Introduction

Myllocerus undecimpustulatus undatus Marshall, the Sri Lankan weevil, is a plant pest with a wide range of hosts. This weevil spread from Sri Lanka into India and then Pakistan where many subspecies of Myllocerus undecimpustulatus Faust are considered pests of more than 20 crops. In the United States, the Sri Lankan weevil was first identified on Citrus sp. in Pompano Beach a city in Broward County Florida. Three specimens were identified by Dr. Charles W. O'Brien, first as Myllocerus undecimpustulatus, a species native to southern India, and then again as Myllocerus undatus Marshall native to Sri Lanka, finally as Myllocerus undecimpustulatus undatus Marshall to show its status as a subspecies.

Credit: Anita Neal, UF/IFAS

Distribution

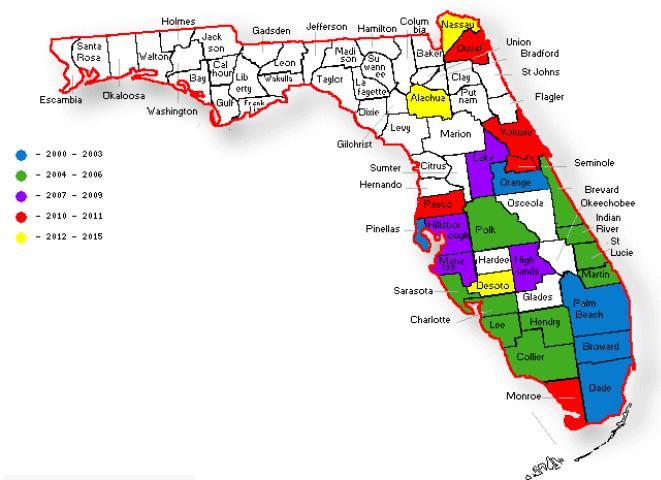

The Sri Lankan weevil was first detected in 2000. By May 2006 it was found in 12 counties in Florida. Michael Thomas of the Florida Division of Plant Industry has obtained data from field agents identifying this weevil in an additional 15 counties since May of 2006. It has not been determined how the Sri Lankan weevil arrived in south Florida.

Credit: Anita Neal, UF/IFAS

Description

Adults

Adult Sri Lankan weevils vary in length from approximately 6.0 to 8.5 mm; the female weevil is slightly larger than the male by 1.0 to 2.0 mm. Some of the notable features of the Sri Lankan weevil are toothed femora (front and middle bidentate and hind femora tridentate), strongly angled humeri (shoulders, see red arrows in Figures 3 and 6) are broader than the prothorax, the yellowish coloration of the head, and the dark-mottled elytra. These features help distinguish the Sri Lankan weevil from other weevils of similar size and coloration. Artipus floridanus Horn, the little leaf notcher, is most similar in appearance but the femora lack teeth, the humeri are not angled, and the elytra are grayish to white, with smaller black cuticular marks formed by perforations on the elytra.

Credit: Anita Neal, UF/IFAS

Credit: Anita Neal, UF/IFAS

Credit: Paul Skelley, FDACS-Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Paul Skelley, FDACS-Division of Plant Industry

Eggs

Female Myllocerus spp. may lay up to 360 eggs over a 24-day period, and larvae emerge in 3–5 days. Sri Lankan weevil eggs are laid directly on organic material at the soil surface, which is common for most Myllocerus spp. Eggs are less than 0.5 mm, ovoid and usually laid in clusters of 3–5. The eggs are white or cream-colored at first, then gradually turn brown when they are close to hatching.

Larvae

The larvae range in size from 1.09 ± 0.05 mm as first instar larvae to 4.0 ± 0.05 mm as fourth instar larvae and are beige-white with a reddish-brown head. They burrow into the soil where they feed on plant roots for approximately one to two months. The larvae pupate in the soil for approximately one week.

