Arthropod parasites of horses include internal bots that infest the digestive tract, mites that burrow in the skin and feed on the skin surface, ticks that infest the ears as well as the skin, lice that either suck blood or feed on skin, blood sucking flies, and mosquitoes that range in size from biting gnats just observable with the naked eye to the large black horse flies which are almost one inch long. Non-biting flies such as house flies are also important in producing fly worry and disease transmission.

These parasitic habits are complicated by damage caused by disease transmission and severe host reactions caused by an immune response.

Signs of damage usually show up as weakness, emaciation, anemia, rough hair coat, stunted growth, tail and mane rubbing, lesions, and disease transmission. Extreme populations or transmission of disease may lead to death of the host.

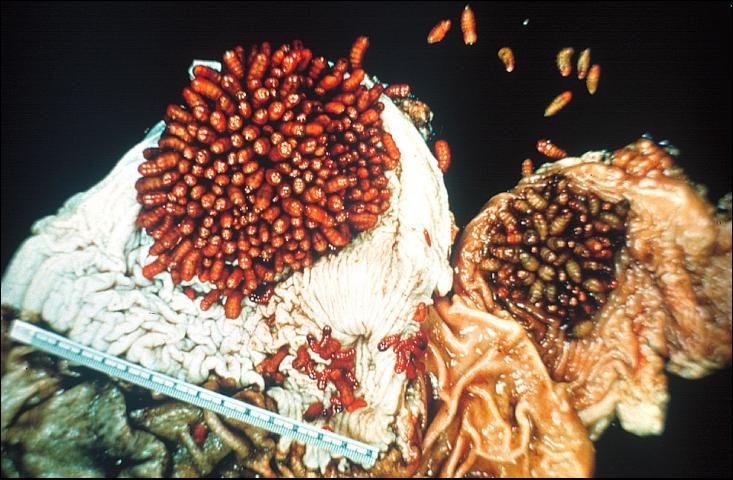

Horse Bots

Horse bots (Figure 1) are bot fly larvae and are internal parasites of horses. The horse bot larvae develop in the stomach of horses causing symptoms ranging from stomach ulcers and esophageal paralysis to occlusion of the digestive tract.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Biology

The adult bot fly (Figure 2) is a bee-like fly about 1/2 to 3/4 inch in length. Bot flies are covered with black and yellow hairs and do not feed as adults. In Florida two species of adult bot flies may be active throughout the year, although they are more abundant from late spring to early winter.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Female bot flies lay from 150 to 1,000 yellowish eggs. The eggs are firmly glued to the hairs of the forelegs, belly, flanks, shoulders, and other parts of the body of the horse. While the fly's egg laying does not cause the horse pain, the horse often is bothered by presence of the fly.

Egg laying principally occurs on the inside knees of the animal where the horse can easily reach the eggs with its tongue. The eggs are ready to hatch 7 to 10 days after oviposition and will hatch only if the horse licks or bites the area where they have been glued. It is believed that the sudden increase in temperature from the tongue stimulates the young larvae to hatch. Warm, moist grooming cloths may also cause eggs to hatch and present a hazard of infestation to the individual grooming the animal.

Once inside the horse's mouth, the larvae burrow into the mucous linings of the mouth and tongue and remain there for 3 to 4 weeks. Damage to the mouth membranes is often seen during this stage. From the mouth, the larvae pass to the stomach and intestine where the second and third instar larvae remain attached but may change location. They remain in these areas until the following summer.

When fully mature, the third stage larvae detach from the stomach, pass through the intestines and are passed in the droppings. They migrate out of the droppings and burrow under the surface of the soil. Here the pupae remain for 1 to 2 months. The adult fly emerges throughout the spring, summer and fall.

The adult fly does not feed but immediately starts its egg laying cycle, which lasts for about two weeks, after which the fly dies. Cold weather and frost usually kill off the remaining flies in the fall of the year and signal the end of the egg laying season. Only one generation is completed per year.

