Riparian zones link upland and aquatic habitats.

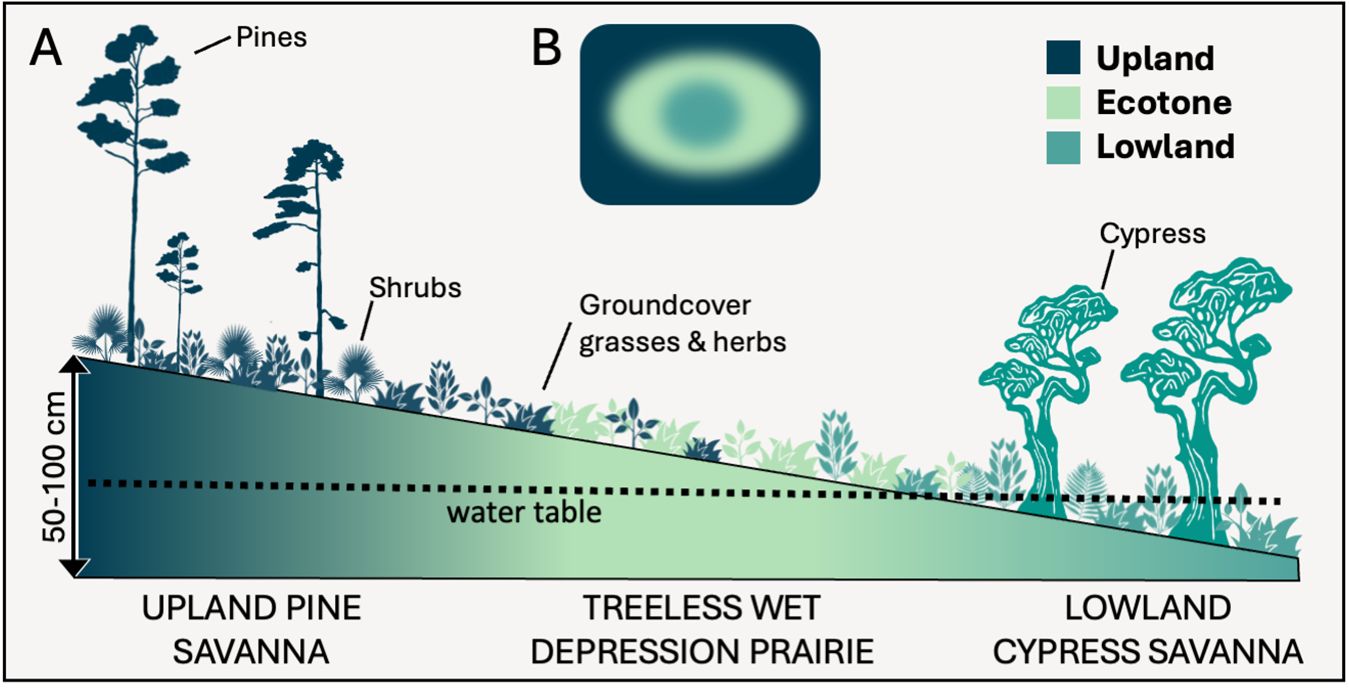

Riparian zones are ecotones, or transition areas, that occur between and connect a body of water and upland habitat (Svejcar 1997; Kirkman et al. 1998; Ilhardt, Verry, and Palik 2000; Figure 1). They include the plants, animals, and other organisms that live there, whether temporarily or permanently. Riparian zones link adjacent water and upland habitats by their shared materials, organisms, and energy (Baxter, Fausch, and Saunders 2005). These environments provide many ecosystem services (Box 1) or benefits to humans (Naiman and Décamps 1997; Ewel et al. 2001; Riis et al. 2020).

In the southeastern United States, freshwater habitats include springs, streams, rivers, lakes, ponds, and wetlands. These habitats all have riparian zones that differ based on the characteristics of the aquatic and upland habitats. Riparian zones may have unique species specifically adapted to the transition area in addition to a subset of species from both the aquatic and upland habitats (Naiman and Décamps 1997). Thus, management decisions should consider these characteristics and additional factors that can impact them, such as fire.

- Control flooding, erosion, and sediment deposition

- Improve water quality and recharge ground water

- Process and cycle nutrients

- Regulate local climate conditions (e.g., temperature, moisture)

- Mitigate the effects of fire

- Provide recreational opportunities

Fires are frequent in many southeastern US ecosystems, yet the impact of fires on riparian zones in this region is often comparatively smaller than the impact on the adjacent upland habitat. More information on fire management in North American riparian zones comes from the western United States. Therefore, this publication relates that research to riparian zones in the southeastern United States, and emphasizes impacts to riparian zones of Florida that experience frequent fire (Box 2; Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI) 2010; Brenner et al. 2014). This publication provides general prescribed fire management considerations for land managers and landowners and highlights three factors known to affect fire behavior in riparian zones: vegetation, topography, and weather. Fire behavior is highlighted because it is directly linked to fire intensity, fire spread, duff consumption, and dispersion of smoke (Johnson and Miyanishi 1995; Clark et al. 2020; Hiers et al. 2020). The use of riparian zones as firebreaks is also addressed. Finally, the effects of previous land management on fire behavior are also discussed. Bolded terms appear in the Glossary of Relevant Fire Terms following this section.

