Our goal is to change people's perspective of native self-recruiting species by sharing insight on their ecological value and how they do not necessarily detract from the intended functions of lawns. As there are some non-native species with ecologically detrimental traits, and because some plants that can compromise key functions of lawns, some lawn plants may still require control. Therefore, you should carefully identify species before considering their management. Given that plants will naturally travel from lawn to lawn, you may wish to share this information about the benefits of many self-recruiting lawn species with your neighbors and the greater community. Increased awareness of native lawn plants can help residents to choose how they manage lawns to be more ecologically beneficial to urban landscapes. Allowing recruitment is a strategy that can decrease the resources needed to maintain a functioning lawn while contributing to the overall benefits that lawns provide.

References

Hostetler, M. E., G. Klowden, S. W. Miller, and K. N. Youngentob. 2003. “Landscaping Backyards for Wildlife: Top Ten Tips for Success” Circular 1429/UW175, 1/2003. EDIS 2003 (1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-uw175-2003

Iannone, B. V. III, E. C. Bell, S. Carnevale, J. E. Hill, J. McConnell, M. Main, S. F. Enloe, S. A. Johnson, J. P. Cuda, S. M. Baker, and M. Andreu. 2021. “Standardized Invasive Species Terminology for Effective Education of Floridians.” FOR730/FR439, 8/2021. EDIS 2021 (4): 8. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fr439-2021.

Milesi, C., S. W. Running, C. D. Elvidge, J. B. Dietz, B. T. Tuttle, and R. R. Nemani. 2005. “Mapping and Modeling the Biogeochemical Cycling of Turf Grasses in the United States.” Environmental Management 36:426–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0316-2

Wilson, E. O. 1987. “The Little Things That Run the World (the Importance and Conservation of Invertebrates).” Conservation Biology 1 (4): 344–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.1987.tb00055.x