This EDIS publication provides an overview of the growth stages of edamame (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), a promising new crop introduced in Miami-Dade County. Notably, edamame is not registered as an invasive species in Florida (UF/IFAS 2018). This factsheet covers the physiological changes that occur during each developmental stage and offers guidance on the timing of these processes. This information also helps local small-scale growers understand the crop’s production cycle under south Florida’s climate. The audience for this EDIS publication includes vegetable growers, Extension agents, certified crop advisers (CCAs), crop consultants, and students interested in vegetable production.

Introduction

Edamame (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) is a warm-season, short-day leguminous crop that originates from China and is widely produced and consumed in many East Asian countries (Wang 2018a, 2018b). It is often integrated as a traditional ingredient in their cuisines, such as in soups, stir-fry, and roasted salad (Li et al. 2022a). In the United States, edamame is a specialty soybean grown on a small scale and consumed as a vegetable, whereas traditional soybeans are primarily cultivated for oil production and livestock feed (Nair et al. 2023). Edamame has been cultivated in several states (e.g., Arkansas, Washington State, and Virginia) and is mainly valued for its high protein content, large-seeded pods, and good taste (Ross 2012).

The edamame production cycle varies across cultivars, climates, and geographical locations. Environmental factors such as day length, temperature, and precipitation can influence the cycle timing from planting through harvest (Moseley et al. 2021). For instance, planting time in Virginia typically begins in early May through June. On the other hand, a tropical region like south Florida allows multiple growing seasons per year. At the UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center, researchers found that the crop can be cultivated in both spring (from mid-February to early May) and fall (from early October to late December). Usually, production in cold regions of the United States occurs after the last frost, once the soil temperature exceeds 15°C. The entire growing season in these regions usually lasts between 10 to 17 weeks (Miles et al. 2018; Guo et al. 2020).

As edamame is a relatively new crop in south Florida, local growers need comprehensive information about its growth cycle and phenological stages to ensure successful production, optimize harvest timing, and align with market demands. For example, knowing the emergence time of edamame allows growers to monitor seedling development and quickly identify if germination fails, enabling timely replanting. Additionally, understanding the harvest timing helps growers ensure that edamame is picked at peak freshness, maximizing pod quality and market value.

