Introduction

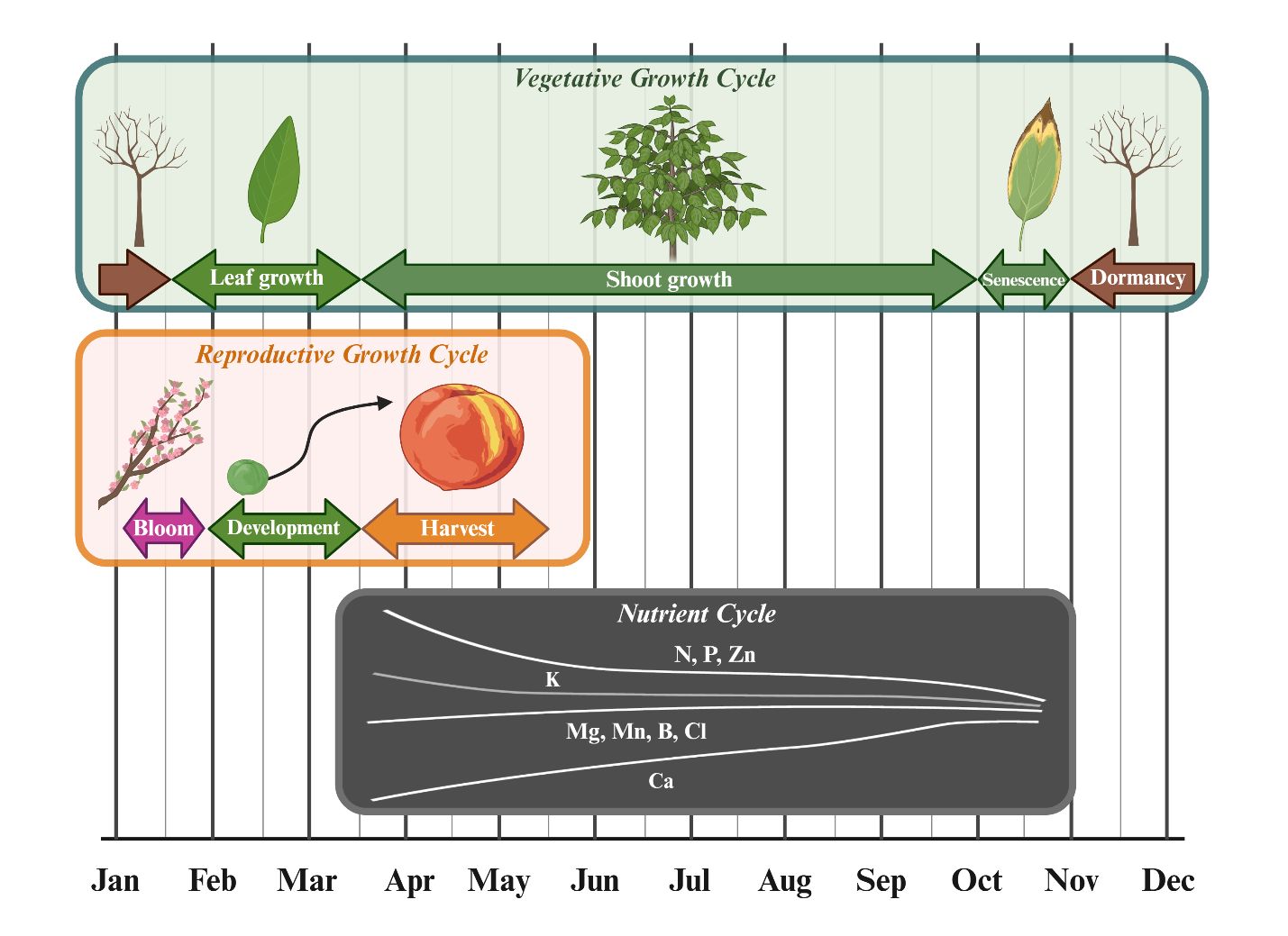

Appropriate nutrient management is critical for ensuring healthy vegetative and reproductive growth in perennial fruit tree species, such as peaches, as these developmental processes demand substantial amounts of resources (Figure 1). Consequently, adequate fertilization management practices at all stages of peach development are essential to obtain high yields and optimal fruit quality. Fertilization practices are also important economically since they represent an important portion of the costs associated with peach production.

