Introduction

The Carolina satyr, Hermeuptychia sosybius (Fabricius, 1793) has a range that spans 13 states across the southeastern US and is often abundant where it occurs. Adults are delicate and fly close to the ground in a slow, bouncy flight pattern that is characteristic of butterflies from the subtribe Euptychiina. Although they may appear rather drab at first glance, the ventral (bottom) surface of both the fore- and hind-wings bear a series of eyespots that are quite striking (Figures 1 and 2).

Credit: Sebastián Padrón, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador

Credit: (Left) Jonathan Bremer, McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, Florda Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. (Right) Denise Tan, University of Florida

Historically, southern populations of Hermeuptychia sosybius have occasionally been classified under the name Hermeuptychia hermes. Morphological and molecular evidence have since provided strong support that the latter name should be reserved for South American specimens (Hermeuptychia hermes was originally described from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and therefore not applied to Hermeuptychia populations in North America.

Synonymy

Hermeuptychia hermes kappeli Anken, 1993

(From: A catalogue of the butterflies of the United States and Canada, Jonathan P. Pelham.)

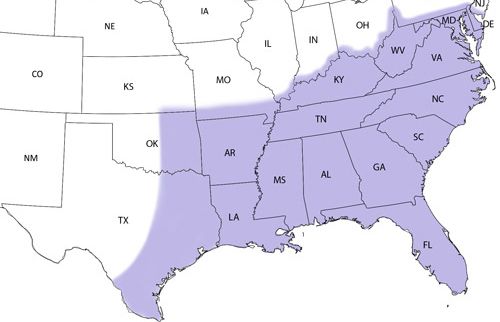

Distribution

The Carolina satyr can be found throughout Florida (excluding the Keys), north along the Atlantic coast to southern New Jersey, and west to southeastern Kansas, central Oklahoma, and central to south Texas (Figure 3).

Credit: Denise Tan, base map from https://freevectormaps.com

These butterflies prefer shaded environments in upland and wetland ecosystems and have been found in a variety of habitats including forest margins, hammocks, flatwoods, margins of swampy areas, grassy openings, and woodlands.

Description

Adults

Adults are relatively small and inconspicuous butterflies. Typical wingspan ranges from 1¼–1½ inches (32–38 mm). The dorsal side of the wings is dull brown without overt markings. The underside of the wings is a lighter brown with two dark transverse lines and two dark dashes. A series of yellow-rimmed eyespots occur along the edge of the wing. There is one prominent eyespot (black with light center) on the forewing and three on the hindwing (Figures 1 and 2).

There is some evidence for seasonal variability in adult morphology. Spring adults tend to be larger with relatively smaller eyespots. In contrast, summer adults usually have a smaller body with relatively larger eyespots (Warren et al. 2014a).

Eggs

Pale green eggs are laid singly on the leaves of grasses (Figure 5a). The dark head capsule of the developing larva becomes apparent within the semi-transparent egg case a few days prior to eclosion (Figure 4).

Credit: Dan Tan, University of Florida

Larvae

Caterpillars develop through four instars (developmental stages) before pupation and attach themselves on the underside of leaves using loosely woven silk pads.

Newly emerged larvae have a round, black head capsule without obvious horns or projections but with elongated setae (stiff hairs). Larval bodies are white (Figure 4) and acquire the deeper green coloration of the host grass after active feeding (Figure 5b). Several longitudinal white stripes run the length of the body and elongated white setae are found on each segment (Figure 5c, d).

In the second instar, the black head capsule is replaced with a light green head capsule bearing many small white protuberances (Figure 5e). The body is light green with short white setae and several white longitudinal stripes. A pair of short caudal filaments is present (Figure 5f, g).

Third instar larvae look very similar to the previous instar, except with larger head capsules and longer bodies (Figure 5i, j).

White dorsolateral spots are present on the bodies of fourth instar larvae and the longitudinal stripes become less conspicuous (Figure 5k, l).

Pupae

Recently pupated insects appear bright green and are extremely well camouflaged. The pupal case is smooth. A reddish-brown stripe and a series of black dots are visible on the margins of the wing caps (Figure 5n, o). The pupae darken just prior to eclosion, and the fully formed adult becomes visible through the semi-transparent pupal case (Figure 5p).

Credit: Reproduced with permission from corresponding author, Nick V. Grishin, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Cong and Grishin 2014)

Similar Species

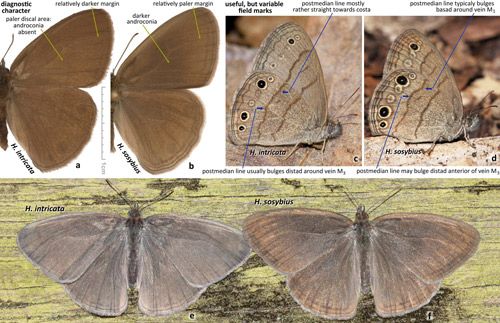

Intricate Satyr (Hermeuptychia intricata)

The Carolina satyr (Hermeuptychia sosybius) can easily be confused with the intricate satyr (Hermeuptychia intricata Grishin) as both species are found in the same geographic areas and display extreme similarity of wing pattern and flight behavior (Figure 6c–d).

