Introduction

Muscadines (Muscadinia rotundifolia Michx) are vining grapes native to the southeastern United States. Unlike the more common European Vitis vinifera (common grapes) and American Vitis labrusca grape species that produce berries in bunches, muscadine grapes are borne in clusters of individual, large berries (Figure 1). In addition to their sweetness and unique flavor, muscadines are appreciated for their high concentrations of bioactive compounds, including anthocyanins, catechin, epicatechin, flavan-3-ols, kaempferol, myricetin, quercetin, ellagic acid, gallic acid, ellagitannins, and resveratrol, as well as dietary fiber, glycosides, and tannins. These compounds contribute to antioxidant activity and offer various health benefits to humans. The unique characteristics of muscadines make them valuable for both fresh consumption and processing, including juice, wine, jam, and freeze-dried snacks (Figure 2).

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Being indigenous to the region, muscadines are well-suited to Florida’s warm, humid climate. Muscadines possess significant resistance to environmental stresses, including heat, pests, and diseases, making them highly adaptable. Despite these benefits, muscadine production is also challenging due to limited consumer acceptance of the fruit’s thick peel and large seeds. Muscadine production in Florida is estimated to be over 1,000 acres, cultivating varieties for both fresh market and processing. EDIS Publication HS763, “The Muscadine Grape (Vitis rotundifolia Michx),” provides a thorough description of cultivars and production practices. Maintaining the postharvest quality of muscadine fruit for fresh consumption is crucial to maximizing the market potential of this crop.

Postharvest physiology plays a critical role in the storability and quality of muscadine fruit, as improper practices in handling, storage, and transport can lead to significant weight loss, softening, color changes, and a reduction in bioactive compound concentrations. Understanding the postharvest behavior and physiological disorders of muscadine fruit is essential for optimizing storage and extending shelf life. In addition, proper postharvest handling, including temperature management, packaging, and storage techniques, ensures that muscadines maintain their nutritional value and appeal to consumers, enhancing both their productivity and sustainability in the Florida agricultural industry. Thus, high-quality muscadines need advanced postharvest strategies to maintain fruit quality and ensure consumer satisfaction.

In this publication, we discuss the postharvest physiological responses and disorders of muscadine fruit, focusing on how handling practices, along with storage and transport conditions, affect fruit quality, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant activity. Our aim is to discuss effective postharvest practices that enhance the commercial viability of muscadine fruit and to identify strategies that reduce postharvest losses and improve the overall storability and quality of muscadine fruit. This publication provides valuable insights for growers, consumers, Extension agents, specialists, packers, and other relevant stakeholders.

Muscadine and Bunch Grape Differences

Muscadines differ from bunch grapes in that they have thicker skin (Figure 3), larger berry size, and a somewhat spicy-sweet taste. Muscadines are usually harvested as individual berries rather than in clusters (Figure 4). This is because the muscadine cluster is much smaller and has fewer berries than common grape bunches (Figure 5); also, the berries ripen unevenly in the muscadine cluster (Figures 6 and 7). Muscadine berries are individually harvested only after fully ripening. Overall, muscadines differ from bunch grapes in genetics, anatomy, physiology, and taste, so much so that they should be considered a separate fruit type.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