Improper fertilization can have negative agronomic and environmental consequences. Over-fertilization may increase salinity, cause nutrient imbalances, and contribute to nitrate and phosphate contamination of surface water and groundwater. (For more information, refer to EDIS publication FOR371, “Water Quality in the Floridan Aquifer Region.”) Conversely, under-fertilization can limit tree growth and negatively affect fruit yield, size, and quality, ultimately reducing profitability for growers.

Peach production is a dynamic process that requires an understanding of the changing nutritional demands of the orchard throughout the growing season. This publication provides an overview of general fertilization management practices for low-chill peach trees grown in Florida’s subtropical climate. Its goal is to support county Extension agents, Extension faculty, growers, and homeowners with general and practical guidelines for optimizing nutrient management in peach orchards.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Peach Growing Season

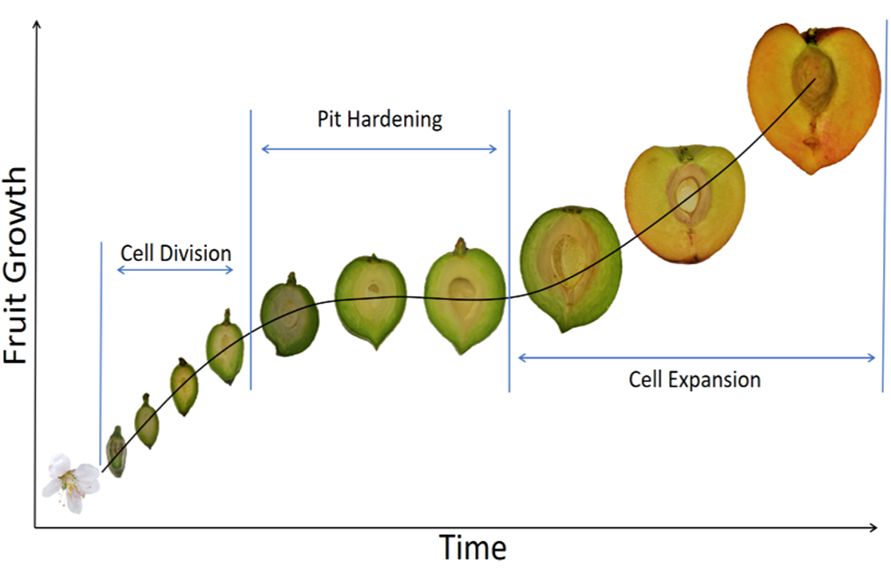

The plant growth cycle is different for peach trees grown in subtropical regions, such as Florida, compared with peaches grown under temperate regions in northern states or in Mediterranean-type regions, such as California. These climatic differences are critical to determining appropriate management practices, such as fertilization, irrigation, and pruning. The vegetative growth cycle for low-chill peaches in Florida is divided into four phases (Figure 2): dormancy, from early November until mid-January; leaf development, from mid-January to mid-March; shoot development, from mid-March to late October; and leaf senescence, from late October to late December. On the other hand, the reproductive growth cycle starts with full bloom by mid-January and continues with fruit development and maturation, lasting approximately 80 days. The fruit development phase includes an initial period of quick growth, caused by a high rate of cell division occurring in the fruit. Then, growth slows and fruit transition to the pit hardening phase (Figure 3). Lastly, a period of cell expansion allows fruits to reach their final size and harvest maturity generally by the end of March.