Credit: Raelene M. Crandall, UF/IFAS

Glossary of Relevant Fire Terms

- Atmospheric Dispersion Index is a scale that predicts the ability of smoke to rise and disperse and therefore not harm human health or reduce visibility on the ground. Values over 30 are strongly recommended to conduct prescribed burns.

- Buffering capacity refers to a habitat’s ability to resist burning.

- Duff is the layer of partially decomposed organic matter below freshly fallen litter (e.g., pine needles) and above the mineral soil.

- Fuel loading quantifies the amounts, distribution, and types of fuels (woody vs. herbaceous). These factors directly influence fire behavior and intensity. Fuel loads in riparian zones vary based on factors such as fire history, vegetation, elevation, and characteristics of the adjacent water body.

- Fuel moisture content refers to the amount of water in a fuel (e.g., plant matter). The moisture content of that fuel influences how it burns. Because of their proximity to water, plants that grow in the riparian zone typically have higher fuel moisture content and tend to burn less frequently or intensely than plants in drier habitats.

- Hydrarch (or hydrosere) succession is when the soil surface of a wetland slowly builds up from deposition of organic matter and sediment until it ultimately becomes level with the surrounding non-wetland landscape.

- Hydroperiod is the duration a water body remains flooded or inundated and the season(s) in which this occurs.

- Keetch-Byram Drought Index is a continuous reference scale for estimating the dryness of the soil and the duff layer.

- Peat is soil that has developed from accumulated vegetation biomass in wetlands.

Fire behavior in the riparian zone is influenced by vegetation.

Riparian zones can reduce fire intensity. Their vegetation (i.e., fuel) tends to have greater fuel moisture content, and the local relative humidity tends to be higher than in the surrounding uplands (Dwire and Kauffman 2003; Pettit and Naiman 2007). Where fire frequency is occasional to rare, the riparian zone typically includes more plant species sensitive or intolerant to fires (Pettit and Naiman 2007). In Florida riparian zones, fire-sensitive habitats typically include habitats dominated by hardwoods with a dense canopy or where there is woody encroachment, especially from shrubs (e.g., from titi) (Box 2; Florida Natural Areas Inventory [FNAI] 2010; Hess 2014). Thus, if riparian zones burn when water levels are elevated, fires are likely to be patchy, increasing the likelihood of these fire-sensitive plant species escaping the fire (Pettit and Naiman 2007; Crandall and Platt 2012). In addition, when water levels are elevated, riparian zones can be used as natural firebreaks (Pettit and Naiman 2007). When water levels are low, the fuel moisture content of plants will also be relatively low. This is when fires are more likely to spread from uplands into riparian zones, leading to more intense fires and greater mortality of fire-sensitive plants. Increasing fire frequency in riparian zones when water levels are low can lead to the replacement of fire-sensitive plant species with fire-resilient species (Naiman and Décamps 1997; Pettit and Naiman 2007), including more groundcover grasses and herbs in Florida (Huffman and Blanchard 1991; Kirkman et al. 1998). The latter plant species are likely to survive or recolonize after fires, resprouting from rhizomes, root crowns, or seed banks. Managers planning prescribed burns in a riparian zone should thus consider the overall fire frequency in the adjacent upland habitat, the water levels in the aquatic habitat, and whether fire-sensitive species, fire-resilient species, or a combination of both is desirable in the riparian zone.

Wetlands and their riparian zones deserve a closer look for prescribed fire management considerations. Pine savannas in Florida can often be dotted with wetlands that range from depression marshes to cypress dome swamps (Florida Natural Areas Inventory [FNAI] 2010). Historically, fires occurred in most of these habitats because charcoal layers have been found in soil cores taken from wetlands. However, fire frequency depends on wetland type, riparian vegetation, and the adjacent upland habitat (Box 2; Kuhry 1994). Without fires, organic plant material accumulates and decomposes slowly in wetlands due to low oxygen levels (Davis 1979; Watts et al. 2015). This buildup of organic material can eventually fill the wetland. With enough buildup, the wetland and vegetation can transition into a prairie or forest, with predictable consequences for biota and future fire behavior (Huffman and Blanchard 1991; Bishop and Haas 2005). This process is called hydrarch succession or hydrosere succession (Box 3; Kelley and Batson 1955; Kirkman 1995).

- Hardwood forested uplands (infrequent fire)

- Alluvial stream/river

- Blackwater, seepage, and spring-run streams

- Wetlands (infrequent burns* often lead to high plant mortality, though can be part of natural processes)

- Lakes

- Pine savannas, scrub, and dry prairies (occasional to frequent fire)

- Blackwater, seepage, and spring-run streams

- Wet prairies (often burn* unless encroachment by woody species)

- Marshes (often burn* during low hydroperiods)

- Bogs (can burn* every 10–20 years with extended drought)

- Swamps (low-intensity fires* often beneficial if peat does not burn)

- Lakes

Riparian zone fire frequencies are similar to fire frequencies in upland habitat, though variations occur and specialized management considerations are discussed throughout this publication.

