Introduction

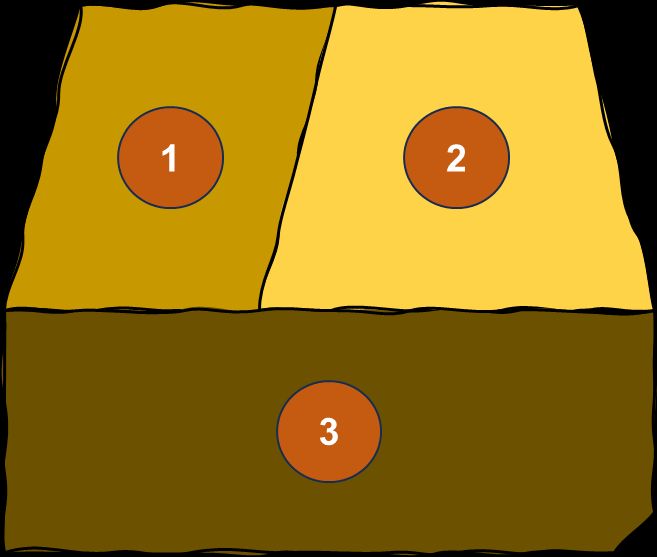

Adequate nutrient management is critical for successful commercial peach production (Figure 1). Timely and informed fertilization practices are essential to obtain high yields, optimal fruit quality, and secure long-term orchard health and productivity. Each essential nutrient must be supplied in appropriate amounts to support proper tree growth and development. Nutrient sufficiency ranges serve as valuable tools for assessing orchard health and guiding decision-making. While nutrient deficiencies often manifest through visual symptoms, particularly in leaves, these signs typically appear only after the plant is already under nutritional stress. Recognizing such symptoms can help identify which nutrients the plant may be lacking; however, a solid nutrient management program should be based on regular soil and foliar sampling to detect issues before symptoms appear. This publication provides suggested nutrient sufficiency ranges for peach trees, along with practical guidelines for identifying nutrient deficiency symptoms and conducting soil and foliar sampling in the orchard. Its goal is to support county Extension agents, Extension faculty, growers, and homeowners with general and practical guidelines for optimizing nutrient management in peach orchards.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Nutrient Sufficiency Ranges and Deficiency Symptoms

Plants require 17 essential nutrients to survive and to produce a healthy crop. The environment sufficiently supplies carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), sulfur (S), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg) are called macronutrients and generally exceed 0.1% of the plant’s total dry weight. On the other hand, boron (B), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), chlorine (Cl), molybdenum (Mo), and nickel (Ni) are called micronutrients, and plants generally require them only in a few parts per million (ppm). Plants cannot complete their life cycle without sufficient amounts of each of these nutrients.

Table 1 summarizes nutrient sufficiency ranges for macro- and micronutrients in peach leaves. Nitrogen levels in the leaves of Florida-grown, low-chill peaches ‘TropicBeauty’ and ‘UFSun’ have been found to fall within those sufficiency ranges. However, while most nutrients in ‘UFSun’ peaches grown in Florida align with these sufficiency ranges, K concentrations exceeded the suggested range, whereas Cu concentrations fell below it. It is important to remember that specific nutrient sufficiency ranges for a crop may change depending on the location, soil texture, soil pH, rainfall, and maximum and minimum temperatures, among other environmental conditions. Consequently, fertilization management practices need to be adapted to the local conditions of our state.

Table 1. Suggested nutrient deficiency thresholds and sufficiency ranges for peach leaf tissue (Layne and Bassi 2008).

Macronutrients and micronutrients play essential roles in plant growth, development, and metabolism. Moreover, nutrient deficiencies can significantly impair tree growth, health, and productivity. The following paragraphs briefly describe the critical functions of each essential nutrient and some guidelines for recognizing potential deficiencies based on visual symptoms.