Credit: Created in BioRender. Clavijo-Herrera, J. (2024) https://BioRender.com/u56s131. Adapted from Layne and Bassi (2008).

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Variations in the timing of the vegetative and reproductive phases may occur depending on the cultivar and the specific temperature regime of the location and season, with warmer temperatures shortening and cooler temperatures prolonging the time required for maturity. It is important to mention that the flowering period in Florida is long, which is why flowers, fruit set, and fruitlets can grow at the same time in a tree. From mid-March to mid-May, fruit ripen and can be harvested.

Peaches are deciduous trees that enter a dormant period during winter. To “break” dormancy and produce flowers, peach trees require a certain period of time under low temperatures, which is commonly known as the chilling accumulation period. “Chilling hours” are one-hour periods of temperatures between 32°F and 45°F. Peaches suggested for production in Florida are known as “low-chill” peaches and require less than 200 chilling hours. (For more information, refer to EDIS publication Cir1159, “Florida Peach and Nectarine Varieties.”) A short dormancy period and an early harvest season are two key characteristics for peach production to be economically viable in our state. This early market window makes it possible to access markets before northern states initiate harvesting.

Chilling accumulation in Florida begins by the last week of October and ends by March. In central Florida, peach trees should accumulate sufficient chilling from December until mid-January to ensure successful commercial production and to meet the unique market window, which is from the end of March until the first week of May. If accumulated after mid-January, chilling is late and considered not useful for commercial production. Although northern regions of the state accumulate chilling faster than southern regions, Florida peaches must reach full bloom by the third week of January to access the profitable, early market window. The fruit developmental period (occurring between fruit set and fruit maturity) can vary from one cultivar to another and can take as few as 60 days; however, the ripening phase for low-chill peach cultivars in Florida generally occurs between mid-March and May.

In perennial species, vegetative and reproductive growth usually occur simultaneously, thus competing for resources. Some studies have shown that fruit presence can reduce stem and leaf growth before and after harvest. This highlights the importance of thinning and fertilization, not only to obtain good fruit size and quality but also to ensure appropriate vegetative growth that will sustain the following year’s crop. Low-chill peach trees growing under Florida conditions can become vigorous and large. They have a short period of winter rest and a long growing season after the fruit harvesting period in May, extending up to 200 days. Therefore, this high vigor of low-chill cultivars makes it necessary to prune them during summer, generally right after harvest, to control tree size. Finally, leaves harden off starting in October as shortening days and decreasing temperatures stimulate the entrance into dormancy. However, such stimuli are not enough for Florida peaches to fully defoliate naturally, so zinc sulfate spray applications are suggested in late November at a rate of 10% to 15% to ensure complete defoliation. Leaves must be absent from peach trees for buds to accumulate enough chilling required to overcome dormancy.

Adequate plant nutrition is essential for maintaining healthy and productive peach orchards. However, tree growth and development are dynamic processes that change throughout the growing season. As a result, nutrient demand and concentration in leaves vary across the different stages of the season.

Seasonal Variability in Leaf Nutrient Concentration

Researchers in Florida studying the low-chill peach scion ‘UFSun’ observed seasonal trends in foliar nutrient concentrations. Nitrogen (N) concentration in leaves was highest in spring, declined through summer, stabilized in fall, and decreased toward the end of the growing season as a result of nutrient mobilization to storage structures such as roots and the trunk. Potassium (K), which is as highly soluble and mobile as nitrate, followed a similar trend, although its concentration increased during fall. Phosphorus (P) concentration was high at the beginning of the growing season, declined during spring and summer, and gradually increased toward the end of the season. In contrast, magnesium (Mg), sulfur (S), and iron (Fe) remained relatively stable, although S decreased in summer and Fe increased in fall. Calcium (Ca) concentration increased steadily throughout the growing season but declined near the end. Boron (B) and manganese (Mn) were stable during spring and summer, increased in fall, and decreased by the end of the season. Zinc (Zn) was highest at the beginning of the growing season, declined through fall, and partially recovered toward the end of the growing season. Finally, copper (Cu) remained mostly stable but had a tendency to increase during summer and fall.