Key Growth Stages of Edamame Grown in Miami-Dade County

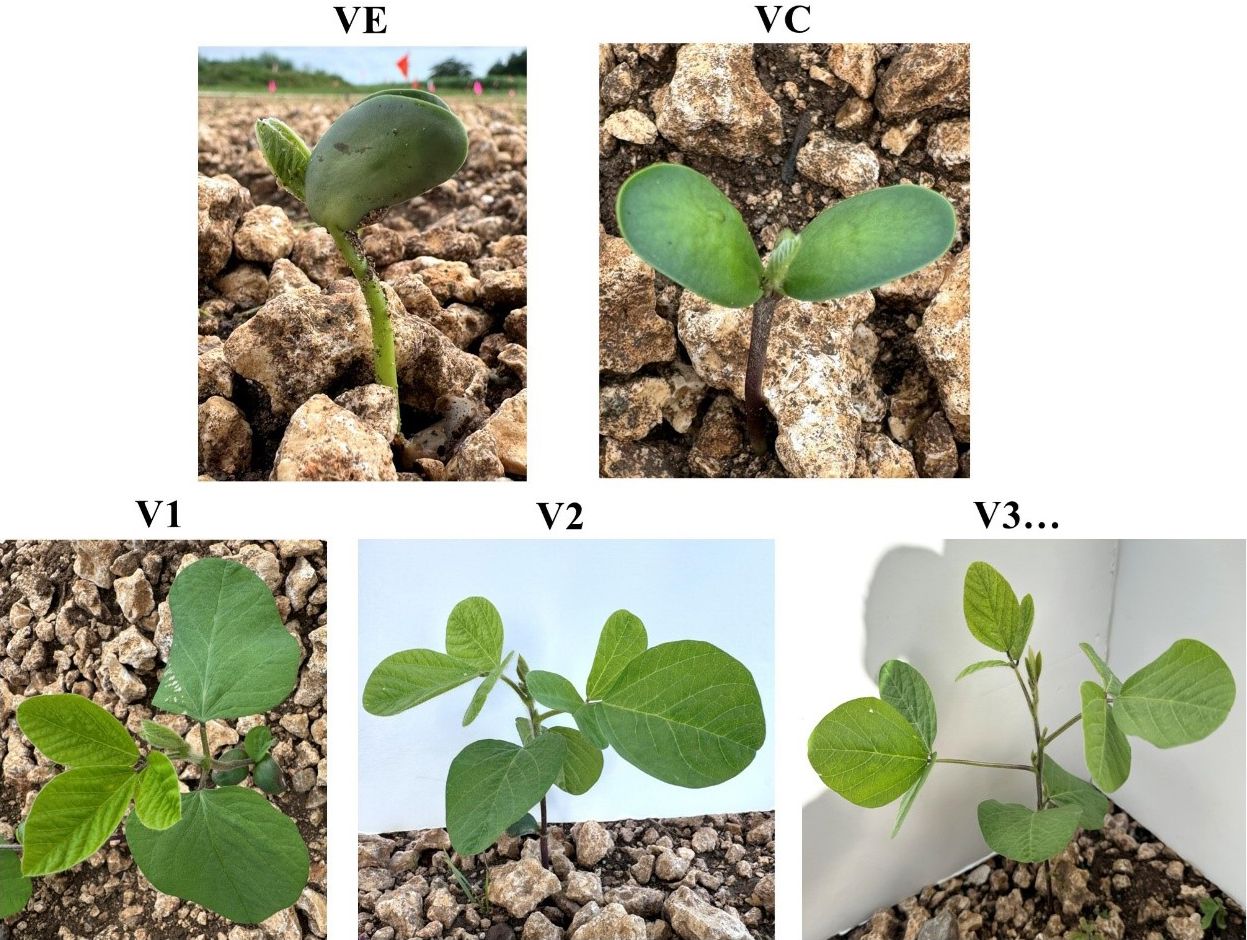

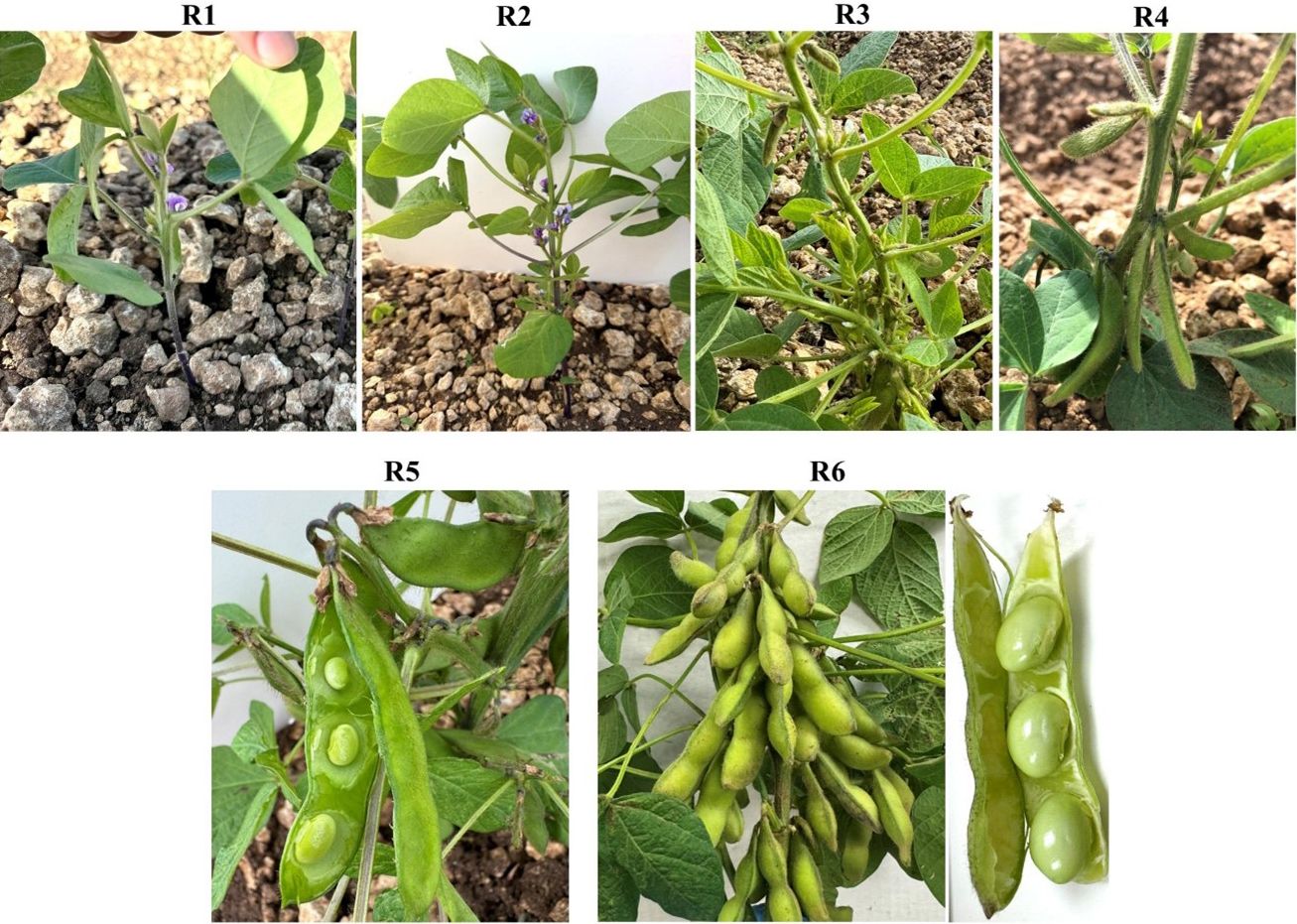

As detailed in Table 1, edamame progresses through distinct vegetative (VE–Vn) and reproductive (R1–R6) stages, each characterized by specific growth and development traits. The vegetative stages focus on leaf and node development, with the number of trifoliate leaves expanding as the plant matures. The reproductive stages begin with flowering (R1), continue through pod development and bean filling, and culminate when the beans inside the pods reach at least 80% of their full size while still retaining their green color (R6), making them suitable for pod harvest.

Table 1 illustrates the average range of days it takes for edamame plants to transition between growth stages. The data come from 16 varieties ranging from maturity group (MG) 00 to MG V. Varieties like ‘Tohya’ (MG 00) are typically grown in regions of North Dakota and Illinois (Bowen et al. 2022), while others, including ‘Chiba green’ (MG III), ‘Midori giant’ (MG III), and ‘UA-Kirksey’ (MG V), are mainly cultivated in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States (Lord et al. 2021; Ogles et al. 2016). All varieties were grown in Miami-Dade County during the fall season of 2024. Since the number of days required for each growth stage did not vary much across maturity groups, Table 1 combines and presents it as a range for all varieties. Monitoring growth stages is essential for optimizing sustainable management practices because plants require different amounts of water and nutrients at various stages, when there are changes in physiological needs, root development, and nutrient uptake efficiency. Proper irrigation and fertilization management at each phase enhance growth, maximize yield potential, and improve resource efficiency, which are especially important in the unique tropical climatic conditions of south Florida (Lacerda et al. 2025).

Table 1. Phenological development of edamame plants.