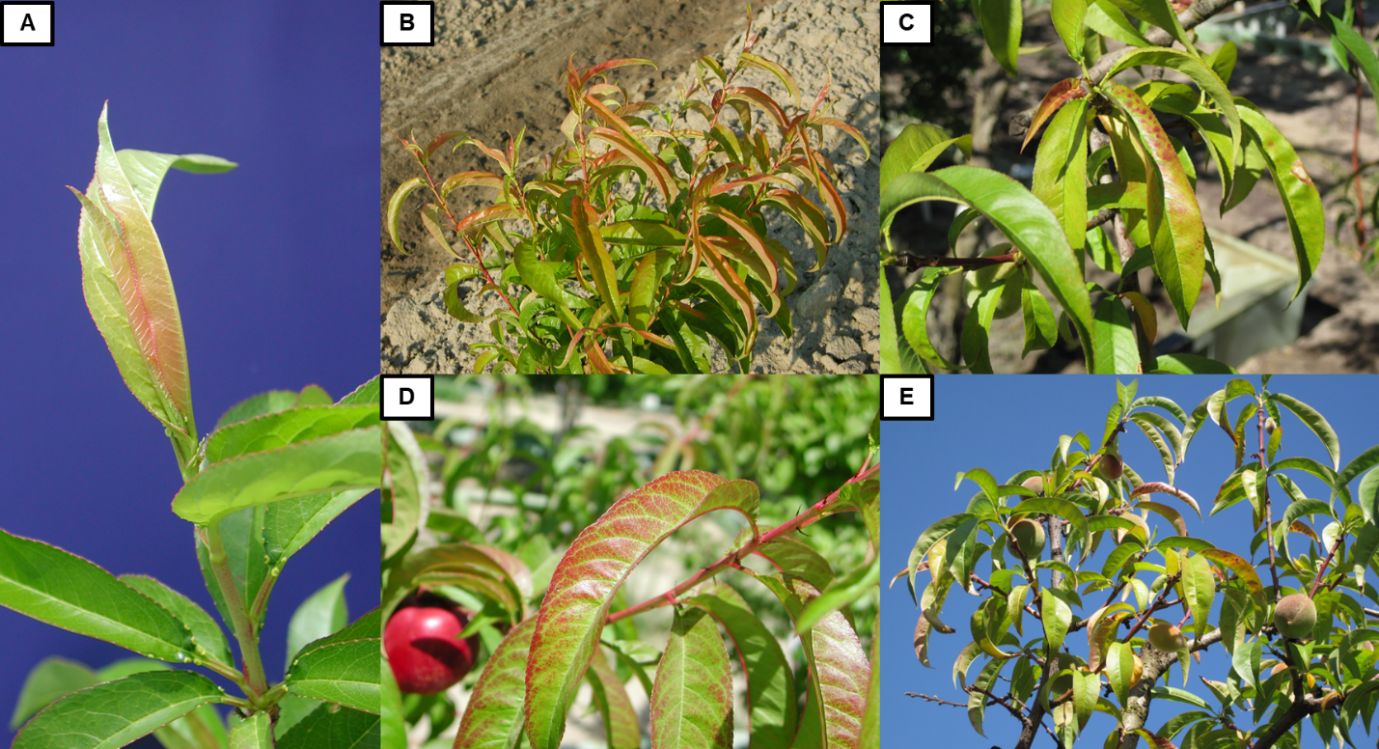

Nitrogen (N) is crucial in the structure of nucleic and amino acids, the latter being essential for the synthesis of proteins and enzymes. The sufficiency range for N in peaches is between 2.60% and 3.50% of dry weight. Most of the N used at the beginning of the growing season is obtained from reserves in scaffold branches, roots, trunks, and shoots. Later in the season, N is obtained directly from the soil. A light green or yellow chlorotic appearance initially observed on mature leaves is a typical symptom associated with N deficiency (Figure 2). Red coloration on shoots and leaf blades can also be observed, advancing into red or brown spots in the leaves. New growth is small, and older growth might drop prematurely. Although N deficiency does not affect flower density or fruit set, it does affect fruit yields by reducing fruit size as a consequence of shorter shoots. The lack of N also affects fruit quality by generating astringent and fibrous fruits.

Credit: Images facilitated by © 2023 Regents of the University of California. Used by Permission.