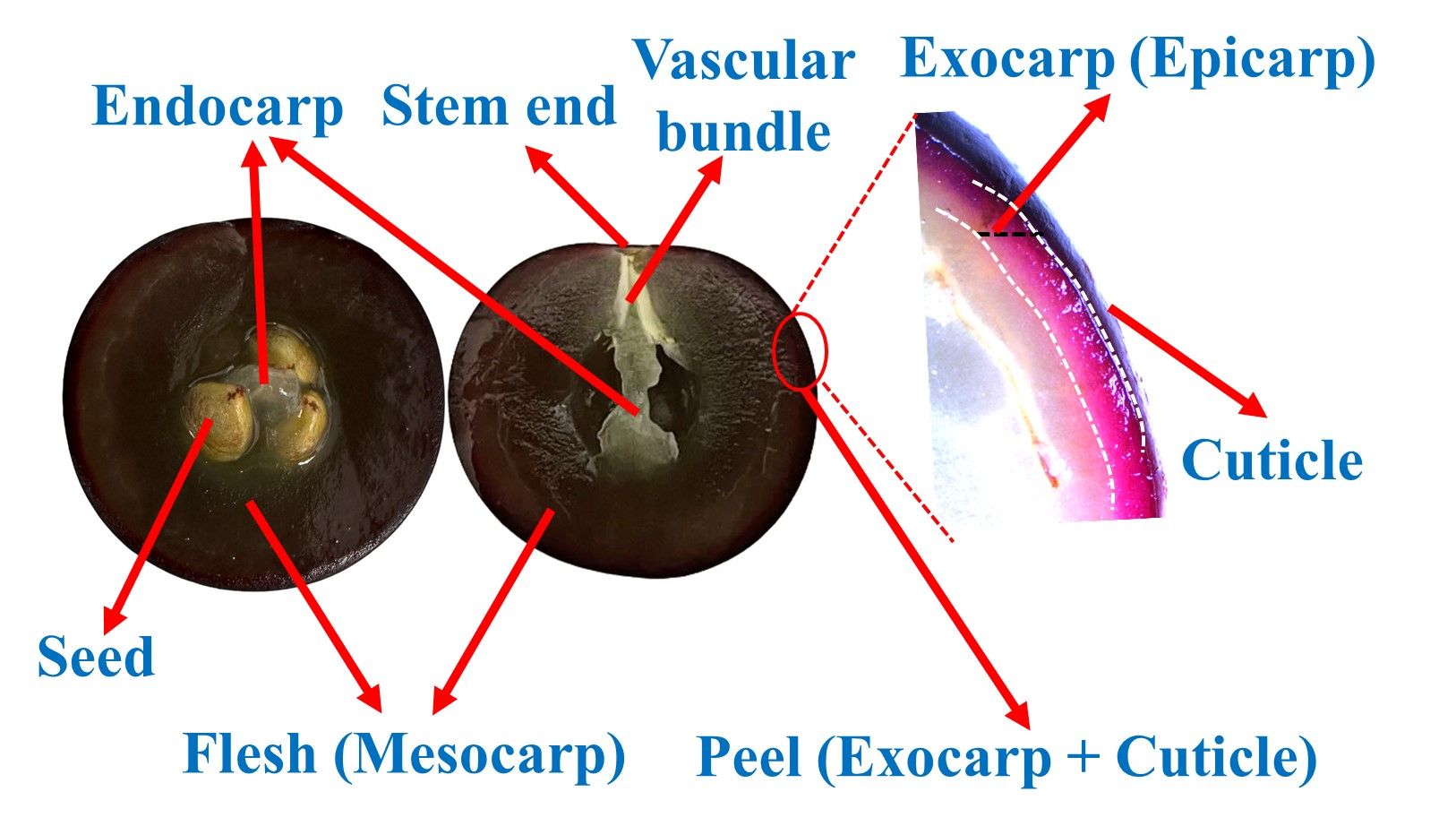

Anatomy of Muscadine Fruit

Understanding the anatomy of muscadine fruit helps to identify its different parts and structures. The muscadine fruit, botanically known as a berry, consists of several parts (Figure 8). Muscadine berries have a tough, leathery peel called the epicarp or exocarp, which can be bronze, red, or dark purple depending on the cultivar (Figure 9). The peel is covered by a layer of waxy material called the cuticle. Beneath the peel lies the fleshy mesocarp, which makes up most of the fruit’s volume. At the center of the fruit are up to five seeds, each surrounded by a hard, woody endocarp (Figure 10).

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Commercial Muscadine Cultivars

Commercial muscadine cultivars are specially bred to meet the demands of fresh fruit markets, wine production, and juice processing. ‘Noble’ and ‘Carlos’ are mainly used for wine production since they have high sugar content and juiciness (Figure 11). However, a wide range of muscadine cultivars are available, and some have better qualities for the fresh market, such as greater fruit size, firmer texture, and more appealing color range.