Credit: Holly Glenn, University of Florida

Host Plants

The Sri Lankan weevil has a wide host range of over 150 plant species including native, ornamental, vegetable and fruit species. Some host plant examples include Citrus spp., citrus; Conocarpus erectus, green buttonwood; Bauhinia x blakeana, Hong Kong orchid tree; Chrysobalanus icaco, cocoplum; Phoenix roebellenii, pygmy date palm; Prunus persica, peach; Lagerstroemia indica, crepe myrtle; Capsicum spp., pepper; Litchi chinensis, lychee; Muntingia calabura, strawberry tree; and Solanum melongena, eggplant. It is unclear what the larval host plants are, but they have been reared in the laboratory on pepper, eggplant, cotton, carrot, and sweet potato roots.

Credit: Holly Green, University of Florida

Economic Importance

Leaf-feeding adults damage the foliage of ornamental plants, fruit trees, and vegetables, whereas the larvae injure root systems. Due to its feeding habits, the Sri Lankan weevil could negatively affect subtropical and tropical fruit, ornamental, and vegetable industries here in Florida. The possible impact to the horticulture industry in nurseries, landscape services, and horticultural retailers could reach billions of dollars based on the value they generate in Florida (Kachatryan and Hodges 2012). Extension agents and Master Gardener volunteers around the state have received requests from homeowners for information on the control of this weevil. Botanical gardens and plant nurseries have reported damage due to chewing injury and require effective control measures.

Damage

When adult weevils feed on leaves, they feed inward from the leaf margins (or edges), causing the typical leaf notching. There are some instances where the leaf material is almost completely defoliated, where the weevil has fed along the leaf veins. The adults prefer new plant growth. Intense feeding by numerous weevils may cause plant decline or stunting. Young seedlings may not survive a large amount of feeding damage. With healthy plants, however, the feeding damage may be considered cosmetic if the plant recovers.

Credit: Susan Halbert, FDACS—Division of Plant Industry

Management

Traditional methods of control include pesticides, many of which provide only limited management of this pest. Chemical control of the adults is difficult because of their ability to fly, hide, or feign death and drop to the ground. Chemical control of the eggs, larvae, and pupae is more difficult due to their location on or in the soil.

Adult weevils can be removed from plants by vigorously shaking a branch over an open, inverted umbrella. The collected weevils can then be dumped into a container of soapy water.

As insecticide recommendations and regulations are updated yearly, it is advisable to consult your local UF/IFAS Extension office or a pesticide reference guide for current information on control methods for this pest.

Selected References

Arevalo HA, Stansly PA. 2009. Suppression of Myllocerus undatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Valencia orange with chlorpyrifos sprays directed at ground and foliage. Florida Entomologist 92: 150–152.

Atwal AS. 1976. Agricultural pests of India and South-East Asia. New Delhi, India: Kalyani Publishers. pp. 295–296.

Epsky N, Walker A, Kendra PE. 2009. Sampling methods for Myllocerus undecimpustulatus undatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) adults. Florida Entomologist 92: 388–390.

Frank JH, Thomas MC. 2012. Invasive insects (adventive pest insects) in Florida. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. (5 November 2013)

Josephrajkumar A, Rajan P, Mohan C, Thomas RJ. 2010. First record of Asian grey weevil (Myllocerus undatus) on coconut from Kerala, India. Phytoparasitica 39: 63–65.

Khachatryan H, Hodges AW. 2012. Florida nursery crops and landscape industry economic outlook. UF/IFAS, Food and Resource Economics Department, Gainesville. November 2012. 4–5. (23 October 2013)

Mannion C, Hunsberger A, Gabel K, Buss E, Buss L. 2006. Sri Lanka weevil (Myllocerus undatus). UF/IFAS, Tropical Research and Education Center, Homestead. August 2006: pp. 1–2. (23 October 2013)

O'Brien CW, Haseeb M, Thomas MC. 2006. Myllocerus undecimpustulatus undatus Marshall (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), a recent discovered pest weevil from the Indian subcontinent. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Entomology Circular No. 412. (23 October 2013)

Thomas M. 2005. A weevil new to the Western Hemisphere. Pest Alert. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry. (23 October 2013)

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Morgan Conn, Dr. Ron Cave, Dr. John Capinera, and Dr. Howard Frank for their review of this document.