Phosphorus (P) is essential for the synthesis of ATP, the molecule used as an energy source in living organisms. Phosphorus is also present in nucleic acids. The sufficiency range for P is between 0.14% and 0.40% of dry weight. Similar to N, the P required to support growth at the beginning of the growing season is obtained from tree reserves. After canopy development, P is mostly used for fruit development. After harvest, trees start to accumulate P for the following year’s crop. Cases of P deficiency in peaches grown in the field are uncommon. Interestingly, peaches and other fruit crops have rarely shown any response to P fertilization, although an increase in growth has been reported in a few cases. To observe the effects of P deficiency, peach trees were grown using sand as a substrate. The initial symptom is a reduction in growth, without visual changes on leaves. Under continuous deficiency, young leaves become abnormally narrow and flat, with a leathery texture and dark purple-green appearance (Figure 3). The fruit’s skin turns fragile and rubbery, while the fruit’s flesh becomes soft, acidic, and low in eating quality.

Credit: Images facilitated by © 2023 Regents of the University of California. Used by Permission.

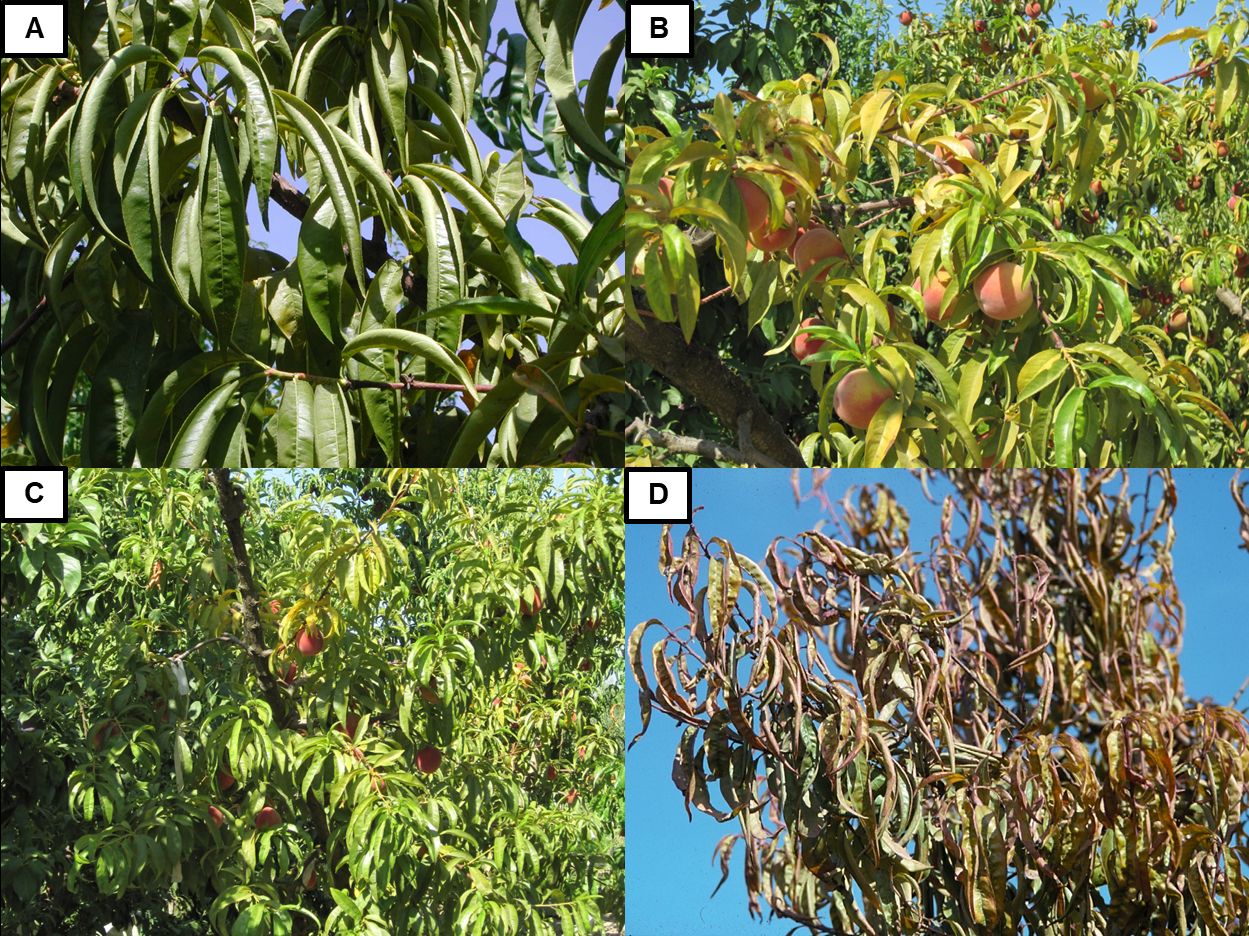

Potassium (K) is highly mobile in plants, and it is important for regulating plant turgor (tissue rigidity) and stomatal activity (gas and water exchange processes). It also acts as an activator for many enzymes. Potassium sufficiency ranges for peaches are generally between 2.00% and 3.00% of dry weight. Cases of K deficiency are common, but most of them can be solved easily with K fertilization. Typical leaf symptoms are pale-green, blueish-green, or chlorotic leaves; leaf rolling in mid-summer; and necrosis of the leaf margins (Figure 4). Shoots acquire a reddish coloration, and flower bud initiation declines significantly. In severe cases of deficiency, shoot growth ceases, and flower bud development reduces dramatically. Fruit developed under K deficiency are pale in color and small in size, thus reducing yield. Additionally, K deficiency may reduce fruit quality and postharvest life.

Credit: Images facilitated by © 2023 Regents of the University of California. Used by Permission.

Calcium (Ca) is important for the development of cell walls and membranes. It has also been associated with the successful germination of the pollen grain and in plant protection from toxins. It is important for fruit quality, especially for postharvest characteristics. Preharvest applications have been observed to reduce rot, help maintain firmness, and improve appearance and aroma. Sufficiency ranges for Ca are between 1.50% and 3.00% of dry weight. Similar to P, cases of Ca deficiency in peaches are uncommon. To observe Ca deficiency symptoms, hydroponic studies were performed on seedlings and small trees grown in sand. The first evident symptom is a reduction of root growth. In leaves, chlorosis at the margins transitions to necrosis, leading to defoliation. Additionally, the tips of some shoots may die back. Brittle bark and enlarged lenticels on the trunk might be observable. Fruit produced under Ca deficiency conditions are smaller, with reduced sugar content and poor color and flavor.