In south Florida, adult bot flies have been found to be active year-round. In central and north Florida adults are found from spring to early winter. Highest populations of adults are recorded from August through September. Larval populations sampled in horses in October and November ranged from 1 to 184 larvae per stomach in central and north Florida.

Symptoms

A few bots will cause little damage; however, increasing populations cause gastrointestinal disturbances. Infestations can produce symptoms varying from mild to severe. Symptoms include irritation of stomach membranes, ulceration of the stomach, peritonitis, perforated ulcers, colic, mechanical blockage of the stomach resulting in stomach rupture, esophageal paralysis, and squamal cell tumors.

In addition to the previous pathogenicity, first stage larvae migrating in the tongue and gums have been shown to cause pus pockets in the mouth. The larvae developing in the stomach have also been shown to cause severe anemia.

Cases have also been reported of horse bots in humans. The first stage larvae have been found migrating in the skin of humans (cutaneous myiasis) and in the eye, causing severe damage. Horse bots have also been reported in the stomach of humans and pig.

Control

Effective control of horse bots requires breaking the life cycle of the fly. Insecticides are labeled for external treatment using warm water wash. This must be done after eggs have been laid but before they hatch. For external insecticide treatment, a warm water wash (110°F–120°F) should be rubbed or sponged on areas infested with eggs. The larvae will hatch and die from contact the insecticide. Treatments should be applied weekly during peak oviposition periods (August–September). During the wash, care should be taken to protect hands from both insecticide and larvae with synthetic rubber gloves. Grooming may aid in removal of eggs but effectiveness of control is questionable.

For internal treatment of horse bots, consult a veterinarian. Insecticides are labeled as liquids, bolus, and feed additives for horse bot control. Internal medications will usually control second stage but may not control third stage larvae. Most effective treatments should be applied to control second stage larvae one month after first sighting of eggs. Materials that control both second and third stage larvae should be applied in the fall of the year. Carbon disulfide is effective but may cause gastritis with sloughing of stomach mucosa.

Horse and Deer Flies

Horse flies (Figure 5) and deer flies (Figure 6) are insects that are usually daytime feeders and are vicious biters and strong fliers. As with mosquitoes, only the females bite. Their attacks often account for lowered weight gains and reduction in condition.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Credit: James Castner, UF/IFAS

Because of their painful bites and frequent attacks, horse flies produce frenzied behavior in their hosts, sometimes causing them to run long distances in an effort to escape. Horse flies introduce an anticoagulant into the bite wound, which causes blood to ooze for up to eight hours. These wounds are excellent sites for secondary invasion of screwworm and also cause much blood loss. Being intermittent feeders, they are known mechanical transmitters of diseases such as anthrax, tularemia, anaplasmosis, and equine infectious anemia (EIA).

Most species of horse and deer flies are aquatic or semi-aquatic in the immature stages, but some develop in moist soil, leaf mold, or rotting logs. Generally the eggs are deposited in layers on vegetation, objects over water, or moist areas favorable for larval development.

Eggs hatch in 5 to 7 days and the larvae fall to the surface of the water or moist areas where they begin to feed on organic matter. Many species prey upon insect larvae, crustacea, snails, and earthworms.

When the larvae are ready to pupate, they move into drier soil, usually an inch or two below the surface. The pupal stage lasts 2 to 3 weeks, after which the adults emerge. The life cycle varies considerably within the species, requiring anywhere from 70 days to 2 years.

Control of these flies is difficult with no treatment of the larvae possible. Repellents will give relief for up to 24 hours when applied to the animal.

Other Biting Flies

Stable Flies

The stable fly (Figure 7), is similar to the house fly in size and color, but the bayonet-like mouthparts of the stable fly differentiate it from the house fly. Unlike the flies already discussed, both sexes of the stable fly are vicious biters. They are strong fliers and range many miles from the breeding sites.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Stable flies cause irritation and weakness in animals and account for much blood loss in severe cases. Bite wounds also can serve as sites for secondary infection and scar tissue formation. These flies are easily interrupted in feeding and are mechanical transmitters of anthrax, equine infectious anemia (swamp fever), anaplasmosis, and Habronema stomach worms.