*= aquatic habitat fire

As hydrarch succession transpires, the vegetation in a transitioning wetland also changes (Kimura and Tsuyuzaki 2011). Wetlands in fire-managed landscapes often support obligate wetland species, or plants that require constant water. These obligate wetland plants can survive by floating or have traits that allow them to survive being submerged. In habitat that is undergoing hydrarch succession and thus transitioning from open water to riparian zones, these water-dependent plants die and are replaced by plants that are less likely to survive partial or periodic submersion but that thrive in the riparian zone and are usually a mix of fire-sensitive and fire-resilient species (Huffman and Blanchard 1991; Kirkman 1995; Crandall and Platt 2012). As hydrarch succession continues, the riparian zone transitions to bottomland hardwood forest, open prairie, or savanna plant communities that only persist after minor and short-duration flooding. Simultaneously, the plant species transition to those that are adapted to survive in these upland habitats, and the obligate wetland species will disappear (Kimura and Tsuyuzaki 2011).

Fire can reverse hydrarch succession in wetlands (Davis 1979), though this is an uncommon management goal due to air quality concerns, as the accumulated duff can burn for extended periods (Watts et al. 2015). During droughts, fires often burn the previously submerged accumulated organic matter down to the underlying mineral soil. This can reverse the process of hydrarch succession; a different plant community will emerge; and different fauna will return (Bixby et al. 2015). Many species depend on wetlands for at least a part of their life cycle, and some rely on wetlands for their entire life. The dynamic nature of wetland riparian zones and vegetation succession is thus influenced by fire. While most managers will avoid burning wetlands with high levels of accumulated duff, understanding the riparian zone vegetation (in particular fuel moisture content and fire-sensitive and fire-resilient species) and how that will influence fire behavior is critical for burning in and around these systems. For wetlands with lower duff levels, relatively frequent, low- to moderate-intensity riparian zone and/or wetland burning can be beneficial, particularly to manage woody encroachment (Hess 2014).

Fire Impacts upon Wildlife

Riparian zones can provide temporary refuge for wildlife during burning (Pettit and Naiman 2007) or benefits following burning (Stratman 1998; Moseley, Castleberry, and Schweitzer 2003; Allen et al. 2006). Many animals instinctively move away from fire into riparian zones where fires are less likely. In contrast, when riparian zones cannot buffer the movement and intensity of fires, animals that live in the riparian zone, such as invertebrates (e.g., insects) or amphibians, may decrease in numbers because of the lack of adequate cover (Steel et al. 2019). Other species may rely on frequent fire for their habitat, where fire seasonality can be critical (Russell, Van Lear, and Guynn, Jr. 1999; Bishop and Haas 2005). After fires, aquatic communities can be temporarily harmed by increased sediment, reduced shading, and altered food resources (e.g., leaves vs. ash from the riparian zone). The severity of the fire and the riparian zone's post-fire recovery determines the magnitude and duration of the impact (Verkaik et al. 2013; Cooper et al. 2015). In addition, managers will often implement firebreaks around riparian zones when fire movement into the riparian zone or aquatic habitat is undesirable. However, firebreaks can have detrimental impacts on the habitat or organisms by altering the natural hydrology and vegetation (Ward et al. 2024). In Florida riparian zones, managers can focus on target organisms like flatwoods salamanders (Bishop and Haas 2005) or gopher frogs (Humphries and Sisson 2012) or general groups (e.g., wading birds and reptiles) that can benefit from fire in riparian zones and the aquatic habitat (Moseley, Castleberry, and Schweitzer 2003; Allen et al. 2006) to determine how fire can be appropriately leveraged as a management tool in these areas, including when firebreaks are appropriate.

Alternatively, some animals influence the buffering capacity of the riparian zone. Because areas near beaver dams are less likely to burn, fires in riparian zones where beavers are common will likely have heterogeneous (mixed) levels of burn severity compared to fires in similar habitat without beavers. Beaver activity in the riparian zone may also inhibit the spread of fire to the aquatic habitat. Beavers are known as ecosystem engineers because they change water flow with their dams, causing the water to extend laterally. The extension of this water buffers the vegetation against fire, increasing the riparian zone's fuel moisture content and width (Wheaton 2018; Fairfax and Whittle 2020; Figure 2). Fire-sensitive vs. fire-resilient plants, fuel loading, and fuel moisture content will also influence fire behavior. Land managers planning to implement prescribed burns near aquatic habitats should consider how wildlife in the area will affect the riparian vegetation and vice versa.

Credit: Joseph Wheaton (Utah State University) Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Fire behavior in the riparian zone is influenced by weather, particularly seasonality.

Another key concern for land managers is the seasonality of fires (e.g., growing-season fire vs. dormant-season fire; rainy-season fire vs. dry-season fire). Seasonality affects both fire behavior and vegetation recovery in riparian zones (Platt, Orzell, and Slocum 2015; Chiodi, Larkin, and Varner 2018; Vaughan et al. 2021). Even within the southeastern United States and Florida ecosystems, where the obvious temperature fluctuations that mark the seasons of the year in northern regions are less extreme, regional weather differences do still influence water levels seasonally, and managers must understand these seasonal changes to properly plan for prescribed burns. In particular, the buffering capacity of the riparian zone tends to be more pronounced when water levels are higher (Pettit and Naiman 2007). Flooding during the wet season or after significant rains (e.g., after thunderstorms, hurricanes) has been shown to redistribute dead fuels (i.e., litter) by depositing them in clumps (Figure 3; Pettit and Naiman 2007). Clumped fuels lead to locally high-intensity fires when they burn during drier conditions. Therefore, managers should determine if burning is likely to reach clumped fuels and increase local fire intensity and severity in the riparian zone. In these cases, especially when riparian zones have longer fire-return intervals, firebreaks may be beneficial. Furthermore, the effects on plants and animals are often species-specific, with some responding positively and others negatively to fire. (See the first paragraph of the “Fire Impacts upon Wildlife” section and [Osborne, Kobziar, and Inglett 2013] for some specific examples). Managers must therefore consider buffering capacity and potential impacts to both fire-sensitive and fire-resilient species in each season, focusing in particular on water levels and fuel loading (Osborne, Kobziar, and Inglett 2013; Menges et al. 2017).

