Folate/folic acid is necessary throughout the entire lifespan, especially for women who can become pregnant because of its role in reducing the risk of birth defects (US Preventive Services Task Force 2017). This publication provides information about the folate/folic acid needs of women who can become pregnant, including sources and strategies for meeting the recommended intake to reduce the risk for birth defects.

What is folate/folic acid?

Folate and folic acid are used interchangeably, yet there is a difference. Folate is naturally found in foods, whereas folic acid is the vitamin’s man-made form added to certain foods and vitamin supplements. Folic acid is easier for the body to absorb compared to the natural form found in foods (Caudill 2010). Once absorbed, both forms of this vitamin are used for important body functions, including DNA synthesis. DNA is needed for making new cells to support growth and development during pregnancy and throughout the growing years. It is also needed for making new cells to replace skin, hair, blood, and other types of cells that are lost or damaged. For this reason, consuming enough folate is important for people of all ages.

What are the sources of folate/folic acid?

Fortified Foods

In 1998, the United States began fortifying certain foods with folic acid to help women who can become pregnant obtain the recommended amount of folic acid and reduce their risk of having a baby with a certain type of birth defect. These fortified foods include enriched breads, cereals, pasta, rice, white flour, corn masa flour, cornmeal, and foods made with these products, such as cookies, crackers, tortillas, and others. A quick way to spot a food fortified with folic acid is to look for the word "enriched" on the ingredients label.

Natural Sources

Folate is naturally found in certain fruits, vegetables, and legumes. While other foods may contain some folate, the amount is generally low.

Cooking methods and the length of cooking time can affect the folate content of foods. When preparing vegetables, methods such as steaming, microwaving, and stir frying are good choices to help preserve as much folate as possible. If vegetables are boiled, it is best to use a small amount of water and avoid overcooking. An exception to this is when cooking dry beans and peas like pinto, black, and navy beans. These foods need to be cooked in a large amount of water for a long time to improve digestibility, yet they still provide a valuable amount of folate.

Folic acid is easier to absorb compared to folate naturally present in foods. To account for this difference, the folate/folic acid content of foods is expressed as Dietary Folate Equivalents (NIH 2021). Table 1 lists the micrograms of Dietary Folate Equivalents (DFEs) in foods based on serving size and method of preparation.

Table 1. Examples of folate sources.

Why is folic acid important for women who can become pregnant?

Folic acid has been linked with a reduction in the risk for neural tube defects (NTD) (Czeizel 1998; Wolff et al. 2009; van Gool et al. 2018) and other birth defects such as congenital heart issues (Botto, Mulinare, and Erickson 2000, 2003; Czeizel, Vereczkey, and Szabo 2015; Jahanbin et al. 2018; van Beynum et al. 2010; Wondemagegn and Afework 2022).

What is a neural tube defect (NTD) and how does folic acid help to reduce NTD risk?

The neural tube is the structure that becomes the baby's brain, spinal cord, and spine, developing between the 17th and 30th day of pregnancy (NCBDDD and CDC 2003). Research has shown that the chance of having a baby with an NTD is 40%–80% lower in women who took a folic acid supplement before becoming pregnant and throughout the early months of pregnancy compared to those who did not (Berry et al. 1999; Czeizel 1998; Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition 2006; Wolff et al. 2009).

When should women who can become pregnant take folic acid to reduce NTD?

As almost half of pregnancies (45%) in the United States are unplanned (Finer & Zolna 2016), all women who can become pregnant are advised to consume 400 mcg of folic acid before they become pregnant and during the first three months of pregnancy (Viswanathan et al. 2017; US Preventive Services Task Force 2017). Women who are at a higher risk, such as those who previously had a baby with an NTD and women who have diabetes or take certain antiseizure medications (NCBDDD and CDC 2003), should talk with their doctor about the need for a higher level of folic acid.

How much folate/folic acid do women who are pregnant or breastfeeding need?

The recommended daily intake is 600 mcg DFE for pregnant women and 500 mcg DFE for breastfeeding women (NIH 2021). Taking a supplement that contains folic acid is an option for women who find it hard to meet these recommendations from food sources alone.

How can women of reproductive age make sure they get enough folic acid?

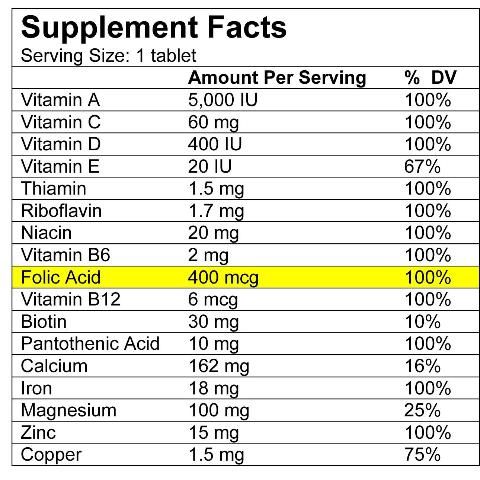

One way to ensure a woman is consuming adequate folic acid is through a supplement. Many multivitamins and multivitamin/multimineral supplements include folic acid along with other nutrients. Look at the Supplement Facts label (Figure 1) to find a brand that contains 400 mcg of folic acid. Some brands list the word "folate" on the label, others use "folic acid," but either term is okay if the supplement provides 400 mcg of folic acid.