Magnesium (Mg) is an important component of the chlorophyll molecule, and it also works as an enzyme activator. Sufficiency ranges for Mg are generally between 0.30% and 0.80% of dry weight. The Ca/Mg ratio in a healthy peach tree should be approximately 2.60, and the K/Mg ratio should be close to 3.70. The first Mg deficiency symptom is often a pale-green discoloration of the leaf tips and margins of older leaves, later transitioning to chlorosis and potentially necrosis (Figures 5A and 5B). These symptoms might not be visible in younger leaves. Leaf blade deformation may also occur, with dark-green or blue-green leaf coloration, followed by interveinal chlorosis or necrotic brown spots.

Credit: Images facilitated by © 2023 Regents of the University of California (A, D, E, I) and © Yara (B, C, F, G, H). Used by Permission.

Sulfur (S) is an important component of many proteins and enzymes. Sufficiency ranges for S are between 0.14% and 0.40% of dry weight. Cases of S deficiency are rarely observed in peach orchards, and only a few reports have mentioned either deficiency symptoms in the field or a positive response to S fertilization. As occurred with P and Ca, S deficiency symptoms have been analyzed by growing peaches in sand. Nitrogen and S deficiency symptoms are similar, producing reduced growth with small chlorotic leaves turning whitish, although symptoms of S deficiency tend to start in young leaves (Figure 5C). Additionally, necrosis along the leaf margins has been reported under severe S deficiency.

The sufficiency range for Zinc (Zn) in healthy peaches is between 20 and 50 ppm. Zinc has been reported as a component of approximately 80 plant proteins, and it is important for the synthesis of auxin. Lack of auxin can generate stunted leaves and shoots, and it is the cause of “little leaf disorder” (Figure 5D and 5E). Little leaf disorder is an important limitation for peach production in some regions in the United States, occurring particularly during cold spring conditions. It is the second most common nutrient deficiency problem in California, after N. Under Zn deficiency, interveinal chlorosis is the first observable symptom, although it is difficult to differentiate from Mn deficiency. Later, short internodes and narrow pointed leaves are observable at the terminal shoots associated with the little leaf symptom (also known as rosetting). Finally, older leaves drop prematurely, along with shoot dieback. Bud development reduces significantly, and fruits tend to be smaller and flattened with thick skin and a short shelf-life.