Stable flies breed in soggy hay, grain or feed, piles of moist fermenting weed or grass cuttings, spilled green chop, peanut litter, seaweed deposits along beaches, and in manure mixed with hay.

The female, when depositing eggs, will often crawl into loose material, placing the eggs in little inner pockets. Each female may lay a total of 500 to 600 eggs in four separate layings. Eggs hatch in 2 to 5 days and the newly hatched larvae bury themselves, begin to feed, and mature in 14 to 26 days. While the average life cycle is 28 days, this period will vary from 22 to 58 days, depending on weather conditions.

Adult flies are capable of flying more than 90 miles from their breeding site. If more than 5 to 10 flies are present per animal extensive fly rearing is present in the area. Stable flies visit the animal only to feed, spending 80% of their time away from the animals.

Stable fly control is most successfully approached with cultural control measures. Since the larvae require a moist breeding media, it is essential that the breeding source be found and dispersed to allow drying. Animal treatments are limited to fogging or mist applications of insecticide and the use of repellents, which may last for 2 to 3 days. Insect traps are becoming more useful in reducing insect numbers. Check with your local UF/IFAS Extension agent on their use.

Sand Flies and Biting Midges ("Punkies, No-See-Ums")

Other blood sucking flies that are often problems to cattle and horses include many species of Phlebotomus flies, sand flies (Leptoconops and Culicoides) (Figure 6), and biting midges ("punkies, no-see-ums"). All of these flies are associated with wet or aquatic habitats. Because the areas are so often associated with water or swampy conditions these pests become a problem that is difficult, if not impossible to control. Several species of sand flies and biting midges are of economic importance on livestock.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

The life cycles and habits of midges affecting livestock is poorly known. The biting midges are considered the most important livestock pests of this group. One species is a known vector of bluetongue virus in sheep and cattle. Damage is usually seen in skin reactions and lesion formation. Horses may lose their hair in the infected areas because of fly feeding. No effective control measures are available for these flies.

Black Flies

The black flies are small flies and are not as common in Florida as in other regions. Eighteen species are reported for Florida. Four species feed on cattle and horses. Damage from black flies feeding includes animal losses along the river basins. Death usually occurs as a consequence of an acute toxemia caused by vast number of bites or as a result of anaphylactic shock. Both weakness from heavy blood loss and suffocation by inhalation may also cause animal loss. Diseases are vectored by black flies in other regions of the world.

Black flies (Figure 9) are small, dark, stout-bodied flies with a hump-backed appearance. The adult females blood feed mainly during daylight hours and are not host specific. The black fly is a potential disease vector in Florida. It hovers about the eyes, ears, and nostrils of animals, often alighting and puncturing the skin with an irritating bite. Large numbers of bites may cause weakness from blood loss, anaphylactic shock, or death.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

The black fly life cycle begins with eggs being deposited on logs, rocks or solid surfaces in swiftly flowing streams. Larvae attach themselves to rocks or vegetation with a posterior sucker. The length of the larval period is quite variable depending on the species and the larval environment. The adults that emerge after pupation are strong fliers and may fly 7 to 10 miles from their breeding sites.

Horn Flies

Horn flies (Figure 10) often attack horses that are pastured near cattle. These blood-feeding flies do not develop in horse manure but migrate to horses from cattle pastures. They do feed on horses and may build to more than 65 flies per animal. In Florida they are common and persistent blood feeders causing damage by irritating the animal and producing skin lesions. The life cycle of the horn fly takes place only in fresh cattle manure. Eggs hatch in about 18 hours, and the larvae feed in the individual paddies, passing through three instars in 3 to 5 days. The pupal stage lasts 3 to 5 days and the adults which emerge have a preoviposition period of three days. Mating takes place on the host with females laying about 200 eggs in their lifetime.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

These flies apparently migrate extensively and will go to and stay on horses.