Credit: Caroline Dunn

Women who may need more folic acid daily should talk with their doctor or registered dietitian nutritionist to learn the best way to get the right amount. Taking more than one multivitamin a day might result in consuming unsafe levels of other nutrients.

Another option is to take a supplement that only contains folic acid. These supplements are smaller than multivitamins, making them an appropriate choice for people who have trouble swallowing larger pills. They are also a low-cost way to get the recommended dose of folic acid compared to multivitamins. Select a brand (store or name brand) that contains 400 mcg of folic acid per pill and that is certified, as shown by the letters "USP" or "NSF" on the label.

It is important to take the supplement daily, so place them where they are easy to see such as next to the coffee pot, toothbrush, keys, or medications that are taken daily.

Is there an upper limit for folic acid?

Consuming too much folic acid, mainly through supplements, may mask deficiencies of other important vitamins or may have other risks. For this reason, the daily upper limit set for adults is 1000 mcg of folic acid (IOM, Food and Nutrition Board 1998). Only people informed by their healthcare provider to take more folic acid for medical reasons should need to exceed this limit. The upper limit does not apply to folate naturally found in foods.

Summary

Folate and folic acid are important for everyone, but especially for women of reproductive age. Women who can become pregnant are advised to consume 400 mcg of folic acid every day from supplements and/or fortified foods to help reduce the chance of having a baby with an NTD. Remember that not all pregnancies are planned, so all women who can become pregnant are advised to meet this recommendation.

Resources

National Council on Folic Acid—https://www.folicacidinfo.org

Florida Folic Acid Coalition—https://folicacidnow.net/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/index.html

US Department of Health and Human Services, Women's Health—https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/folic-acid

References

Berry R. J., Z. Li, J. D. Erickson, S. Li, C. A. Moore, H. Wang, J. Mulinare, et al. 1999. “Prevention of Neural-Tube Defects with Folic Acid in China.” China-U.S. Collaborative Project for Neural Tube Defect Prevention. The New England Journal of Medicine 341 (20): 1485–1490. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199911113412001

Botto, L. D., J. Mulinare, and J. D. Erickson. 2000. “Occurrence of Congenital Heart Defects in Relation to Maternal Multivitamin Use.” American Journal of Epidemiology 151 (9): 878–884. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010291

Botto, L. D., J. Mulinare, and J. D. Erickson. 2003. “Do multivitamin or folic acid supplements reduce the risk for congenital heart defects? Evidence and gaps.” American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 121A (2): 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.20132

Caudill, M. A. 2010. “Folate Bioavailablity: Implications for Establishing Dietary Recommendations and Optimizing Status.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 91 (5): 1455S–1460S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.28674E

Czeizel, A. E. 1998. “Periconceptional Folic Acid Containing Multivitamin Supplementation.” European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 78 (2): 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-2115(98)00061-X

Czeizel A.E., A. Vereczkey, and I. Szabo. 2015. “Folic Acid in Pregnant Women Associated with Reduced Prevalence of Severe Congenital Heart Defects in their Children: A National Population-based Case-control Study.” European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 193: 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.06.024

Fabbri, A.D.T., and G. A. Crosby. 2016. “A Review of the Impact of Preparation and Cooking on the Nutritional Quality of Vegetables Legumes.” International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 3: 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2015.11.001

Finer, L. B., and M. R. Zolna. 2016. “Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011.” New England Journal of Medicine 374 (9): 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1506575

Institute of Medicine (IOM), Food and Nutrition Board. 1998. Dietary Reference Intakes: Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jahanbin A., E. Shadkam, H. H. Miri, A. S. Shirazi, and M. Abtahi. 2018. “Maternal Folic Acid Supplementation and the Risk of Oral Clefts in Offspring.” The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 29 (6): e534–e541. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000004488

National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2003. Folic Acid Now. Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/60500/cdc_60500_DS1.pdf

National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2021. “Folate: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals.” Dietary Supplement Fact Sheets. Retrieved from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Folate-HealthProfessional/.

Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. 2006. “Folate and Disease Prevention.” London: The Stationary Office. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7e370a40f0b62305b818a9/SACN_Folate_and_Disease_Prevention_Report.pdf

US Preventive Services Task Force. 2017. “Folic Acid Supplementation for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.” JAMA 317 (2): 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19438

van Beynum, I. M., L. Kapusta, M. K. Bakker, M. den Heijer, H. J. Blom, and H. E. de Walle. 2010. “Protective Effect of Periconceptional Folic Acid Supplements on the Risk of Congenital Heart Defects: A Registry-based Case-control Study in the Northern Netherlands.” European Heart Journal 31 (4): 464–471. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp479

van Gool, J. D., H. Hirche, H. Lax, L. De Schaepdrijver. 2018. “Folic Acid and Primary Prevention of Neural Tube Defects: A Review.” Reproductive Toxicology 80: 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2018.05.004

Viswanathan, M, K. A. Treiman, J. Kish-Doto, J. C. Middleton, E. J. Coker-Schwimmer, and W. K. Nicholson. 2017. “Folic Acid Supplementation for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects: An Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force.” JAMA 317 (2): 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19193

Wolff, T., C. T. Witkop, T. Miller, and S. B. Syed. 2009. “Folic Acid Supplementation for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects: An Update of the Evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force.” Annals of Internal Medicine 150 (9): 632–639. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00010

Wondemagegn, A. T., and M. Afework. 2022. “The Association between Folic Acid Supplementation and Congenital Heart Defects: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” SAGE Open Medicine 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121221081069