Credit: Raelene M. Crandall, UF/IFAS

As discussed in the vegetation section, prolonged drought increases the probability that wetlands will burn and hydrarch succession will be reversed. Utilizing prescribed fires during the dry season can be an effective management tool for this (Kuhry 1994; Kirkman 1995). Burning wetlands during the wet season doesn’t burn the accumulated organic matter even if the surface vegetation burns, though this may be preferable in many cases to avoid prolonged peat burning (Ewel 1995; Smith et al. 2001). Sometimes, though, wet-season fires can remove live vegetation from the wetland ecosystem without providing the benefits of reversing hydrarch succession (Just, Hohmann, and Hoffmann 2016). Even dry-season fires may not remove enough organic material from the wetland to reverse hydrarch succession. In some cases, extended drought conditions are required for a fire to burn down to the underlying mineral soil (Just et al. 2016). This could explain the infrequent charcoal layers in wetland soil core samples (Davis 1979). Wetlands can even have several decades to over a hundred years between recorded fires because the confluence of factors that facilitate a wetland fire don’t frequently align (Davis 1979).

Again, the biggest concern with using prescribed fire to burn wetlands is that when wetlands dry out enough to be burned, they tend to smolder and produce thick, acrid smoke that can reduce air quality and visibility on roadways (Watts et al. 2015). Furthermore, burning dry wetlands can have ecological consequences, such as releasing large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, killing large trees (Cypert 1961) or providing an opening for invasive species (Smith et al. 2001) Finally, wetland fires can burn for weeks or months (Watts et al. 2015).

In some cases, wetlands can be burned separately from the adjacent upland habitat when conditions are not favorable for a burn in the upland area. This strategy has its own set of potential drawbacks, however. Adding firebreaks can have unintentional and harmful consequences, such as isolating developing amphibians or encouraging woody encroachment (Ward et al. 2024). One strategy is to burn a wetland and adjacent upland habitat separately. Managers can burn the upland habitat first and the wetland shortly afterwards. This method typically requires specific management planning, goals, and flexibility but can be very helpful for protecting target species and maintaining a mosaic of fire regimes (Russell, Van Lear, and Guynn, Jr. 1999). Knowledge of the site’s current and past weather and fire history is essential for determining fire behavior, probability, and severity in riparian zones, particularly for wetlands. The atmospheric dispersion index and the Keetch-Byram drought index are especially important for planning and deciding if the timing is right (Keetch and Byram 1968; Lavdas 1986). Understanding the benefits and risks associated with riparian (and wetland) prescribed burns and how to apply fire to these ecosystems to align with management goals will help land managers make informed decisions.

The behavior of fire adjacent to a water body is influenced by the type of water body and topography of the riparian zone.