To clarify, Figure 1 illustrates the progression of leaf formation, highlighting key morphological changes at each vegetative stage as the plant progresses through its growth cycle.

Credit: Vander Lacerda, UF/IFAS

While many growers are familiar with soybean (which typically refer to grain-type soybean), they are interested in understanding the differences between them and edamame (referring to young soybean). Note that edamame and soybean are the same plant species, both sharing the same growth stages. However, key differences exist in their development and management. While both follow similar vegetative stages (VE–Vn), edamame has larger seeds, requiring more time for emergence. In the reproductive stages (R1–R6), edamame produces bigger pods, and reaches maturity when pods are still green (R6), whereas grain soybean continues to mature until the seeds dry out (beyond R6, at R7–R8). Compared to soybean yield, which is measured by dry seed, edamame yield is determined by fresh pod weight (Saha et al. 2024).

Germination and Seedling Emergence (V1–V3)

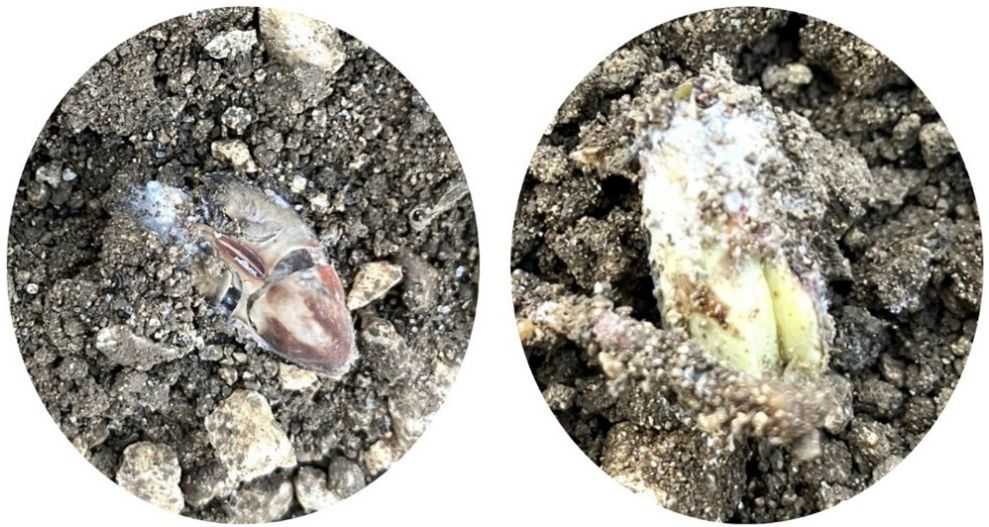

Edamame germination requires favorable soil and weather conditions for physiological changes to occur. To begin germination and ensure its success, the soil should be moist enough for seeds to absorb approximately half of their weight in water (Li et al. 2022), making adequate irrigation essential during the early development stages of edamame after planting. Edamame seeds are larger and have higher oil content compared to small-seeded vegetables (Yu et al. 2021). Consequently, they have a greater demand for oxygen during germination and are more vulnerable to germination failure when soil oxygen is limited, particularly under conditions such as waterlogging or when using aged or poor vigor seeds (Liu et al. 2012). Maintaining aerobic soil conditions (e.g., through proper seedbed preparation and effective irrigation practices) is therefore critical for successful germination. Soil temperature also plays a key role in the germination process, where favorable soil temperatures for edamame germination range from 25°C–33°C (Li et al. 2024). Exposure to high temperatures and dry soil could impede physiological processes during germination (Xu et al. 2016). Given that Miami-Dade County frequently experiences hot days, growers should carefully monitor soil temperature before selecting a planting date. Excessive moisture and cool soil conditions can slow seedling growth and increase the risk of fungal infestation (Figure 2).

