Introduction

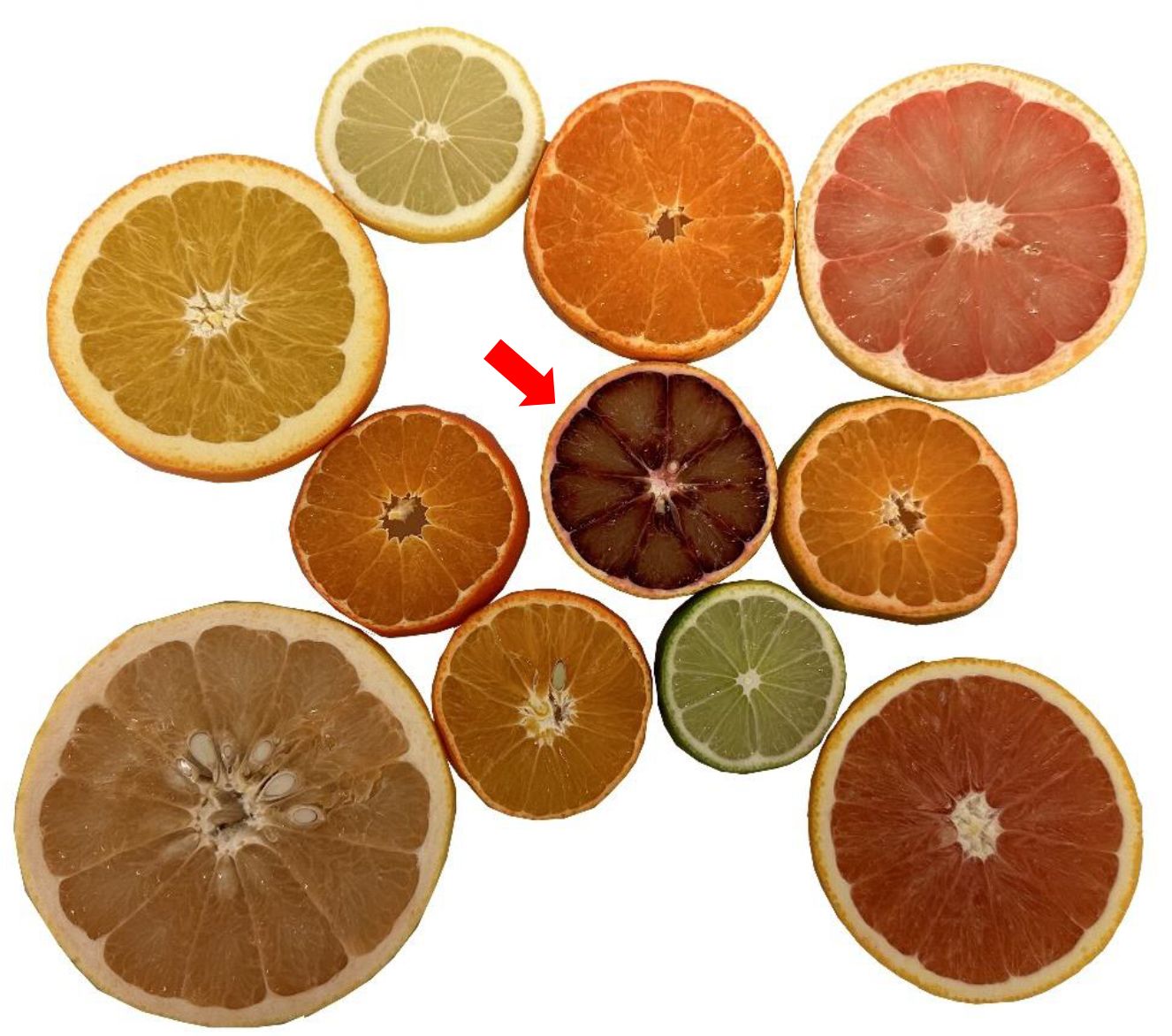

Blood orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) is one of four groups within the sweet orange classification. It is characterized by red flesh (Figure 1), resulting from the accumulation of anthocyanin pigment. Among the commercial citrus fruit types, blood oranges are the only ones capable of synthesizing anthocyanin pigments in the flesh, and sometimes in the peel (Figure 2). Blood oranges ascended from a spontaneous bud mutation and include various cultivars and accessions that show different levels of anthocyanin pigment in the flesh under the same climate conditions and cultural practices. They are popular among consumers for their taste, appearance, and nutritional benefits, as they are a rich source of anthocyanin, ascorbic acid, and hydroxycinnamic acids — all antioxidants that can be beneficial for human health. Blood oranges also contain other vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, such as vitamins A, E, and K, potassium, magnesium, calcium, iron, copper, manganese, β-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin. Anthocyanin content is an important quality index for blood orange fruit.