Control of horn flies on horses can be achieved with any of the residual treatments applied for insect control on horses.

Non-Biting Flies

The house fly (Figure 11) is of concern to both livestock producers and people who live around farmstead areas. The animal industry cannot raise animals without producing manure, which is the house fly's preferred breeding site. The house fly is found both inside stables and on the animals themselves. Flies can migrate from farms to any close residential areas. House flies are an immediate concern to the animal industry because they can be mechanical vectors of human and animal disease.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

House fly damage to horses is from annoyance caused by persistent feeding on the muzzle, eyes and open wounds. Animals become nervous, restless, and reduce food intake. House flies are also intermediate hosts for stomach worms (Habronema), diseases, and parasites of horses. It has also been shown that the house fly is capable of transmitting diseases such as bovine mastitis and pink eye. In addition house flies are known to be contaminated with more than 100 species of pathogenic organisms.

The house fly has complete metamorphosis, going through the egg, larva, pupa, and adult stages. The adult female searches for a suitable larval medium to lay eggs. Poultry and livestock manure, organic refuse (plant and animal), waste, garbage, and other filth is normally selected for oviposition. The adult female lays 75 to 150 oval, white eggs that hatch in 8 to 12 hours. The larval stage is composed of three larval stages lasting 3 days to 3 weeks. The pupal stage lasts 4 to 5 days after which the adult emerges. Thus in a minimum of 10 days, under optimum conditions, a house fly can develop from egg to adult.

Control of house flies is a continuing operation, in which sanitation and moisture control are the most important steps. Manure should be removed and disposed of every 4 to 5 days in summer and less frequently in cool weather. The ideal method of disposing of manure is to spread it on land where it can serve as fertilizer.

If flies continue to be a problem after sanitation and moisture control practices have been implemented it may be necessary to apply chemical control methods. Chemical controls may be applied as larvicides, baits, residual sprays, and space sprays.

Larvicides are chemicals applied to manure to kill house fly maggots. They are effective in reducing house fly breeding when applied thoroughly.

Baits are composed of an attractant material such as sugar and an insecticide. The flies are attracted to the bait and killed by the insecticide. Dry baits should be applied to hard dry surfaces so they will not dissolve and become ineffective.

Residual sprays are normally insecticides that are applied to surfaces flies frequently contact. These surfaces can be rafters, beams, structures or any place flies tend to rest.

Space sprays are effective in quickly knocking down adult flies. Because there is no residual effect, insecticides applied in this manner must be applied frequently.

The face fly is not presently in Florida. It is present in a corner of Georgia and Alabama and could migrate into Florida if it is able to adjust to our conditions. Its oviposition is similar to the horn fly. Its feeding habits on the host are similar to the house fly except it congregates at the eyes.

The face fly avoids shade preferring the open sunlight, which it the opposite of the house fly which is closely resembles. It causes severe irritation on the face and eyes and is very difficult to control.

Eye gnats (Figure 12) are very common small flies seen around the faces of horses throughout the summer months. The larvae develop in organic matter in the soil. No effective control methods are available for this pest.

Credit: J. L. Castner, UF/IFAS

At least 60 species of blow flies have been reported for North America. The primary screwworm fly is a true parasite; other blow flies and their larvae feed mainly on cadavers or they may invade necrotic wounds.

The blow flies (Figure 13) are most numerous in the spring and fall. In general eggs are laid in open wounds and putrid organic debris. The larvae develop by feeding on dead tissue or living tissue. As the larvae mature they fall out and pupate in the ground. About 17 days are required from egg to adult.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Adults may lay as many as 1,000 eggs in a lifetime in batches of 100 to 250. The primary screwworm has been eradicated by the sterile male method in the Southeast but is still present in Mexico and Central America and is always a potential threat.

Control is best achieved by proper care of injured animals and proper disposal of putrid organic debris.

