There are many peach diseases that can affect fruit quality and the marketability of the produce. Blemishes to the skin or within the flesh can be a reason to reject an entire fruit load or significantly reduce the purchasing price.

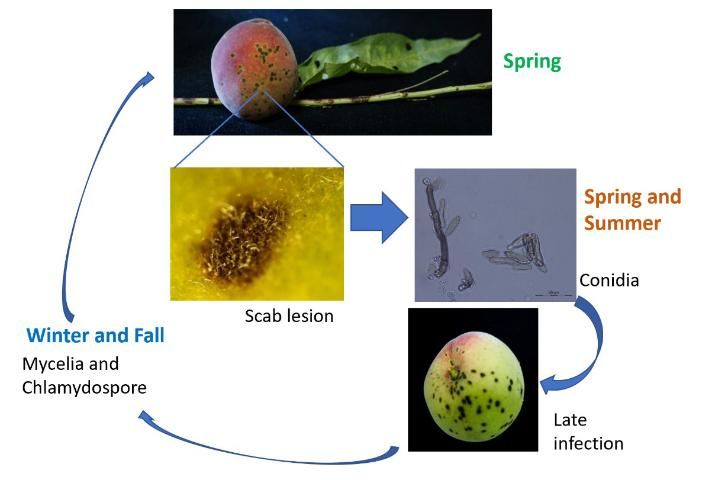

Peach scab is a disease caused by the fungus Cladosporium carpophilum (Figure 1). The pathogen can infect twigs, leaves, and fruits, where it can cause lesions that can affect fruit quality, marketability, and in extreme cases can cause cracking of the fruit and premature fruit drop. Peach scab is typical during periods of humid weather because rain splashes the conidia (asexual spores) from the fungus between leaves, twigs, and fruit in the tree canopy, which spreads the disease. This pathogen can infect other fruits and nuts within the Prunus species, like almonds, apricots, nectarines, and plums.

Credit: M. Olmstead, UF/IFAS

Shoot/Leaf Symptoms

Since spores of peach scab overwinter in raised lesions on shoots and bark, scouting for symptoms during the winter pruning process can help to determine disease management options. Infection in young, green shoots commonly begins with small, slightly raised, reddish-grey oval or circular lesions approximately 0.08 in (2 mm) in diameter. As shoots mature, the lesions expand to 0.1–0.3 in. (3–8 mm) and develop dark brown borders (Figure 2).

Credit: C. Mancero

Fruit Symptoms

Peach scab causes sunken lesions on the skin of fruit (Figure 3). When disease pressure is high, small lesions become noticeable on the young, green fruit. As the fruit mature, these small lesions grow and begin to produce conidia and conidiophore. Large, dark lesions can be found on mature fruit (Figure 4). Older lesions are grey to olive in color, circular, and well-defined. At this stage, lesions are approximately 0.7–0.2 in (2–5 mm) in diameter and a yellowish halo may surround the dark lesions in fruit with a significant blush. In nectarines, peach scab lesions may appear pale green with a dark center.

Credit: C. Mancero

Credit: C. Mancero

Peach scab lesions should not be confused with raised scabs often caused by shot-hole disease (Wilsonomyces carpophilus; http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/r602100711.html). Purple margins with light tan centers differentiate shot hole lesions from those caused by peach scab.

The corky cell layer beneath peach scab lesions does not expand as the fruit grows (Figure 4). This causes cracks in the skin that can extend into the peach flesh, generating an entry point for secondary pathogens such as fruit rot organisms or fruit flies. Often, the peach scab is found around the stem end of the fruit because of poor spray penetration into the canopy (Figures 4 and 5). Peaches are most susceptible during the shuck-split stage of growth, while nectarines are most susceptible 1–2 weeks after petal fall. While the fruit is most susceptible at early developmental stages, disease management is essential from fruit set to harvest to prevent significant skin damage.

Credit: C. Mancero

Disease Cycle

Peach scab can overwinter as mycelia (filamentous part of the fungi) in lesions or as chlamydospores (large, thick-walled structures) on vegetative tissue or in the bark of 1-year-old shoots. Chlamydospores are the primary source of inoculum in an orchard. During the spring and summer, conidia are produced when relative humidity is at least 100% for 24 hours, and temperatures exceed 60°F (16°C). The conidia (spores) are spread by wind or by rain splash. They can also be spread by irrigation systems such as those used for overhead frost protection during the early spring. Wind dispersal is relatively minor compared to rain/irrigation splash, the major means by which fungal spores are spread.

In the southeastern United States, the highest risk for infection occurs between petal fall and shuck split. (For more information on peach phenological stages, see https://www.clemson.edu/extension/peach/commercial/diseases/files/h2.pdf.) Because they lack fuzz, nectarine fruit can be infected earlier than peaches, so monitoring should begin earlier in the fruit development. In some parts of the southeastern United States, late infections are not of concern because of the extended incubation period between infection and the appearance of symptoms (40–70 days); however, late infection remains a concern in Florida, where many of the low-chill peach varieties grown have a fruit developmental period of 70–90 days. (For more information, see https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg374.)

During spring seasons with frequent precipitation, spray intervals should be shortened, and fungicides should be rotated to avoid development of fungicide resistance. Current and historical weather data can be found for various statewide sites using the Florida Automated Weather Network (FAWN; http://fawn.ifas.ufl.edu/). A rainy spring season (compared to the long-term average for your location) will most likely prolong the period of fungicide application for peach scab.

Credit: C. Mancero

Management

Planning during the orchard establishment phase should include proper site selection. Avoid low-lying areas with poor air circulation and soil drainage. Implementation of a monitoring program based on the presence of lesions on the bark (Figure 1) of the previous years' growth can help to determine the relative potential for infection in the current year. Lesion numbers and sizes can be monitored while pruning and fruit thinning. Furthermore, inoculum sources can be reduced by removing wild or neglected stone-fruit trees growing nearby.

To date, there are no varieties that are resistant to peach scab. Cultural controls are limited to ensuring that proper pruning practices keep the tree canopy open in order to facilitate fungicide spray penetration. Fungicide sprays must be applied just before peak infection periods to provide maximum protection on developing fruit. The first infection period occurs at petal fall, followed by additional infection periods at shuck split, shuck off, and cover sprays as fruit are developing (Table 1). Targeted sprays work well. They will be most effective during periods of high conidial production, from shuck split to 8 weeks after petal fall (Table 2). Fungicide sprays act as a preventive technique; they do not eliminate scab inoculum from the field.

Tables

Suggested fungicide options organized by efficacy for peach scab management during key phenological stages, their Fungicide Resistance Action Committee codes (FRAC codes), application rates, effectiveness, re-entry intervals (REI) and pre-harvest intervals (PHI). Adapted from the Southeastern Peach, Nectarine, and Plum Management Guide*. Effectiveness is gauged from (+++++) = Excellent to (+) = Poor.