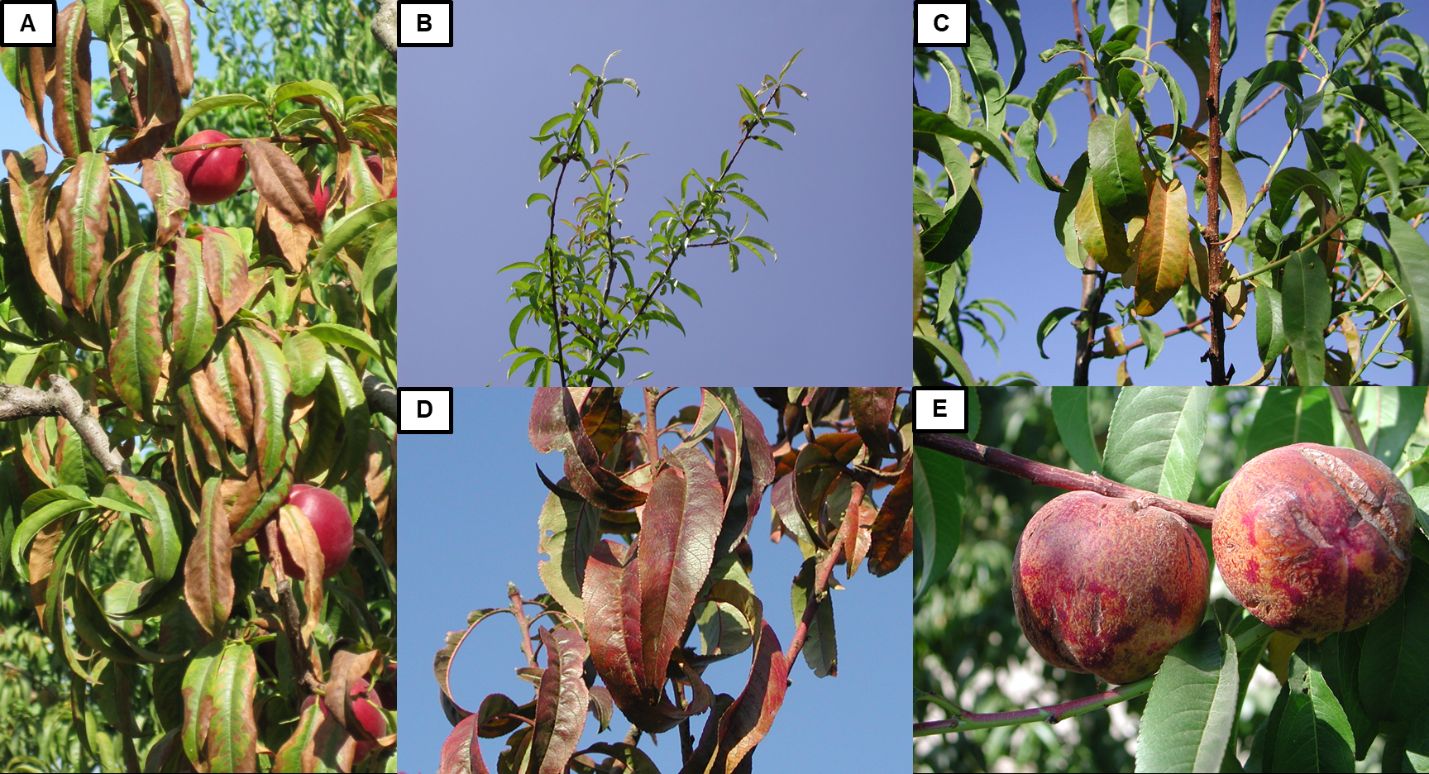

The specific function of Boron (B) is not clear, although it is considered to play an important role in pollen tube growth, cell wall synthesis, membrane integrity, water uptake, the production of some hormones, and the metabolism of carbohydrates. Generally, sufficiency ranges for B are between 30 and 70 ppm. Boron deficiency is commonly observed in many crop species around the world. Fortunately, peaches are resilient to B deficiency due to the mobility of the nutrient in this and other species of the Rosaceae family. Moreover, B deficiency cases have been seldom reported under field conditions. Flower buds failing to break in spring might be the first indication of B deficiency. These buds will eventually develop a brown coloration and die. Some weeks later, shoot dieback will also be observable. Vegetative buds might survive and grow normally, but the first expanding leaves will be deformed. In other cases, no shoot dieback was reported, but vegetative buds produced short, deformed shoots with asymmetrical leaves having chlorotic margins. Boron deficiency also reduces fruit set. The fruit that do complete development typically show no external symptoms, although necrotic areas in the flesh around the pit may be present. Generally, B deficiency symptoms are not observed in leaves but, rather, in fruit (Figure 5F).