Credit: Vander Lacerda, UF/IFAS

To ensure a good emergence rate, growers should slightly cover seeds with soil or compost. Normal planting depth ranges from 0.5–1 inch, but sometimes sowing depth can vary up to 2 inches depending on the gravel content in the soil. However, note that if seeds are sown deeper than 2 inches, the germination rate may decline, leading to delayed and low emergence, which results in non-uniform plant establishment. Most edamame plants will emerge anytime from five to seven days after planting. The first fertilizer application of NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) is usually broadcast prior to planting to ensure essential nutrients are available once seedlings establish and begin vegetative growth. In the initial few days after emergence, the cotyledons (i.e., the seed’s initial leaves) expand and unfold, serving as temporary storage and photosynthetic organs that provide nutrients to the developing seedling until the true leaves emerge and take over growth functions. As the seedling continues to grow and transitions to the V1 stage, it no longer relies on cotyledons as a source of energy since the development of trifoliate leaves along with other leaflets enhances the photosynthetic capacity. Some plants will start developing their first trifoliate around the first two weeks after planting.

Nitrogen fixation in the edamame plant begins around stage V2 and continues throughout the phenological cycle of the plant (NDSU 2022). Most root nodules will be found in the first 8–10 inches of the soil surface. It is highly recommended to inoculate edamame seeds with the bacteria Bradyrhizobium japonicum in the field where legumes have not been previously cultivated. This bacterium forms symbiotic relationships with legume roots, leading to the formation of nodules where atmospheric nitrogen is converted into a form usable by plants. Since roots are the primary organs for water and nutrient absorption, it is crucial that macronutrients such as phosphorus and potassium are available to support the early root growth during that stage. Growers should not place fertilizers for these nutrients within 2–3 inches of the seeds to avoid direct contact with the seedlings and prevent salt injury.

The use of herbicides is crucial for effective weed management in edamame cultivation, as weeds can compete with plants for essential resources such as light, water, and nutrients. Growers should apply preemergence herbicides (i.e., S-metolachlor) before or immediately after planting to help control weeds during the early stages of growth when the plants are most vulnerable. These applications reduce early competition, ensuring optimal conditions for germination and seedling development. For postemergence herbicide applications, it is vital to wait until the edamame plants have developed sufficient foliage, typically after the first trifoliate leaves have expanded. This minimizes the risk of herbicide injury and ensures the plants are robust enough to tolerate the application.

Vegetative Growth and Canopy Development (V4–V6)

After the development of the third set of nodes, more trifoliate leaves (Vn) will grow, depending on the variety and abiotic conditions, until the plant can transition to the reproductive phase. Usually, plants grow quickly from emergence through all vegetative stages, taking one to four weeks in south Florida’s subtropical climate. As the plants develop more leaves, they become more susceptible to infestation by pests such as caterpillars, green beetles, and thrips (Dittmar et al. 2023). For example, caterpillars can affect early stages (like VC) by causing damage or the loss of both cotyledons, and they can reduce yield. As previously stated, effective weed management is essential during the vegetative stages since weeds can compete with the plants for water, nutrients, and light. Cultural practices or herbicide application before emergence can achieve control of grass and broadleaf weeds (Frey et al. 2023). Generally, the pests and weeds observed in edamame production in Miami-Dade County are similar to those reported in green beans. Due to a lack of edamame-specific pest and weed management guidelines for cultivation in the region, it is suggested that growers adopt integrated control strategies established for green beans (Dittmar et al. 2023; Qureshi et al. 2020). However, it is always necessary to check pesticide and herbicide labels to ensure the products are approved for use on edamame, which may also be listed as vegetable soybean or immature soybean on product labels. By the V4 stage, plants typically have developed at least four nodes with fully expanded trifoliate leaves, and their canopy begins to close, which helps suppress weed growth naturally by limiting sunlight penetration to the soil. This period is crucial for root development and nutrient uptake, as the plant’s demand for macronutrients, particularly nitrogen, reaches a critical point (Pardeshi et al. 2024). Proper nodulation should be evident by this stage, with active nitrogen fixation contributing significantly to the plant’s nitrogen supply.