In the field, Carolina satyr males can be distinguished by the presence of a dense patch of dark androconial scales (specialized scales commonly associated with pheromone dissemination) on the dorsal surface of most of the forewing and part of the hindwing. Male intricate satyrs lack this two-toned appearance on their wings and appear more uniformly colored (Figure 6a–b, e–f).

Unfortunately, this sexually dimorphic character is not present in Carolina satyr females, making field identifications of female specimens particularly tricky.

Credit: Reproduced with permission from Nick V. Grishin, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Warren et al. 2014b)

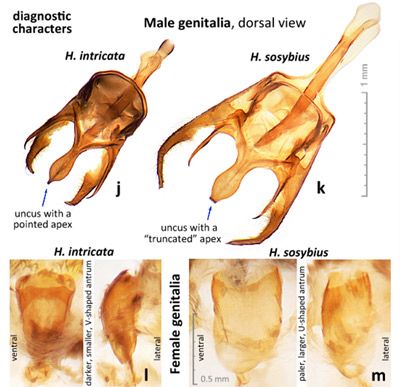

These cryptic species are genetically distinct (3.5% difference in the barcoding gene, cytochrome oxidase I) and demonstrate clear differences in genital morphology. Specifically, the apex of the uncus in Carolina satyr males is wider and truncated. In females, the antrum is paler, larger and has a rounder U shape (as opposed to the sharper V shape in intricate satyr females) (Figure 7).

Credit: Reproduced with permission from Nick V. Grishin, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Warren et al. 2014b)

Life Cycle

In the northern part of the Carolina satyr's range, adults are active only in the warmer months of April to October and they produce three generations each year. It is not currently known if they overwinter as eggs or larvae. In Florida, higher annual temperatures allow Carolina satyrs to be active year-round, and they produce more than three broods annually. Males are commonly encountered patrolling during the day, in search of potential mates.

Credit: Denise Tan, University of Florida

Hosts

Adults feed on tree sap and rotting fruit.

Larvae of the Carolina satyr feed on grasses of the family Poaceae, including:

-

Common carpetgrass (Axonopus fissifolius)

-

St. Augustinegrass (Stenotaphrum secundatum)

-

Basketgrass (Oplismenus hirtellus)

-

Tropical signalgrass (Urochloa distachya)

-

Orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata)

-

Centipedegrass (Eremochloa ophiuroides)

-

Guineagrass (Megathyrsus maximus)

Caterpillars reared in captivity have also readily accepted Bermudagrass (Cynodon sp.) (Cong and Grishin 2014, Dole et al. 2004, Minno et al. 2005, Opler and Malikul 1998).

Conservation Status

This species is not endangered, but neither is it as common or widespread as it was once thought to be since genetic studies (Cong and Grishin 2014) have revealed the existence of multiple similar-looking species rather than a single common one. Such discoveries affect estimates of biodiversity and endemism and consequently, conservation prioritization and management as well.

Selected References

Cong Q, Grishin NV. 2014. A new Hermeuptychia (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Satyrinae) is sympatric and synchronic with H. sosybius in southeast US coastal plains, while another new Hermeuptychia species–not hermes–inhabits south Texas and northeast Mexico. ZooKeys 379: 43–91.

Dole JM, Gerard WB, Nelson JM. 2004. Butterflies of Oklahoma, Kansas, and North Texas. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma. 98 pp.

Glassberg J. 2004. Butterflies of North America. Barnes and Noble Publishing, New York. 168 pp.

Lotts K, Naberhaus T. 2015. Butterflies and Moths of North America. http://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/species/Hermeuptychia-sosybius (26 May 2016)

Minno MC, Butler JF, Hall DW. 2005. Florida butterfly caterpillars and their host plants. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, Florida. 119 pp.

Opler PA, Malikul V. 1998. A Field Guide to Eastern Butterflies. Peterson Field Guides. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, New York. 300 pp.

Seraphim N, Marín MA, Freitas AVL, Silva-Brandão KL. 2014. Morphological and molecular marker contributions to disentangling the cryptic Hermeuptychia hermes species complex (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae: Euptychiina). Molecular Ecology Resources 14: 39–49.

Wagner DL. 2005. Caterpillars of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. 136 pp.

Warren AD, Davis KJ, Grishin NV, Pelham JP, Stangeland EM. 2012. Interactive Listing of American Butterflies. http://www.butterfliesofamerica.com/hermeuptychia_sosybius.htm (26 May 2016)

Warren AD, Willmott KR, Grishin NV. 2014a. Subtle satyrs: Differentiation and distribution of the newly described Hermeuptychia intricata in the Southeastern United States (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Satyrinae). News of The Lepidopterists' Society 56: 83–85.

Warren AD, Tan D, Willmott KR, Grishin NV. 2014b. Refining the diagnostic characters and distribution of Hermeuptychia intricata (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae: Satyrini). Tropical Lepidoptera Research 24: 44–51.