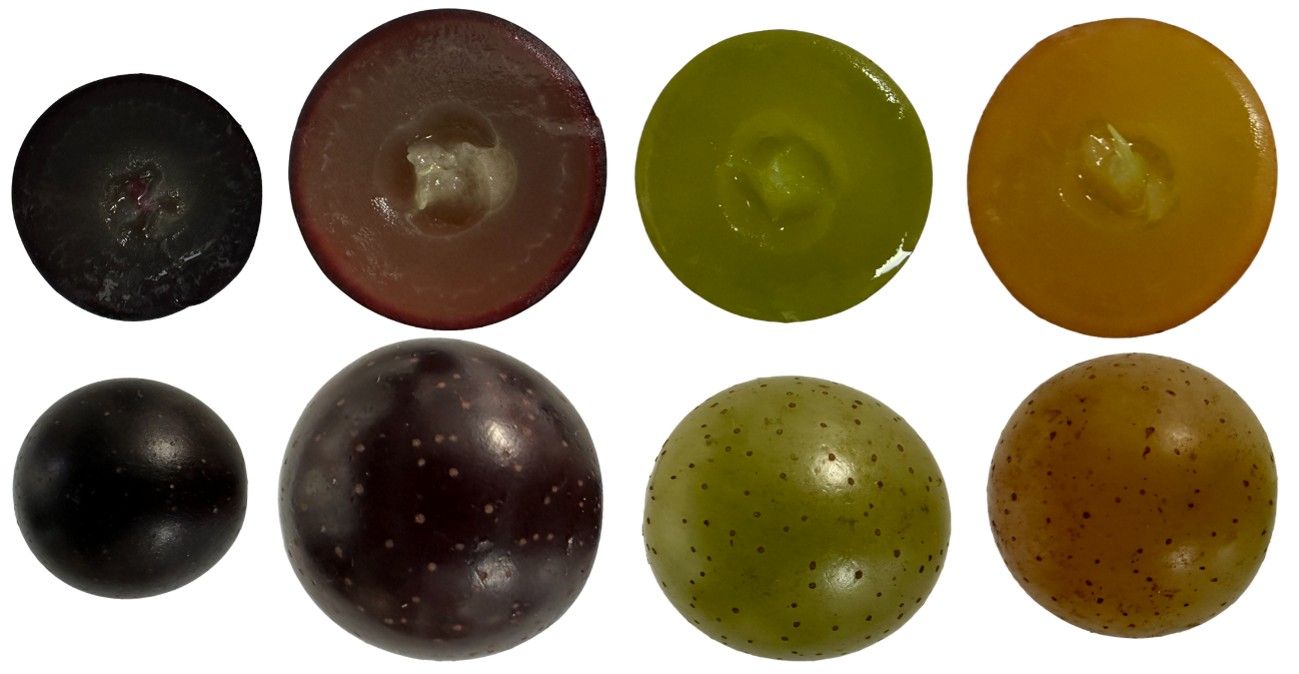

Muscadines are typically classified based on the color of their peel when ripe. Some purple cultivars, such as ‘Supreme’, ‘Paulk’, ‘Alachua’, ‘Nesbitt’, and ‘Lane’, possess a rich, dark hue. Some bronze cultivars are ‘Granny Val’, ‘Triumph’, ‘Fry’, ‘Hall’, ‘Tara’, ‘Late Fry’, and ‘Summit’. ‘Granny Val’, although considered a bronze cultivar, tends to remain green even when fully ripe (Figure 12). Red cultivars include ‘Scarlett’ and ‘Ruby Crisp’, showing the diversity and adaptability of muscadines for production. While most muscadine cultivars contain seeds, seedless cultivars such as ‘Oh My’ and ‘RazzMaTazz’ provide an additional option for fresh consumption, making them ideal for consumers seeking a seedless eating experience.

Due to the distinct pomological, physiological, and biochemical characteristics of muscadine cultivars (Figure 13), observing differences in postharvest physiological behavior is possible. This variability among cultivars enables producers and researchers to improve postharvest techniques, ensuring that each type can reach consumers with peak quality and extended shelf life, which ultimately enhances market value and reduces postharvest losses. Therefore, storage studies provide valuable insights for finding the optimal storage period for each cultivar in the market.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Storability of Muscadine Cultivars

The storability of muscadine cultivars depends on various factors, including genetics, physiological properties, and postharvest conditions. Muscadine cultivars exhibit significant variation in their capacity to maintain quality during storage. This characteristic is influenced by differences in berry maturity, peel thickness, fruit firmness, lenticel density, biochemical composition, and susceptibility to decay. Additionally, bioactive compounds, antioxidant levels, and moisture content play crucial roles in determining storability, thus impacting the fruit’s shelf life and nutritional quality. As examples of these variations, ‘Supreme’ and ‘Paulk’ maintain marketable quality longer than ‘Triumph’ and ‘Hall’ cultivars during long-term cold storage (Figure 14).