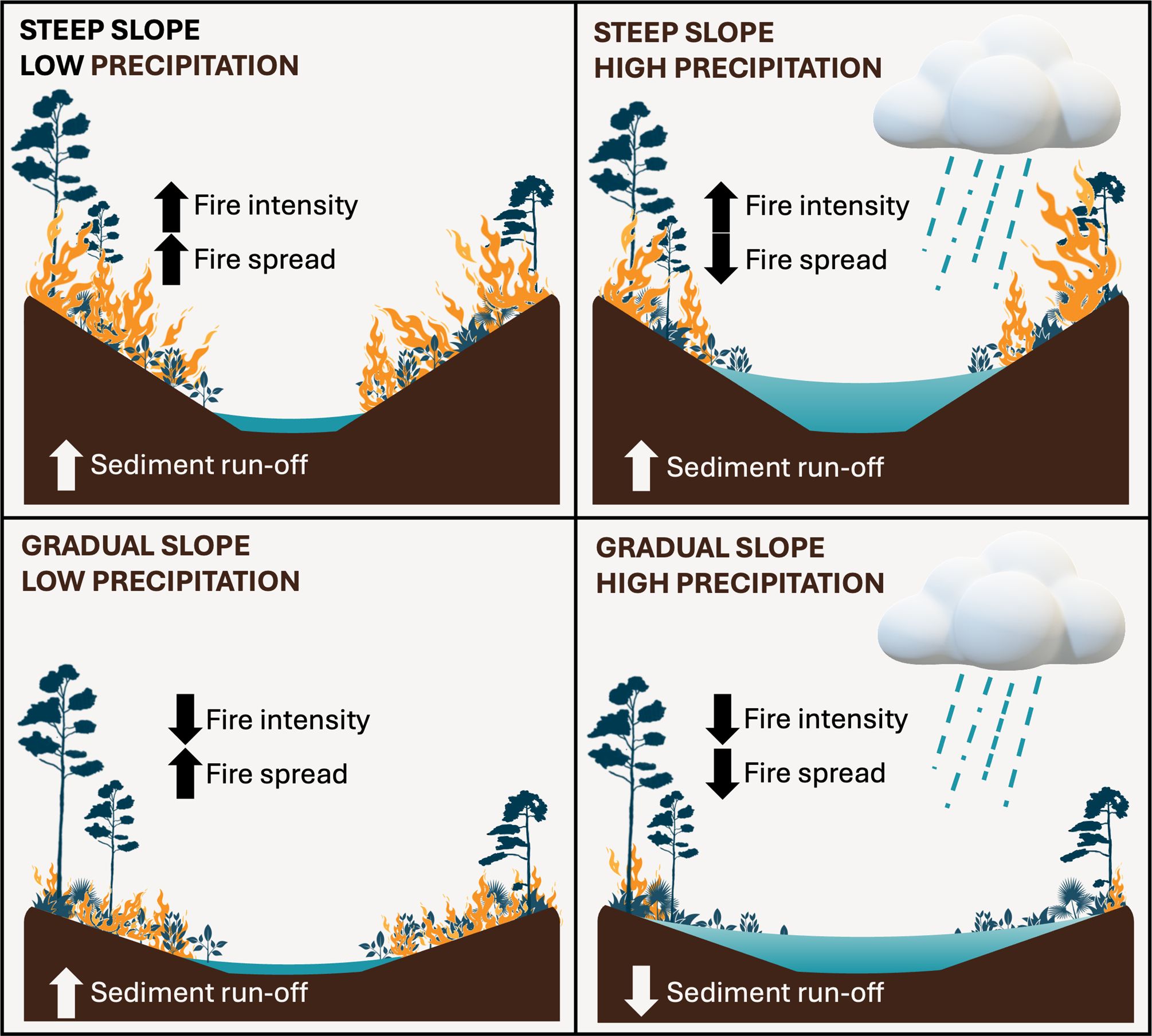

Stream riparian zones have been the focus of most US studies that examine fire effects, in large part because this habitat type dominates in western US landscapes with large elevation changes where high-severity fires have occurred (Dwire and Kauffman 2003; Bixby et al. 2015). Figure 4 and Pettit and Naiman (2007) outline how changes in elevation and rainfall in riparian zones change fire intensity and the spread of fires. Rapid changes in elevation lead to fire regimes similar to those of uplands. Steep gradients facilitate fire spread by increasing vegetation preheating and lowering the fuel moisture content. Fuel preheating can be further influenced by wind funneling through these areas. In contrast, riparian zones with gradual elevation changes tend to have longer fire-return intervals due to higher buffering capacity from higher fuel moisture content, though this trend is strongest when water levels are high (Figure 4). In Florida riparian zones, groundcover must be considered alongside elevation and water levels when predicting fire behavior. Herbaceous groundcover is more likely to burn than woody groundcover (Just, Hohmann, and Hoffmann 2016), but burning in the dry season can reduce woody vegetation encroachment, although reduction may require consistent burning for many years (Huffman and Blanchard 1991; Hess 2014) or mechanical removal before burning (Martin and Kirkman 2009).

Credit: Raelene M. Crandall, UF/IFAS

Furthermore, the riparian zones of springs, streams, rivers, lakes, ponds, and wetlands differ from one another and have differing fire-buffering capacities. For instance, the buffering of riparian zones next to flowing waters (streams, rivers, etc.) tends to increase as the wetted width of the stream or river increases, including when the adjacent floodplain is inundated (filled) with water. In Florida, these habitats include alluvial, blackwater, seepage, and spring-run streams/rivers (Box 2). In flowing waters, fire impacts extend downstream over time as networks of streams and rivers transport burned organic matter, sediments, and nutrients. In contrast, lakes and larger, non-ephemeral wetlands will have much longer water residence times, and thus, the burned organic matter, sediments, and nutrients after fires may persist in the adjacent habitat (McCullough et al. 2019). Post-fire sediment run-off will typically be lowest with a gradual slope and low-intensity fire, so this should be an additional consideration (Figure 4). The buffering capacities of pond, wetland, and lake riparian zones increase as water residence times increase and decrease as fire intensity/severity increases and with rapid elevation changes (McCullough et al. 2019). Across all types of water bodies, riparian zones of large water bodies act as a natural firebreak (Dwire and Kauffman 2003). Understanding variations in riparian zones and the influence of topography and fire history is imperative to ensure that prescribed fires are effective and safe relative to management goals and objectives.

An additional consideration for how fire behavior is influenced by topography for riparian zones of wetlands relates again to hydrarch succession. As wetlands fill with organic material, the gradual change in surface elevation is reduced, and the surrounding community can encroach on the wetland. Eventually, a bottomland forest or prairie can encroach, and the vegetation structure of the wetland will become more similar to that of its surroundings and less differentiated by hydroperiod and elevation (Kelley and Batson 1955; Kirkman 1995). The subsurface conditions of these wetlands are saturated, but the surface doesn’t flood. In this case, the organic matter that fills the wetland raises the surface level to that which surrounds the wetland. Water can be present below the surface, but the typical wetland plants that were there can’t survive once the hydroperiod has been drastically altered or reduced entirely (Kimura and Tsuyuzaki 2011). The seasonality and vegetation structure will strongly influence fire behavior, particularly if fire-sensitive species persist to reduce the likelihood of fires in and around the wetland (Just et al. 2016). Managers should consider how water body type, elevation changes, groundcover vegetation structure, and water levels will influence fire behavior when burning in riparian zones of Florida.

