Introduction

The forked fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus (Panzer), is a cryptic horned beetle in the family Tenebrionidae that is found throughout much of eastern North America. The most distinctive feature of the forked fungus beetle is a pair of forward-facing horns that emerge from the thorax of the adult male (Figure 1). Males use these horns in competitions with rivals for access to reproductive opportunities with females. These beetles spend most of their lives on or within shelf fungi that grow on decaying logs.

Credit: James C. Dunford, US Navy

The fascinating life history of the forked fungus beetle makes this insect an excellent model for studying behavior, population dynamics, and sexual selection.

Distribution

The forked fungus beetle is widespread across most of eastern North America, including New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Florida (Dunford et al. 2005), extending into eastern Canada (Liles 1956; Pace 1967).

Description

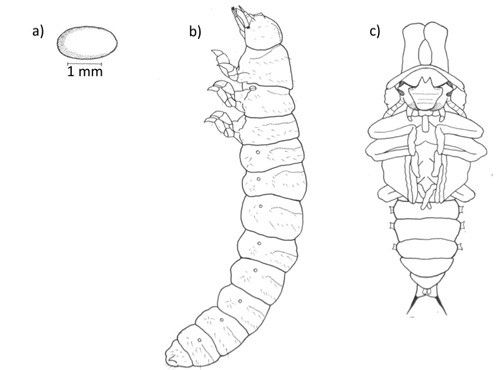

Eggs

The female lays a single egg on the fruiting body of its fungal host and produces a dark secretion to cover the eggs. The function of this secretion has not been determined, however it likely serves to protect the egg from predators (Pace 1967).

Larvae

Larvae are white and cylindrical, with distinct segmentation (Figure 2), and are covered with fine transparent hairs. The head capsule is darker than the body, globular in shape, and bears forward-facing mouthparts (Peterson 1951).

Credit: Stan Malcolm, www.stanmalcolmphoto.com

Pupae

Pupae are pale yellow and are found within fungal bodies. On average, males are 16.5 mm in length and females are 14.6 mm. Male pupae possess two slightly curved thoracic projections (Figure 3c) that correspond to the developing horns of adults (Peterson 1951).

Credit: Modified from Liles (1956)

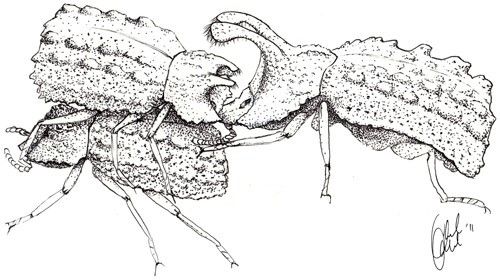

Adults

Adults range from 10.0–12.0 mm in length and 3.5–4.0 mm in width. They range in color from dull black to brown. Males and females have similarly elongate bodies that are rectangular in cross section. Antennae have ten segments. The pronotum (dorsal portion between the head and abdomen) is roughly sculptured with a variable number of rounded teeth. The forewing (elytral) surface is also roughly sculptured with rows of large and small, irregular tubercles (small, rounded projections). The ventral surface of the body is dull black and lusterless, and males have a patch of setae on the inner face of the femora (the third, and broadest, segment on the leg). Males have distinct horns that project forward from the pronotum, ending in an expanded, brush-like tip (Figure 4). The ventral surface of the horn is covered by an obvious patch of dense yellow setae. In addition to these large horns on the pronotum, males possess a pair of smaller horns projecting from the front of the head. Females lack horns but have two small, distinct tubercles on the pronotum (Figure 7) (Triplehorn 1952).