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Maturity and Harvesting

As a non-climacteric fruit, muscadines must be harvested at full ripeness since the berries do not continue to ripen once detached from the plant (Figure 15). As a result of their uneven ripening behavior, they must also be harvested individually. This makes hand-harvesting essential to pick each berry when fully ripe but before natural abscission. Fruit that have dropped to the ground are unsalable due to food safety risks from soil contact. While color development can indicate proper harvest maturity, measuring total soluble solids (TSS) content can also be used for this purpose; TSS content of ripe fruit typically ranges from 13% to 18%, as it relates to sugar accumulation (Figure 16).

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

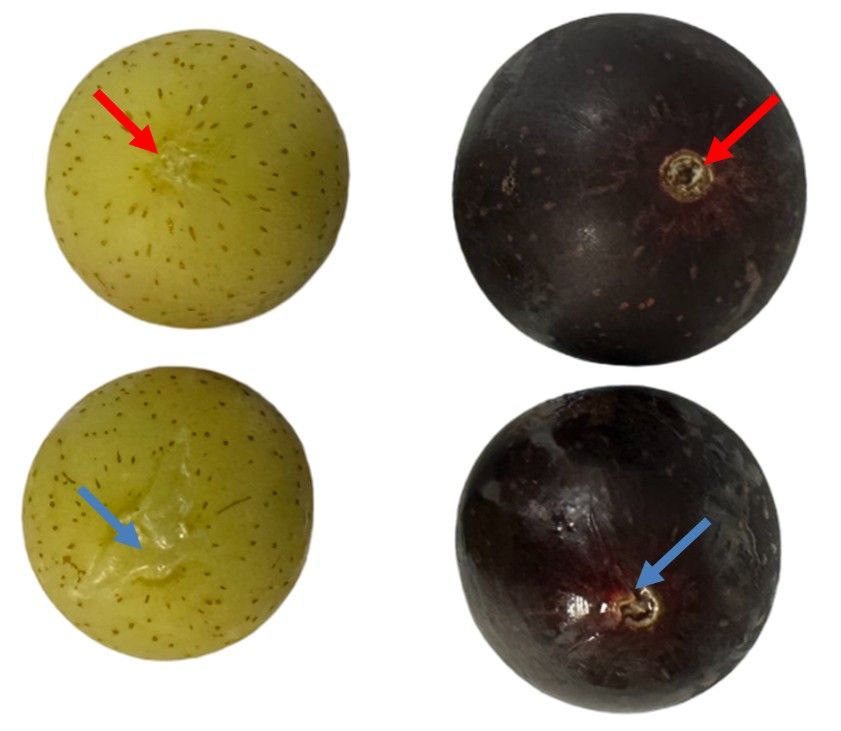

Stem Scar

When muscadines are harvested, the stem detaches at an attachment point on the fruit, creating one of two types of scars: wet or dry (Figure 17). A fully ripe fruit tends to detach cleanly at the abscission zone without tearing the peel, leaving a dry stem scar. Fruit with a dry scar are less prone to juice leakage and decay, making them better suited for storage and transport. A wet scar occurs when the abscission zone is not fully formed, which causes the peel to tear around the stem scar, leaving an open wound. This type of scar can lead to juice leakage and make the fruit more vulnerable to decay and spoilage during handling and storage. Selecting muscadine cultivars that are more likely to form a dry scar can help reduce postharvest issues and extend shelf life. For example, the ‘Granny Val’ cultivar tends to have the highest incidence of wet scars during harvesting, while ‘Paulk’ has the lowest.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Postharvest Problems and Physiological Disorders of Muscadine Fruit

Several postharvest challenges can significantly impact muscadine quality and marketability. A primary issue is the short shelf life of the berries at ambient temperatures, which restricts their availability and market reach. In addition, muscadines are prone to lose water, which affects their appearance and texture over time as the fruit shrivel and soften from loss of turgidity, making them less appealing to consumers.