By the subsequent Vn stages, plants generally reach their maximum vegetative height and leaf area, creating a dense canopy that optimizes light interception. These stages are also critical for ensuring sufficient water availability. Water stress during Vn can lead to reduced leaf expansion and lower photosynthetic rates, ultimately impacting yield potential. Growers should monitor plants closely for any signs of nutrient deficiencies or pest damage, as these can compromise the plant’s ability to transition effectively into the reproductive phase.

Reproductive Development (R1–R6)

Edamame grown in the fall season in Miami-Dade County typically begins flowering (R1) around five weeks after planting. At this phase, most of the plants will develop four to six nodes (Figure 3). Growth indices such as canopy height should not vary much from bloom to pod set. However, ‘Kahala’ (a variety developed by the University of Hawaii; Takeda and Sakuoka 1997) tends to develop more leaves after the flowering stage, usually with a large percentage of small pods. Nitrogen fertilizer is crucial during the pod set stage because the plants need more nitrogen for pod formation and seed filling. However, too much nitrogen could reduce the yield by decreasing the number of pods. Nitrogen fixation capacity increases rapidly during the reproductive stages and decreases as the chlorophyll content degrades (Wang et al. 2022; Ciampitti et al. 2021).

Credit: Vander Lacerda, UF/IFAS

Growers should complete all fertilizer applications prior to the seed-filling stage. When using slow-release fertilizer, plants will have sufficient time to absorb the necessary nutrients for seed development. Currently, there is no UF/IFAS fertilizer recommendation for edamame production in Miami-Dade County, so it is suggested that growers refer to the fertilizer recommendation established for snap beans as a guide for nitrogen application. Nitrogen fertilizer is particularly important for maximizing yields in legumes, with rates similar to those recommended for snap beans, ranging from 70–100 lb/acre (Hochmuth and Hanlon 2010; Ozores-Hampton et al. 2015). Proper nutrient management at this stage helps to enhance both quality and final yield. As plants enter their reproductive stages, they become more susceptible to leaf and pod diseases. To manage these diseases effectively, it is recommended to start pesticide applications early in the reproductive stages. Additionally, during the late reproductive stages, plants typically have completed their growth cycle and require less water. Therefore, reducing irrigation to once per week is advisable, depending on weather and soil conditions (Jaybhay et al. 2019).

At the maturation stage (R6), root growth is complete, and root nodule number and pod weight are maximized (Torrion et al. 2012). During the fall season, most edamame pods are ready to be harvested within 10–11 weeks after planting. For instance, ‘Chiba green’ pods generally reach maturity in approximately 10 weeks post-planting, while ‘Kahala’ will take one more week for the beans to fill completely. Growers should monitor plants daily as pods approach maturity to ensure a timely harvest. Edamame pods transition rapidly from immature to overripe, turning yellow and losing marketability. The ideal harvest window is typically within one week, depending on environmental conditions and cultivar characteristics.

Conclusion

The successful cultivation of edamame in south Florida requires a comprehensive understanding of its growth stages and the region’s unique environmental conditions. The crop progresses through distinct phases, beginning with germination and seedling emergence (VE–VC), where cotyledons emerge and the first trifoliate leaves expand (V1). At the early stages, maintaining well-aerated soil and ensuring adequate irrigation are essential to support good germination, healthy root system development, and overall seedling establishment. This is followed by vegetative growth and canopy development (V4–Vn), as characterized by the continued formation of trifoliate leaves, canopy expansion, and establishment of a foundation for photosynthesis and biomass accumulation. The vegetative stages are some of the most important phases of edamame production, as the plant prepares to support reproductive structures. Therefore, proper nutrient, weed, and pest management practices help to ensure optimal biomass production and canopy health. Finally, reproductive development (R1–R6) marks the transition from flowering to pod formation, with pods ready for harvest when they reach at least 80% of their full size, while their seeds remain green and tender (R6). During these stages, effective pest monitoring is key to preventing infestations of insects that target apical buds and developing pods since damage can significantly reduce yield and pod marketability. This knowledge serves as a valuable foundation for making informed decisions that enhance crop performance and overall production efficiency.