Finally, changes to land use and management strategies will impact fire behavior in the riparian zones. These changes will alter fire behavior due to fuels, weather and seasonality, and topography. For example, fire suppression can increase fuel loading, alter vegetation composition and structure (typically woody encroachment), and sometimes lead to disease and insect outbreaks (Pettit and Naiman 2007). Putting firebreaks in riparian zones may be beneficial to prevent peat fires (particularly for wetlands) but can negatively impact organisms that rely on riparian/wetland burning (Bishop and Haas 2005; Ward et al. 2024). Logging, road building, livestock grazing, urbanization, and agricultural and recreational development can also affect the riparian zone by altering the dominant vegetation, reducing its size, and decreasing its buffering capacity (Dwire and Kauffman 2003). Channel alterations, damming, and other aquatic habitat changes often shift the riparian vegetation with predictable impacts on fire, sometimes resulting in the complete exclusion of fire (Dwire and Kauffman 2003). One habitat type in particular that has suffered from human alterations is the alluvial floodplain. Historical data provide evidence of infrequent fires sustaining monodominant bamboo stands (canebrake) in these habitats (Gagnon 2009). However, restoring not only the habitat, but the natural disturbance regime can be complicated (Gagnon and Platt 2008), so further research would be beneficial in these areas. Other habitats are impacted by invasive species (Smith et al. 2001; Just, Hohmann, and Hoffmann 2017), where managers must determine if eradication is possible or if these species must be managed in the context of the ecosystem. To burn effectively in and around riparian zones, Florida land managers must have a thorough understanding of prior land use, habitat alterations, and current management goals.

Management Considerations Overview for Florida Riparian Zones

Prescribed fire is a common management tool for southeastern US ecosystems, particularly in Florida pine savannas. Factors that affect fires in riparian areas, including fuel loading and fuel moisture content, topography, and weather conditions, should guide management decisions. In contrast to western fires, southeastern pine savannas tend to have shorter fire-return intervals with less intense fires. Wetlands can be the exception, however, especially when hydrarch succession occurs, or when there is a mosaic of fire regimes. Managers should consider adjacent habitat types, fire frequency in the upland habitat, water levels in the aquatic habitat, and vegetation structure for riparian fires, particularly herbaceous vs. woody groundcover. This also applies to burning wetlands, but the likelihood of undesirable prolonged duff smoldering must be balanced with the natural fire regime and can often be used to limit woody encroachment. Other management practices (e.g., mechanical removal) may be necessary to meet objectives.

Riparian areas act as refuges for many animals seeking to escape fires, while fires in riparian zones can indirectly benefit some species. Riparian zones also harbor plant species that are not resilient to frequent fires. Managers should focus on target organisms and/or general groups alongside seasonality for conducting prescribed burns in riparian zones.

Managers should consider monitoring riparian zones and developing specific burn objectives for these areas as a mosaic within the larger upland pine savanna ecosystem (Ewel et al. 2001). Further studies are needed to fill knowledge gaps. For instance, more research is needed to document the direct and indirect effects of fire in riparian zones upon both plants and animals, particularly in highly altered systems or those with invasive species. When available, familiarity with all historical data on local ecosystems will best inform fire-management practices in Florida riparian zones.

Literature Cited

Allen, J. C., S. M. Krieger, J. R. Walters, and J. A. Collazo. 2006. “Associations of Breeding Birds With Fire-Influenced and Riparian–Upland Gradients in a Longleaf Pine Ecosystem.” The Auk 123 (4): 1110–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/123.4.1110

Baxter, C. V., K. D. Fausch, and W. C. Saunders. 2005. “Tangled Webs: Reciprocal Flows of Invertebrate Prey Link Streams and Riparian Zones.” Freshwater Biology 50 (2): 201–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2004.01328.x

Bishop, D. C., and C. A. Haas. 2005. “Burning Trends and Potential Negative Effects of Suppressing Wetland Fires on Flatwoods Salamanders.” Natural Areas Journal 25 (3): 290–94.

Bixby, R. J., S. D. Cooper, R. E. Gresswell, L. E. Brown, C. N. Dahm, and K. A. Dwire. 2015. “Fire Effects on Aquatic Ecosystems: An Assessment of the Current State of the Science.” Freshwater Science 34 (4): 1340–50. https://doi.org/10.1086/684073

Brenner, J., D. Wade, J. L. Schortemeyer, et al. 2014. “Chapter 9: Ecological Effects.” In Florida Certified Prescribed Burn Manager Training Manual, edited by John Saddler, 1–19. https://www.fdacs.gov/Forest-Wildfire/Wildland-Fire/Prescribed-Fire/Certified-Prescribed-Fire-Acreage

Chiodi, A. M., N. S. Larkin, and J. M. Varner. 2018. “An Analysis of Southeastern US Prescribed Burn Weather Windows: Seasonal Variability and El Niño Associations.” International Journal of Wildland Fire 27 (3): 176. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF17132

Clark, K. L., W. E. Heilman, N. S. Skowronski, et al. 2020. “Fire Behavior, Fuel Consumption, and Turbulence and Energy Exchange during Prescribed Fires in Pitch Pine Forests.” Atmosphere 11 (3): 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11030242

Cooper, S. D., H. M. Page, S. W. Wiseman, et al. 2015. “Physicochemical and Biological Responses of Streams to Wildfire Severity in Riparian Zones.” Freshwater Biology 60 (12): 2600–2619. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12523