Water Loss

In muscadines, cultivar-specific peel characteristics influence water loss during storage, leading to softening and shriveling (Figure 18). For instance, the water loss for ‘Supreme’ is lower than that of ‘Hall’ and ‘Triumph’. Factors such as cuticle thickness and lenticel density play significant roles in determining water vapor diffusion from the fruit surface. Cultivars with thicker cuticles and fewer or less prominent lenticels tend to experience reduced water loss, leading to lower weight loss during storage. For instance, the peel thickness of ‘Paulk’ and ‘Supreme’ is greater than that of ‘Hall’ and ‘Triumph’ (Figure 19). In addition, the lenticel density in ‘Hall’ is higher than that in ‘Supreme’ (Figure 20). To minimize water loss issues, maintaining a high relative humidity (RH) of 90% to 95% is essential, though this requires specialized equipment and can be costly. Rapid cooling after harvest also reduces water loss (forced-air cooled muscadines lose less water than those that are room-cooled) because the driving force for water movement from the berry tissue to the surrounding air is decreased when fruit and air temperatures are both lower.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

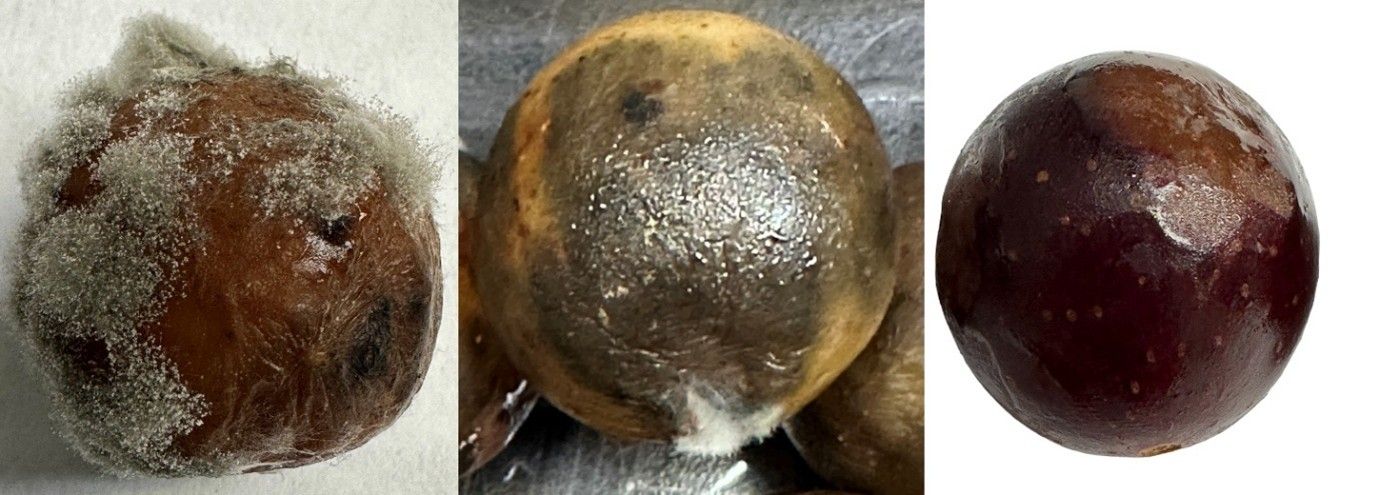

Postharvest Decay

Decay after harvest often develops in inadequately cooled muscadines, further reducing fruit quality and appeal (Figure 21). Muscadines are not usually washed or hydrocooled because they are very prone to spreading decay organisms and their spores, greatly increasing decay incidence. The primary pathogens responsible for significant postharvest losses in muscadines are all fungal. The three most important types of rot are ripe rot, bitter rot, and macrophoma rot, which are caused by the fungi Glomerella cingulata, Greeneria uvicola, and Botryosphaeria dothidea, respectively.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Physiological Disorders

Postharvest physiological disorders in muscadine fruit, such as chilling injury, contribute to significant losses in both fresh and processed markets. Chilling injury, characterized by brown or black discoloration of the peel, develops when muscadines are exposed to temperatures at or below 34°F (1.1°C) for periods longer than three weeks (Himelrick 2003; Smittle 1990).