As noted, several nutrients maintain relatively stable concentrations during the growing season. However, the demand for certain nutrients increases during specific physiological stages, such as the fruit development process or vegetative flushes. Therefore, nutrient applications should align with the timing of these critical periods. Harvest time can be used as a reference point to organize the nutrient management plan. A common and effective strategy is to apply approximately half of the required nutrients before harvest and the remaining half afterward. Additionally, further splitting these applications into smaller, well-timed portions can enhance nutrient use efficiency and support optimal tree performance.

General Fertilizer Application Guidelines for Peach Orchards in Florida

Initially, it is suggested to make the necessary soil amendments before planting, based on the results of the soil report. Ideally, the soil pH for producing stone fruits should be between 6.0 and 6.5. Many regions in Florida have acidic soils with pH ranges below 6.0, so applications of lime can help raise the soil pH when needed. For sandy soils, fertilizers should contain a lower proportion of P and K compared to N. Avoiding the use of calcium nitrate during the rainy season is suggested to prevent potential N leaching. Even P and K are prone to leaching in sandy soils, so split applications of those nutrients are also suggested.

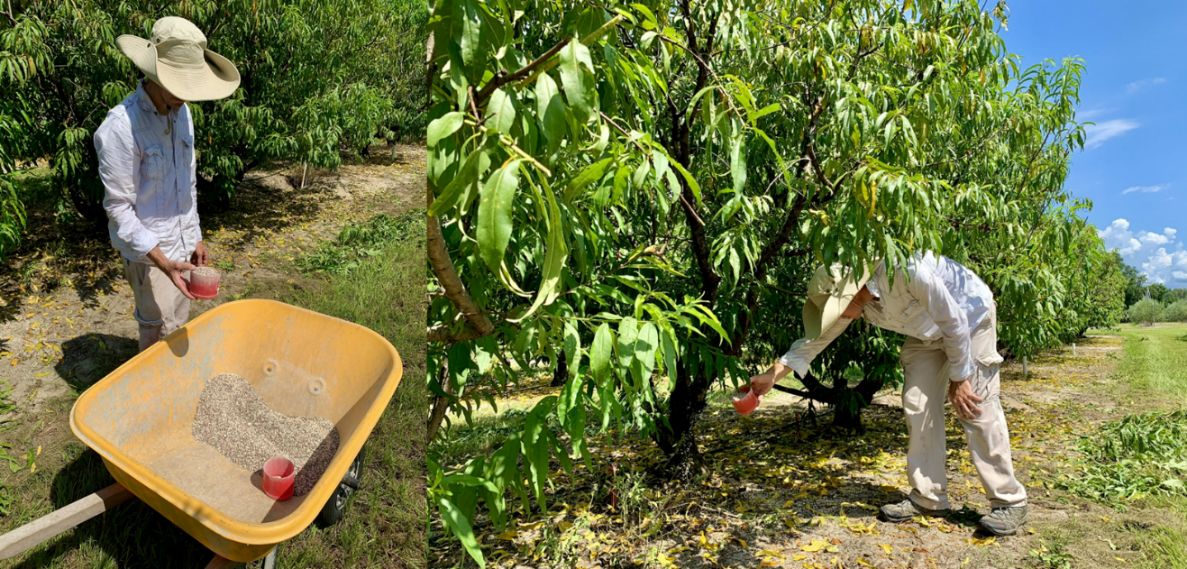

Providing macronutrients as soil applications (Figure 4) is suggested unless absorption problems are detected or amendments are required. Nitrogen applications are critical for any commercial orchard to ensure successful production. However, excessive N fertilization can generate excessive vegetative growth, which may block sunlight from reaching fruits inside the canopy, reducing the development of red coloration on the peel. Excessive N fertilization may also increase pruning costs. Additionally, pest and disease pressures tend to be greater when vegetative growth is excessive. Overall, 90 lb N per acre per year is suggested. For peaches growing in subtropical regions, four split applications are encouraged according to the phenological stages of the plant. In bearing orchards, it is suggested to apply N by the time fruit growth and development initiate. Approximately half of the total N to be applied should be enough to satisfy the demand of developing fruit, so the first application should be done by the end of January and the second by the end of March. Applications after harvest are also critical to ensure that trees will have enough vegetative growth to sustain the following year’s crop. The remaining half of the total N application should be provided after harvest. A third application immediately after harvest in May/June and a fourth application in August during summer, by the time of the second flush, are suggested. The application of most macronutrients can follow this schedule to maximize fertilizer use efficiency in the orchard. Direct soil micronutrient fertilization is not usually required when utilizing fertilizer macronutrient blends that already contain micronutrient elements.

Credit: Jonathan Clavijo-Herrera, UF/IFAS