Horse Lice: Biting and Sucking

Two biting lice and one sucking louse (Figure 14) infest horses and mules. Heavy infestations usually are seen in the winter and may cause anemia, unthriftiness, loss of condition, stunting of growth, uneasiness, loss of hair and even sores, wounds and scabs from rubbing.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Lice are permanent parasites of their hosts, spending the entire life cycle on the host. Most species live only a short time off the animal and are not found on other animal species. The horse sucking louse will only live for 2 to 3 days off the host. The life cycle for this louse takes 4 to 5 weeks for completion from egg to egg with 5 to 14 days required for egg hatch. Egg production for different species varies from 50 to 100 eggs. Lice are normally seen in damaging numbers in the winter and may be found anywhere on the body.

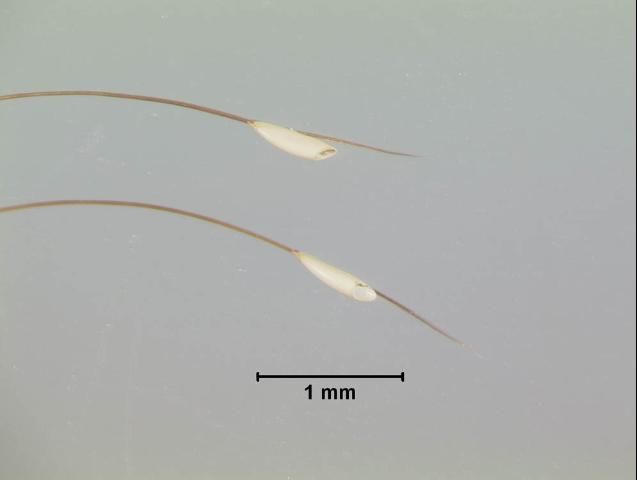

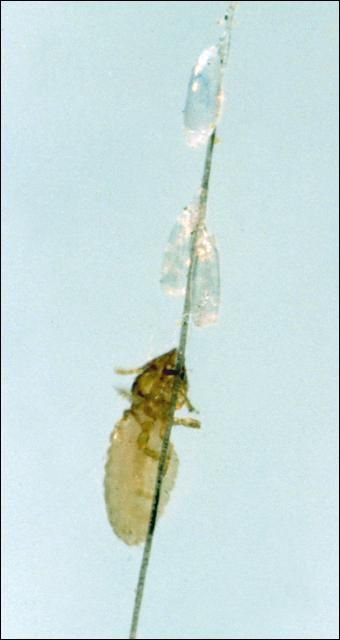

Biting lice (Figure 15) feed on the skin and hair causing itching, irritation, and hair loss. The life cycle for these lice takes 27 to 30 days for development from egg to adult and about seven days for the eggs to hatch. These lice are most prevalent on the head, mane, tail base, and shoulder area. These are usually winter parasites, however, they may be found in Florida in damaging populations at any time of the year.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Lice are transferred from animal to animal by contact, movement of flies, and occasionally by contaminated equipment and bedding. All animals should be checked periodically for infestations, and all animals in infested premises should be treated.

Retreatment of animals is required because insecticides will not kill the eggs. Effective control can be achieved with two weeks between treatments.

Mites: Skin Surface and Burrowing

Five different species of mange, scab, and itch mites attack horses. These mites are not usually prevalent in Florida; however, isolated infestations may become a problem. These must be controlled to prevent infestations on other horses in the herd as well as man.

These pests are too small to be seen with the naked eye but the host damage and reaction is easily recognized. The mites associated with horses belong to two basic groups. Itch, mange or scabies mites, and the chigger or follicle mites.