This work was supported by the Research Capacity Fund (Hatch) projects, project award no. 7004457, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

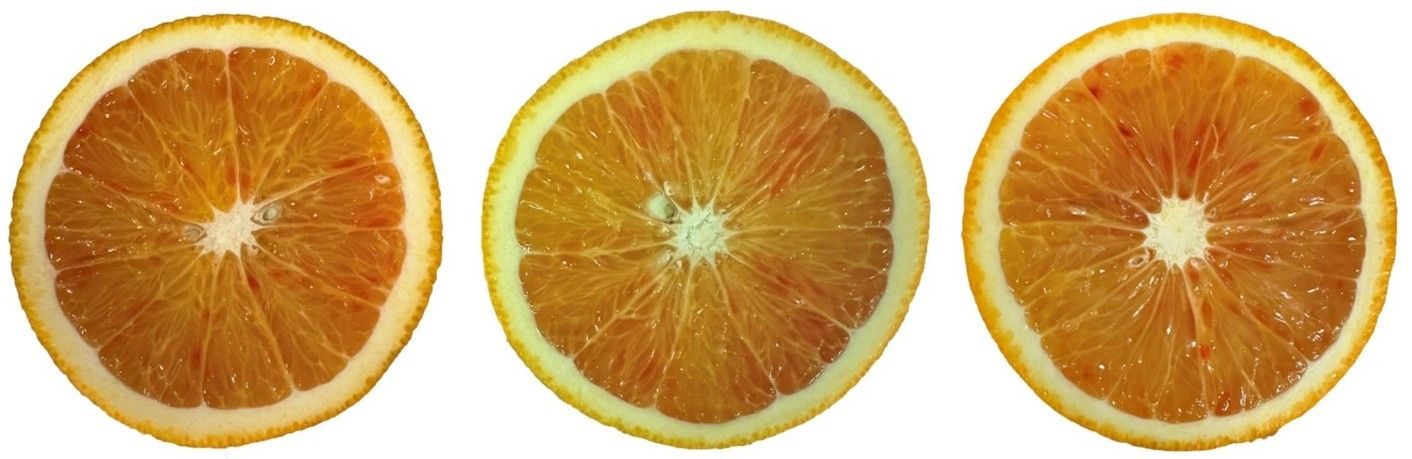

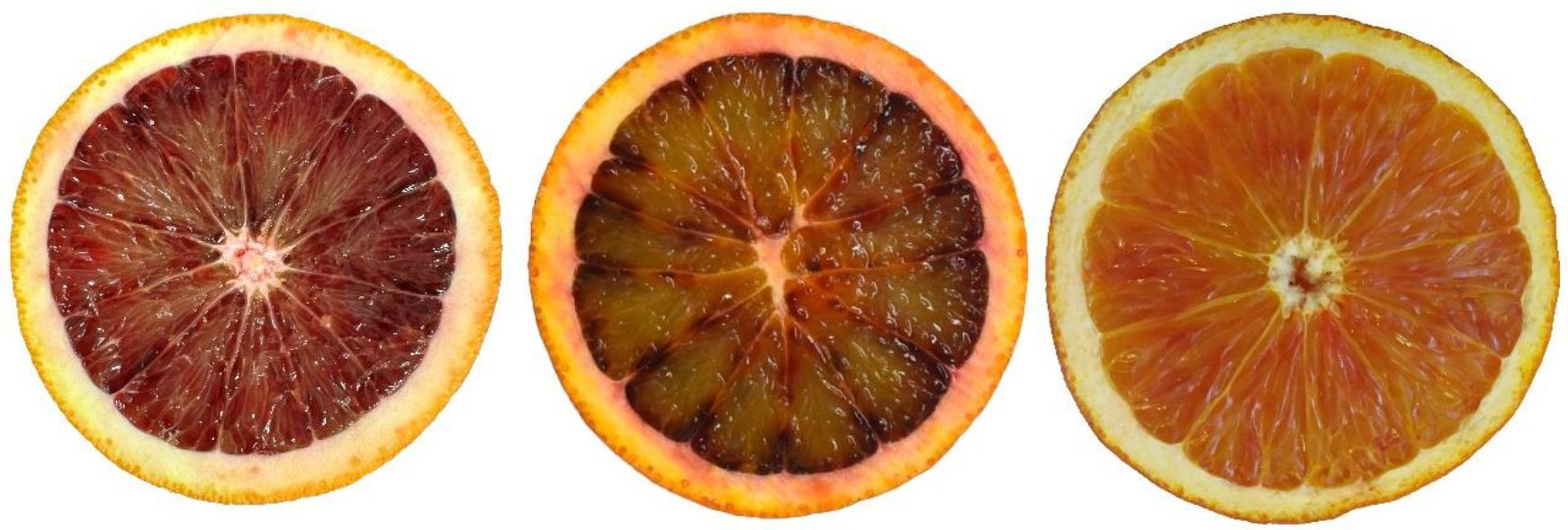

Anthocyanins are natural pigments that belong to the flavonoid family. Anthocyanin biosynthesis occurs through the phenylpropanoid pathway on the cytoplasmic face of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This synthesis involves the activation of multi-enzyme complexes. The expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes in blood oranges is regulated by a transcriptional regulator gene named Ruby, which is activated by a retrotransposon insertion in response to cold stress. Thus, blood orange fruit develop their red color in response to cold weather in the winter, which is when the fruit matures on the tree. After being synthesized on the ER, the anthocyanins are transported to the cell vacuole, which prevents their oxidation by enzymes in the cytoplasm. The trend of anthocyanin accumulation in blood orange fruit over time is shown in Figure 3. Anthocyanin levels serve as a quality index for blood orange fruit due to their appealing appearance and the antioxidant activity from which the fruit derive their health benefits and properties. One of the primary differences between blood oranges and other oranges is the synthesis of anthocyanin pigment in the flesh and sometimes in the peel, along with distinct flavor variations (Figure 4). The anthocyanin levels in blood oranges depend on the cultivar, cultural practices, climate conditions, environmental conditions, rootstock, maturity stage, and harvesting time. The anthocyanin pigments of blood oranges begin accumulating in the vesicles closest to the segment membranes (Figure 5).

Currently, blood oranges are not commercially grown in Florida, primarily due to low anthocyanin pigment accumulation in fruit grown in subtropical and tropical regions (Figure 6). Florida, characterized by warm temperatures and high humidity, allows production of a wide range of citrus crops. It is limiting for commercial blood orange cultivars because of the resulting low anthocyanin content and pale flesh color. Therefore, in this publication, we will explore the potential for blood orange cultivation in Florida and discuss the opportunities and challenges faced by producers and the industry. We will provide recommendations and suggestions for improving the production and consumption of blood oranges in Florida, offering insights for growers, Extension agents and specialists, and researchers.