Crandall, R. M., and W. J. Platt. 2012. “Habitat and Fire Heterogeneity Explain the Co-Occurrence of Congeneric Resprouter and Reseeder Hypericum Spp. along a Florida Pine Savanna Ecocline.” Plant Ecology 213 (10): 1643–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-012-0119-0

Cypert, E. 1961. “The Effects of Fires in the Okefenokee Swamp in 1954 and 1955.” The American Midland Naturalist 66 (2): 485–503. https://doi.org/10.2307/2423049

Davis, A. M. 1979. “Wetland Succession, Fire and the Pollen Record: A Midwestern Example.” American Midland Naturalist 102 (1): 86. https://doi.org/10.2307/2425069

Dwire, K. A., and J. B. Kauffman. 2003. “Fire and Riparian Ecosystems in Landscapes of the Western USA.” Forest Ecology and Management 178 (1–2): 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(03)00053-7

Ewel, K. C. 1995. “Fire in Cypress Swamps in the Southeastern United States.” Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings 19.

Ewel, K. C., C. Cressa, R. T. Kneib, et al. 2001. “Managing Critical Transition Zones.” Ecosystems 4 (5): 452–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-001-0106-0

Fairfax, E., and A. Whittle. 2020. “Smokey the Beaver: Beaver‐dammed Riparian Corridors Stay Green during Wildfire throughout the Western United States.” Ecological Applications 30 (8). https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2225

Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI). 2010. “Guide to the Natural Communities of Florida: 2010 Edition.” Tallahassee, FL: Florida Natural Areas Inventory.

Gagnon, P. R. 2009. “Fire in Floodplain Forests in the Southeastern USA: Insights from Disturbance Ecology of Native Bamboo.” Wetlands 29 (2): 520–26. https://doi.org/10.1672/08-50.1

Gagnon, P. R., and W. J. Platt. 2008. “Multiple Disturbances Accelerate Clonal Growth in a Potentially Monodominant Bamboo.” Ecology 89 (3): 612–18. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1255.1

Hess, C. A. 2014. “Restoration of Longleaf Pine in Slash Pine Plantations: Using Fire to Avoid the Landscape Trap.” Dissertation, Tallahassee, FL: Florida State University.

Hiers, J. K., J. J. O’Brien, J. M. Varner, et al. 2020. “Prescribed Fire Science: The Case for a Refined Research Agenda.” Fire Ecology 16 (1): 11, s42408-020-0070–0078. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-020-0070-8

Huffman, J. M., and S.W. Blanchard. 1991. “Changes in Woody Vegetation in Florida Dry Prairie and Wetlands during a Period of Fire Exclusion, and after Dry-Growing-Season Fire.” In Fire and the Environment: Ecological and Cultural Perspectives, edited by Stephen C. Nodvin and Thomas A. Waldrop, 75–83. Asheville, NC: Southeastern Forest Experiment Station.

Humphries, W. J., and M. A. Sisson. 2012. “Long Distance Migrations, Landscape Use, and Vulnerability to Prescribed Fire of the Gopher Frog (Lithobates capito).” Journal of Herpetology 46 (4): 665–70. https://doi.org/10.1670/11-124

Ilhardt, B. L., E. S. Verry, and B. J. Palik. 2000. “Defining Riparian Areas.” In Forestry and the Riparian Zone, edited by Robert G. Wagner and John M. Hagan, 7–13. Orono, Maine.

Johnson, E. A., and K. Miyanishi. 1995. “The Need for Consideration of Fire Behavior and Effects in Prescribed Burning.” Restoration Ecology 3 (4): 271–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-100X.1995.tb00094.x

Just, M. G., M. G. Hohmann, and W. A. Hoffmann. 2016. “Where Fire Stops: Vegetation Structure and Microclimate Influence Fire Spread along an Ecotonal Gradient.” Plant Ecology 217 (6): 631–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-015-0545-x

Just, M. G., M. G. Hohmann, and W. A. Hoffmann. 2017. “Invasibility of a Fire-Maintained Savanna–Wetland Gradient by Non-Native, Woody Plant Species.” Forest Ecology and Management 405 (December): 229–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.09.052

Keetch, J. J, and G. M. Byram. 1968. A Drought Index for Forest Fire Control. Research Paper SE-38. Asheville, NC: USDA Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station.

Kelley, W. R., and W. T. Batson. 1955. “Conspicuous Vegetational Zonation in a ‘Carolina Bay.’ Part VI.” In An Ecological Study of the Land Plants and Cold~blooded Vertebrates of the Savannah River Project Area. 244–48. Biology 1. University of South Carolina Publication Series III.

Kimura, H., and S. Tsuyuzaki. 2011. “Fire Severity Affects Vegetation and Seed Bank in a Wetland: Effects of Fire in Early Spring on Wetland.” Applied Vegetation Science 14 (3): 350–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-109X.2011.01126.x

Kirkman, L. K. 1995. “Impacts of Fire and Hydrological Regimes on Vegetation in Depression Wetlands of Southeastern USA.” In Fire in Wetlands: A Management Perspective, edited by Susan I. Cerulean and R. Todd Engstrom, 19:10–20. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station.