Itch or Mange Mites

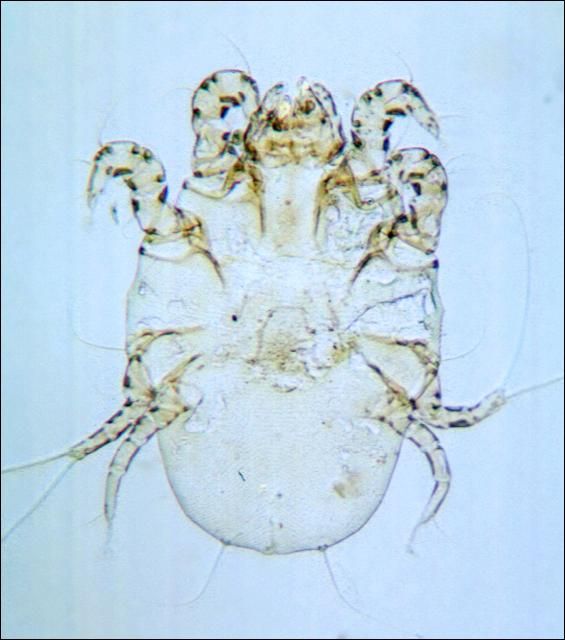

The itch, or mange, mites (Figure 16), are small ovoid mites about as big around as the cross section of a straight pin (1/16 inch). The eight legs are very short and barely extend beyond the margin of the body. They burrow just beneath the skin making very slender winding tunnels from 1/10 to 1 inch long. The fluid discharged at the tunnel openings dries to form dry nodules.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

The female mite dies after laying about 20 eggs in the tunnel. Eggs hatch in 3 to 10 days into microscopic 6-legged nymphs. These become 8-legged after one molt, and in two more molts they reach maturity. The males die after mating. The females begin new tunnels 10 to 30 days after hatching from eggs.

A generation can be completed in two weeks. These mites secrete an extremely irritating toxin, that when combined with the tunneling, causes extreme host reactions and itching. The host reaction causes the skin to slough off in the infested areas.

Mite problems are most prevalent during the winter but can persist throughout the year. Infestations are contagious and treatment of all animals in a herd is essential in preventing spread. Under certain conditions humans may become infested with this mite.

Infested animals rub and scratch continuously. Areas of the head, back, or base of the tail become inflamed and scurfy with only scattered hairs remaining. The infestation may spread over the entire body forming large, dry cracked scabs on the thickened skin. To distinguish it from lice, some scrapings from the margins of the affected skin should be examined for mites.

Mites that cause chorioptic mange are very similar to itch mites except they do not burrow into the skin. Chorioptic mites live and feed on the skin surface. The life cycle is similar to the itch mite with the production of lesions and mange in the areas of the hocks, knees and pasterns. They often produce foot mange. Infested horses are restless and are often seen biting or licking the lower legs. Severe infestations may cause lameness.

Demodectic Mites

The demodectic or follicular mite (Figure 17), is a microscopic (0.23mm), cigar-shaped, worm-like mite that lives within the skin. All stages of the life cycle are often found within the hair follicle and sebaceous glands. The mite causes nodular lesions in the skin usually around the neck and shoulders. Nodules can vary in size from a sixth of a match head to the size of a golf ball. The nodules form from a creamy fluid substance in which the mites are found.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Little is known of the life cycle of this mite. Control is difficult because of the depth of the mites in the skin.

Chigger Mites

Chigger mites (redbugs) (Figure 18) make up a large group of species which occasionally cause problems for both horses and man. They cause intense itching and reddish welts on the skin.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Adult chiggers do not feed on animals but are predators on eggs and other small arthropods. They lay eggs in the soil that hatch to the 6-legged parasitic "chigger" stage. These seek out a host. They attach to the skin and begin feeding by digesting the skin with strong digestive enzymes, feeding for 3 to 4 days. This feeding causes the intense itching and damage. They then fall off and molt to nonparasitic nymphs and finally adults. Certain pasture areas may become heavily infested with chiggers, which can cause massive infestations resulting in severe dermatitis in horses.

Mite Control

Mange control requires isolation of infested animals and thorough wetting of the whole animal with timed applications of approved pesticides.