References

Bowen, R., A. Bardeau, S. Schultz, and G. L. Hartman. 2022. “Registration of Seven Disease‐ and Pest‐Resistant Vegetable Soybean Germplasm Lines.” Journal of Plant Registrations 16 (2): 438–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/plr2.20215

Ciampitti, I. A., A. F. de Borja Reis, S. C. Córdova, et al. 2021. “Revisiting Biological Nitrogen Fixation Dynamics in Soybeans.” Frontiers in Plant Science 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.727021

Dittmar, P. J., N. S. Dufault, J. Desaeger, J. Qureshi, N. S. Boyd, and M. L. Paret. 2023. “Chapter 4. Integrated Pest Management: VPH ch. 4, CV298, rev. 6/2023.” EDIS 2023 (VPH). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cv298-2023

Frey, C., P. J. Dittmar, D. R. Seal, et al. 2023. “Chapter 11. Legume Production: VPH ch. 11, rev. 6/2023.” EDIS 2023 (VPH). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cv125-2023

Guo, J., A. Rahman, M. J. Mulvaney, et al. 2020. “Evaluation of Edamame Genotypes Suitable for Growing in Florida.” Agronomy Journal 112 (2): 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20136.

Hochmuth, G., and E. Hanlon. 2010. “A Summary of N, P, and K Research with Snap Bean in Florida: SL331/CV234, rev. 8/2010.” EDIS 2010 (7). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cv234-2010.

Jaybhay, S. A., P. Varghese, S. P. Jaybhay, B. D. Idhol, B. N. Waghmare, and D. H. Salunkhe. 2019. “Response of Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] to Irrigation at Different Growth Stages.” Agricultural Science Digest 39 (2): 132–135. https://doi.org/10.18805/ag.D-4932

Lacerda, V. R., B. N. S. Costa, and X. Li. 2025. “Sustainable Practices in Tropical Horticulture: A Path to Resilient Agricultural Systems.” Technology in Horticulture 5: e004. https://doi.org/10.48130/tihort-0024-0033

Li, X., K. Liu, S. Rideout, L. Rosso, B. Zhang, and G. E. Welbaum. 2024. “Seed Physiological Traits and Environmental Factors Influence Seedling Establishment of Vegetable Soybean (Glycine max L.).” Frontiers in Plant Science 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1344895

Li, X., G. E. Welbaum, S. L. Rideout, W. Singer, and B. Zhang. 2022. “Vegetable Soybean and Its Seedling Emergence in the United States.” In Legumes Research, edited by J. C. Jimenez-Lopez and A. Clemente. Vol. 1. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.102622

Liu, G., D. M. Porterfield, Y. Li, and W. Klassen. 2012. “Increased Oxygen Bioavailability Improved Vigor and Germination of Aged Vegetable Seeds.” HortScience 47 (12): 1714–1721. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.47.12.1714

Liu, G., E. H. Simonne, K. T. Morgan, et al. 2024. “Chapter 2. Fertilizer Management for Vegetable Production in Florida: VPH ch. 2, CV296, rev. 6/2024.” EDIS 2024 (VPH). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cv296-2023

Lord, N., T. Kuhar, S. Rideout, et al. 2021. “Combining Agronomic and Pest Studies to Identify Vegetable Soybean Genotypes Suitable for Commercial Edamame Production in the Mid-Atlantic U.S.” Agricultural Sciences 12 (7): 738–754. https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2021.127048

Miles, C. A., J. O’Dea, C. H. Daniels, and J. King. 2018. “Edamame.” PNW524. A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication. https://pubs.extension.wsu.edu/product/edamame/