Postharvest Treatments to Extend the Shelf Life of Muscadine Fruit

Due to their non-climacteric nature, muscadines cannot ripen after harvest and, therefore, must be harvested fully ripe, making them highly perishable and requiring careful handling and storage. Appropriate postharvest techniques and treatments are essential for extending shelf life, reducing decay, and preserving fruit quality, thereby enhancing marketability. Effective approaches increase storability, prolong market availability, and minimize deterioration. Understanding these methods is crucial for both consumers and producers, as they significantly extend storage life and market reach.

Temperature Management

As fully ripe fruit at harvest, muscadines have a short shelf life and are prone to postharvest losses at ambient temperatures due to decay, water loss, and physiological disorders. Such conditions accelerate senescence (aging), promote fungal growth, and further reduce fruit quality. Cold storage is the most effective method for extending the postharvest life of muscadine fruit, and this begins with removing field heat from muscadines as soon as possible after harvest. Warm fruit lose moisture at a much faster rate than cooled fruit, causing serious damage in appearance and, thereby, shortening shelf life. Picking muscadines early in the morning is recommended to minimize the accumulation of field heat.

For roadside marketing, in which small volumes of fruit are marketed a short time after harvest, there is less need to quickly cool the fruit to very low temperatures. In such a scenario, fruit quality can be maintained for two to three days by first cooling the fruit in a refrigerator or refrigerated storage room at 45°F to 50°F (7.2°C to 10°C), then packing them in plastic bags and keeping the RH high (90% to 95%) to reduce water loss.

For larger commercial operations, muscadines are typically packaged in 1-pound, vented clamshell containers, which facilitate quick cooling while offering protection during handling and storage (Figure 22). They can also be room cooled by placing them into a cold storage room that is maintained at 35°F to 40°F (1.7°C to 4.4°C) and 90% to 95% RH within a few hours after being harvested. Maintaining 95% RH in the cold room, however, will require a supplemental humidification system (a mister).

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

For maximum shelf life, muscadine handlers should strive to remove about 7/8 of the field heat from the fruit within two to four hours after harvest. This rate of rapid cooling is not possible using room cooling but can be achieved using forced-air cooling. Compared to room cooling, forced-air cooling reduces the cooling time from 24 or more hours to only 1 to 2 hours. Forced-air cooling accomplishes this rapid cooling rate by arranging a fan and a tarp so that when the fan is running, the only way for the cold room air to reach the fan is by drawing it through the vented containers of fruit. This more efficiently removes the heat by facilitating better contact between the cold air and the warm fruit. Forced-air cooling systems can be designed for handling operations of different scales, from portable systems for cooling single pallets of fruit to large systems capable of simultaneously cooling numerous pallets (Figure 23).

Credit: Jeffrey K. Brecht and Mark Ritenour, UF/IFAS

After cooling, the fruit can be held in cold storage as low as 35°F (1.7°C) without inducing chilling injury; keeping high RH (90% to 95%) is recommended to minimize water loss without promoting mold growth. Together, these conditions effectively preserve quality and extend the storage life of muscadines. Non-optimal storage temperatures, humidity levels, and storage durations can negatively impact the quality of muscadines, leading to visual deterioration and a reduced shelf life (Figures 24 and 25). For instance, muscadines last around 28 days at 39.2°F (4°C) but only 4 days at 68°F (20°C). Therefore, maintaining constant temperature and RH conditions during cold storage and distribution, without rewarming periods, is the most effective practice to extend fruit quality for consumer markets.

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Fariborz Habibi and Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

For more information on postharvest temperature and humidity management, refer to Sargent et al. (2007) and Watson et al. (2019).

Controlled and Modified Atmosphere (CA and MA) Storage and Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP)

Controlled and modified atmosphere (CA and MA) storage work by adjusting gas levels at low storage temperatures, particularly lowering oxygen (O2) and increasing carbon dioxide (CO2), to further slow metabolic processes and extend freshness beyond what can be achieved with low temperatures alone. The two technologies differ in that CA utilizes active feedback control of the atmosphere, while MA relies on balancing fruit respiration with storage chamber gas exchange rates.