Kirkman, L. K., M. B. Drew, L. T. West, and E. R. Blood. 1998. “Ecotone Characterization between Upland Longleaf Pine/Wiregrass Stands and Seasonally-Ponded Isolated Wetlands.” Wetlands 18 (3): 346–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03161530

Kuhry, P. 1994. “The Role of Fire in the Development of Sphagnum-Dominated Peatlands in Western Boreal Canada.” Journal of Ecology 82 (4): 899. https://doi.org/10.2307/2261453

Lavdas, L. G. 1986. An Atmospheric Dispersion Index for Prescribed Burning. Research Paper SE-256. Macon, GA: USDA Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. https://doi.org/10.2737/SE-RP-256

Martin, K. L., and L. K. Kirkman. 2009. “Management of Ecological Thresholds to Re‐establish Disturbance‐maintained Herbaceous Wetlands of the South‐eastern USA.” Journal of Applied Ecology 46 (4): 906–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01659.x

McCullough, I. M., K. S. Cheruvelil, J.‐F. Lapierre, et al. 2019. “Do Lakes Feel the Burn? Ecological Consequences of Increasing Exposure of Lakes to Fire in the Continental United States.” Global Change Biology 25 (9): 2841–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14732

Menges, E. S., K. N. Main, R. L. Pickert, and K. Ewing. 2017. “Evaluating a Fire Management Plan for Fire Regime Goals in a Florida Landscape.” Natural Areas Journal 37 (2): 212–27. https://doi.org/10.3375/043.037.0210

Moseley, K. R., S. B. Castleberry, and S. H. Schweitzer. 2003. “Effects of Prescribed Fire on Herpetofauna in Bottomland Hardwood Forests.” Southeastern Naturalist 2 (4): 475–86. https://doi.org/10.1656/1528-7092(2003)002[0475:EOPFOH]2.0.CO;2

Naiman, R. J., and H. Décamps. 1997. “The Ecology of Interfaces: Riparian Zones.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 28 (1): 621–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.621

Osborne, T. Z., L. N. Kobziar, and P. W. Inglett. 2013. “Fire and Water: New Perspectives on Fire’s Role in Shaping Wetland Ecosystems.” Fire Ecology 9 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0901001

Pettit, N. E., and R. J. Naiman. 2007. “Fire in the Riparian Zone: Characteristics and Ecological Consequences.” Ecosystems 10 (5): 673–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-007-9048-5

Platt, W. J., S. L. Orzell, and M. G. Slocum. 2015. “Seasonality of Fire Weather Strongly Influences Fire Regimes in South Florida Savanna-Grassland Landscapes.” Edited by Ben Bond-Lamberty. PLoS ONE 10 (1): e0116952. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116952

Riis, T., M. Kelly-Quinn, F. C. Aguiar, et al. 2020. “Global Overview of Ecosystem Services Provided by Riparian Vegetation.” BioScience 70 (6): 501–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biaa041

Russell, K. R., D. H. Van Lear, and D. C. Guynn, Jr. 1999. “Prescribed Fire Effects on Herpetofauna: Review and Management Implications.” Wildlife Society Bulletin 27 (2): 374–84.

Smith, S. M., S. Newman, P. B. Garrett, and J. A. Leeds. 2001. “Differential Effects of Surface and Peat Fire on Soil Constituents in a Degraded Wetland of the Northern Florida Everglades.” Journal of Environmental Quality 30 (6): 1998–2005. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2001.1998

Steel, Z. L., B. Campos, W. F. Frick, R. Burnett, and H. D. Safford. 2019. “The Effects of Wildfire Severity and Pyrodiversity on Bat Occupancy and Diversity in Fire-Suppressed Forests.” Scientific Reports 9 (1): 16300. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52875-2

Stratman, M. R. 1998. “Habitat Use and Effects of Prescribed Fire on Black Bears in Northwestern Florida.” Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee.

Svejcar, T. 1997. “Riparian Zones: 1) What Are They and How Do They Work?” Rangelands 19 (4): 4–7.

Vaughan, M. C., D. L. Hagan, W. C. Bridges, M. B. Dickinson, and T. A. Coates. 2021. “How Do Fire Behavior and Fuel Consumption Vary between Dormant and Early Growing Season Prescribed Burns in the Southern Appalachian Mountains?” Fire Ecology 17 (1): 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-021-00108-1

Verkaik, I., M. Rieradevall, S. D. Cooper, J. M. Melack, T. L. Dudley, and N. Prat. 2013. “Fire as a Disturbance in Mediterranean Climate Streams.” Hydrobiologia 719 (1): 353–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-013-1463-3

Ward, B., B. Griffin, K. Robertson, and K. Sash. 2024. “Prescribed Fire Management of Ephemeral Wetlands of Southern Pine Communities for Amphibian Conservation.” Southern Fire Exchange.

Watts, A. C., C. A. Schmidt, D. L. McLaughlin, and D. A. Kaplan. 2015. “Hydrologic Implications of Smoldering Fires in Wetland Landscapes.” Freshwater Science 34 (4): 1394–1405. https://doi.org/10.1086/683484

Wheaton, J. 2018. Baugh Creek & Hailey Creek - 5 Weeks After Sharpe Fire. Photograph. Utah State University. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. https://photos.google.com/u/1/share/AF1QipOYNFRC5EiUWHd85zDOrzqBKL2gtsj1tH5rwpI5RvXLRnrrQRO_9IqHAXotjXiVXQ?key=QVNtYmRHWmhScXdNSEp4aFFhNURUUFhTazBRSEV3