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Required Climate Conditions for Blood Orange Cultivation

Blood oranges are most well adapted to Mediterranean climate conditions (Figure 7). They require warm temperatures during most of the growing season with a period of cooler temperatures in the winter as the fruit mature for maximum anthocyanin production and red fruit color development. Blood oranges develop their red flesh color best at temperatures between 46°F and 59°F (8°C to 15°C). They need about 15 to 30 days in this temperature range to achieve their maximum red color. Blood orange trees can suffer from cold damage if exposed to temperatures below 25°F (-4°C). Young trees are particularly vulnerable and can suffer significant damage or even death with a few hours of exposure. Mature trees might withstand short periods (i.e., a few hours) of such cold temperatures but can still suffer from damaged fruit and leaves. Prolonged exposure (i.e., more than a few hours) increases the risk of severe damage to any blood orange tree. Trees can tolerate temperatures up to 104°F (40°C) but may experience heat stress and reduced fruit quality if exposed to prolonged high temperatures. Additionally, blood oranges need a wide day/night temperature range to develop high anthocyanin levels in the flesh. Therefore, commercial cultivation of blood oranges in subtropical or tropical regions is restricted by low or negligible anthocyanin content at commercial maturity. Blood oranges require at least 6 to 8 hours of direct sunlight per day to thrive. They need full sun exposure to produce the best fruit color and flavor. Although they may tolerate partial shade, such conditions may produce fewer fruit with less red pigmentation. Adequate water is essential, especially during the fruit development stage. Blood oranges need well-drained soil that does not retain water and has a slightly acidic to neutral pH. Sandy loam or loamy soils are generally suitable.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Growing and Cultivation of Blood Oranges in Florida