Iron (Fe) is an important component of many enzymes and proteins, and it is necessary for the formation of chlorophyll. It is critical for the transfer of energy during photosynthesis and respiration. Sufficiency ranges for Fe are between 80 and 250 ppm of dry weight. Peaches are particularly susceptible to lime-induced chlorosis, also called Fe chlorosis. This is a common issue around the world, where Fe is immobilized in alkaline, calcareous soils (pH > 7.5). Iron deficiency might be difficult to detect with foliar analysis, so the observation of potential visual symptoms is important. Typical symptoms include completely chlorotic, unevenly distributed leaves with green veins, which appear first in young leaves and later in older leaves (Figure 5G). Affected leaves can eventually appear bleached from the loss of chlorophyll. Additionally, burned leaf spots and widespread shoot dieback can be observed. Under severe deficiency, overall vegetative and reproductive development reduces, including fruit production and size.

Manganese (Mn) is an important activator for several enzymes and plays a critical role in photosynthesis. Sufficiency ranges for Mn are between 40 and 200 ppm. Generally, Mn deficiency does not affect vegetative growth and yield, so it is not considered a serious issue. However, severe cases have been reported. The first symptoms of severe Mn deficiency are small and irregular, interveinal, light green spots in old leaves. The spots expand, but the area surrounding the veins usually stays green (Figure 5H). Dieback of shoots and early defoliation can also be observed, along with an important reduction of flowering and fruit set, consequently reducing yields.

Copper (Cu) in plants is mainly associated with the transference of energy during the photosynthetic process, although it also serves other functions. Sufficiency ranges for Cu are between 5 and 16 ppm of dry weight. Although deficiency issues associated with this nutrient are uncommon in peach orchards, the first visible Cu deficiency symptoms are pale green to bright yellow leaves with no changes in the vein coloration during spring. Later, shoot tip dieback and abnormal bud development produce a bushy appearance (Figure 5I). Fruit production can decrease severely.

Although visual symptoms can be a useful initial tool to diagnose nutrient deficiencies, it is strongly suggested to confirm these observations with plant tissue analysis. This is particularly important when observing potential micronutrient deficiencies in the orchard, as excessive micronutrient applications can easily lead to toxicity.

Determining Nutrient Needs in the Orchard

It is important to collect soil and plant tissue samples representative of the orchard in order to make adequate fertilization management decisions. Unless there are known areas with different soil attributes or plant performance, samples should be collected evenly across the orchard. Samples coming from plots with different peach cultivars or soil types should be kept separate and amended based on the corresponding testing results.

Soil Sampling Procedure

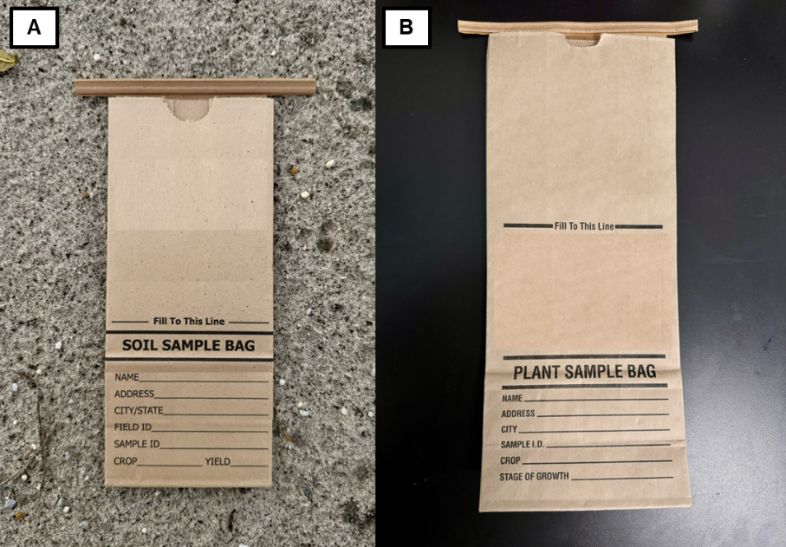

Analysis of soil fertility is critical for developing an appropriate nutrient management program. It is particularly important to sample 6–10 weeks ahead of planting to allow for adequate planning and initial nutrient applications. Consider the soil test report carefully to help determine the nutrient application rates, times, and amendments, if any, required in the following seasons. The necessary supplies are a soil auger (cylindrical or spiral tool that digs for the soil sample), containers to mix homogenously and obtain composite soil samples, and paper sample bags (Figure 6).

