The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Maevia inclemens is a common jumping spider (Family Salticidae) distributed throughout eastern North America, primarily found along tree lines in vines and ivy (Bradley 2012). Like most jumping spiders, Maevia inclemens is a voracious generalist predator that feeds on a variety of small insects and other arthropods. Curiously, Maevia inclemens is the only known jumping spider (from a family of nearly 6,000 species) (World Spider Catalog 2017) to have dimorphic males; these two types of males (or morphs) differ in both morphology and courtship behavior and are found in roughly equal frequency in a population (Clark and Uetz 1990).

Credit: Laurel Lietzenmayer, UF/IFAS

Description

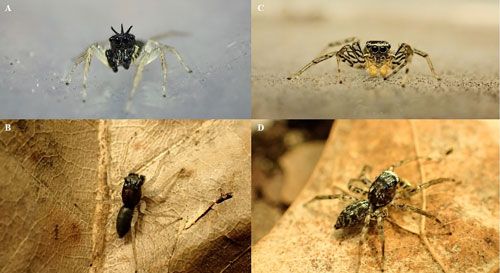

Maevia inclemens is a medium-sized jumping spider with females larger than males. Females are 6.5–10.0 mm (~1/4–3/8 in) and males are 4.8–7.0 mm (~3/16–¼ in) in total body length (Bradley 2012). Females have a white face and two red or black lines down the back of their abdomens (Bradley 2012, Figure 2). The tufted morph is characterized by three tufts of hair that protrude from their head, with a black body, and white legs (Figure 3A–B). The striped morph (known commonly as the gray morph) has yellow pedipalps (small appendages near their face), black-and-white striped legs, and a gray abdomen with subtle orange markings (Clark and Uetz 1993; Clark and Morjan 2001, Figure 1, 3C–D). It is currently unknown what factors determine which morph a male will become, and it is difficult to predict what morph a juvenile spider will become as an adult.

Credit: Laurel Lietzenmayer, UF/IFAS

Credit: Laurel Lietzenmayer, UF/IFAS

Distribution and Habitat

Maevia inclemens is native to eastern and midwestern North America (Bradley 2012). They are common along bike and hiking trails where they are found on vines and ivy (Figure 4). They are often found specifically on poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) and wintercreeper (Euonymus fortunei) (L. Lietzenmayer and Z. Burns, unpublished data). Both male morphs have been found within the same microhabitat in equal frequencies (Clark and Uetz 1992).

Credit: Laurel Lietzenmayer, UF/IFAS

Courtship

In addition to differences in morphology, the two morphs of Maevia inclemens have different courtship displays. Tufted males court from afar and stand as tall as possible while waving their abdomen from side to side. Striped males approach females at a closer distance and crouch down while moving back and forth (Clark and Uetz 1993; Clark 1994). Females show similar receptivity behaviors to both morphs when courted, including approaching the male, settling near the male, tapping their first leg pair rapidly, and tipping their abdomen from side to side (Clark 1994). Females do not appear to prefer one morph over the other (Clark and Uetz 1990; Clark and Uetz 1993; Clark and Morjan 2001; Clark and Biesiadecki 2002), but it has been shown that females prefer larger tufted males (compared to smaller tufted males) and smaller striped males (compared to larger striped males) (Busso and Rabosky 2016). Females are larger than males and have been observed attacking and eating (cannibalizing) courting males of both morphs, both before and after the male has mated with the female (Clark and Biesiadecki 2002; L. Lietzenmayer unpublished data).

Predators and Prey

Typical predators of Maevia inclemens, in addition to larger conspecifics (spiders of the same species), include large wandering spiders like the dotted wolf spider Rabidosa punctulata (L. Lietzenmayer field observation) or large ants like Formica subsericea (L. Lietzenmayer field observation, Figure 5). Larger jumping spiders are potential predators, especially those in the genus Phidippus.

Credit: Laurel Lietzenmayer, UF/IFAS

Economic Importance

Jumping spiders are mainly carnivorous, feeding on a wide variety of insect prey; as such, they are generally considered beneficial. Many studies have shown that spiders can effectively reduce the densities of pest insects in agroecosystems (Maloney et al. 2003). There is evidence that jumping spiders periodically feed on nectar sources from flowers (Nyffeler et al. 2016). In some instances, this can be beneficial to the plants by enhancing seed production (Ruhren and Handel 1999). Although there are currently no studies specifically on the behavior of Maevia inclemens in agricultural fields, they are most likely similar to other jumping spider species in their feeding habits.

Selected References

Bradley RA. 2012. Common Spiders of North America. University of California Press.

Busso JP, Rabosky ARD. 2016. "Disruptive selection on male reproductive polymorphism in a jumping spider, Maevia inclemens." Animal Behaviour 120: 1–10.

Clark DL. 1994. "Sequence analysis of courtship behavior in the dimorphic jumping spider, Maevia inclemens (Araneae, Salticidae)." Journal of Arachnology 22: 94–107.

Clark DL, Biesiadecki B. 2002. "Mating success and alternative reproductive strategies of the dimorphic jumping spider, Maevia inclemens (Araneae, Salticidae)." Journal of Arachnology 30: 511–518.

Clark DL, Morjan CL. 2001. "Attracting female attention: the evolution of dimorphic courtship displays in the jumping spider Maevia inclemens (Araneae: Salticidae)." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 268: 2461–2465.

Clark DL, Uetz GW. 1990. "Video image recognition by the jumping spider Maevia inclemens (Araneae: Salticidae)." Animal Behaviour 40: 884–890.

Clark DL, Uetz GW. 1992. "Morph-independent mate selection in a dimorphic jumping spider: demonstration of movement bias in female choice using video-controlled courtship behaviour." Animal Behaviour 43: 247–254.

Clark DL, Uetz GW. 1993. "Signal efficacy and the evolution of male dimorphism in the jumping spider Maevia inclemens." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 90: 11954-11957.

Maloney D, Drummond FA, Alford R. 2003. "Spider predation in agroecosystems: can spiders effectively control pest populations?" Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station, University of Maine, Technical Bulletin No. 190.

Nyffeler M, Olson EJ, Symondson WO. 2016. "Plant-eating by spiders." Journal of Arachnology 44: 15–27.

Ruhren S, Handel S. 1999. "Jumping spiders (Salticidae) enhance the seed production of a plant with extrafloral nectaries." Oecologia 119: 227–230.

World Spider Catalog (2017). World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, http://wsc.nmbe.ch, version 18.5 (accessed August 2017).