Phosphorus applications are particularly important at planting time since this nutrient stimulates root development. Only a few cases of P deficiency have been reported in mature peach orchards, although performing P applications is suggested as a standard management practice, considering the low P mobility in the soil. The phosphorus application suggestion for peaches is around 20 to 40 lb P/acre per year, if required by the plant tissue and soil reports. Phosphorus applications after harvest are important for peaches to accumulate reserves for the following season.

Potassium demand for fruit growth is high, so K fertilization at early stages of fruit development is important. The sandy soils of Florida are characterized by reduced nutrient and water-holding capacity, so split K applications during the growing season are important to satisfy peach demands. Applications of up to 140 lb K/acre per year are suggested for productive peach orchards. Excessive K applications can lead to cation imbalances in the soil and reduce the uptake of other nutrients, such as Ca and Mg. On the other hand, peach trees recycle only 30% of the K content from leaves before senescence.

The accumulation of Ca by fruits mostly occurs in the initial stage of fruit development, so it is important to provide this nutrient during or before early fruit development. Although Ca deficiency is uncommon in peach orchards, foliar applications are suggested to supply this nutrient if needed. On the other hand, Mg deficiency might be observed in regions with highly acidic sandy soils that are exposed to excessive rainfall or irrigation. In general, Mg deficiency issues are uncommon in peach-growing regions, but it has been reported in citrus groves in Florida. (For more information, refer to EDIS publication SL403, “Manganese (Mn) and Zinc (Zn) for Citrus Trees.”) Additionally, plants can obtain S from different sources, such as sulfur-containing fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation water. Consequently, S fertilization is not usually required.

Micronutrient application via foliar sprays provides rapidly available micronutrients to plants when needed and is considered a cost-effective alternative. Zinc deficiencies have been reported in citrus and other crops in Florida as a result of the sandy texture and low organic matter content of soils in the state. Soil applications of Zn can be performed, although the application rates are high. Foliar applications are the suggested strategy for Zn amendments. Although Zn is not considered mobile in plants, Zn movement from leaves to roots during fall has been reported in peaches. Moreover, applications of zinc sulfate (10% to 20%) can defoliate trees in the fall, helping peach trees enter dormancy, which will also help alleviate any potential Zn deficiency in the following season.

Foliar applications of B before blooming and after harvest contribute to improving fruit set rates. Although generally considered a low-mobility nutrient, B tends to behave as a mobile element in plant species with high sorbitol content, such as peaches, pears, and apples; consequently, foliar applications of B are effective in peach orchards. However, excessive B applications may easily lead to toxicity. On the other hand, Fe deficiency issues can be solved easily by soil application of chelated Fe. Chelated micronutrients are generally more effective sources than traditional salts. Foliar applications of Mn at the beginning of the growing season are suggested if deficiency symptoms have been observed in the orchard. Copper is usually present in fungicides and other pesticides, so additional Cu fertilization is not typically required in orchards following appropriate pest management practices.