Reduced O2 levels slow down the fruit’s respiration rate, reducing metabolic activity. Elevated CO2 levels help prevent decay due to its fungistatic effect. Muscadines can tolerate high CO2 levels (up to 30%) in postharvest storage, with CA and MA conditions maintaining fruit quality and reducing decay more effectively than normal air storage for up to 42 days at 39.2°F (4°C) (Shahkoomahally et al. 2021). However, a concentration of only 6% CO2 is sufficient to maximize decay control. Meanwhile, low O2 levels are relatively ineffective against decay organisms despite being tolerable for the berries. CA and MA also reduce the susceptibility of muscadines to chilling injury, allowing the fruit to be stored at lower temperatures for longer durations. Muscadines stored in CA with 5% O2 and 15% CO2 at temperatures between 34°F and 36°F (1.1°C and 2.2°C) show good preservation up to six weeks. Muscadines show significantly less decay when stored in vented plastic clamshell packages wrapped in polyethylene bags.

Modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) is an alternative to CA storage that extends the storage life of muscadine fruit. Like MA storage, a properly designed MAP system incorporates semi-permeable film to establish a beneficial gas equilibrium inside the package by regulating the diffusion of O2 into the package and CO2 out of the package to balance the fruit respiration rate. When muscadines stored in one MAP system equilibrated to about 12% O2 and 4% CO2 at 39.2°F (4°C), the fruit had lower decay, improved firmness, and better color retention for up to 28 days compared with fruit stored in normal air (Khalil et al. 2024). Even after 42 days, the muscadines in MAP had significantly lower decay, while biochemical attributes remained unaffected.

Other Treatments

Sodium Bisulfite

According to Smit et al. (1971), sodium bisulfite was added to some packages to release fungicidal sulfur dioxide (SO₂), which proved effective in extending the shelf life. Cellophane packaging coated with sodium bisulfite maintained acceptable fruit quality for up to two months at 32°F (0°C). In contrast, fruit stored in vinylidene chloride-vinyl chloride copolymer and polyethylene bags developed undesirable off-flavors and slight bleaching within two weeks (Smit et al. 1971). Tartrate precipitation, particularly on the peel, was more prominent during extended storage in these two types of bags, indicating material-dependent variations in fruit quality preservation.

Chlorine

Sanitizing fruit with chlorinated water at 100 ppm, with the pH adjusted to between 6.5 and 7.0, is a practice sometimes employed just before the transport and storage of muscadines to help reduce microbial contamination and extend shelf life. Muscadines are not typically rinsed or washed because getting the fruit wet can exacerbate the spread of fungal decay organisms. However, if washing or rinsing is desired, including chlorine or another food-grade sanitizer in the water is highly recommended to reduce cross-contamination of sound fruit with the fungal cells and spores from infected fruit. Adjusting the pH to 6.5 to 7.0 using citric acid or another food-grade acidulant is important when using chlorine to maximize the amount of the hypochlorous acid form of chlorine, which is the most effective chemical form from a fungicidal standpoint (Ritenour et al. 2002).

Combination Treatments

Combining low-temperature storage with some combination of selective packaging materials (i.e., MAP), SO₂ treatment, and chlorine offers a promising approach to extend the postharvest life of muscadines while minimizing quality degradation. This approach has the potential to greatly expand the possible marketing area for muscadines outside of Florida. Further research is encouraged to optimize these methods for commercial application.

Summary

Muscadines are a unique fruit crop with distinct characteristics that lend to their high perishability. Therefore, managing postharvest physiology is essential for reducing losses and preserving the fruit’s nutritional and sensory attributes. Temperature control remains the most critical factor in extending quality; rapid cooling techniques such as forced-air cooling are highly effective in slowing down respiration and delaying the onset of decay. Additionally, the use of packaging technologies like MAP can help maintain fruit firmness, color, and flavor during storage and transportation. The physiological responses of muscadines to postharvest stresses also vary by cultivar, emphasizing the importance of tailored postharvest strategies. Moreover, when used appropriately, chemical treatments or natural alternatives can offer additional protection against microbial spoilage. By integrating these technologies and understanding the biological responses of muscadines, growers and handlers can significantly enhance postharvest life and reduce waste. Consumer demand for muscadines continues to grow, especially due to their health-promoting properties, making effective postharvest management increasingly vital to ensure consistent quality from farm to market. Continued research and Extension efforts will further support sustainable practices and innovation in muscadine production and handling.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Research Capacity Fund (Hatch) projects, project award no. 7004457, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (FDACS) Viticulture program.