Florida’s citrus industry is a significant sector, producing sweet oranges, grapefruits, lemons, limes, and various other citrus fruits. Blood oranges belong to sweet oranges and are suitable for growing in Florida, including those cultivars that can be harvested in December. Blood oranges can be marketed as fresh fruit, processed juice, or dried products. Blood oranges are typically grown in climates different from what Florida generally provides. Blood oranges are early to midseason (based on cultivar) types that will crop in Florida, and in cooler winters they will produce fruit with varying degrees of red coloration. Some of the cultivars that are suitable for Florida include ‘Tarocco’, ‘Moro’, and ‘Sanguinello’, which are known for their unique flavor and red flesh (Figure 8). Although blood orange trees can be grown successfully in various regions of Florida, fruit anthocyanin levels can be low or even nonexistent at the commercial maturity stage in some areas (Figure 9).

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Commercial Blood Oranges for Cultivation

‘Moro’, ‘Sanguinello’, and ‘Tarocco’ cultivars are prominently recognized as commercial types of blood oranges (Figure 10). Each of these is now represented by multiple clonal selections with distinctive traits, such as different seasons of maturity, pigmentation levels, fruit size and shape, and flavors. Distinct and desirable pomological characteristics of these cultivars are fruit size, rind thickness, and anthocyanin pigmentation in the flesh and peel. These commercial blood orange cultivars develop few seeds and maximize the juicy flesh. However, some seeds may still be present in fruit, depending on pollination and environmental factors. These cultivars plus the Florida cultivar, 'Budd Blood', are discussed below.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

‘Moro’

‘Moro’ cultivars are the earliest to harvest among the commercial blood oranges. They are the most commonly marketed blood oranges in the United States and originated in Italy (Sicily). According to the cultivar description by Hodgson in The Citrus Industry (1967), ‘Moro’ fruit have a medium to large size, a round or oval shape, a slightly furrowed base, and a flattened apex. Fruit have few or no seeds. The peel has a medium thickness and is moderately adherent and somewhat pebbled. At maturity, the peel has an orange color with a light-pink blush or red streaks at later stages. The flesh has a dark color and a good taste, and it is juicy. The tree grows to a medium size and strength, with a wide and round canopy and a high yield. ‘Moro’ is unique in that the flesh develops a red color early and strongly, from medium to dark, while the peel may have little to no red color. Therefore, ‘Moro’ does not show external color in some areas where the conditions are not suitable for color development. However, it always has much more internal color than any other blood orange cultivar. This variety is classified among the deepest-hued blood orange cultivars (Hodgson 1967).

‘Sanguinello’

‘Sanguinello’ cultivars, also known as ‘Sanguinelli’, are late-midseason blood oranges originating from Spain. ‘Sanguinello’ was discovered around 1929 as a limb sport of ‘Doblafina’ blood orange. Fruit are smaller compared to other blood orange cultivars. Fruit are round and ovate to slightly asymmetrical in shape, and they have few or no seeds. The compact, leathery peel has medium thickness, and the orange is often blushed with varied shades of red. The flesh is juicy and is divided into 8–10 segments by thin membranes. The intensity of internal pigmentation places this cultivar in the deep blood group. The tree is small to medium in size and spineless, with light-green foliage. It is known for its high productivity (Hodgson 1967).

‘Tarocco’

‘Tarocco’, thought to have arisen from a mutation of ‘Sanguinello’, produces seedless, medium to large, globular to round fruit. It is recognized as the sweetest and most flavorful among the blood orange cultivars. The soft flesh is juicy, and is divided into 10–12 segments by thin membranes. ‘Tarocco’ fruit tend to be tart, a result of relatively slow acid degradation combined with rapid fruit softening after some amount of storage. The flesh color of ‘Tarocco’ cultivars depends entirely on the clonal selection grown, and generally, its red pigmentation is not as pronounced as that of the ‘Moro’ and ‘Sanguinello’ cultivars. However, there are some more deeply pigmented ‘Tarocco’ cultivar selections. It has a thin peel, slightly blushed in red tones (Hodgson 1967).

‘Budd Blood’

This cultivar was developed in Florida in the late 19th century from a seedling of a Sicilian blood orange. ‘Budd Blood’ blood orange has a high tolerance to cold and heat and is vigorous and productive. ‘Budd Blood’ matures in the midseason, but its fruit do not develop the deep red coloration typical of blood oranges grown in cool climates; instead, the peel usually exhibits the typical yellow to orange color of Florida oranges. In Florida, it begins to show red flesh by December, with red coloration becoming more apparent in January.