Credit: Jonathan Clavijo-Herrera, UF/IFAS

The following steps are suggested for the proper collection of soil samples:

- For new orchards, perform soil sampling 6–10 weeks before planting. For established orchards, collect soil samples right after harvest. It is important to divide the orchard into uniform plots, considering scion and rootstock cultivars, soil type, irrigation regime, and other characteristics important for the orchard, to ensure the collection of representative samples (Figure 7). Contact your local Extension agent or visit the USDA-NRCS Web Soil Survey website to determine the soil type in your location. If trees with deficiency symptoms are observed, collect samples from the soil around those trees and submit them to the laboratory separately.

Credit: Jonathan Clavijo-Herrera, UF/IFAS

2. Label the sample bags properly (Figure 6A). It is important to label sample bags clearly and include information such as location, date, crop/cultivar, and sample number.

3. A soil auger, a bucket, and paper bags are needed for soil sample collection (Figure 8A). Ideally, collect three composite samples per acre. Each composite sample will need five or more subsamples, from at least five different trees. Place the auger 1 to 5 feet from the trunk (depending on the size of the tree) to collect a sample (Figure 8B). Collecting samples at a depth of 12 inches is suggested (Figure 8C).

Credit: Jonathan Clavijo-Herrera, UF/IFAS

4. To prepare each composite sample, put the subsamples in the bucket (Figure 9A) and mix thoroughly (Figure 9B). Then, place one fistful (roughly 1 pound) of this soil mixture in a paper bag (Figure 9C).

Credit: Jonathan Clavijo-Herrera, UF/IFAS

5. Ship the samples to your preferred diagnostic laboratory. The UF/IFAS Extension Soil Testing Laboratory (ESTL) at UF’s main campus in Gainesville provides soil sample analytic services.

Plant Tissue Sampling Procedure

Plant tissue sampling is critical to determine if your fertilization program has been adequately supporting a healthy and productive orchard. Plant tissue samples are the best indicator of the overall nutrient uptake capacity and performance of the trees under the specific growing and management conditions. Taking samples makes it possible to apply corrective measures if required. For peaches and other fruit tree species, the standard method for plant tissue sampling is to collect mature leaves after harvest (typically June in Florida). This method has certain disadvantages, mainly due to the timing of the analysis, which is late in the season and may not allow the application of corrective measures to help the current season’s crop. However, this remains the most widely accepted method since it helps to prepare the trees for the following season. To collect representative samples, consider the following steps:

- Divide the orchard into plots according to soil type, plant age, rootstock cultivar, scion cultivar, irrigation regime, and other characteristics specific to the orchard (Figure 10). If trees have visible deficiency symptoms, collect samples from those trees separately.

Credit: Jonathan Clavijo-Herrera, UF/IFAS

2. Label the paper bags for sample collection with the location, date, crop/cultivar, and sample number (Figure 6B). Using paper bags instead of plastic bags is encouraged to avoid moisture accumulation and decay of the collected leaves.

3. Gather the newest fully expanded and mature leaves of current season growth from the middle section of the canopy for foliar analysis (Figure 11). Ideally, obtain three composite samples per acre. Each composite sample should consist of 40 to 50 total leaves obtained from at least five trees, or 8 to 10 leaves per tree. Select the trees for the composite sample following a zig-zag pattern through the orchard (Figure 12). Place the leaves in the labeled sample bags.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jonathan Clavijo-Herrera, UF/IFAS

4. Store the sample bags and keep them cool and dry until shipment.

5. Ship the samples to your preferred diagnostic laboratory as soon as possible. If immediate shipment is not possible, drying the samples for storage is suggested. The UF/IFAS ESTL provides plant tissue testing services and instructions.