Moseley, D., M. P. da Silva, L. Mozzoni, et al. 2021. “Effect of Planting Date and Cultivar Maturity in Edamame Quality and Harvest Window.” Frontiers in Plant Science 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.585856

Naeve, L. S. 2018. “Soybean Growth Stages.” University of Minnesota Extension. https://extension.umn.edu/growing-soybean/soybean-growth-stages#days-between-stages-539862

Nair, R. M., V. N. Boddepalli, M.-R. Yan, et al. 2023. “Global Status of Vegetable Soybean.” Plants 12 (3): 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12030609

North Dakota State University (NDSU). 2022. “Nitrogen and Soybean Nodulation.” NDSU Agriculture. https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/ag-hub/ag-topics/crop-production/crops/soybeans/nitrogen-and-soybean-nodulation

Ogles, C. Z., E. A. Guertal, and D. B. Weaver. 2016. “Edamame Cultivar Evaluation in Central Alabama.” Agronomy Journal 108 (6): 2371–2378. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2016.04.0218

Ozores-Hampton, M., Q. Zhu, and Y. Li. 2015. “Snap Bean Soil Fertility Program in Miami-Dade County: HS1261, 5/2015.” EDIS 2015 (4). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1261-2015

Pardeshi, P. P., P. A. Sonkamble, D. R. Rathod, et al. 2024. “Characterization of Vegetable Soybean (Edamame) Germplasm and Assessment of Optimal Food Quality Traits.” Indian Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding 84 (03): 482–491. https://doi.org/10.31742/ISGPB.84.3.19

Qureshi, J. A., D. Seal, and S. E. Webb. 2020. “Insect Management for Legumes (Beans, Peas): ENY-465/IG151, rev. 7/2020.” EDIS 2020 (4). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ig151-2003

Ross, J. 2012. “Edamame Production Practices: What We Know Now.” Presentation at the Arkansas Soybean Research Summit, University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture, December 4, 2012.

Saha, M., M. Chavan, T. Onkarappa, R. L. Ravikumar, and U. Das. 2024. “Pheno-Morphological Characterization and Genetic Diversity Assessment of Grain and Vegetable Soybean (Glycine max. (L.) Merrill) Lines for Breeding Advancements.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.01.626274

Takeda, Y. K., and T. R. Sakuoka. 1997. "Vegetable Soybean.” CTAHR Factsheet HGV-14. University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Extension. https://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/HGV-14.pdf

Torrion, J. A., T. D. Setiyono, K. G. Cassman, R. B. Ferguson, S. Irmak, and J. E. Specht. 2012. “Soybean Root Development Relative to Vegetative and Reproductive Phenology.” Agronomy Journal 104 (6): 1702–1709. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2012.0199

University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS). 2018. “Assessment of Non-Native Plants in Florida’s Natural Areas.” Accessed October 15, 2025. https://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu/

Wang, J., G. Chen, X. Li, et al. 2022. “Transcriptome and metabolome analysis of a late-senescent vegetable soybean during seed development provides new insights into degradation of chlorophyll.” Antioxidants 11 (12): 2480. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11122480

Wang, K.-c. 2018a. “East Asian Food Regimes: Agrarian Warriors, Edamame Beans and Spatial Topologies of Food Regimes in East Asia.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (4): 739–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1324427

Wang, K.‐c. 2018b. “Food Safety and Contract Edamame: The Geopolitics of the Vegetable Trade in East Asia.” Geographical Review 108 (2): 274–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12254

Xu, Y., A. Cartier, D. Kibet, et al. 2016. “Physical and Nutritional Properties of Edamame Seeds as Influenced by Stage of Development.” Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 10: 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-015-9293-9

Yu, D., T. Lin, K. Sutton, et al. 2021. “Chemical Compositions of Edamame Genotypes Grown in Different Locations in the US.” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.620426