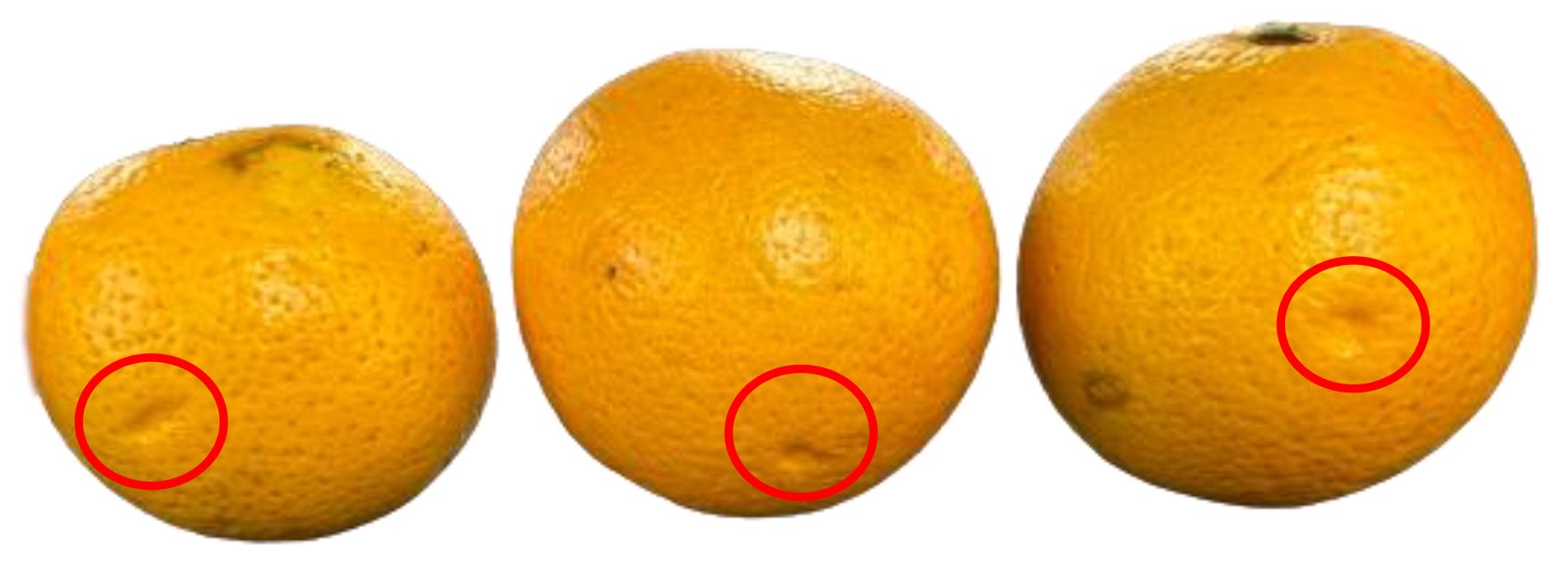

Harvesting

Generally, blood oranges can be harvested in December in Florida, depending on the cultivar and the climate. The fruit are ready to harvest when they reach the desired maturity index, color, and flavor. The fruit can be harvested by hand or by mechanical means such as clippers or shears. The fruit should be harvested carefully, avoiding any damage or bruising to the peel or the flesh (Figures 11 and 12). The fruit should be harvested with a short stem attached, and the stem end should be clipped to prevent puncturing of other fruit (Figure 13). The fruit should be sorted, graded, packed in clean and ventilated containers, and transported to the market or the processing plant and storage.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Consumption

Blood oranges can be consumed as fresh fruit, or processed into juice, wine, or dried products. Fresh fruit can be eaten as is or peeled and segmented for salads or desserts. Juice can be extracted from the fruit by hand or by machine and can either be consumed fresh or pasteurized and bottled for longer shelf life. Dried products can be made by using different drying methods, such as freeze-drying or dehydration, that remove the moisture from the fruit and extend its shelf life. Freeze-drying preserves more nutrients, color, and aroma of the fruit, but it is more expensive and time-consuming than dehydration. Dehydration is cheaper and faster, but it may cause some vitamin loss, browning, and shrinkage of the fruit. Dried products can be eaten as snacks or rehydrated and used in various recipes.