Chiggers can be controlled by application of detergent wash containing one of the insecticides registered for other mites. Area control is not feasible.

Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes (Figure 19) are small, two-winged flies with piercing sucking mouthparts. Females of most species suck blood, males do not. Mosquitoes attack all kinds of warm-blooded animals, domestic and wild. Florida has many species recorded as economic pests on livestock.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Although habits of different species vary greatly, all require water for the larval stage. Female mosquitoes lay their eggs on water or in places that later become flooded. Egg hatch varies with the species. Larvae (wigglers) hatch from the eggs and feed on organic matter in the water. Pupation takes place in the water. The adult mosquito emerges and is ready to feed in a short time.

Damage caused by mosquitoes include pain from the bites, unthriftiness, death by suffocation, and heavy blood loss. Mosquitoes also vector such diseases as encephalomyelitis (WNV, WEE, EEE, VEE) and are suspect for many of the mechanically transmitted diseases.

If mosquitoes are a serious problem to horses, control measures should be implemented. The most effective control method available is source reduction by removing or draining mosquito immature developmental sites, through the activity of mosquito control districts. Daily fogging or aerosoling for adult mosquitoes may provide relief but is only a temporary control measure.

Ticks

Two general groups of ticks attack horses, hard ticks and soft ticks. Hard ticks (Figure 20) have long association with the host, feed slowly, take a large blood meal, drop from the host to molt, and lay many eggs. Their mouthparts are anterior and may be seen from above. Ticks are easily distinguished from insects, since the body is not definitely divided and the strong fusion of the thorax and abdomen produces a sac-like leathery appearance. A distinct head is lacking, but there is a head-like structure which bears recurved teeth that are inserted into the wound, allowing the tick to hold on strongly. Females can be greatly distended and are bean-like in form when fully engorged. Ticks have four developmental stages: egg, 6-legged seed or larval stage, 8-legged nymphal stage, and 8-legged adult.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Males, females, and immatures all feed on blood and lymph. A fully engorged female usually deposits eggs (from 100 to 18,000) on the ground. The larval or seed ticks emerging from eggs usually climb up grasses or other low vegetation to contact passing animals. The larvae molt once into nymphs and go through 1 to 5 (soft ticks only) nymphal stages. Ticks remain in the 8-legged form until they emerge as sexually mature adults. The majority drop off the host to molt after feeding.

The effects of ticks upon the host include inflammation, itching and swelling at the bite site, blood loss, production of wounds that may serve as sites for secondary invasion, obstruction of body openings and paralysis from the injection of toxic fluids. They also transmit many diseases, including anaplasmosis, equine piroplasmosis, and tularemia.

The two most common species in Florida include one hard tick, the tropical horse tick, and one soft tick, the spinose ear tick (Figure 21). The tropical horse tick infests the ears as a one host tick and can be found on animals in South Florida. It is a dangerous vector of babesiosis in horses. The spinose ear tick is a soft tick that also infests the ears and feeds only as larvae and second stage nymphs. Both ticks can cause severe damage to the ear and inner ear.

Credit: J. F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Tick control may be attempted through area or premise control with insecticides. Premise control kills ticks which are either engorged or on foliage waiting to contact a host. On animals, control may also be successful with spray or dips.

Keys To Pesticide Safety

-

Before using any pesticide, stop and read the precautions.

-

Read the label on each pesticide container before each use. Heed all warnings and precautions.

-

Store all pesticides in their original containers away from food or feed.

-

Keep pesticides out of the reach of children, pets, and livestock.

-

Apply pesticides only as directed.

-

Dispose of empty containers promptly and safely.

Recommendations in this document are guidelines only. The user must insure that the pesticide is applied in strict compliance with label directions.

The Food and Drug Administration has established residue tolerances for certain insecticides in the meat of certain animals. When these and other approved insecticides are applied according to recommendations, the pests should be effectively controlled and the animals' products will be safe for consumption.