Further Reading

Andersen, P. C., A. Sarkhosh, D. Huff, and J. Breman. 2020. “The Muscadine Grape (Vitis rotundifolia Michx): HS763/HS100, rev. 10/2020.” EDIS 2020 (6). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs100-2020

Ballinger, W. E., and W. B. Nesbitt. 1982. “Quality of Muscadine Grapes After Storage with Sulfur Dioxide Generators.” Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 107 (5): 827–830. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.107.5.827

Habibi, F., J. K. Brecht, and A. Sarkhosh. 2025. “Impact of Muscadine Genotype on Postharvest Fruit Quality and Storability.” South African Journal of Botany 176: 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2024.11.025

Habibi, F., C. Voiniciuc, P. J. Conner, et al. 2024. “Nutritional Value of Peel and Flesh of Muscadine Genotypes: A Comparative Study on Bioactive Compounds, Total Antioxidant Activity, and Chemical Attributes.” Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 18: 3300–3314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-024-02404-1

Hickey, C. C., E. D. Smith, S. Cao, and P. Conner. 2019. "Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia Michx., syn. Muscandinia rotundifolia [Michx.] Small): The Resilient, Native Grape of the Southeastern US.” Agriculture 9 (6): 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9060131

Himelrick, D. G. 2003. “Handling, Storage and Postharvest Physiology of Muscadine Grapes: A Review.” Small Fruits Review 2 (4): 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1300/J301v02n04_06

Khalil, U., I. A. Rajwana, K. Razzaq, S. Singh, A. Sarkhosh, and J. K. Brecht. 2024. “Evaluation of Modified Atmosphere Packaging System Developed Through Breathable Technology to Extend Postharvest Life of Fresh Muscadine Berries.” Food Science & Nutrition 12 (5): 3663–3673. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.4037

Ritenour, M., S. A. Sargent, and J. A. Bartz. 2002. “Chlorine Use in Produce Packing Lines: HS761/CH160, 11/2002.” EDIS 2002 (7). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ch160-2002

Sargent, S. A., M. A. Ritenour, J. K. Brecht, and J. A. Bartz. 2007. “Handling, Cooling and Sanitation Techniques for Maintaining Postharvest Quality.” HS719. University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. EDIS. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00001676/00001

Sarkhosh, A., F. Habibi, and S. A. Sargent. 2023. “Freeze-Dried Muscadine Grape: A New Product for Health-Conscious Consumers and the Food Industry.” EDIS 2023 (4). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-HS1468-2023

Sarkhosh, A., F. Habibi, S. A. Sargent, and J. K. Brecht. 2024. “Freeze-drying does not affect bioactive compound contents and antioxidant activity of muscadine fruit.” Food and Bioprocess Technology 17 (9): 2735–2744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-023-03277-w

Shahkoomahally, S., A. Sarkhosh, L. M. Richmond-Cosie, and J. K. Brecht. 2021. “Physiological Responses and Quality Attributes of Muscadine Grape (Vitis rotundifolia Michx) to CO2-Enriched Atmosphere Storage.” Postharvest Biology and Technology 173: 111428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2020.111428

Smit, C. J. B., H. L. Cancel, and T. O. M. Nakayama. 1971. “Refrigerated Storage of Muscadine Grapes.” American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 22 (4): 227–230. https://doi.org/10.5344/ajev.1971.22.4.227

Smittle, D. 1990. “Requirements for Commercial CA Storage of Muscadine Grapes.” Proceedings of the Viticultural Science Symposium. Florida A & M University.

Walker, T. L., J. R. Morris, R. T. Threlfall, G. L. Main, O. Lamikanra, and S. Leong. 2001. “Density Separation, Storage, Shelf Life, and Sensory Evaluation of ‘Fry’ Muscadine Grapes.” HortScience 36 (5): 941–945. https://doi.org/10.21273/hortsci.36.5.941

Watson, J. A., D. Treadwell, S. A. Sargent, J. K. Brecht, and W. Pelletier. 2019. “Postharvest Storage, Packaging and Handling of Specialty Crops: A Guide for Florida Small Farm Producers: HS1270, 10/2015.” EDIS 2016 (1). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-hs1270-2015