Challenges of Growing Blood Oranges in Florida

One of the main problems with growing blood oranges in Florida is that the climate is generally too warm for sufficient anthocyanin production (Figure 14). Florida has a humid subtropical climate in the north and central parts of the state, and a tropical climate in the south. The winters are mild and dry, with occasional cold snaps, which are not conducive to anthocyanin accumulation in blood oranges. Therefore, blood oranges grown in Florida usually have pale internal color and a low anthocyanin level at maturity and may not have the same health benefits as those grown in colder regions. To increase internal anthocyanin content, the fruit should be stored and kept on the tree after reaching commercial maturity. Another issue is the risk of freeze injury due to Florida’s propensity for occasional freezes. Blood oranges develop their best color in areas where long, hot, and dry summers are followed by cool nights in winter. While they can be grown successfully in certain areas of Florida, in regions prone to freezes, it may be necessary to protect the trees from frost or cold temperatures and to harvest the fruit regardless of maturity stage when a freeze is expected. Furthermore, citrus greening, formally known as huanglongbing (HLB), is a devastating disease that affects all citrus trees, including blood oranges. In Florida, it is associated with a bacterium that is transmitted by the Asian citrus psyllid. Citrus greening causes the leaves to turn yellow, the fruit to become bitter and deformed, and the tree to decline and become unproductive. In addition, adverse weather conditions, such as storms, hurricanes, or prolonged periods of rainfall, can impact citrus crops. Excessive rainfall can lead to root waterlogging or hypoxia, affecting root health and nutrient uptake. However, Florida’s favorable climate allows for a longer growing season. Furthermore, the market demand for locally grown produce and the unique niche of blood oranges can provide economic opportunities. With proper storage techniques, there is also potential to enhance the anthocyanin content, making Florida-grown blood oranges a viable and profitable option for farmers.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Approaches to Overcome Growing Challenges

There are a few possible approaches to overcome the challenges of growing blood oranges in Florida. Controlling citrus greening is challenging because there is currently no cure for the disease. However, there are several management practices that can mitigate citrus greening, including growing trees in insect-proof screen structures called CUPS (citrus under protective screen), or using HLB mitigation practices described in Ask IFAS publication PP-225, “Florida Citrus Production Guide: Huanglongbing (Citrus Greening).”

Protecting citrus trees from freezing temperatures or frost during winter is crucial for preserving their health and productivity. For more information about freeze protection of citrus trees, read Ask IFAS publication HS931, “Microsprinkler Irrigation for Cold Protection of Florida Citrus.”

Selecting appropriate rootstocks for grafting blood oranges can enhance fruit color by favoring expression of the genes involved in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway. The rootstocks C-35, Bitters, Carpenter, and Furr are most suitable for blood oranges because they significantly enhanced anthocyanin content in ‘Tarocco Scirè’ fruit. In another study by Morales et al. (2021), ‘Moro’ and ‘Tarocco Rosso’ blood oranges were grafted onto eight different rootstocks (Carrizo, C-35, Cleopatra mandarin, Citrus volkameriana, Citrus macrophylla, Swingle citrumelo, Forner-Alcaide 5, and Forner-Alcaide 13). Among these, fruit from trees on Swingle citrumelo and Volkamer lemon exhibited the lowest levels of anthocyanin, while fruit from trees grown on Cleopatra mandarin rootstock showed an increase in anthocyanin. Therefore, selecting a growing area with a history of appropriate environmental conditions and planting trees with appropriate rootstocks are both crucial for improving the chances of successfully producing high-quality blood oranges in Florida.