Credit: Stan Malcolm, www.stanmalcolmphoto.com

Life Cycle

Eggs are most often laid singly on the surface of fungus brackets and hatch, on average, 16 days later. The larva burrows into the fungus and undergoes four instars under laboratory conditions (Pace 1967). In natural conditions, however, apparent fifth instar larvae may also occur (Liles 1956). The first through fourth instar larvae develop within excavated tunnels in the fungus. Larvae often overwinter within the fungal tissue and emerge as adults the following summer. However, adults can sometimes emerge in late summer and overwinter within the fungus or under bark. Adult females lay eggs in the summer months, and larvae hatch and undergo development until retarded by cool winter conditions. Adults can live up to eight years (Formica et al. 2010), and may remain on fungal bracts growing on the same tree for many of these years (Pace 1967).

Hosts

The forked fungus beetle feeds mainly on tissues and spores of the fruiting bodies of polyporoid shelf fungi including Ganoderma applanatum, Ganoderma tsugae, and Fomes fomentarius (most of the fungal mycelium is contained within the trees) (Liles 1956, Pace 1967).

Credit: Stan Malcolm, www.stanmalcolmphoto.com

Defense

Adult forked fungus beetles are protected by a thick, sculptured exoskeleton. Adults perform two distinct defensive behaviors: when threatened by mechanical stimuli, such as poking or prodding, beetles perform a death feint (Liles 1956; Pace 1967) and when exposed to mammalian breath, adults raise the abdomen, exposing the abdominal glands, which secrete irritating chemicals (Conner et al. 1985). One researcher described the effect of these chemicals: "The substance has pungent odor. It burns when it touches the inside of the mouth and is bitter tasting and nauseating" (Pace 1967).

Credit: Stan Malcolm, www.stanmalcolmphoto.com

The composition of the defensive volatiles in abdominal secretions differs depending on the species of host fungus on which the beetle feeds. In one study beetles collected from two different species of fungus differed significantly in the relative amount of the chemical benzoquinone in their secretions (Holliday et al. 2009).

Sexual Selection

Adult forked fungus beetles spend daylight hours under tree bark or within the fungus bracket itself, while feeding and mating occur on the surface of the fungus bracket, mostly at night (Liles 1956; Pace 1967). A male courts a female by climbing onto her back and orienting himself so that his head faces in the opposite direction of the female's head (Figure 8). Courtship lasts between ten minutes and several hours, after which the male often attempts to mate (Conner 1988). Females can reject or accept a male attempting copulation by raising (or not raising) a plate at the tip of the abdomen (anal sternite) (Benowitz et al. 2012). After copulation, males often prevent other males from subsequent matings with a female by guarding or remaining on top of her for two to five hours (Conner 1988). Mating, courtship, and competition occur on an observable arena (the surface of a fungus bracket), providing an opportunity to record detailed social interactions among individuals. Wild populations of these beetles have been used to study social networks and sexual selection (Formica et al. 2010).

Credit: Stan Malcolm, www.stanmalcolmphoto.com

Males are often found defending fungal brackets and have been observed chasing away rival males. However, most aggressive encounters between males occur during courtship and copulation (Pace 1967). Males can use one or both pairs of horns to pry courting or copulating males off of a female, like a wedge and a bottle opener, respectively (Benowitz et al. 2012).

Video 1

Video of male competition in Bolitotherus cornutus (Panzer). Video from supporting material, Benowitz et al. 2012.

Credit: Ariel Kahrl, reproduced from Benowitz et al. 2012

Experimental evidence suggests horn length does not influence male access to breeding sites or food, but it does significantly increase mating success. This result suggests that the relative size of a male's horns is important in achieving access to mates, but not necessarily important in defending the fungal resource (Brown and Bartalon 1986; Brown and Siegfried 1983).

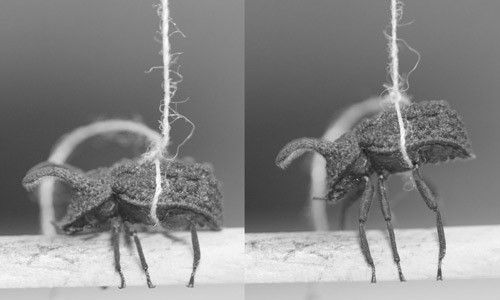

Body size and grip strength are also likely to be important to mating success, as males that resist being displaced from the females during copulation are more likely to reproduce. Experimental tests of grip strength measured the force required to dislodge the beetle from a standardized substrate (Figure 9). The results of these experiments show that grip is stronger in larger individuals and differs between males and females, suggesting that these traits may be also under sexual selection (Benowitz et al. 2012).