Conclusion

Nutrient sufficiency ranges are an essential tool for assessing orchard health. Visual symptoms, particularly in the leaves, can also indicate nutrient deficiencies. However, a strong nutrient management program requires making decisions based on solid information. Consequently, regular soil and foliar sampling should be performed in the orchard. Soil analysis is particularly useful before planting, as it guides initial fertilization practices and can help to implement amendments, if required. On the other hand, foliar sampling should be performed at least once a year to assess orchard health and determine whether the current nutrient management practices are adequate or require adjustment. These guidelines provide a general framework to optimize nutrient management and support the long-term sustainability of peach orchards in the state.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the FDACS Specialty Crops Block Grant (SCBGP) and Fertilizer Rate and Nutrient Management Programs.

Reference

Layne, D. R., and D. Bassi, eds. 2008. The Peach: Botany, Production and Uses. CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845933869.0000

Further Reading

Abarca, P., S. Felmer, M. Allende, et al. 2017. Manual de manejo delcultivo de duraznero. Boletín INIA 373. Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario, Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias. https://bibliotecadigital.ciren.cl/server/api/core/bitstreams/27c0ab76-850c-4fd3-b536-3c6444f4ecce/content

California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA). n.d. “Peach and Nectarine.” California Crop Fertilization Guidelines. https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/is/ffldrs/frep/FertilizationGuidelines/Peach_Nectarine.html

Chandler, W. H. 1937. “Zinc as a Nutrient for Plants.” Botanical Gazette 98 (4): 625–646. https://doi.org/10.1086/334670

Chandler, W. H., D. R. Hoagland, and P. L. Hibbard. 1931. “Little Leaf or Rosette of Fruit Trees.” Proceedings of the American Society for Horticultural Science 28: 556–560.

Huett, D. O., A. P. George, J. M. Slack, and S. C. Morris. 1997. “Diagnostic Leaf Nutrient Standards for Low-Chill Peaches in Subtropical Australia.” Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 37 (1): 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1071/EA96040

Johnson, R. S., H. Andris, K. Day, and R. Beede. 2005. “Using Dormant Shoots to Determine the Nutritional Status of Peach Trees.” ISHS Acta Horticulturae 721: V International Symposium on Mineral Nutrition of Fruit Plants 721, 285–290. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.721.39

Leece, D. R. 1976. “Diagnosis of Nutritional Disorders of Fruit Trees by Leaf and Soil Analyses and Biochemical Indices.” Journal of the Australian Institute of Agricultural Science 42, 3–19.

Mahler, R. L. 2004. “Nutrients Plants Require for Growth.” University of Idaho, College of Agricultural and Life Sciences. CIS 1124.

Olmstead, M., and K. Morgan. 2013. “Orchard Establishment Budget for Peaches and Nectarines in Florida: HS1223, 7/2013.” EDIS 2013 (7). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1223-2013

Sanz, M., and L. Montañés. 1995. “Flower Analysis as a New Approach to Diagnosing the Nutritional Status of the Peach Tree.” Journal of Plant Nutrition 18 (8): 1667–1675. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904169509365012

Sarkhosh, A., M. Olmstead, J. Chaparro, P. Andersen, and J. Williamson. 2018. “Florida Peach and Nectarine Varieties: Cir1159/MG374, rev. 10/2018.” EDIS 2018. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-mg374-2018

Singerman, A., M. Burani-Arouca, and M. Olmstead. 2017. “Establishment and Production Costs for Peach Orchards in Florida: Enterprise Budget and Profitability Analysis: FE1016, 7/2017.” EDIS 2017 (4). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fe1016-2017

Singerman, A., and M. P. Useche. 2020. “Impact of Citrus Greening on Citrus Operations in Florida: FE983/FE983, 2/2016.” EDIS 2016 (2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-fe983-2016

Soria Baráibar, J. 2014. Manual del duraznero: La planta y la cosecha. Boletín de divulgación INIA: 108. Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agropecuaria.

UF/IFAS. 2024. “Stone Fruit Nutrition.” Department of Horticultural Sciences. https://hos.ifas.ufl.edu/stonefruit/production/nutrition/

U. S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS). 2024. Quick Stats Tool. Last modified February 28, 2024. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/

Waters Agricultural Laboratories, Inc. 2021. “How to Take a Soil Sample.” https://watersag.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/How-To-Take-a-Soil-Sample.pdf