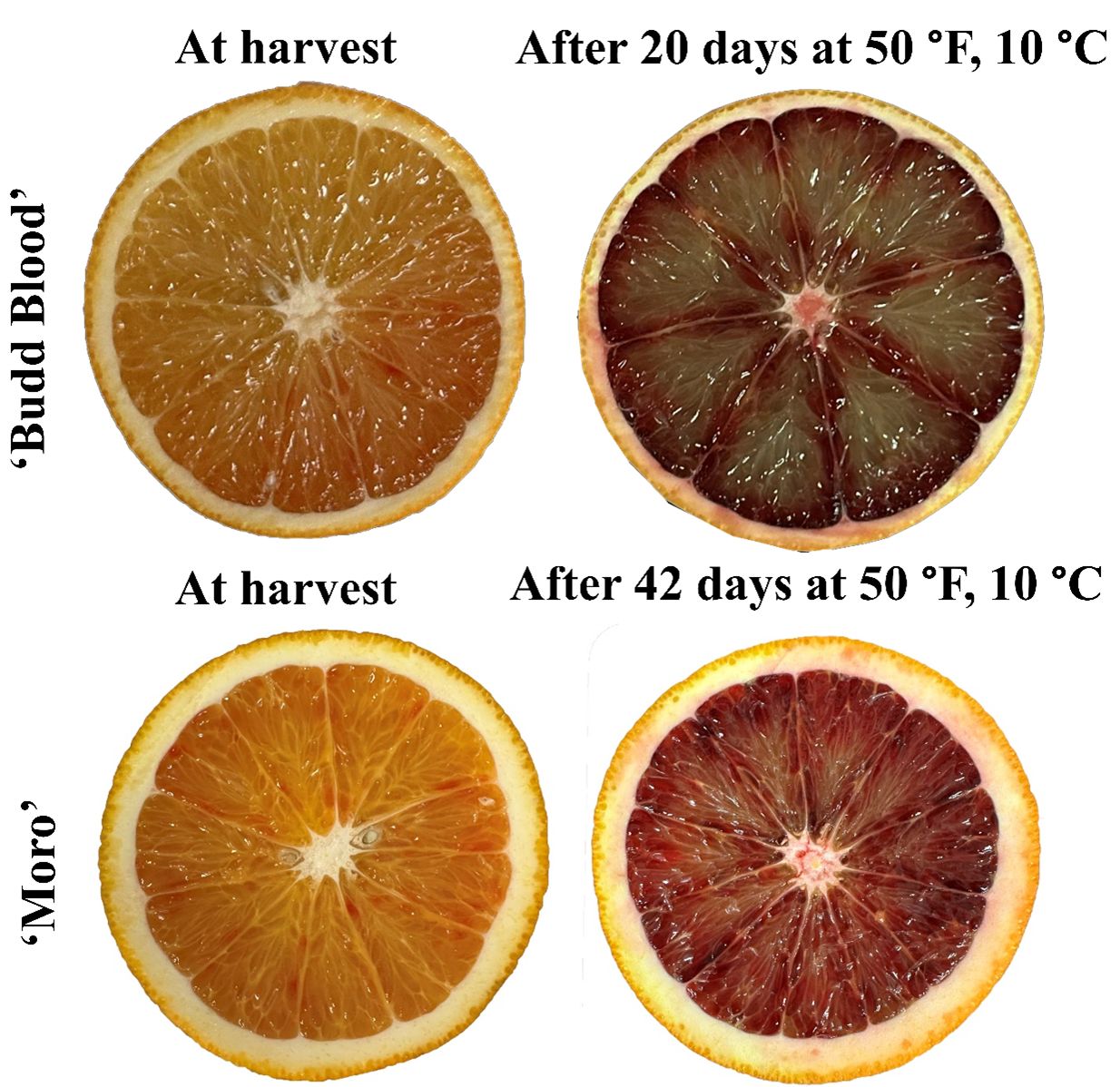

Furthermore, in blood oranges, some approaches can enhance anthocyanin production after harvesting. Postharvest exposure to cold storage temperatures can stimulate increased anthocyanin accumulation in blood oranges (Figure 15). The mechanism by which cold temperatures can enhance anthocyanins is stimulation of the enzymes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway. Interestingly, very low temperatures (1°C or 2°C) inhibit anthocyanin accumulation in blood oranges and induce chilling injury (Figure 16). It seems that exposure of blood oranges to very low temperatures leads to a severe decrease in cellular metabolism and downregulation of transcripts in the secondary metabolism pathways, such as those involved in the biosynthesis of anthocyanin. Research has shown that postharvest blood orange anthocyanin synthesis is maximally promoted by storage at 10°C (Habibi et al. 2024). Therefore, moderate postharvest temperature exposure can be used as a simple technique for enhancing anthocyanin accumulation in blood orange fruit.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Marketing and Price of Blood Orange

Blood oranges, while not commercially grown in Florida, can still be sourced from local markets, grocery stores, and farmers markets within the state. Additionally, they can be shipped to other states within the U.S. Blood oranges can be marketed as fresh fruit or as a juice product. The marketing strategy should consider the target market, consumer preferences, product quality (high anthocyanin level), differentiation, promotion, pricing, and distribution.