Credit: Benowitz et al. 2012

One study conducted on a single population over three years found that males with larger bodies, and specifically larger horns, achieved the highest mating success. Horn length appears to confer an advantage to mating success in low-density populations, but not necessarily in high-density populations. Male age can also be an important determinant of mating success, with older males mating more than younger males (Conner 1988, 1989a, 1989b).

Population Structure

The population distribution of the forked fungus beetle is closely related to the presence of decaying logs harboring their host fungus brackets. The cyclical nature of fungal resource emergence and exploitation by beetles ensures that well-established populations and newly emerging populations co-occur on a landscape scale. The patchy nature of these populations makes this system an excellent model for investigating the effects of local extinction and re-colonization (Whitlock 1991; Wood et al. 2013). As a result, the presence of this beetle has been used to infer the effect of habitat fragmentation at different scales (Kehler and Bondrup-Nielsen 1999).

Selected References

Benowitz KM, Brodie ED, Formica VA. 2012. Morphological correlates of a combat performance trait in the forked fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus. PloS one 7: 1–5.

Brown L, Bartalon J. 1986. Behavioral correlates of male morphology in a horned beetle. The American Naturalist 127: 565–570.

Brown L, Siegfried, BD. 1983. Effects of male horn size on courtship activity in the forked fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 76: 253–255.

Conner J. 1988. Field measurements of natural and sexual selection in the fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus. Evolution 42: 736–749.

Conner J. 1989a. Density-dependent sexual selection in the fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus. Evolution 43: 1378–1386.

Conner J. 1989b. Older males have higher insemination success in a beetle. Animal Behavior 38: 503–509.

Conner J, Camazine S, Aneshansley D, Eisner T. 1985. Mammalian breath: Trigger of defensive chemical response in a tenebrionid beetle (Bolitotherus cornutus). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 16: 115–118.

Dunford JC, Thomas MT, Choate Jr. PM. 2005. The darkling beetles of Florida and the eastern United States (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). (11 December 2017)

Formica VA, Augat ME, Barnard ME, Butterfield, RE, Wood CW, Brodie, ED. 2010. Using home range estimates to construct social networks for species with indirect behavioral interactions. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 64: 1199–1208.

Holliday AE, Walker FM, Brodie ED, Formica, VA. 2009. Differences in defensive volatiles of the forked fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus, living on two species of fungus. Journal of Chemical Ecology 35: 1302–1308.

Kehler D, Bondrup-Nielsen S. 1999. Effects of isolation on the occurrence of a fungivorous forest beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus, at different spatial scales in fragmented and continuous forests. Oikos 84: 35–43.

Liles MP. 1956. A study of the life history of the forked fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus (Panzer) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Ohio Journal of Science 56: 329–337.

Pace AE. 1967. Life history and behavior of a fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus (Tenebrionidae). Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 653: 1–16.

Peterson A. 1951. Larvae of insects. Part II. Coleoptera, Diptera, Neuroptera, Siphonaptera, Mecoptera, Trichoptera. Edwards Bros. Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Triplehorn CA. 1952. Tenebrionidae of Ohio. MSc. Thesis, The Ohio State University. Columbus.

Whitlock MC. 1991. Nonequilibrium population structure in forked fungus beetles: Extinction, colonization and the genetic variance among populations. The American Naturalist 139: 952–970.

Wood CW, Donald HM, Formica VA, Brodie ED. 2013. Surprisingly little population genetic structure in a fungus-associated beetle despite its exploitation of multiple hosts. Ecology and Evolution 3: 1484–1494.