The improper use of insecticides may result in residue in milk or meat. Such products must not be delivered to processing plants. To avoid excessive residues, use the insecticides recommended at the time recommended and in the amounts recommended.

See ENY-272 Pesticide Safety around Animals for information on how to correctly and safely treat livestock with insecticides.

Locating an Approved Pesticide

In 2014, a group of livestock entomologists, as a part of Multistate Hatch Project S-1060, developed an online system for obtaining the names of registered pesticides appropriate for use with livestock and pets. This is a state-specific database (only certain states are represented, and Florida is one of these); if you are in another state, you must be certain that your state is represented in the dropdown list.

This database is easily searchable by the type of animal or site that you want to treat (such as a barn), as well as the targeted pest. From these two selections, you can then choose the "Method of Application" and the "Formulation Type." To use this system, please visit the following website https://www.veterinaryentomology.org/vetpestx.

Although the group continuously strives to keep this database current, it is ultimately your responsibility to ensure that the product that you choose is registered in the state that you plan to make the application and that you use the product in accordance with the label requirements and local laws and ordinances. Remember, "the label is the law" for pesticide use, and the uses indicated on the label, including the site of application and targeted pest(s) must be on the label.

If you have any challenges with this system, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office (https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/find-your-local-office/) or for additional assistance contact Dr. Phillip Kaufman, pkaufman@ufl.edu.

References

Broce, A. B. 1988. "An improved Alsynite trap for stable flies Stomoxys calcitrans (Diptera: Muscidae)." J. Med. Entomol. 25: 406–409.

Catts, E. P. and G. R. Mullen. 2002. Myiasis (Muscoidea, Oestroidea), In: Medical and Veterinary Entomology, (G. R. Mullen and L. A. Durden, Eds.), pp.18–348. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science.

George, J. E., R. B. Davey and J. M. Pound. 2002. "Introduced ticks and tick-borne diseases: the threat and approaches to eradication." Vet. Clin. Food Anim. 18: 401–416.

Hogsette, J. A. and J. P. Ruff. 1985. "Stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae) migration in Northwest Florida." Environ. Entomol. 14: 170–175.

Jones, C. J., J. A. Hogsette, R. S. Patterson, D. E. Milne, G. D. Propp, J. F. Milio, L. G. Rickard and J. P. Ruff. 1991. "Origin of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) on West Florida beaches: Electrophoretic analysis of dispersal." J. Med. Entomol. 28: 787–795.

Knapp, F. W. 1985. Arthropod pests of horses. In: Livestock Entomology (R. E. Williams, R. D. Hall, A. B. Broce and P. J. Scholl, eds.), pp. 297–322. Wiley, New York.

Lysyk, T. J. and R. C. Axtell. 1986. "Movement and distribution of house flies (Diptera: Muscidae) between habitats on two livestock farms." J. Econ. Entomol. 76: 993–998.

Moon, R. D. 2002. Muscoid flies (Muscidae), In: Medical and Veterinary Entomology, (G. R. Mullen and L. A. Durden, Eds.), pp. 45–65. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science.

Mullens, B. A. 2002. Horse flies and deer flies (Tabanidae), In: Medical and Veterinary Entomology, (G. R. Mullen and L. A. Durden, Eds.), pp. 264–278. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science.

Pickens, L. G., E. T. Schmidtmann and R. W. Miller. 1994. How to control house and stable flies without using pesticides, pp. 1–14. Washington, DC: USDA.

Sonenshine, D. E., R. S. Lane and W. L. Nicholson. 2002. Ticks (Ixodida), In: Medical and Veterinary Entomology, (G. R. Mullen and L. A. Durden, Eds.), pp. 518–558. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Science.

Steinkraus, D. C., C. J. Geden and D. A. Rutz. 1993. "Prevalence of Entomophthora muscae (Cohn) Fresenius (Zygomycetes: Entomophthoraceae) in house flies (Diptera: Muscidae) on dairy farms in New York and induction of epizootics." Biol. Cont. 3: 93–100.