Since low-chill peaches grown in subtropical regions exhibit phenological stages that differ in timing from peaches produced in temperate regions, it is important to account for these differences when adapting fertilization practices to the specific needs of peach orchards in Florida. Information obtained from plant tissue and soil analyses is essential for developing effective nutrient management programs, and growers are strongly encouraged to use these reports as a foundation for fertilization planning. In general, macronutrient applications (particularly N, P, and K) should be applied in split soil applications: half at the beginning of the growing season and half after harvest. Further dividing the postharvest application, applying one portion immediately after harvest and another around the time of the second vegetative flush in August, may enhance nutrient uptake and tree performance under Florida conditions. Micronutrient deficiencies, on the other hand, are typically addressed through foliar applications. These should be applied based on symptoms and confirmed through foliar analysis to ensure appropriate and timely intervention.

Fertilizer Rate Guidelines for Young and Bearing Peach Trees

Considering the age of the plants in the orchard is important for proper nutrient management. For newly established orchards, the following tables specify the fertilization rates and timing of macronutrients when producing trees in the first year (Table 1), second year (Table 2), and third year (Table 3), as well as mature trees in the fourth year and beyond (Table 4). Using fertilizer blends that contain micronutrient elements is suggested to avoid potential micronutrient deficiencies.

Table 1. First-year fertilization suggestions for newly established orchards in sandy soil using N-P-K (12-4-8) fertilizer plus micronutrients (Source: UF/IFAS 2019).

Table 2. Second-year fertilization suggestions for producing orchards in sandy soil using N-P-K (12-4-8) fertilizer plus micronutrients (Source: UF/IFAS 2019).

Table 3. Suggested fertilizer applications for Year 3 in producing orchards in sandy soil using N-P-K (12-4-8) fertilizer plus micronutrients (Source: UF/IFAS 2019).

Table 4. Suggested fertilizer applications for mature trees in sandy soil using N-P-K (12-4-8) fertilizer plus micronutrients (years 4+) in producing orchards (Source: UF/IFAS 2019).

Conclusion

Appropriate nutrient management is essential for the successful production of low-chill peaches in Florida’s subtropical climate. It contributes to securing peach tree growth, orchard health, and fruit quality. The fruit development period and vegetative flushes are particularly demanding stages that require a sufficient and timely supply of nutrients to ensure orchard productivity. Consequently, fertilization practices should carefully align with the tree’s vegetative and reproductive development cycles. In this regard, splitting nutrient applications can enhance nutrient use efficiency, reduce leaching losses, and support sustained orchard productivity. Additionally, foliar applications offer a practical solution for addressing deficiencies, particularly for micronutrients, although making decisions based on annual plant tissue and soil analyses is highly suggested. These guidelines provide a general framework to optimize nutrient management and support the long-term sustainability of peach orchards in the state.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the FDACS Specialty Crops Block Grant (SCBGP) and Fertilizer Rate and Nutrient Management Programs.

References

Layne, D. R., and D. Bassi, eds. 2008. The Peach: Botany, Production and Uses. CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845933869.0000

UF/IFAS. 2019. "Stone Fruit Nutrition.” Department of Horticultural Sciences. Last modified May 9, 2019. https://hos.ifas.ufl.edu/stonefruit/production/nutrition/

Further Reading

AgroClimate. n.d. "Chill Hours Calculator." Accessed September 8, 2025. http://agroclimate.org/tools/chill-hours-calculator/

Batjer, L. P., and M. N. Westwood. 1958. "Seasonal Trend of Several Nutrient Elements in Leaves and Fruits of Elberta Peach." Proceedings of the American Society for Horticultural Science 71: 116–126.