The price of blood oranges may vary depending on the season, the region, and the source. Generally, blood oranges are more expensive than other common oranges, such as navel or Valencia. Blood oranges grown in warmer climates, such as Florida, may have poorer flesh color and organoleptic qualities (flavor, lower sugar, and acid content) and may not provide the same health benefits as those grown in colder regions. This may affect the demand for and the price of blood oranges in different markets. It is better to keep blood orange fruit for 2 to 4 weeks in cold storage (50°F, 10°C) to enhance anthocyanin content, the effectiveness of which has been demonstrated in recent research at UF/IFAS (Figure 17) (Habibi et al. 2024). In addition, the price of blood oranges may fluctuate depending on the time of the year, the availability of different cultivars, and the availability of fruit from different regions. However, blood oranges may also offer more nutritional and health benefits than other oranges, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antidiabetic properties, because of their anthocyanin pigment. Therefore, blood oranges may be worth the extra cost for consumers who value their unique flavor and health benefits.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Further Reading

Caruso, M., F. Ferlito, C. Licciardello, M. Allegra, M. C. Strano, S. Di Silvestro, M. P. Russo, D. P. Paolo, P. Caruso, G. Las Casas, F. Stagno, B. Torrisi, G. Roccuzzo, G. R. Recupero, and G. Russo. 2016. “Pomological Diversity of the Italian Blood Orange Germplasm.” Scientia Horticulturae 213: 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2016.10.044

Dewdney, M. M., T. Vashisth, and L. M. Diepenbrock. 2023. “2023–2024 Florida Citrus Production Guide: Huanglongbing (Citrus Greening): CPG ch. 29, CG086/PP-225, rev. 6/2023.” EDIS. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cg086-2023

Habibi, F., M. E. García-Pastor, J. Puente-Moreno, F. Garrido-Auñón, M. Serrano, and D. Valero. 2023. “Anthocyanin in Blood Oranges: A Review on Postharvest Approaches for Its Enhancement and Preservation.” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 63(33): 12089–12101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2098250

Habibi, F., A. Ramezanian, F. Guillén, S. Castillo, M. Serrano, and D. Valero. 2020. “Changes in Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity, and Nutritional Quality of Blood Orange Cultivars at Different Storage Temperatures.” Antioxidants 9(10): 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9101016

Habibi, F., M. A. Shahid, T. Jacobson, C. Voiniciuc, J. K. Brecht, and A. Sarkhosh. 2025. "Postharvest Quality and Biochemical Changes in Blood Orange Fruit Exposed to Various Non-Chilling Storage Temperatures." Horticulturae 11(5): 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11050493

Habibi, F., M. A. Shahid, R. L. Spicer, C. Voiniciuc, J. Kim, F. G. Gmitter Jr., J. K. Brecht, and A. Sarkhosh. 2024. “Postharvest storage temperature strategies affect anthocyanin levels, total phenolic content, antioxidant activity, chemical attributes of juice, and physical qualities of blood orange fruit.” Food Chemistry Advances 4: 100722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focha.2024.100722

Hodgson, R. W. 1967. “Horticultural Varieties of Citrus.” In The Citrus Industry, Volume 1, edited by W. Reuther, H. J. Webber, and L. D. Batchelor. 431–591. Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Lee, H. S. 2002. “Characterization of Major Anthocyanins and the Color of Red-fleshed Budd Blood Orange (Citrus sinensis).” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 50(5): 1243–1246. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf011205

Modica, G., C. Pannitteri, M. Di Guardo, S. La Malfa, A. Gentile, G. Ruberto, L. Pulvirenti, L. Parafati, A. Continella, and L. Siracusa. 2022. “Influence of Rootstock Genotype on Individual Metabolic Responses and Antioxidant Potential of Blood Orange cv. Tarocco Scirè.” Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 105: 104246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2021.104246

Morales, J., A. Bermejo, P. Navarro, M. Á. Forner-Giner, and A. Salvador. 2021. “Rootstock Effect on Fruit Quality, Anthocyanins, Sugars, Hydroxycinnamic Acids and Flavanones Content during the Harvest of Blood Oranges ‘Moro’ and ‘Tarocco Rosso’ Grown in Spain.” Food Chemistry 342: 128305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128305

Oswalt, C., and T. Vashisth. 2023. “2023–2024 Florida Citrus Production Guide: Citrus Cold Protection: CPG ch. 20, CG095/CMG18, rev. 5/2023.” EDIS. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-cg095-2023

Talon, M., M. Caruso, and F. G. Gmitter Jr. (Eds.). 2020. The Genus Citrus. Duxford, UK: Woodhead Publishing.