California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA). n.d. "California Fertilization Guidelines—Peach and Nectarine." Accessed September 8, 2025. https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/is/ffldrs/frep/FertilizationGuidelines/Peach_Nectarine.html

Grossman, Y. L., and T. M. Dejong. 1995. "Maximum Vegetative Growth Potential and Seasonal Patterns of Resource Dynamics During Peach Growth.” Annals of Botany 76 (5): 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1995.1122

Haifa. n.d. “Fertilization of Peach Trees: A Comprehensive Recommendation.” Accessed September 8, 2025. https://www.haifa-group.com/fertilization-peach-trees-comprehensive-recommendation-0

Mounzer, O. H., W. Conejero, E. Nicolás, et al. 2008. “Growth Pattern and Phenological Stages of Early-Maturing Peach Trees Under a Mediterranean Climate.” HortScience 43 (6): 1813–1818. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.43.6.1813

Olmstead, M., and K. Morgan. 2013. “Orchard Establishment Budget for Peaches and Nectarines in Florida: HS1223, 7/2013.” EDIS 2013 (7). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1223-2013

Rubio Ames, Z., J. K. Brecht, and M. A. Olmstead. 2020. “Nitrogen Fertilization Rates in a Subtropical Peach Orchard: Effects on Tree Vigor and Fruit Quality.” Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 100 (2): 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.10031

Sallato, B. 2021. “Fall Nutrient Sprays in Tree Fruit." Publication No. FS365E. Washington State University Extension. https://pubs.extension.wsu.edu/product/fall-nutrient-sprays-in-tree-fruit/

Sanz, M. 2000. "Evaluation of DRIS and DOP Systems Along Growing Season of the Peach Tree.” ITEA 96 (1): 7–18. https://www.aida-itea.org/index.php/revista/contenidos?idArt=544&lang=eng

Sarkhosh, A., M. Olmstead, J. Chaparro, P. Andersen, and J. Williamson. 2018. “Florida Peach and Nectarine Varieties: Cir1159/MG374, rev. 10/2018.” EDIS 2018 (September). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-mg374-2018

Shahkoomahally, S., J. X. Chaparro, T. G. Beckman, and A. Sarkhosh. 2020. “Influence of Rootstocks on Leaf Mineral Content in the Subtropical Peach cv. UFSun.” HortScience 55 (4): 496–502. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI14626-19

Singerman, A., M. Burani-Arouca, and M. Olmstead. 2017. “Establishment and Production Costs for Peach Orchards in Florida: Enterprise Budget and Profitability Analysis: FE1016, 7/2017.” EDIS 2017 (4). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fe1016-2017

Soria Baráibar, J. 2014. Manual del duraznero: La planta y la cosecha. Boletin de divulgación INIA: 108. Instituto Nacionel de Investigación Agropecuaria.

Souza, F., E. Alves, R. Pio, et al. 2019. “Influence of Temperature on the Development of Peach Fruit in a Subtropical Climate Region.” Agronomy 9 (1): 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9010020

Souza, F. B. M. de, R. Pio, J. P. R. A. D. Barbosa, G. L. Reighard, M. H. Tadeu, and P. N. Curi. 2017. “Adaptability and Stability of Reproductive and Vegetative Phases of Peach Trees in Subtropical Climate.” Acta Scientarium Agronomy 39 (4): 427–435. https://doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v39i4.32914

U. S. Department of Agriculture, National Agriculture Statistics Service (USDA-NASS). 2024. “Quick Stats Tools.” Last modified February 28, 2024. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/

Zambrano-Vaca, C., L. Zotarelli, R. C. Beeson, et al. 2020. “Determining Water Requirements for Young Peach Trees in a Humid Subtropical Climate.” Agricultural Water Management 233: 106102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106102

Zotarelli, L., C. Zambrano-Vaca, C. E. Barrett, et al. 2021. “A Practical Guide for Peach Irrigation Scheduling in Florida: HS1413, 5/2021.” EDIS 2021 (3). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1413-2021